Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand Newton’s third law of motion.

- Apply Newton’s third law to define systems and solve problems of motion.

There is a passage in the musical Man of la Mancha that relates to Newton’s third law of motion. Sancho, in describing a fight with his wife to Don Quixote, says, “Of course I hit her back, Your Grace, but she’s a lot harder than me and you know what they say, ‘Whether the stone hits the pitcher or the pitcher hits the stone, it’s going to be bad for the pitcher.’” This is exactly what happens whenever one body exerts a force on another—the first also experiences a force (equal in magnitude and opposite in direction). Numerous common experiences, such as stubbing a toe or throwing a ball, confirm this. It is precisely stated in Newton’s third law of motion.

Newton’s Third Law of Motion

Whenever one body exerts a force on a second body, the first body experiences a force that is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to the force that it exerts.

This law represents a certain symmetry in nature: Forces always occur in pairs, and one body cannot exert a force on another without experiencing a force itself. We sometimes refer to this law loosely as “action-reaction,” where the force exerted is the action and the force experienced as a consequence is the reaction. Newton’s third law has practical uses in analyzing the origin of forces and understanding which forces are external to a system.

We can readily see Newton’s third law at work by taking a look at how people move about. Consider a swimmer pushing off from the side of a pool, as illustrated in Figure 1. She pushes against the pool wall with her feet and accelerates in the direction opposite to that of her push. The wall has exerted an equal and opposite force back on the swimmer. You might think that two equal and opposite forces would cancel, but they do not because they act on different systems. In this case, there are two systems that we could investigate: the swimmer or the wall. If we select the swimmer to be the system of interest, as in the figure, then Fwall on feet is an external force on this system and affects its motion. The swimmer moves in the direction of Fwall on feet. In contrast, the force Ffeet on wall acts on the wall and not on our system of interest. Thus Ffeet on wall does not directly affect the motion of the system and does not cancel Fwall on feet. Note that the swimmer pushes in the direction opposite to that in which she wishes to move. The reaction to her push is thus in the desired direction.

Figure 1. When the swimmer exerts a force Ffeet on wall on the wall, she accelerates in the direction opposite to that of her push. This means the net external force on her is in the direction opposite to Ffeet on wall. This opposition occurs because, in accordance with Newton’s third law of motion, the wall exerts a force Fwall on feet on her, equal in magnitude but in the direction opposite to the one she exerts on it. The line around the swimmer indicates the system of interest. Note that Ffeet on wall does not act on this system (the swimmer) and, thus, does not cancel Fwall on feet. Thus the free-body diagram shows only Fwall on feet, w, the gravitational force, and BF, the buoyant force of the water supporting the swimmer’s weight. The vertical forces w and BF cancel since there is no vertical motion.

Other examples of Newton’s third law are easy to find. As a professor paces in front of a whiteboard, she exerts a force backward on the floor. The floor exerts a reaction force forward on the professor that causes her to accelerate forward. Similarly, a car accelerates because the ground pushes forward on the drive wheels in reaction to the drive wheels pushing backward on the ground. You can see evidence of the wheels pushing backward when tires spin on a gravel road and throw rocks backward. In another example, rockets move forward by expelling gas backward at high velocity. This means the rocket exerts a large backward force on the gas in the rocket combustion chamber, and the gas therefore exerts a large reaction force forward on the rocket. This reaction force is called thrust. It is a common misconception that rockets propel themselves by pushing on the ground or on the air behind them. They actually work better in a vacuum, where they can more readily expel the exhaust gases. Helicopters similarly create lift by pushing air down, thereby experiencing an upward reaction force. Birds and airplanes also fly by exerting force on air in a direction opposite to that of whatever force they need. For example, the wings of a bird force air downward and backward in order to get lift and move forward. An octopus propels itself in the water by ejecting water through a funnel from its body, similar to a jet ski. In a situation similar to Sancho’s, professional cage fighters experience reaction forces when they punch, sometimes breaking their hand by hitting an opponent’s body.

Example 1. Getting Up To Speed: Choosing the Correct System

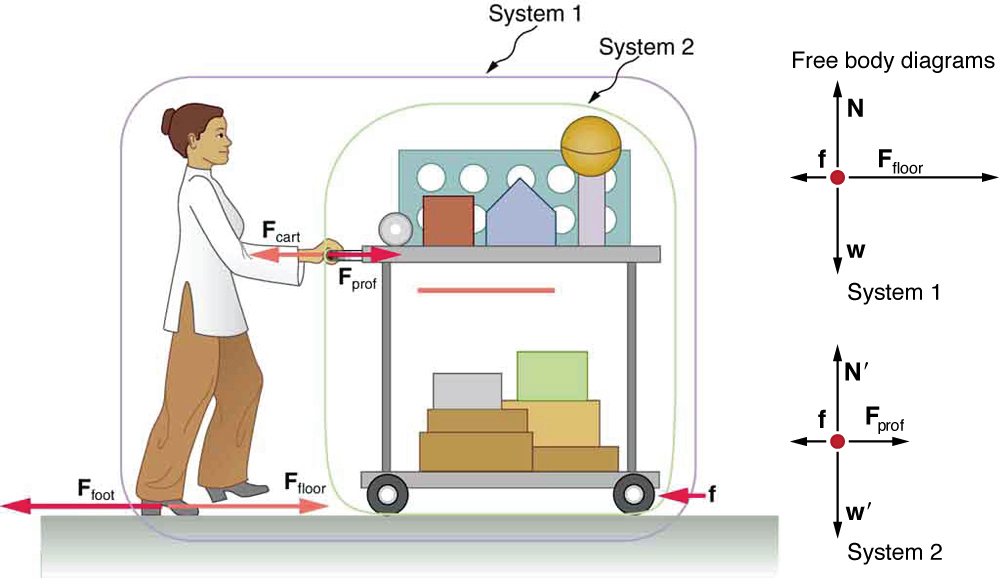

A physics professor pushes a cart of demonstration equipment to a lecture hall, as seen in Figure 2. Her mass is 65.0 kg, the cart’s is 12.0 kg, and the equipment’s is 7.0 kg. Calculate the acceleration produced when the professor exerts a backward force of 150 N on the floor. All forces opposing the motion, such as friction on the cart’s wheels and air resistance, total 24.0 N.

Figure 2. A professor pushes a cart of demonstration equipment. The lengths of the arrows are proportional to the magnitudes of the forces (except for f, since it is too small to draw to scale). Different questions are asked in each example; thus, the system of interest must be defined differently for each. System 1 is appropriate for Example 4.4, since it asks for the acceleration of the entire group of objects. Only Ffloor and f are external forces acting on System 1 along the line of motion. All other forces either cancel or act on the outside world. System 2 is chosen for this example so that Fprof will be an external force and enter into Newton’s second law. Note that the free-body diagrams, which allow us to apply Newton’s second law, vary with the system chosen.

Strategy

Since they accelerate as a unit, we define the system to be the professor, cart, and equipment. This is System 1 in Figure 2. The professor pushes backward with a force Ffoot of 150 N. According to Newton’s third law, the floor exerts a forward reaction force Ffloor of 150 N on System 1. Because all motion is horizontal, we can assume there is no net force in the vertical direction. The problem is therefore one-dimensional along the horizontal direction. As noted, f opposes the motion and is thus in the opposite direction of Ffloor. Note that we do not include the forces Fprof or Fcart because these are internal forces, and we do not include Ffoot because it acts on the floor, not on the system. There are no other significant forces acting on System 1. If the net external force can be found from all this information, we can use Newton’s second law to find the acceleration as requested. See the free-body diagram in the figure.

Solution

Newton’s second law is given by [latex]a=\frac{{F}_{\text{net}}}{m}[/latex].

The net external force on System 1 is deduced from Figure 2 and the discussion above to be

The mass of System 1 is

m = (65.0 + 12.0 + 7.0) kg = 84 kg

These values of F net and m produce an acceleration of

[latex]a=\frac{{F}_{\text{net}}}{m}[/latex]

[latex]a=\frac{126 \text{ N}}{84\text{ kg}}=1.5 \text{ m/s}^{2}[/latex]

Discussion

None of the forces between components of System 1, such as between the professor’s hands and the cart, contribute to the net external force because they are internal to System 1. Another way to look at this is to note that forces between components of a system cancel because they are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. For example, the force exerted by the professor on the cart results in an equal and opposite force back on her. In this case both forces act on the same system and, therefore, cancel. Thus internal forces (between components of a system) cancel. Choosing System 1 was crucial to solving this problem.

Example 2. Force on the Cart—Choosing a New System

Calculate the force the professor exerts on the cart in Figure 2 using data from the previous example if needed.

Strategy

If we now define the system of interest to be the cart plus equipment (System 2 in Figure 2), then the net external force on System 2 is the force the professor exerts on the cart minus friction. The force she exerts on the cart, Fprof, is an external force acting on System 2. Fprof was internal to System 1, but it is external to System 2 and will enter Newton’s second law for System 2.

Solution

Newton’s second law can be used to find Fprof. Starting with

and noting that the magnitude of the net external force on System 2 is

we solve for Fprof, the desired quantity:

The value of f is given, so we must calculate net Fnet. That can be done since both the acceleration and mass of System 2 are known. Using Newton’s second law we see that

[latex]a=\frac{{F}_{\text{net}}}{m}[/latex]

where the mass of System 2 is 19.0 kg (m= 12.0 kg + 7.0 kg) and its acceleration was found to be a = 1.5 m/s2 in the previous example. Thus,

[latex]a=\frac{{F}_{\text{net}}}{m}[/latex]

Fnet = (19.0 kg)(1.5 m/s2) = 29 N

Now we can find the desired force:

Discussion

It is interesting that this force is significantly less than the 150-N force the professor exerted backward on the floor. Not all of that 150-N force is transmitted to the cart; some of it accelerates the professor. The choice of a system is an important analytical step both in solving problems and in thoroughly understanding the physics of the situation (which is not necessarily the same thing).

Conceptual Questions

1. When you take off in a jet aircraft, there is a sensation of being pushed back into the seat. Explain why you move backward in the seat—is there really a force backward on you? (The same reasoning explains whiplash injuries, in which the head is apparently thrown backward.)

2. A device used since the 1940s to measure the kick or recoil of the body due to heart beats is the “ballistocardiograph.” What physics principle(s) are involved here to measure the force of cardiac contraction? How might we construct such a device?

3. Describe a situation in which one system exerts a force on another and, as a consequence, experiences a force that is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. Which of Newton’s laws of motion apply?

4. Why does an ordinary rifle recoil (kick backward) when fired? The barrel of a recoilless rifle is open at both ends. Describe how Newton’s third law applies when one is fired. Can you safely stand close behind one when it is fired?

5. An American football lineman reasons that it is senseless to try to out-push the opposing player, since no matter how hard he pushes he will experience an equal and opposite force from the other player. Use Newton’s laws and draw a free-body diagram of an appropriate system to explain how he can still out-push the opposition if he is strong enough.

6. Newton’s third law of motion tells us that forces always occur in pairs of equal and opposite magnitude. Explain how the choice of the “system of interest” affects whether one such pair of forces cancels.

Problems & Exercises

1. What net external force is exerted on a 1100-kg artillery shell fired from a battleship if the shell is accelerated at 2.40 × 104 m/s2? What is the magnitude of the force exerted on the ship by the artillery shell?

Glossary

- Newton’s third law of motion:

- whenever one body exerts a force on a second body, the first body experiences a force that is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to the force that the first body exerts

- thrust:

- a reaction force that pushes a body forward in response to a backward force; rockets, airplanes, and cars are pushed forward by a thrust reaction force

Selected Solutions to Problems & Exercises

1. Force on shell: 2.64 × 107 N, Force exerted on ship = -2.64 × 107 N, by Newton’s third law

Candela Citations

- College Physics. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/031da8d3-b525-429c-80cf-6c8ed997733a/College_Physics. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Located at License

- PhET Interactive Simulations . Provided by: University of Colorado Boulder . Located at: http://phet.colorado.edu. License: CC BY: Attribution