Conic sections have been studied since the time of the ancient Greeks, and were considered to be an important mathematical concept. As early as 320 BCE, such Greek mathematicians as Menaechmus, Appollonius, and Archimedes were fascinated by these curves. Appollonius wrote an entire eight-volume treatise on conic sections in which he was, for example, able to derive a specific method for identifying a conic section through the use of geometry. Since then, important applications of conic sections have arisen (for example, in astronomy), and the properties of conic sections are used in radio telescopes, satellite dish receivers, and even architecture. In this section we discuss the three basic conic sections, some of their properties, and their equations.

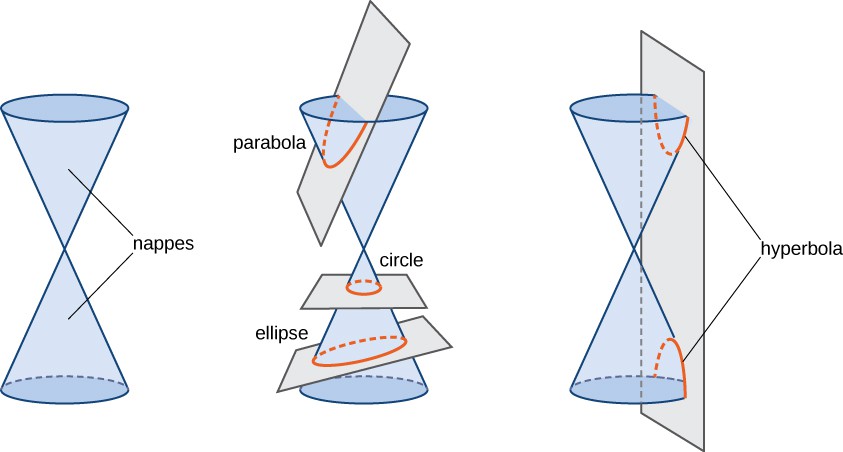

Conic sections get their name because they can be generated by intersecting a plane with a cone. A cone has two identically shaped parts called nappes. One nappe is what most people mean by “cone,” having the shape of a party hat. A right circular cone can be generated by revolving a line passing through the origin around the y-axis as shown.

![The line y = 3x is drawn and then rotated around the [latex]y[/latex]-axis to create two nappes, that is, a cone that is both above and below the x axis.](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/courses-images/wp-content/uploads/sites/4175/2019/04/09225325/CNX_Calc_Figure_11_05_001.jpg)

Figure 1. A cone generated by revolving the line [latex]y=3x[/latex] around the [latex]y[/latex] -axis.

Conic sections are generated by the intersection of a plane with a cone (Figure 2). If the plane is parallel to the axis of revolution (the y-axis), then the conic section is a hyperbola. If the plane is parallel to the generating line, the conic section is a parabola. If the plane is perpendicular to the axis of revolution, the conic section is a circle. If the plane intersects one nappe at an angle to the axis (other than [latex]90^{\circ}[/latex]), then the conic section is an ellipse.

Figure 2. The four conic sections. Each conic is determined by the angle the plane makes with the axis of the cone.

Candela Citations

- Calculus Volume 3. Authored by: Gilbert Strang, Edwin (Jed) Herman. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/calculus-volume-3/pages/1-introduction. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/calculus-volume-3/pages/1-introduction