Learning Outcomes

- Write the definition of the natural logarithm as an integral

- Recognize the derivative of the natural logarithm

- Integrate functions involving the natural logarithmic function

- Define the number 𝑒 through an integral

The Natural Logarithm as an Integral

Recall the power rule for integrals:

Clearly, this does not work when [latex]n=-1,[/latex] as it would force us to divide by zero. So, what do we do with [latex]\displaystyle\int \frac{1}{x}dx?[/latex] Recall from the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus that [latex]{\displaystyle\int }_{1}^{x}\dfrac{1}{t}dt[/latex] is an antiderivative of [latex]\frac{1}{x}.[/latex] Therefore, we can make the following definition.

Definition

For [latex]x>0,[/latex] define the natural logarithm function by

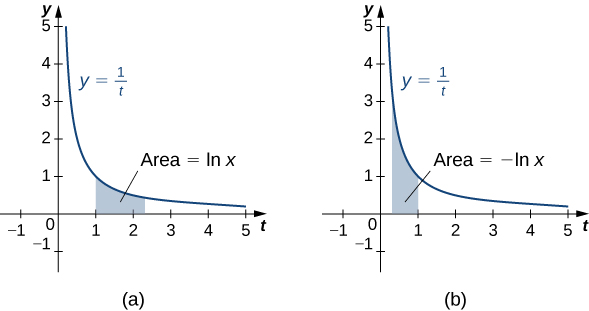

For [latex]x>1,[/latex] this is just the area under the curve [latex]y=1\text{/}t[/latex] from 1 to [latex]x.[/latex] For [latex]x<1,[/latex] we have [latex]{\displaystyle\int }_{1}^{x}\frac{1}{t}dt=\text{−}{\displaystyle\int }_{x}^{1}\frac{1}{t}dt,[/latex] so in this case it is the negative of the area under the curve from [latex]x\text{ to }1[/latex] (see the following figure).

Figure 1. (a) When [latex]x>1,[/latex] the natural logarithm is the area under the curve [latex]y=\frac{1}{t}[/latex] from [latex]1\text{ to }x.[/latex] (b) When [latex]x<1,[/latex] the natural logarithm is the negative of the area under the curve from [latex]x[/latex] to 1.

Notice that [latex]\text{ln}1=0.[/latex] Furthermore, the function [latex]y=\frac{1}{t}>0[/latex] for [latex]x>0.[/latex] Therefore, by the properties of integrals, it is clear that [latex]\text{ln}x[/latex] is increasing for [latex]x>0.[/latex]

Properties of the Natural Logarithm

Because of the way we defined the natural logarithm, the following differentiation formula falls out immediately as a result of to the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus.

Derivative of the Natural Logarithm

For [latex]x>0,[/latex] the derivative of the natural logarithm is given by

Corollary to the Derivative of the Natural Logarithm

The function [latex]\text{ln}x[/latex] is differentiable; therefore, it is continuous.

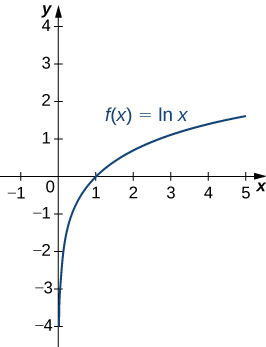

A graph of [latex]\text{ln}x[/latex] is shown in Figure 2. Notice that it is continuous throughout its domain of [latex](0,\infty ).[/latex]

Figure 2. The graph of [latex]f(x)=\text{ln}x[/latex] shows that it is a continuous function.

Example: Calculating Derivatives of Natural Logarithms

Calculate the following derivatives:

- [latex]\frac{d}{dx}\text{ln}(5{x}^{3}-2)[/latex]

- [latex]\frac{d}{dx}{(\text{ln}(3x))}^{2}[/latex]

Try It

Calculate the following derivatives:

- [latex]\frac{d}{dx}\text{ln}(2{x}^{2}+x)[/latex]

- [latex]\frac{d}{dx}{(\text{ln}({x}^{3}))}^{2}[/latex]

Watch the following video to see the worked solution to the above Try It.

Try It

Note that if we use the absolute value function and create a new function [latex]\text{ln}|x|,[/latex] we can extend the domain of the natural logarithm to include [latex]x<0.[/latex] Then [latex](d\text{/}(dx))\text{ln}|x|=1\text{/}x.[/latex] This gives rise to the familiar integration formula.

Integral of (1/[latex]u[/latex]) du

The natural logarithm is the antiderivative of the function [latex]f(u)=1\text{/}u\text{:}[/latex]

Example: Calculating Integrals Involving Natural Logarithms

Calculate the integral [latex]\displaystyle\int \frac{x}{{x}^{2}+4}dx.[/latex]

Try It

Calculate the integral [latex]\displaystyle\int \frac{{x}^{2}}{{x}^{3}+6}dx.[/latex]

Watch the following video to see the worked solution to the above Try It.

Try It

Although we have called our function a “logarithm,” we have not actually proved that any of the properties of logarithms hold for this function. We do so here.

Properties of the Natural Logarithm

If [latex]a,b>0[/latex] and [latex]r[/latex] is a rational number, then

- [latex]\text{ln}1=0[/latex]

- [latex]\text{ln}(ab)=\text{ln}a+\text{ln}b[/latex]

- [latex]\text{ln}(\frac{a}{b})=\text{ln}a-\text{ln}b[/latex]

- [latex]\text{ln}({a}^{r})=r\text{ln}a[/latex]

Proof

- By definition, [latex]\text{ln}1={\displaystyle\int }_{1}^{1}\frac{1}{t}dt=0.[/latex]

- We have

[latex]\text{ln}(ab)={\displaystyle\int }_{1}^{ab}\frac{1}{t}dt={\displaystyle\int }_{1}^{a}\frac{1}{t}dt+{\displaystyle\int }_{a}^{ab}\frac{1}{t}dt.[/latex]

Use [latex]u\text{-substitution}[/latex] on the last integral in this expression. Let [latex]u=t\text{/}a.[/latex] Then [latex]du=(1\text{/}a)dt.[/latex] Furthermore, when [latex]t=a,u=1,[/latex] and when [latex]t=ab,u=b.[/latex] So we get

[latex]\text{ln}(ab)={\displaystyle\int }_{1}^{a}\frac{1}{t}dt+{\displaystyle\int }_{a}^{ab}\frac{1}{t}dt={\displaystyle\int }_{1}^{a}\frac{1}{t}dt+{\displaystyle\int }_{1}^{ab}\frac{a}{t}·\frac{1}{a}dt={\displaystyle\int }_{1}^{a}\frac{1}{t}dt+{\displaystyle\int }_{1}^{b}\frac{1}{u}du=\text{ln}a+\text{ln}b.[/latex] - Note that

[latex]\frac{d}{dx}\text{ln}({x}^{r})=\frac{r{x}^{r-1}}{{x}^{r}}=\frac{r}{x}.[/latex]

Furthermore,

[latex]\frac{d}{dx}(r\text{ln}x)=\frac{r}{x}.[/latex]Since the derivatives of these two functions are the same, by the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, they must differ by a constant. So we have

[latex]\text{ln}({x}^{r})=r\text{ln}x+C[/latex]for some constant [latex]C.[/latex] Taking [latex]x=1,[/latex] we get

[latex]\begin{array}{ccc}\hfill \text{ln}({1}^{r})& =\hfill & r\text{ln}(1)+C\hfill \\ \hfill 0& =\hfill & r(0)+C\hfill \\ \hfill C& =\hfill & 0.\hfill \end{array}[/latex]Thus [latex]\text{ln}({x}^{r})=r\text{ln}x[/latex] and the proof is complete. Note that we can extend this property to irrational values of [latex]r[/latex] later in this section.

Part iii. follows from parts ii. and iv. and the proof is left to you.

[latex]_\blacksquare[/latex]

Example: Using Properties of Logarithms

Use properties of logarithms to simplify the following expression into a single logarithm:

Try It

Use properties of logarithms to simplify the following expression into a single logarithm:

Defining the Number [latex]e[/latex]

Now that we have the natural logarithm defined, we can use that function to define the number [latex]e.[/latex]

Definition

The number [latex]e[/latex] is defined to be the real number such that

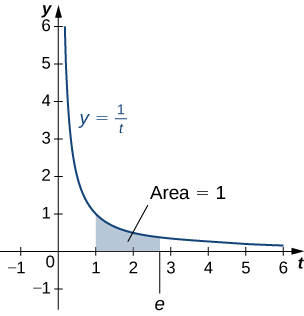

To put it another way, the area under the curve [latex]y=1\text{/}t[/latex] between [latex]t=1[/latex] and [latex]t=e[/latex] is 1 (Figure 3). The proof that such a number exists and is unique is left to you. (Hint: Use the Intermediate Value Theorem to prove existence and the fact that [latex]\text{ln}x[/latex] is increasing to prove uniqueness.)

Figure 3. The area under the curve from 1 to [latex]e[/latex] is equal to one.

The number [latex]e[/latex] can be shown to be irrational, although we won’t do so here (see the activity in Taylor and Maclaurin Series in Calculus 2). Its approximate value is given by

Candela Citations

- 6.7 Try It Problems. Authored by: Ryan Melton. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Calculus Volume 1. Authored by: Gilbert Strang, Edwin (Jed) Herman. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: https://openstax.org/details/books/calculus-volume-1. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/calculus-volume-1/pages/1-introduction