Learning Outcomes

- Calculate the work done by a variable force acting along a line

- Calculate the work done in pumping a liquid from one height to another

- Find the hydrostatic force against a submerged vertical plate

Work Done by a Force

We now consider work. In physics, work is related to force, which is often intuitively defined as a push or pull on an object. When a force moves an object, we say the force does work on the object. In other words, work can be thought of as the amount of energy it takes to move an object. According to physics, when we have a constant force, work can be expressed as the product of force and distance.

In the English system, the unit of force is the pound and the unit of distance is the foot, so work is given in foot-pounds. In the metric system, kilograms and meters are used. One newton is the force needed to accelerate 1 kilogram of mass at the rate of 1 m/sec2. Thus, the most common unit of work is the newton-meter. This same unit is also called the joule. Both are defined as kilograms times meters squared over seconds squared [latex](\text{kg}·{\text{m}}^{2}\text{/}{\text{s}}^{2}).[/latex]

When we have a constant force, things are pretty easy. It is rare, however, for a force to be constant. The work done to compress (or elongate) a spring, for example, varies depending on how far the spring has already been compressed (or stretched). We look at springs in more detail later in this section.

Suppose we have a variable force [latex]F(x)[/latex] that moves an object in a positive direction along the [latex]x[/latex]-axis from point [latex]a[/latex] to point [latex]b.[/latex] To calculate the work done, we partition the interval [latex]\left[a,b\right][/latex] and estimate the work done over each subinterval. So, for [latex]i=0,1,2\text{,…},n,[/latex] let [latex]P=\left\{{x}_{i}\right\}[/latex] be a regular partition of the interval [latex]\left[a,b\right],[/latex] and for [latex]i=1,2\text{,…},n,[/latex] choose an arbitrary point [latex]{x}_{i}^{*}\in \left[{x}_{i-1},{x}_{i}\right].[/latex] To calculate the work done to move an object from point [latex]{x}_{i-1}[/latex] to point [latex]{x}_{i},[/latex] we assume the force is roughly constant over the interval, and use [latex]F({x}_{i}^{*})[/latex] to approximate the force. The work done over the interval [latex]\left[{x}_{i-1},{x}_{i}\right],[/latex] then, is given by

Therefore, the work done over the interval [latex]\left[a,b\right][/latex] is approximately

Taking the limit of this expression as [latex]n\to \infty[/latex] gives us the exact value for work:

Thus, we can define work as follows.

Definition

If a variable force [latex]F(x)[/latex] moves an object in a positive direction along the [latex]x[/latex]-axis from point [latex]a[/latex] to point [latex]b[/latex], then the work done on the object is

Note that if F is constant, the integral evaluates to [latex]F·(b-a)=F·d,[/latex] which is the formula we stated at the beginning of this section.

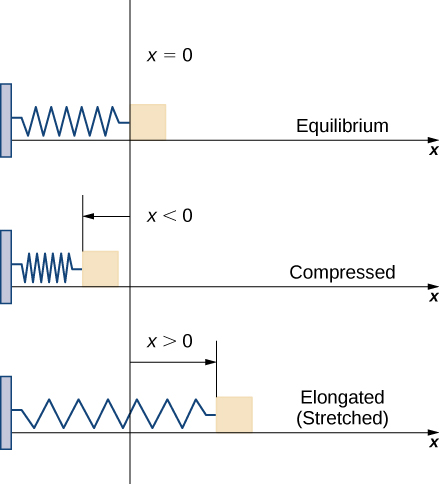

Now let’s look at the specific example of the work done to compress or elongate a spring. Consider a block attached to a horizontal spring. The block moves back and forth as the spring stretches and compresses. Although in the real world we would have to account for the force of friction between the block and the surface on which it is resting, we ignore friction here and assume the block is resting on a frictionless surface. When the spring is at its natural length (at rest), the system is said to be at equilibrium. In this state, the spring is neither elongated nor compressed, and in this equilibrium position the block does not move until some force is introduced. We orient the system such that [latex]x=0[/latex] corresponds to the equilibrium position (see the following figure).

Figure 4. A block attached to a horizontal spring at equilibrium, compressed, and elongated.

According to Hooke’s law, the force required to compress or stretch a spring from an equilibrium position is given by [latex]F(x)=kx,[/latex] for some constant [latex]k.[/latex] The value of [latex]k[/latex] depends on the physical characteristics of the spring. The constant [latex]k[/latex] is called the spring constant and is always positive. We can use this information to calculate the work done to compress or elongate a spring, as shown in the following example.

Example: The Work Required to Stretch or Compress a Spring

Suppose it takes a force of 10 N (in the negative direction) to compress a spring 0.2 m from the equilibrium position. How much work is done to stretch the spring 0.5 m from the equilibrium position?

Try It

Suppose it takes a force of 8 lb to stretch a spring 6 in. from the equilibrium position. How much work is done to stretch the spring 1 ft from the equilibrium position?

Watch the following video to see the worked solution to the above Try It.

Try It

Work Done in Pumping

Consider the work done to pump water (or some other liquid) out of a tank. Pumping problems are a little more complicated than spring problems because many of the calculations depend on the shape and size of the tank. In addition, instead of being concerned about the work done to move a single mass, we are looking at the work done to move a volume of water, and it takes more work to move the water from the bottom of the tank than it does to move the water from the top of the tank.

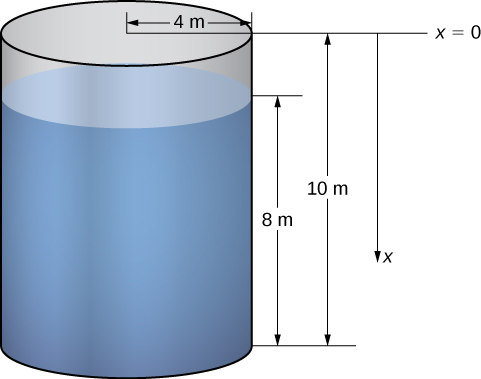

We examine the process in the context of a cylindrical tank, then look at a couple of examples using tanks of different shapes. Assume a cylindrical tank of radius 4 m and height 10 m is filled to a depth of 8 m. How much work does it take to pump all the water over the top edge of the tank?

The first thing we need to do is define a frame of reference. We let [latex]x[/latex] represent the vertical distance below the top of the tank. That is, we orient the [latex]x\text{-axis}[/latex] vertically, with the origin at the top of the tank and the downward direction being positive (see the following figure).

Figure 5. How much work is needed to empty a tank partially filled with water?

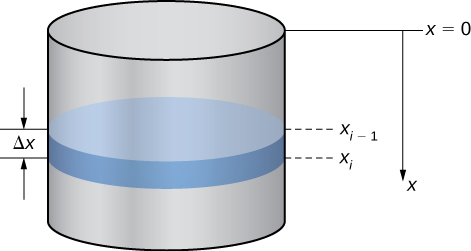

Using this coordinate system, the water extends from [latex]x=2[/latex] to [latex]x=10.[/latex] Therefore, we partition the interval [latex]\left[2,10\right][/latex] and look at the work required to lift each individual “layer” of water. So, for [latex]i=0,1,2\text{,…},n,[/latex] let [latex]P=\left\{{x}_{i}\right\}[/latex] be a regular partition of the interval [latex]\left[2,10\right],[/latex] and for [latex]i=1,2\text{,…},n,[/latex] choose an arbitrary point [latex]{x}_{i}^{*}\in \left[{x}_{i-1},{x}_{i}\right].[/latex] (Figure 6) shows a representative layer.

Figure 6. A representative layer of water.

In pumping problems, the force required to lift the water to the top of the tank is the force required to overcome gravity, so it is equal to the weight of the water. Given that the weight-density of water is 9800 N/m3, or 62.4 lb/ft3, calculating the volume of each layer gives us the weight. In this case, we have

Then, the force needed to lift each layer is

Note that this step becomes a little more difficult if we have a noncylindrical tank. We look at a noncylindrical tank in the next example.

We also need to know the distance the water must be lifted. Based on our choice of coordinate systems, we can use [latex]{x}_{i}^{*}[/latex] as an approximation of the distance the layer must be lifted. Then the work to lift the [latex]i\text{th}[/latex] layer of water [latex]{W}_{i}[/latex] is approximately

Adding the work for each layer, we see the approximate work to empty the tank is given by

This is a Riemann sum, so taking the limit as [latex]n\to \infty ,[/latex] we get

The work required to empty the tank is approximately 23,650,000 J.

For pumping problems, the calculations vary depending on the shape of the tank or container. The following problem-solving strategy lays out a step-by-step process for solving pumping problems.

Problem-Solving Strategy: Solving Pumping Problems

- Sketch a picture of the tank and select an appropriate frame of reference.

- Calculate the volume of a representative layer of water.

- Multiply the volume by the weight-density of water to get the force.

- Calculate the distance the layer of water must be lifted.

- Multiply the force and distance to get an estimate of the work needed to lift the layer of water.

- Sum the work required to lift all the layers. This expression is an estimate of the work required to pump out the desired amount of water, and it is in the form of a Riemann sum.

- Take the limit as [latex]n\to \infty[/latex] and evaluate the resulting integral to get the exact work required to pump out the desired amount of water.

We now apply this problem-solving strategy in an example with a noncylindrical tank.

Example: A Pumping Problem with a Noncylindrical Tank

Assume a tank in the shape of an inverted cone, with height 12 ft and base radius 4 ft. The tank is full to start with, and water is pumped over the upper edge of the tank until the height of the water remaining in the tank is 4 ft. How much work is required to pump out that amount of water?

Watch the following video to see the worked solution to Example: A Pumping Problem with a Noncylindrical Tank.

Try It

A tank is in the shape of an inverted cone, with height 10 ft and base radius 6 ft. The tank is filled to a depth of 8 ft to start with, and water is pumped over the upper edge of the tank until 3 ft of water remain in the tank. How much work is required to pump out that amount of water?

Try It

Hydrostatic Force and Pressure

In this last section, we look at the force and pressure exerted on an object submerged in a liquid. In the English system, force is measured in pounds. In the metric system, it is measured in newtons. Pressure is force per unit area, so in the English system we have pounds per square foot (or, perhaps more commonly, pounds per square inch, denoted psi). In the metric system we have newtons per square meter, also called pascals.

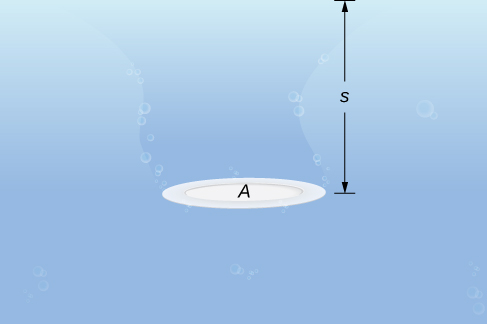

Let’s begin with the simple case of a plate of area [latex]A[/latex] submerged horizontally in water at a depth [latex]s[/latex] (Figure 9). Then, the force exerted on the plate is simply the weight of the water above it, which is given by [latex]F=\rho As,[/latex] where [latex]\rho[/latex] is the weight density of water (weight per unit volume). To find the hydrostatic pressure—that is, the pressure exerted by water on a submerged object—we divide the force by the area. So the pressure is [latex]p=F\text{/}A=\rho s.[/latex]

Figure 9. A plate submerged horizontally in water.

By Pascal’s principle, the pressure at a given depth is the same in all directions, so it does not matter if the plate is submerged horizontally or vertically. So, as long as we know the depth, we know the pressure. We can apply Pascal’s principle to find the force exerted on surfaces, such as dams, that are oriented vertically. We cannot apply the formula [latex]F=\rho As[/latex] directly, because the depth varies from point to point on a vertically oriented surface. So, as we have done many times before, we form a partition, a Riemann sum, and, ultimately, a definite integral to calculate the force.

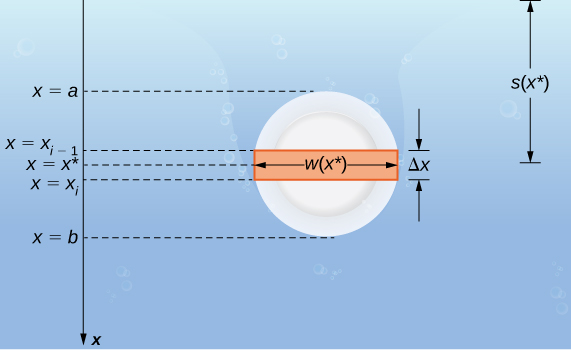

Suppose a thin plate is submerged in water. We choose our frame of reference such that the [latex]x[/latex]-axis is oriented vertically, with the downward direction being positive, and point [latex]x=0[/latex] corresponding to a logical reference point. Let [latex]s(x)[/latex] denote the depth at point [latex]x[/latex]. Note we often let [latex]x=0[/latex] correspond to the surface of the water. In this case, depth at any point is simply given by [latex]s(x)=x.[/latex] However, in some cases we may want to select a different reference point for [latex]x=0,[/latex] so we proceed with the development in the more general case. Last, let [latex]w(x)[/latex] denote the width of the plate at the point [latex]x.[/latex]

Assume the top edge of the plate is at point [latex]x=a[/latex] and the bottom edge of the plate is at point [latex]x=b.[/latex] Then, for [latex]i=0,1,2\text{,…},n,[/latex] let [latex]P=\left\{{x}_{i}\right\}[/latex] be a regular partition of the interval [latex]\left[a,b\right],[/latex] and for [latex]i=1,2\text{,…},n,[/latex] choose an arbitrary point [latex]{x}_{i}^{*}\in \left[{x}_{i-1},{x}_{i}\right].[/latex] The partition divides the plate into several thin, rectangular strips (see the following figure).

Figure 10. A thin plate submerged vertically in water.

Let’s now estimate the force on a representative strip. If the strip is thin enough, we can treat it as if it is at a constant depth, [latex]s({x}_{i}^{*}).[/latex] We then have

Adding the forces, we get an estimate for the force on the plate:

This is a Riemann sum, so taking the limit gives us the exact force. We obtain

Evaluating this integral gives us the force on the plate. We summarize this in the following problem-solving strategy.

Problem-Solving Strategy: Finding Hydrostatic Force

- Sketch a picture and select an appropriate frame of reference. (Note that if we select a frame of reference other than the one used earlier, we may have to adjust the equation above accordingly.)

- Determine the depth and width functions, [latex]s(x)[/latex] and [latex]w(x).[/latex]

- Determine the weight-density of whatever liquid with which you are working. The weight-density of water is 62.4 lb/ft3, or 9800 N/m3.

- Use the equation to calculate the total force.

Example: Finding Hydrostatic Force

A water trough 15 ft long has ends shaped like inverted isosceles triangles, with base 8 ft and height 3 ft. Find the force on one end of the trough if the trough is full of water.

Try It

A water trough 12 m long has ends shaped like inverted isosceles triangles, with base 6 m and height 4 m. Find the force on one end of the trough if the trough is full of water.

Watch the following video to see the worked solution to the above Try It.

Try It

When the reservoir is at its average level, the surface of the water is about 50 ft below where it would be if the reservoir were full. What is the force on the face of the dam under these circumstances?

Try It

Candela Citations

- 2.5 Physical Applications. Authored by: Ryan Melton. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Calculus Volume 1. Authored by: Gilbert Strang, Edwin (Jed) Herman. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: https://openstax.org/details/books/calculus-volume-1. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/calculus-volume-1/pages/1-introduction

Hint

Follow the problem-solving strategy and the process from the previous example.