Self-Awareness

During the second year of life, children begin to recognize themselves as they gain a sense of the self as an object. The realization that one’s body, mind, and activities are distinct from those of other people is known as self-awareness (Kopp, 2011). The most common technique used in research for testing self-awareness in infants is a mirror test known as the “Rouge Test.” The rouge test works by applying a dot of rouge (colored makeup) on an infant’s face and then placing them in front of the mirror. If the infant investigates the dot on their nose by touching it, they are thought to realize their own existence and have achieved self-awareness. A number of research studies have used this technique and shown self-awareness to develop between 15 and 24 months of age. Some researchers also take language such as “I, me, my, etc.” as an indicator of self-awareness.

Cognitive psychologist Philippe Rochat (2003) described a more in-depth developmental path in acquiring self-awareness through various stages. He described self-awareness as occurring in five stages beginning from birth.

| Table 1. Stages of acquiring self-awareness | |

|---|---|

| Stage | Description |

| Stage 1 – Differentiation (from birth) | Right from birth infants are able to differentiate the self from the non-self. A study using the infant rooting reflex found that infants rooted significantly less from self-stimulation, contrary to when the stimulation came from the experimenter. |

| Stage 2 – Situation (by 2 months) | In addition to differentiation, infants at this stage can also situate themselves in relation to a model. In one experiment infants were able to imitate tongue orientation from an adult model. Additionally, another sign of differentiation is when infants bring themselves into contact with objects by reaching for them. |

| Stage 3 – Identification (by 2 years) | At this stage, the more common definition of “self-awareness” comes into play, where infants can identify themselves in a mirror through the “rouge test” as well as begin to use language to refer to themselves. |

| Stage 4 – Permanence | This stage occurs after infancy when children are aware that their sense of self continues to exist across both time and space. |

| Stage 5 – Self-consciousness or meta-self-awareness | This also occurs after infancy. This is the final stage when children can see themselves in 3rd person, or how they are perceived by others. |

Once a child has achieved self-awareness, the child is moving toward understanding social emotions such as guilt, shame or embarrassment, and pride, as well as sympathy and empathy. These will require an understanding of the mental state of others which is acquired around age 3 to 5 and will be explored in the next module (Berk, 2007).

Watch It

Video 1. This video shows one study that demonstrates how toddlers become self-aware around 18 months.

Developing a Concept of Self

Early childhood is a time of forming an initial sense of self. A self-concept or idea of who we are, what we are capable of doing, and how we think and feel is a social process that involves taking into consideration how others view us. It might be said, then, that in order to develop a sense of self, you must have interaction with others. Interactionist theorists, Cooley and Mead offer two interesting explanations of how a sense of self develops.

Video 2. Self-Concept, Self-Identity, and Social Identity explains the various types of self and the formation of identity.

Cooley’s Looking-Glass Self

Charles Horton Cooley (1964) suggested that our self-concept comes from looking at how others respond to us. This process, known as the looking-glass self involves looking at how others seem to view us and interpreting this as we make judgments about whether we are good or bad, strong or weak, beautiful or ugly, and so on. Of course, we do not always interpret their responses accurately so our self-concept is not simply a mirror reflection of the views of others. After forming an initial self-concept, we may use our existing self-concept as a mental filter screening out those responses that do not seem to fit our ideas of who we are. So compliments may be negated, for example.

Think of times in your life when you felt more self-conscious. The process of the looking-glass self is pronounced when we are preschoolers. Later in life, we also experience this process when we are in a new school, new job, or are taking on a new role in our personal lives and are trying to gauge our own performance. When we feel more sure of who we are we focus less on how we appear to others.

Video 3. Charles Cooley–Looking Glass Self explains more about this theory.

Mead’s I and Me

George Herbert Mead (1967) offered an explanation of how we develop a social sense of self by being able to see ourselves through the eyes of others. There are two parts of the self: the “I” which is the part of the self that is spontaneous, creative, innate, and is not concerned with how others view us and the “me” or the social definition of who we are.

When we are born, we are all “I” and act without concern about how others view us. But the socialized self begins when we are able to consider how one important person views us. This initial stage is called “taking the role of the significant other.” For example, a child may pull a cat’s tail and be told by his mother, “No! Don’t do that, that’s bad” while receiving a slight slap on the hand. Later, the child may mimic the same behavior toward the self and say aloud, “No, that’s bad” while patting his own hand. What has happened? The child is able to see himself through the eyes of the mother. As the child grows and is exposed to many situations and rules of culture, he begins to view the self in the eyes of many others through these cultural norms or rules. This is referred to as “taking the role of the generalized other” and results in a sense of self with many dimensions. The child comes to have a sense of self as a student, as a friend, as a son, and so on.

Video 4. George Herbert Mead–The I and the Me explains more about this theory.

Exaggerated Sense of Self

One of the ways to gain a clearer sense of self is to exaggerate those qualities that are to be incorporated into the self. Preschoolers often like to exaggerate their own qualities or to seek validation as the biggest or smartest or child who can jump the highest. Much of this may be due to the simple fact that the child does not understand their own limits. Young children may really believe that they can beat their parent to the mailbox, or pick up the refrigerator.

This exaggeration tends to be replaced by a more realistic sense of self in middle childhood as children realize that they do have limitations. Part of this process includes having parents who allow children to explore their capabilities and give the child authentic feedback. Another important part of this process involves the child learning that other people have capabilities, too and that the child’s capabilities may differ from those of other people. Children learn to compare themselves to others to understand what they are “good at” and what they are not as good at.

Children in middle childhood have a more realistic sense of self than do those in early childhood. That exaggerated sense of self as “biggest” or “smartest” or “tallest” gives way to an understanding of one’s strengths and weaknesses. This can be attributed to greater experience in comparing one’s own performance with that of others and to greater cognitive flexibility. A child’s self-concept can be influenced by peers, family, teachers, and the messages they send about a child’s worth. Contemporary children also receive messages from the media about how they should look and act. Movies, music videos, the internet, and advertisers can all create cultural images of what is desirable or undesirable and this too can influence a child’s self-concept.

Self-Efficacy

Imagine two students, Sally and Lucy, who are about to take the same math test. Sally and Lucy have the same exact ability to do well in math, the same level of intelligence, and the same motivation to do well on the test. They also studied together. They even have the same brand of shoes on. The only difference between the two is that Sally is very confident in her mathematical and her test-taking abilities, while Lucy is not. So, who is likely to do better on the test? Sally, of course, because she has the confidence to use her mathematical and test-taking abilities to deal with challenging math problems and to accomplish goals that are important to her—in this case, doing well on the test. This difference between Sally and Lucy—the student who got the A and the student who got the B-, respectively—is self-efficacy. Self-efficacy influences behavior and emotions in particular ways that help people better manage challenges and achieve valued goals.

A concept that was first introduced by Albert Bandura in 1977, self-efficacy refers to a person’s belief that he or she is able to effectively perform the tasks needed to attain a valued goal (Bandura, 1977). Since then, self-efficacy has become one of the most thoroughly researched concepts in psychology. Just about every important domain of human behavior has been investigated using self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1997; Maddux, 1995; Maddux & Gosselin, 2011, 2012). Self-efficacy does not refer to your abilities but rather to your beliefs about what you can do with your abilities. Also, self-efficacy is not a trait—there are not certain types of people with high self-efficacies and others with low self-efficacies (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). Rather, people have self-efficacy beliefs about specific goals and life domains. For example, if you believe that you have the skills necessary to do well in school and believe you can use those skills to excel, then you have high academic self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy may sound similar to a concept you may be familiar with already—self-esteem—but these are very different notions. Self-esteem refers to how much you like or “esteem” yourself—to what extent you believe you are a good and worthwhile person. Self-efficacy, however, refers to your self-confidence to perform well and to achieve in specific areas of life such as school, work, and relationships. Self-efficacy does influence self-esteem because how you feel about yourself overall is greatly influenced by your confidence in your ability to perform well in areas that are important to you and to achieve valued goals. For example, if performing well in athletics is very important to you, then your self-efficacy for athletics will greatly influence your self-esteem; however, if performing well in athletics is not at all important to you, then your self-efficacy for athletics will probably have little impact on your self-esteem.

Self-efficacy begins to develop in very young children. Once self-efficacy is developed, it does not remain constant—it can change and grow as an individual has different experiences throughout his or her lifetime. When children are very young, their parents’ self-efficacies are important (Jones & Prinz, 2005). Children of parents who have high parental self-efficacies perceive their parents as more responsive to their needs (Gondoli & Silverberg, 1997). Around the ages of 12 through 16, adolescents’ friends also become an important source of self-efficacy beliefs. Adolescents who associate with peer groups that are not academically motivated tend to experience a decline in academic self-efficacy (Wentzel, Barry, & Caldwell, 2004). Adolescents who watch their peers succeed, however, experience a rise in academic self-efficacy (Schunk & Miller, 2002). This is an example of gaining self-efficacy through vicarious performances, as discussed above. The effects of self-efficacy that develop in adolescence are long-lasting. One study found that greater social and academic self-efficacy measured in people ages 14 to 18 predicted greater life satisfaction five years later (Vecchio, Gerbino, Pastorelli, Del Bove, & Caprara, 2007).

Video 5. Self-Esteem, Self-Efficacy, and Locus of Control.

Major Influences on Self-Efficacy

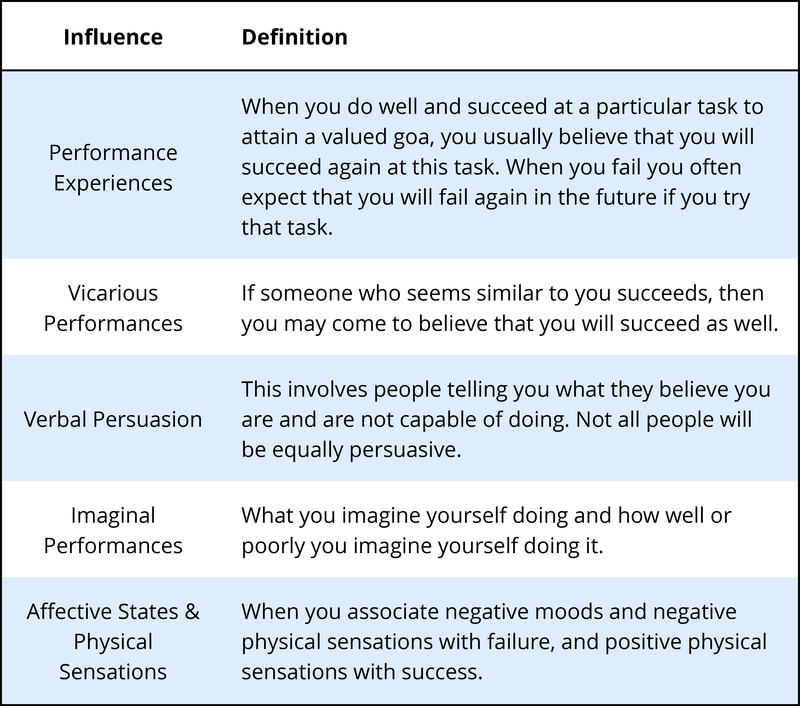

Self-efficacy beliefs are influenced in five different ways (Bandura, 1997), which are summarized in the table below.

These five types of self-efficacy influence can take many real-world forms that almost everyone has experienced. You may have had previous performance experiences affect your academic self-efficacy when you did well on a test and believed that you would do well on the next test. A vicarious performance may have affected your athletic self-efficacy when you saw your best friend skateboard for the first time and thought that you could skateboard well, too. Verbal persuasion could have affected your academic self-efficacy when a teacher that you respect told you that you could get into the college of your choice if you studied hard for the SATs. It’s important to know that not all people are equally likely to influence your self-efficacy through verbal persuasion. People who appear trustworthy or attractive, or who seem to be experts, are more likely to influence your self-efficacy than are people who do not possess these qualities (Petty & Brinol, 2010). That’s why a teacher you respect is more likely to influence your self-efficacy than a teacher you do not respect. Imaginal performances are an effective way to increase your self-efficacy. For example, imagining yourself doing well on a job interview actually leads to more effective interviewing (Knudstrup, Segrest, & Hurley, 2003). Affective states and physical sensations abound when you think about the times you have given presentations in class. For example, you may have felt your heart racing while giving a presentation. If you believe your heart was racing because you had just had a lot of caffeine, it likely would not affect your performance. If you believe your heart was racing because you were doing a poor job, you might believe that you cannot give the presentation well. This is because you associate the feeling of anxiety with failure and expect to fail when you are feeling anxious.

Benefits of High Self-Efficacy

Academic Performance

Consider academic self-efficacy in your own life and recall the earlier example of Sally and Lucy. Are you more like Sally, who has high academic self-efficacy and believes that she can use her abilities to do well in school, or are you more like Lucy, who does not believe that she can effectively use her academic abilities to excel in school? Do you think your own self-efficacy has ever affected your academic ability? Do you think you have ever studied more or less intensely because you did or did not believe in your abilities to do well? Many researchers have considered how self-efficacy works in academic settings, and the short answer is that academic self-efficacy affects every possible area of academic achievement (Pajares, 1996).

Students who believe in their ability to do well academically tend to be more motivated in school (Schunk, 1991). When self-efficacious students attain their goals, they continue to set even more challenging goals (Schunk, 1990). This can all lead to better performance in school in terms of higher grades and taking more challenging classes (Multon, Brown, & Lent, 1991). For example, students with high academic self-efficacies might study harder because they believe that they are able to use their abilities to study effectively. Because they studied hard, they receive an A on their next test. Teachers’ self-efficacies also can affect how well a student performs in school. Self-efficacious teachers encourage parents to take a more active role in their children’s learning, leading to better academic performance (Hoover-Dempsey, Bassler, & Brissie, 1987).

Although there is a lot of research about how self-efficacy is beneficial to school-aged children, college students can also benefit from self-efficacy. Freshmen with higher self-efficacies about their ability to do well in college tend to adapt to their first year in college better than those with lower self-efficacies (Chemers, Hu, & Garcia, 2001). The benefits of self-efficacy continue beyond the school years: people with strong self-efficacy beliefs toward performing well in school tend to perceive a wider range of career options (Lent, Brown, & Larkin, 1986). In addition, people who have stronger beliefs of self-efficacy toward their professional work tend to have more successful careers (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998).

One question you might have about self-efficacy and academic performance is how a student’s actual academic ability interacts with self-efficacy to influence academic performance. The answer is that a student’s actual ability does play a role, but it is also influenced by self-efficacy. Students with greater ability perform better than those with lesser ability. But, among a group of students with the same exact level of academic ability, those with stronger academic self-efficacies outperform those with weaker self-efficacies. One study (Collins, 1984) compared performance on difficult math problems among groups of students with different levels of math ability and different levels of math self-efficacy. Among a group of students with average levels of math ability, the students with weak math self-efficacies got about 25% of the math problems correct. The students with average levels of math ability and strong math self-efficacies got about 45% of the questions correct. This means that by just having stronger math self-efficacy, a student of average math ability will perform 20% better than a student with similar math ability but weaker math self-efficacy. You might also wonder if self-efficacy makes a difference only for people with average or below-average abilities. Self-efficacy is important even for above-average students. In this study, those with above-average math abilities and low math self-efficacies answered only about 65% of the questions correctly; those with above-average math abilities and high math self-efficacies answered about 75% of the questions correctly.

Healthy Behaviors

Think about a time when you tried to improve your health, whether through dieting, exercising, sleeping more, or any other way. Would you be more likely to follow through on these plans if you believed that you could effectively use your skills to accomplish your health goals? Many researchers agree that people with stronger self-efficacies for doing healthy things (e.g., exercise self-efficacy, dieting self-efficacy) engage in more behaviors that prevent health problems and improve overall health (Strecher, DeVellis, Becker, & Rosenstock, 1986). People who have strong self-efficacy beliefs about quitting smoking are able to quit smoking more easily (DiClemente, Prochaska, & Gibertini, 1985). People who have strong self-efficacy beliefs about being able to reduce their alcohol consumption are more successful when treated for drinking problems (Maisto, Connors, & Zywiak, 2000). People who have stronger self-efficacy beliefs about their ability to recover from heart attacks do so more quickly than those who do not have such beliefs (Ewart, Taylor, Reese, & DeBusk, 1983).

One group of researchers (Roach Yadrick, Johnson, Boudreaux, Forsythe, & Billon, 2003) conducted an experiment with people trying to lose weight. All people in the study participated in a weight loss program that was designed for the U.S. Air Force. This program had already been found to be very effective, but the researchers wanted to know if increasing people’s self-efficacies could make the program even more effective. So, they divided the participants into two groups: one group received an intervention that was designed to increase weight loss self-efficacy along with the diet program, and the other group received only the diet program. The researchers tried several different ways to increase self-efficacy, such as having participants read a copy of Oh, The Places You’ll Go! by Dr. Seuss (1990), and having them talk to someone who had successfully lost weight. The people who received the diet program and an intervention to increase self-efficacy lost an average of 8.2 pounds over the 12 weeks of the study; those participants who had only the diet program lost only 5.8 pounds. Thus, just by increasing weight loss self-efficacy, participants were able to lose over 50% more weight.

Studies have found that increasing a person’s nutritional self-efficacy can lead them to eat more fruits and vegetables (Luszczynska, Tryburcy, & Schwarzer, 2006). Self-efficacy plays a large role in successful physical exercise (Maddux & Dawson, 2014). People with stronger self-efficacies for exercising are more likely to plan on beginning an exercise program, actually beginning that program (DuCharme & Brawley, 1995), and continuing it (Marcus, Selby, Niaura, & Rossi, 1992). Self-efficacy is especially important when it comes to safe sex. People with greater self-efficacies about condom usage are more likely to engage in safe sex (Kaneko, 2007), making them more likely to avoid sexually transmitted diseases, such as HIV (Forsyth & Carey, 1998).

Athletic Performance

If you are an athlete, self-efficacy is especially important in your life. Professional and amateur athletes with stronger self-efficacy beliefs about their athletic abilities perform better than athletes with weaker levels of self-efficacy (Wurtele, 1986). This holds true for athletes in all types of sports, including track and field (Gernigon & Delloye, 2003), tennis (Sheldon & Eccles, 2005), and golf (Bruton, Mellalieu, Shearer, Roderique-Davies, & Hall, 2013). One group of researchers found that basketball players with strong athletic self-efficacy beliefs hit more foul shots than did basketball players with weak self-efficacy beliefs (Haney & Long, 1995). These researchers also found that the players who hit more foul shots had greater increases in self-efficacy after they hit the foul shots compared to those who hit fewer foul shots and did not experience increases in self-efficacy. This is an example of how we gain self-efficacy through performance experiences.

Self-Regulation

One of the major reasons that higher self-efficacy usually leads to better performance and greater success is that self-efficacy is an important component of self-regulation. Self-regulation is the complex process through which you control your thoughts, emotions, and actions (Gross, 1998). It is crucial to success and well-being in almost every area of your life. Every day, you are exposed to situations where you might want to act or feel a certain way that would be socially inappropriate or that might be unhealthy for you in the long run. For example, when sitting in a boring class, you might want to take out your phone and text your friends, take off your shoes and take a nap, or perhaps scream because you are so bored. Self-regulation is the process that you use to avoid such behaviors and instead sit quietly through class. Self-regulation takes a lot of effort, and it is often compared to a muscle that can be exhausted (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven, & Tice, 1998). For example, a child might be able to resist eating a pile of delicious cookies if he or she is in the room with the cookies for only a few minutes, but if that child were forced to spend hours with the cookies, his or her ability to regulate the desire to eat the cookies would wear down. Eventually, his or her self-regulatory abilities would be exhausted, and the child would eat the cookies. A person with strong self-efficacy beliefs might become less distressed in the face of failure than might someone with weak self-efficacy. Because self-efficacious people are less likely to become distressed, they draw less on their self-regulation reserves; thus, self-efficacious people persist longer in the face of a challenge.

Self-efficacy influences self-regulation in many ways to produce better performance and greater success (Maddux & Volkmann, 2010). First, people with stronger self-efficacies have greater motivation to perform in the area for which they have stronger self-efficacies (Bandura & Locke, 2003). This means that people are motivated to work harder in those areas where they believe they can effectively perform. Second, people with stronger self-efficacies are more likely to persevere through challenges in attaining goals (Vancouver, More, & Yoder, 2008). For example, people with high academic self-efficacies are better able to motivate themselves to persevere through such challenges as taking a difficult class and completing their degrees because they believe that their efforts will pay off. Third, self-efficacious people believe that they have more control over a situation. Having more control over a situation means that self-efficacious people might be more likely to engage in the behaviors that will allow them to achieve their desired goal. Finally, self-efficacious people have more confidence in their problem-solving abilities and, thus, are able to better use their cognitive resources and make better decisions, especially in the face of challenges and setbacks (Cervone, Jiwani, & Wood, 1991).

Self-regulation is the capacity to alter one’s responses. It is broadly related to the term “self-control”. The term “regulate” means to change something—but not just any change, rather change to bring it into agreement with some idea, such as a rule, a goal, a plan, or a moral principle. To illustrate, when the government regulates how houses are built, that means the government inspects the buildings to check that everything is done “up to code” or according to the rules about good building. In a similar fashion, when you regulate yourself, you watch and change yourself to bring your responses into line with some ideas about how they should be.

People regulate four broad categories of responses. They control their thinking, such as in trying to concentrate or to shut some annoying earworm tune out of their mind. They control their emotions, as in trying to cheer themselves up or to calm down when angry (or to stay angry, if that’s helpful). They control their impulses, as in trying not to eat fattening food, trying to hold one’s tongue, or trying to quit smoking. Last, they try to control their task performances, such as in pushing themselves to keep working when tired and discouraged, or deciding whether to speed up (to get more done) or slow down (to make sure to get it right).

Early Work on Delay of Gratification

Research on self-regulation was greatly stimulated by early experiments conducted by Walter Mischel and his colleagues (e.g., Mischel, 1974) on the capacity to delay gratification, which means being able to refuse current temptations and pleasures to work toward future benefits. In a typical study with what later came to be called the “marshmallow test,” a 4-year-old child would be seated in a room, and a favorite treat such as a cookie or marshmallow was placed on the table. The experimenter would tell the child, “I have to leave for a few minutes and then I’ll be back. You can have this treat any time, but if you can wait until I come back, you can have two of them.” Two treats are better than one, but to get the double treat, the child had to wait. Self-regulation was required to resist that urge to gobble down the marshmallow on the table so as to reap the larger reward.

Many situations in life demand similar delays for the best results. Going to college to get an education often means living in poverty and debt rather than getting a job to earn money right away. But in the long run, the college degree increases your lifetime income by hundreds of thousands of dollars. Very few nonhuman animals can bring themselves to resist immediate temptations so as to pursue future rewards, but this trait is an important key to success in human life.

watch it

Video 6. Watch as a teacher uses the Marshmallow Test, originally conducted by Walter Mischel, to teach her students about self-control. The Marshmallow Test has demonstrated correlations between self-control in preschool and successful outcomes in later life. According to Mischel, young children can learn strategies to delay gratification and resist engaging in impulsive behaviors. A retest of the study completed in 2018 by Watts, Duncan, and Quan found the effects of self-control in young children and the later life outcomes to be minimal and more closely tied to the education level of the mother, rather than self-control.

Benefits of Self-Control

People who are good at self-regulation do better than others in life. Follow-up studies with Mischel’s samples found that the children who resisted temptation and delayed gratification effectively grew into adults who were better than others in school and work, more popular with other people, and who were rated as nicer, better people by teachers and others (Mischel, Shoda, & Peake, 1988; Shoda, Mischel, & Peake, 1990). College students with high self-control get better grades, have better close relationships, manage their emotions better, have fewer problems with drugs and alcohol, are less prone to eating disorders, are better adjusted, have higher self-esteem, and get along better with other people, as compared to people with low self-control (Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, 2004). They are happier and have less stress and conflict (Hofmann, Vohs, Fisher, Luhmann, & Baumeister, 2013). Longitudinal studies have found that children with good self-control go through life with fewer problems, are more successful, are less likely to be arrested or have a child out of wedlock, and enjoy other benefits (Moffitt et al., 2011). Criminologists have concluded that low self-control is a—if not the—key trait for understanding the criminal personality (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990; Pratt & Cullen, 2000).

Some researchers have searched for evidence that too much self-control can be bad (Tangney et al., 2004)—but without success. There is such a thing as being highly inhibited or clinically “over-controlled,” which can impair initiative and reduce happiness, but that does not appear to be an excess of self-regulation. Rather, it may stem from having been punished excessively as a child and, therefore, adopting a fearful, inhibited approach to life. In general, self-control resembles intelligence in that the more one has, the better off one is, and the benefits are found through a broad range of life activities.

Three Ingredients of Effective Self-Regulation

For self-regulation to be effective, three parts or ingredients are involved. The first is standards, which are ideas about how things should (or should not) be. The second is monitoring, which means keeping track of the target behavior that is to be regulated. The third is the capacity to change.

Standards are an indispensable foundation for self-regulation. We already saw that self-regulation means a change in relation to some idea; without such guiding ideas, the change would largely be random and lacking direction. Standards include goals, laws, moral principles, personal rules, other people’s expectations, and social norms. Dieters, for example, typically have a goal in terms of how much weight they wish to lose. They help their self-regulation further by developing standards for how much or how little to eat and what kinds of foods they will eat.

The second ingredient is monitoring. It is hard to regulate something without being aware of it. For example, dieters count their calories. That is, they keep track of how much they eat and how fattening it is. In fact, some evidence suggests that dieters stop keeping track of how much they eat when they break their diet or go on an eating binge, and the failure of monitoring contributes to eating more (Polivy, 1976). Alcohol has been found to impair all sorts of self-regulation, partly because intoxicated persons fail to keep track of their behavior and compare it to their standards.

The combination of standards and monitoring was featured in an influential theory about self-regulation by Carver and Scheier (1981, 1982, 1998). Those researchers started their careers studying self-awareness, which is a key human trait. The study of self-awareness recognized early on that people do not simply notice themselves the way they might notice a tree or car. Rather, self-awareness always seemed to involve comparing oneself to a standard. For example, when a man looks in a mirror, he does not just think, “Oh, there I am,” but more likely thinks, “Is my hair a mess? Do my clothes look good?” Carver and Scheier proposed that the reason for this comparison to standards is that it enables people to regulate themselves, such as by changing things that do not measure up to their standards. In the mirror example, the man might comb his hair to bring it into line with his standards for personal appearance. Good students keep track of their grades, credits, and progress toward their degree and other goals. Athletes keep track of their times, scores, and achievements, as a way to monitor improvement.

The process of monitoring oneself can be compared to how a thermostat operates. The thermostat checks the temperature in the room compares it to a standard (the setting for the desired temperature), and if those do not match, it turns on the heat or air conditioner to change the temperature. It checks again and again, and when the room temperature matches the desired setting, the thermostat turns off the climate control. In the same way, people compare themselves to their personal standards, make changes as needed, and stop working on change once they have met their goals. People feel good not just when they reach their goals but even when they deem they are making good progress (Carver & Scheier, 1990). They feel bad when they are not making sufficient progress.

That brings up the third ingredient, which is the capacity to change oneself. In effective self-regulation, people operate on themselves to bring about these changes. The popular term for this is “willpower,” which suggests some kind of energy is expended in the process. Psychologists hesitate to adopt terms associated with folk wisdom because there are many potential implications. Here, the term is used to refer specifically to some energy that is involved in the capacity to change oneself.

Consistent with the popular notion of willpower, people do seem to expend some energy during self-regulation. Many studies have found that after people exert self-regulation to change some response, they perform worse on the next unrelated task if it too requires self-regulation (Hagger, Wood, Stiff, & Chatzisarantis, 2010). That pattern suggests that some energy such as willpower was used up during the first task, leaving less available for the second task. The term for this state of reduced energy available for self-regulation is ego depletion (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven, & Tice, 1998). Current research provides mixed results on ego depletion, and we need further study to better understand when and how it occurs. It may be that as people go about their daily lives, they gradually become ego-depleted because they are exerting self-control and resisting temptations. Some research suggests that during the state of ego depletion people become less helpful and more aggressive, prone to overeat, misbehave sexually, and express more prejudice (Hofmann, Vohs, & Baumeister, 2012).

Thus, a person’s capacity for self-regulation is not constant, but rather it fluctuates. To be sure, some people are generally better than others at controlling themselves (Tangney et al., 2004). But even someone with excellent self-control may occasionally find that control breaks down under ego depletion. In general, self-regulation can be improved by getting enough sleep and healthy food, and by minimizing other demands on one’s willpower.

There is some evidence that regular exercise of self-control can build up one’s willpower, like strengthening a muscle (Baumeister & Tierney, 2011; Oaten & Cheng, 2006). Even in early adulthood, one’s self-control can be strengthened. Furthermore, research has shown that disadvantaged, minority children who take part in preschool programs such as Head Start (often based on the Perry program) end up doing better in life even as adults. This was thought for a while to be due to increases in intelligence quotient (IQ), but changes in IQ from such programs are at best temporary. Instead, recent work indicates that improvement in self-control and related traits may be what produce the benefits (Heckman, Pinto, & Savelyev, in press). It’s not doing math problems or learning to spell at age 3 that increases subsequent adult success—but rather the benefit comes from having some early practice at planning, getting organized, and following rules.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is defined as one’s thoughts and feelings about one’s self-concept and identity–it is an evaluative judgment about who we are. Most theories on self-esteem state that there is a grand desire, across all genders and ages, to maintain, protect, and enhance their self-esteem.

The emergence of cognitive skills in early childhood results in improved perceptions of the self, but they tend to focus on external qualities, which are referred to as the categorical self. When researchers ask young children to describe themselves, their descriptions tend to include physical descriptors, preferred activities,

and favorite possessions. Thus, the self-description of a 3-year-old might be a 3-year-old girl with red hair, who likes to play with blocks. However, even children as young as three know there is more to themselves than these external characteristics.

Harter and Pike (1984) challenged the method of measuring personality with an open-ended question as they felt that language limitations were hindering the ability of young children to express their self-knowledge. They suggested a change to the method of measuring self-concept in young children, whereby researchers provide statements that ask whether something is true of the child (e.g., “I like to boss people around”, “I am grumpy most of the time”). They discovered that in early childhood, children answer these statements in an internally consistent manner, especially after the age of four (Goodvin, Meyer, Thompson & Hayes, 2008), and often give similar responses to what others (parents and teachers) say about the child (Brown, Mangelsdorf, Agathen, & Ho, 2008; Colwell & Lindsey, 2003).

Young children tend to have a generally positive self-image. This optimism is often the result of a lack of social comparison when making self-evaluations (Ruble, Boggiano, Feldman, & Loeble, 1980), and with comparison between what the child once could do to what they can do now (Kemple, 1995). However, this does not mean that preschool children are exempt from negative self-evaluations. Preschool children with insecure attachments to their caregivers tend to have lower self-esteem at age four (Goodvin et al., 2008). Maternal negative affect (emotional state) was also found by Goodwin and her colleagues to produce more negative

self-evaluations in preschool children.

Remarkably, children begin developing social understanding very early in life and are also able to include other peoples’ appraisals of them into their self-concept, including parents, teachers, peers, culture, and media. Internalizing others’ appraisals and creating social comparison affect children’s self-esteem, which is defined as an evaluation of one’s identity. Children can have individual assessments of how well they perform a variety of activities and also develop an overall, global self-assessment. If there is a discrepancy between how children view themselves and what they consider to be their ideal selves, their self-esteem can be

negatively affected.

In middle childhood, friendships take on new importance as judges of one’s worth, competence, and attractiveness. Friendships provide the opportunity for learning social skills such as how to communicate with others and how to negotiate differences. Children get ideas from one another about how to perform certain tasks, how to gain popularity, what to wear, say, and listen to, and how to act. This society of children marks a transition from a life focused on the family to a life concerned with peers. Peers play a key role in a child’s self-esteem at this age as any parent who has tried to console a rejected child will tell you. No matter how complimentary and encouraging the parent may be, being rejected by friends can only be remedied by renewed acceptance.

In adolescence, teens continue to develop their self-concept. Their ability to think of the possibilities and to reason more abstractly may explain the further differentiation of the self during adolescence. However, the teen’s understanding of self is often full of contradictions. Young teens may see themselves as outgoing but also withdrawn, happy yet often moody, and both smart and completely clueless (Harter, 2012). These contradictions, along with the teen’s growing recognition that their personality and behavior seem to change depending on who they are with or where they are, can lead the young teen to feel like a fraud. With their parents, they may seem angrier and sullen, with their friends they are more outgoing and goofy, and at work, they are quiet and cautious. “Which one is really me?” may be the refrain of the young teenager.

Harter (2012) found that adolescents emphasize traits such as being friendly and considerate more than do children, highlighting their increasing concern about how others may see them. Harter also found that older teens add values and moral standards to their self-descriptions. As self-concept develops, so does self-esteem. In addition to the academic, social, appearance, and physical/athletic dimensions of self-esteem in middle and late childhood, teens also add perceptions of their competency in romantic relationships, on the job, and in close friendships (Harter, 2006).

Contrary to popular belief, there is no empirical evidence for a significant drop in self-esteem throughout adolescence. “Barometric self-esteem” fluctuates rapidly and can cause severe distress and anxiety, but baseline self-esteem remains highly stable across adolescence. The validity of global self-esteem scales has been questioned, and many suggest that more specific scales might reveal more about the adolescent experience.

Self-esteem often decreases when children transition from one school setting to another, such as shifting from elementary to middle school, or junior high to high school (Ryan, Shim, & Makara, 2013). These decreases are usually temporary unless there are additional stressors such as parental conflict, or other family disruptions (De Wit, Karioja, Rye, & Shain, 2011). Self-esteem rises from mid to late adolescence for most teenagers, especially if they feel confident in their peer relationships, their appearance, and athletic abilities (Birkeland, Melkivik, Holsen, & Wold, 2012).

There are several self-concepts and situational factors that tend to impact an adolescent’s self-esteem. Teens that are close to their parents and their parents are authoritative tend to have higher self-esteem. Further, when adolescents are recognized for their successes, have set high vocational aspirations, are athletic, or feel attractive, they have higher self-esteem. Teens tend to have lower self-esteem when entering middle school, feel peer rejection, and experience academic failure. Also, adolescents that have authoritarian or permissive parents, need to relocate, or have low socioeconomic status, are more likely to experience lower self-esteem.

Girls are most likely to enjoy high self-esteem when engaged in supportive relationships with friends; the most important function of friendship to them is having someone who can provide social and moral support. When they fail to win friends’ approval or cannot find someone with whom to share common activities and interests, in these cases, girls suffer from low self-esteem.

In contrast, boys are more concerned with establishing and asserting their independence and defining their relation to authority. As such, they are more likely to derive high self-esteem from their ability to influence their friends. On the other hand, the lack of romantic competence, for example, failure to win or maintain the affection of a romantic interest is the major contributor to low self-esteem in adolescent boys.

Self Esteem Types

According to Mruk (2003), self-esteem is based on two factors: competence and worthiness. The relationship between competence and worthiness defines one’s self-esteem type. As these factors are a spectrum, we can even further differentiate self-esteem types and potential issues associated with each (Figure 8.1).

Figure 1. Self-Esteem meaning matrix with basic types and levels. Adapted from Mruk, 2003.

Those with high levels of competence and those that feel highly worthy will have high self-esteem. This self-esteem type tends to be stable and characterized by openness to new experiences and a tendency towards optimism. Those at the medium-high self-esteem type feel adequately competent and worthy. At the authentic level, individuals are realistic about their competence and feel worthy. They will actively pursue a life of positive, intrinsic values.

Individuals with low levels of competence and worthiness will have low self-esteem. At the negativistic level, people tend to be cautious and are protective of what little self-esteem that they do possess. Those at the classic low self-esteem level experienced impaired function due to their low feelings of competence and worth and are at risk for depression and giving up.

It is also possible to have high levels of competence but feel unworthy. This combination is a defensive or fragile self-esteem type, called competence-based self-esteem, where the person tends to compensate for their low levels of worthiness by focusing on their competence. At the success-seeking level, these individuals’ self-esteem is contingent on their achievements, and they are often anxious about failure. The Antisocial level includes an exaggerated need for success and power, even as to the point of acting out aggressively to achieve it.

The combination of low competence and high worthiness is worthiness-based self-esteem. This type is another defensive or fragile self-esteem where the individual has a low level of competence and compensates by focusing instead on their worthiness. At the approval-seeking level, these individuals are sensitive to criticism and rejection and base their self-esteem on the approval of others. At the narcissistic level, people will have an exaggerated sense of self-worth regardless of the lack of competencies. They also tend to be highly reactive to criticism and are very defensive.

Multiple Selves

Early in adolescence, cognitive developments result in greater self-awareness, greater awareness of others and their thoughts and judgments, the ability to think about abstract, future possibilities, and the ability to consider multiple possibilities at once. As a result, adolescents experience a significant shift from the simple, concrete, and global self-descriptions typical of young children; as children, they defined themselves by physical traits, whereas adolescents define themselves based on their values, thoughts, and opinions.

Adolescents can conceptualize multiple “possible selves” that they could become and long-term possibilities and consequences of their choices. Exploring these possibilities may result in abrupt changes in self-presentation as the adolescent chooses or rejects qualities and behaviors, trying to guide the actual self toward the ideal self (whom the adolescent wishes to be) and away from the feared self (whom the adolescent does not want to be). For many, these distinctions are uncomfortable, but they also appear to motivate achievement through behavior consistent with the ideal and distinct from the feared possible selves.

Further distinctions in self-concept, called “differentiation,” occur as the adolescent recognizes the contextual influences on their behavior and the perceptions of others, and begins to qualify their traits when asked to describe themselves. Differentiation appears fully developed by mid-adolescence. Peaking in the 7th-9th grades, the personality traits adolescents use to describe themselves refer to specific contexts, and therefore may contradict one another. The recognition of inconsistent content in the self-concept is a common source of distress in these years, but this distress may benefit adolescents by encouraging structural development.