As the fall of 1860 approached, a four-way race for the Presidency—and the future of America—emerged. The ghost of John Brown, the militant abolitionist hung after his actions at Harper’s Ferry, loomed large in early 1860. In April, the Democratic Party convened in Charleston, South Carolina, acknowledged bastion of secessionist thought in the South. The goal was to nominate a single candidate for the party ticket, but it became very clear that the Democratic convention would be one marked by hostility and division. The northern and southern wings of the party could not agree on any one man. Northern Democrats pulled for Senator Stephen Douglas, a pro-slavery moderate championing popular sovereignty, while Southern Democrats were intent on endorsing someone other than Douglas. The failure to include a pro-slavery platform resulted in Southern delegates walking out of the convention, preventing Douglas from gaining the two-thirds majority required for a nomination. A subsequent convention in Baltimore nominated Douglas for the Democratic ticket, while southerners nominated current Vice President John C. Breckenridge of Kentucky as their presidential candidate. The nation’s oldest party had split into two over differences in policy toward slavery.

Certainly, few Americans expected a strong showing from the Republican Party. Indeed, the Republicans were hardly unified themselves. The leading men of the party all vied for their party’s nomination at the Chicago convention in May 1860. There was a growing recognition among the conveners that the party’s nominee would need to be someone who would be able to carry all the free states—only in that situation could a Republican nominee potentially win. Such an electoral reality meant that the early favorite, New York Senator William Seward, came under attack during the convention. Some believed his pro-immigrant position would prevent him from carrying Pennsylvania and New Jersey in a general election. Abraham Lincoln, as a relatively unknown but likable politician, rose from a pool of potential candidates, and was selected by the delegates on the third ballot.

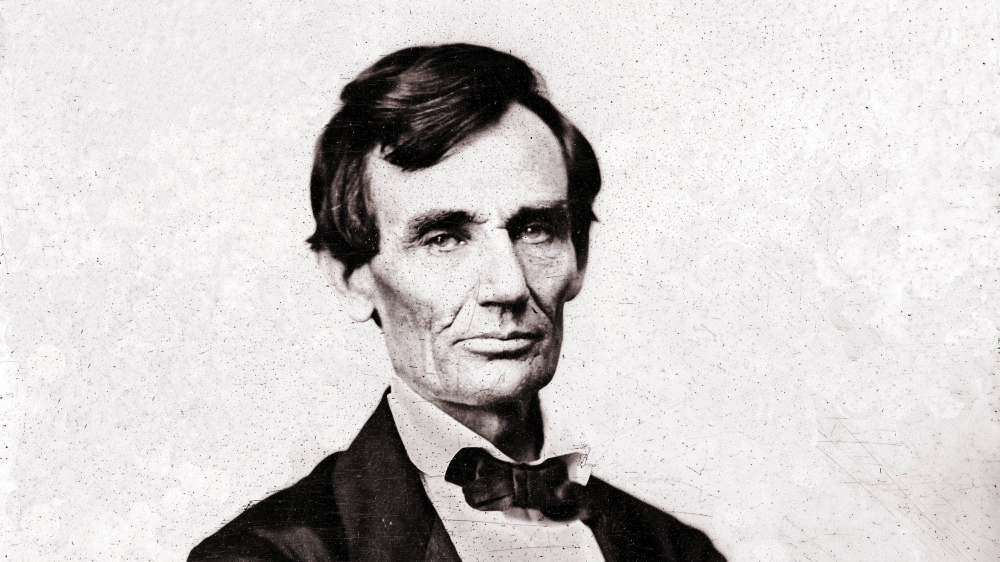

Abraham Lincoln, August 13, 1860, via Library of Congress.

The electoral landscape was further complicated through the emergence of a fourth candidate, Tennessee’s John Bell, heading the Constitutional Union Party. Lincoln carried all free states with the exception of New Jersey (which he split with Douglas). 81.2% of the voting electorate came out to vote—at that point the highest ever for a presidential election. But, Lincoln’s 180 electoral votes came with under 40% of the popular vote. Lincoln was trailed by Breckenridge with his 72 electoral votes, carrying 11 of the 15 slave states, Bell came in third with 39 electoral votes, with Douglas coming in last, only able to garner twelve electoral votes despite carrying almost 30% of the popular vote. All future Confederate states, with the exception of Virginia, excluded Lincoln’s name from their ballots, making the victory even more remarkable.

South Carolina acted almost immediately, calling a convention to declare secession. On December 20, 1860, the South Carolina convention voted unanimously 169-0 to dissolve their Union with the United States. The other states across the Deep South soon followed suit. Mississippi adopted their own resolution on January 9, 1861, Florida followed on January 10, Alabama January 11, Georgia on January 19, Louisiana on January 26, and Texas on February 1. While Texas was the only state to put the issue up for vote amongst the entire voting population, most other states hovered around an 80% vote in favor of secession at their respective conventions.

President James Buchanan would not directly address the issue of secession prior to his term’s end in early March. Any effort to try and solve the issue therefore fell upon Congress, specifically a “Committee of Thirteen” including prominent men such as Stephen Douglas, William Seward, Robert Toombs, and John Crittenden. In what became known as “Crittenden’s Compromise,” Senator Crittenden proposed a series of Constitutional Amendments that guaranteed slavery in southern states states/territories, denied the Federal Government interstate slave trade regulatory power, and offered to compensate slave owners of unrecovered fugitive slaves. The Committee of Thirteen ultimately voted down the measure and it likewise failed in the full Senate vote (25-23). Prospects for reconciliation appeared grim.

The seven seceding states met in Montgomery, Alabama on February 4th to organize a new nation. The delegates selected Jefferson Davis of Mississippi as president and established a capital in Montgomery, Alabama (it would move to Richmond in May). When Davis received the telegram, his wife later wrote, “he looked so grieved that I feared some evil had befallen our family. After a few minutes he told me like a man might speak of a sentence of death.” Out of a sense of duty, Davis accepted. Whether the states of the Upper South would join the Confederacy remained uncertain. By the early spring of 1861, North Carolina and Tennessee had not held secession conventions, while others in Virginia, Missouri, and Arkansas initially voted down secession. Despite this boost to the Union, it became abundantly clear that these acts of loyalty in the Upper South were highly conditional and relied on a clear lack of intervention on the part of the Federal government. This was the situation facing Abraham Lincoln on his inauguration in March 4, 1861.

Candela Citations

- American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html. Project: American Yawp. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike