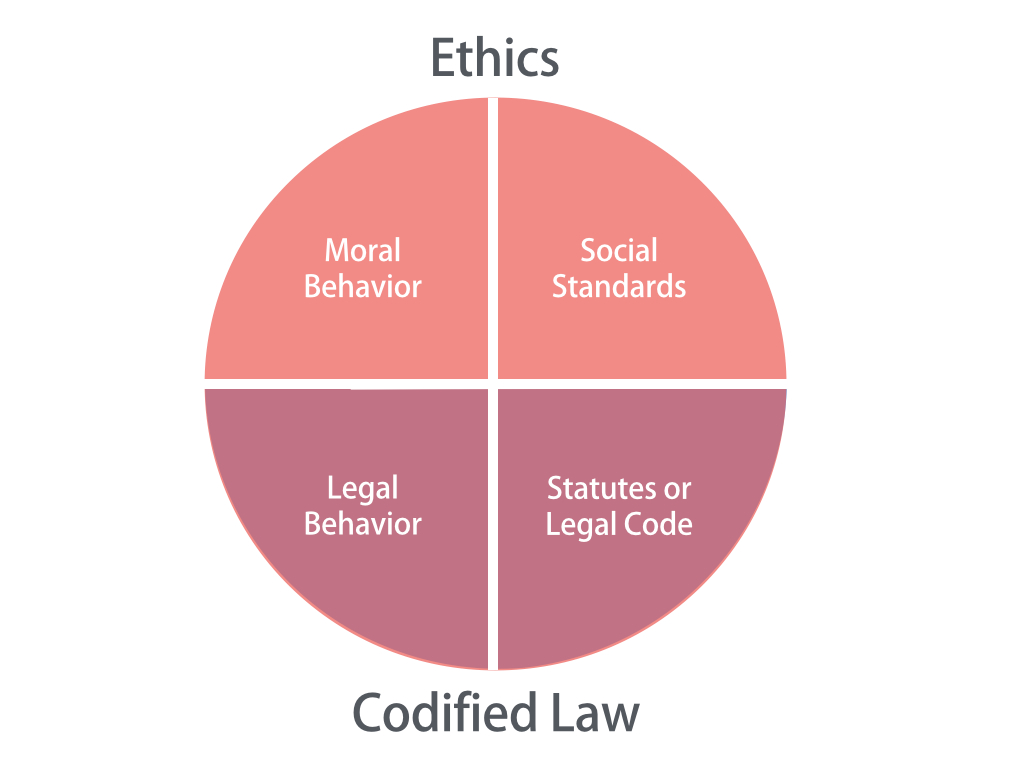

Ethics can play a significant role in healthcare decision making. Ethics can guide healthcare workers in making decisions for which there is no codified law.

CC-BY by Vivian Todhunter/CAST.

Alternative version

Ethics and Bioethics

Ethics is the code of moral principles and values that provide standards for good and bad behavior. Behavior is prescribed by social standards or moral values, and ethics comprise the shared standards of moral behavior that guide an individual or company. A decision that is ethical is both socially and morally acceptable to the community.

Closely related is the concept of biomedical ethics, or bioethics, which is the application of ethical principles to decisions in healthcare and medicine. Sometimes these decisions can have life-or-death consequences. [1] [2] For example, technological advances in medicine have led to many questions about the ethics of using technology to prolong life artificially. In one case, a widow without an advance directive suffered a severe stroke and was put on a ventilator. Her children and the medical team had to determine whether it was appropriate to apply life-sustaining measures if there was little possibility that the effects of the stroke could be reversed. [3]

Codified Law

How do ethics differ from codified law? Codified law represents the statutes or legal code adopted by a state or nation, such as the US legal code. With codified law, values and appropriate behaviors are written into the legal system and can be enforced through the court system. As such, appropriate behavior is prescribed by law. Ethical standards, on the other hand, are not codified, and people sometimes confuse ethical behavior with legal behavior.

Several states, for example, have passed laws limiting the amount and type of gifts physicians and other healthcare practitioners can receive from pharmaceutical and medical device companies. Because of the laws, there are legal consequences for healthcare practitioners who accept gifts such as free trips from companies whose goal is to expand the use of a certain drug or medical device. These state laws resulted from questions about the ethics of such gifts. [4]

In states that have no laws limiting gifts to physicians from pharmaceutical companies, the legality of such gifts is not in question. Nevertheless, accepting such gifts may be considered unethical behavior by many physicians.

Ethical Dilemma

An ethical dilemma is a decision in which each alternative has some undesirable consequence, and right or wrong cannot be clearly identified.

The Hippocratic Oath, an oath historically taken by physicians and other healthcare professionals, implies that healthcare professionals will make choices that benefit patients and will protect others from harm. However, medical care decisions often represent a conflict between what the health professional considers is in the best interest of the patient and respect for the patient’s wishes.

Care decisions can also involve a conflict between the needs of the individual and the organization or between the organization and society. For instance, a hospital’s decision to move to another area may be beneficial to the hospital’s profitability, but it may have negative consequences for access to care and the economic well-being of the community.

According to information provided to patients at the Cleveland Clinic, some common ethical questions about patient care include the following:

- When should life-sustaining treatments such as breathing machines and feeding tubes be started, continued, or stopped?

- What should family members and healthcare professionals do if a patient refuses treatment that promises to be medically helpful?

- Who should make healthcare decisions for patients when they are unable to communicate or decide for themselves?

- What should patients do when they do not understand what professionals are saying and feel they are not offered the opportunity to participate in their own healthcare decisions? [5]

Four approaches to ethical decision making are the utilitarianism, individualism, moral rights, and justice approaches. Understanding which approach is being used can help clarify the values and norms of the person or group making an ethical decision.

CC-BY by Vivian Todhunter/CAST.

Alternative version

Utilitarian Approach

Under utilitarianism, moral behavior results in the greatest good for the greatest number of people. A decision maker is expected to consider the effect of each alternative on all parties and to choose the alternative that results in the greatest satisfaction for most people. An example of the utilitarianism approach is the decision to police people’s smoking behavior in closed environments for public health reasons.

Individualistic Approach

Under individualism, decisions are moral when they promote the individual’s best long-term interests. The action to pursue is the one that produces the greatest ratio of good to bad for the individual.

With everyone pursuing their own self-interest, the greater good is served as people accommodate each other in seeking their own long-term interest. For example, lying and cheating for immediate gain will cause others to lie and cheat in return. Individualism is expected to lead to behaviors that fit standards of conduct that people want toward themselves.

Moral Rights Approach

According to the moral rights approach, human beings have fundamental rights and liberties. Therefore, any ethically correct decision respects the rights of those people affected by it. Fundamental rights include rights to privacy, free speech, due process, freedom of conscience, free consent, and health and safety. For example, the right to free consent requires informed consent before any medical treatment. Informed consent requires that health professionals provide adequate information to patients so that the patients can make informed decisions about what is best for them. Effective communication is critical in ensuring informed consent.

Justice Approach

Under the justice approach, decisions must be based on standards of equity, fairness, and impartiality. Two types of justice are distributive justice and procedural justice. According to distributive justice, individuals who are similar in respects that are relevant to a decision should not be treated differently. For example, men and women should not receive different salaries if they are doing the same job. In procedural justice, rules have to be administered fairly. That is, rules need to be clearly stated and consistently applied. One example in which the justice principle might apply is in determining which patients, out of the many patients on a waiting list, should receive organ transplants.

Medical Ethics Committees

Modern healthcare organizations establish medical ethics committees to address complex ethical decisions. These interdisciplinary teams exercise their role through education, policy, and case consultation. Medical ethics committees generally consist of an interdisciplinary group of nurses, physicians, social workers, and chaplains.

The rapid growth of medical ethics committees came after legal cases such as the 1976 Quinlan case on the removal of life-support measures. Karen Ann Quinlan, a 21-year-old New Jersey woman, lapsed into a coma and was determined by her physicians to be in a persistent vegetative state without hope of revival. In a case that went to the New Jersey State Supreme Court, her parents sued to be able to have doctors remove her ventilator tube, which her father said was causing her pain. The court ruled that Quinlan’s right to privacy exceeded the right of the state to keep her alive, and the tube was removed. Quinlan’s father decided that she was not suffering from her feeding tube, which was not removed. Karen Ann Quinlan lived for another five years. [6]

CC-BY by Vivian Todhunter/CAST.

Alternative version

Ethics Committee Role

Medical ethics committees serve primarily in three areas:

- Education: The committee provides information on ethical questions, such as workshops on withdrawing life support.

- Policy: The committee proposes, analyzes, and reviews institutional policies on difficult ethical issues.

- Case consultation: The committee reviews difficult ethical cases and makes recommendations on alternative courses of action.

References

- Health IT Workforce Curriculum, Version 3.0 (2012). Component 16, Professionalism and Customer Service in the Health Environment.Unit 8a, Ethical and Cultural Issues Related to Communication and Customer Service. This material, Comp16_Unit8a, was developed by the University of Alabama at Birmingham, funded by the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology under Award Number IU24OC000023. www.onc-ntdc.info/units/16.

- Daft, R. L. (2008). Management. South-Western Cengage Learning. Mason, OH.

- Nanos, J. (2008). Can One Sibling Pull the Plug If the Others Don’t Want To?. New York Magazine. http://nymag.com/health/bestdoctors/2008/47568/.

- Grande, D. (2009). “Limiting the Influence of Pharmaceutical Industry Gifts on Physicians: Self-Regulation or Government Intervention?.” Journal of General Internal Medicine. Volume 24. 79–83 Pages. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2811591/.

- Cleveland Clinic Health Library (2013). Dealing with Ethical Questions in Health Care.http://my.clevelandclinic.org/healthy_living/healthcare/hic_dealing_with_ethical_questions_in_health_care.aspx.

- McFadden, R. (1985). “Karen Ann Quinlan, 31, Dies; Focus of ’76 Right-to-Die Case.” New York Times. www.nytimes.com/1985/06/12/nyregion/karen-ann-quinlan-31-dies-focus-of-76-right-to-die-case.html.