Learning Objectives

- Explain the research process

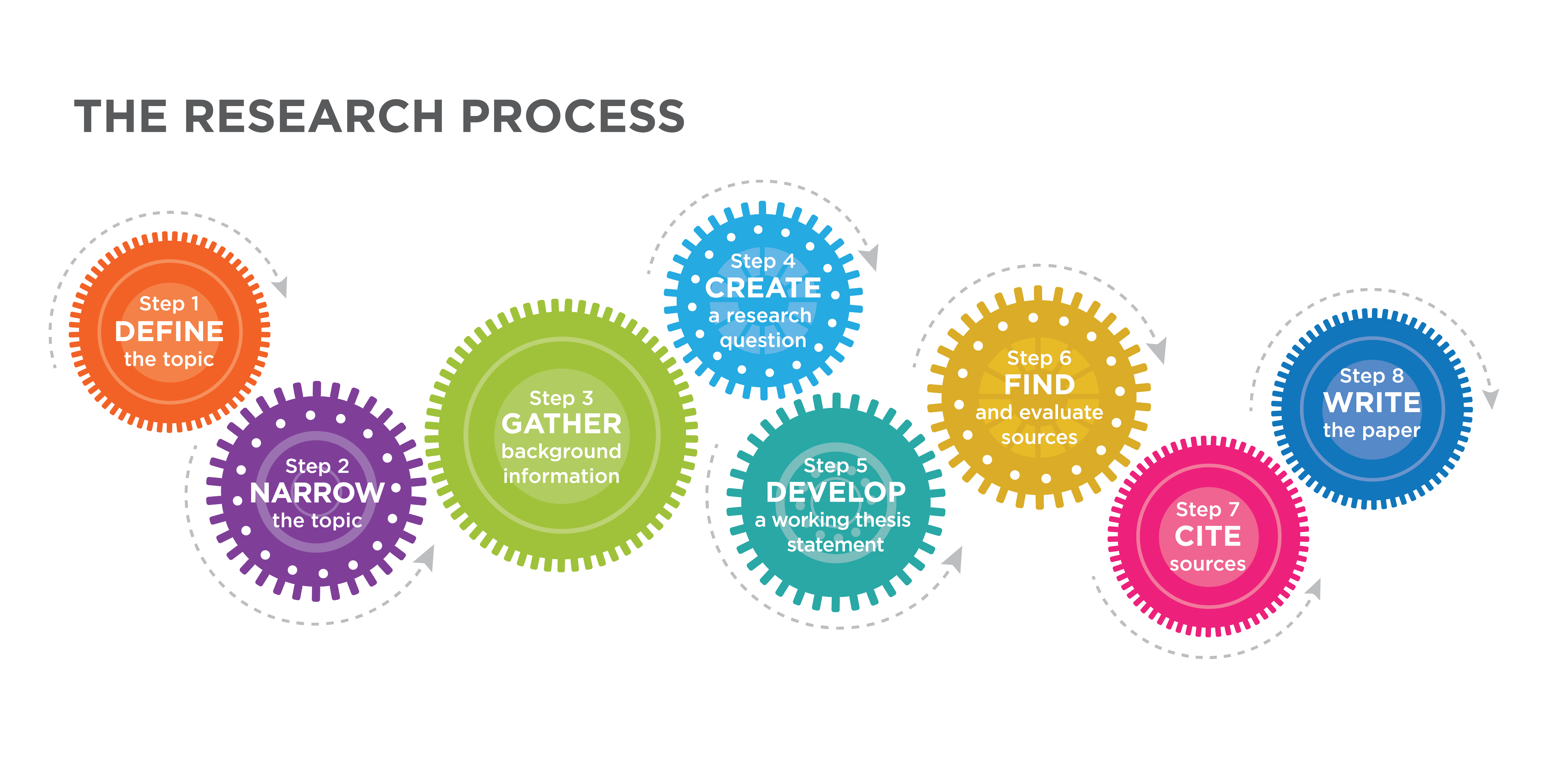

The Research Process

Figure 1. Although there is a suggested and maybe even logical sequence of steps in the Research Process, don’t feel the need to completely finish one step before moving on to the next. As you gain more experience and practice, these steps will become more fluid and flexible.

The research process is not a linear process in which you must complete step one before moving on to step two or three. You don’t need to put off writing your paper until you’ve gathered all of your sources, in fact, you may want to start writing as soon as possible and adjust your search, thesis statement, and writing as you continue to work through the research process. For that reason, consider the following research process as a guideline to follow as your work through your paper. You can (and should!) revisit the steps as many times as needed to create a finished product.

- Decide on the topic, or carefully consider the topic that has been assigned.

- Narrow the topic in order to narrow search parameters. When you go to a professional sports event, concert, or event at a large venue, your ticket has three items on it: the section, the row, and the seat number. You go in that specific order to pinpoint where you are supposed to sit. Similarly, when you decide on a topic, you often start large and must narrow the focus; you move from a general subject, to a more limited topic, to a specific focus or issue. The reader does not want a cursory look at the topic; they want to walk away with some newfound knowledge and deeper understanding of the issue. For that, details are essential. For example, suppose you want to explore the topic of autism. You might move from:

- General topic: special needs in a classroom

- Limited topic: autistic students in a classroom setting

- Specific focus: how technology can enhance learning for autistic students

- Do background research, or pre-research. Begin by figuring out what you know about the topic, and then fill in any gaps you may have on the basics by looking at more general sources. This is a place where general Google searches, Wikipedia, or another encyclopedia-style source will be most useful. Once you know the basics of the topic, start investigating that basic information for potential sources of conflict. Does there seem to be disagreement about particular aspects of the topic? For instance, if you are reading about a war, are there any parts of the battle that historians seem to argue about in their interpretations of what happened?

- Create a research question. Once you have narrowed your topic so that it is manageable, it is then time to generate research questions about your topic. Create thought-provoking, open-ended questions, ones that encourage debate. Decide which question addresses the issue that concerns you—that will be your main research question. Secondary questions will address the who, what, when, where, why, and how of the issue. As an example:

- Main question: Do media depictions of women show their strengths or weaknesses as political leaders?

- Secondary questions: How can more women get involved in leadership roles? Why aren’t more women involved in politics? What role do media play in discouraging women from being involved? How many women are involved in politics at a state or national level? How long do they typically stay in politics, and for what reasons do they leave?

- Next, “answer” the main research question to create a working thesis statement. The thesis statement is a single sentence that identifies the topic and shows the direction of the paper while simultaneously allowing the reader to glean the writer’s stance on that topic. A working thesis performs four main functions:

- Narrows the subject to the single point that readers should understand

- Names the topic and makes a significant assertion about that topic

- Conveys the purpose

- Provides a preview of how the essay will be arranged (usually).

- Determine what kind of sources are best for your argument.

- How many sources will you need? How long should your paper be? Will you need primary or secondary sources? Where will you find the best information?

- Create a bibliography as you gather and reference sources. Make sure you are using credible and relevant sources. It’s always a good idea to utilize reference management programs like Zotero, Mendeley, or EndNote so you can keep track of your research and citations while you are working and searching, instead of waiting until the end.

- Write and edit your paper! Finally, you’ll incorporate the research into your own writing and properly cite your sources.

Try It

Walking, Talking, Cooking, and Eating

Next we’ll examine the research writing process through the example of Marvin, a student at Any College who gets advice from an online professor on writing his research paper. You’ll read bits and pieces of their dialogue throughout the module and come to understand how the research writing process can be compared to walking, talking, cooking, and eating. In the following dialogue, consider the professor’s recommendations to Marvin about how to think more deeply about his assignment and what angle to take for his paper. Just like Martin, you should begin your research by thinking about the importance of your topic and what about it you find interesting. It also helps to talk with someone about your paper, whether that be a friend, family member, classmate, teaching assistant, librarian, or professor.

Getting Started: Walking to Sources

Marvin, a college student at Any College, sits down at his computer. He logs in to the “Online Professor (O-Prof),” an interactive advice site for students. After setting up a chat, he begins tapping the keys.

Marvin: Hi. I’m a student in the physician assistant program. The major paper for my health and environment class is due in five weeks, and I need some advice. The professor says the paper has to be 6–8 pages, and I have to cite and document my sources.

O-Prof: Congratulations on getting started early! Tell me a bit about your assignment. What’s the purpose? Who’s it intended for?

Marvin: Well, the professor said it should talk about a health problem caused by water pollution and suggest ways to solve it. We’ve read some articles, plus my professor gave us statistics on groundwater contamination in different areas.

O-Prof: What’s been most interesting so far?

Marvin: I’m amazed at how much water pollution there is. It seems like it would be healthier to drink bottled water, but the plastic bottles hurt the environment.

O-Prof: Who else might be interested in this?

Marvin: Lots of people are worried about bad water. I might even get questions about it from my clients once I finish my program.

O-Prof: OK. So what information do you need to make a good recommendation?

Marvin thinks for a moment.

Marvin: I don’t know much about the health problems caused by contaminated drinking water. Whether the tap water is safe depends on where you live, I guess. The professors talked about arsenic poisoning in Bangladesh, but what about the water in the U.S.? For my paper, maybe I should focus on a particular location? I also need to find out more about what companies do to make sure bottled water is pure.

O-Prof: Good! Now that you know what you need to learn, you can start looking for sources.

Marvin: When my professors talk about sources, they usually mean books or articles about my topic. Is that what you mean?

O-Prof: Books and articles do make good sources, but you might think about sources more generally as “forms of meaning you use to make new meaning.” It’s like your bottled water. The water exists already in some location but is processed by the company before it goes to the consumer. Similarly, a source provides information and knowledge that you process to produce new meaning, which other people can then use to make their own meaning.

A bit confused, Marvin scratches his head.

Marvin: I thought I knew what a source was, but now I’m not so sure.

O-Prof: Think about it. Sources of meaning are everywhere—for example, your own observations or experiences, the content of other people’s brains, visuals and graphics, experiment results, TV and radio broadcasts, and written texts. And, there are many ways to make new meaning from sources. You can give an oral presentation, design a web page, paint a picture, or write a paper.

Marvin: I get it. But how do I decide which sources to use for my paper?

O-Prof: It depends on the meaning you want to make, which is why it’s so important to figure out the purpose of your paper and who will read it. You might think about using sources as walking, talking, cooking, and eating. These aren’t the only possible metaphors, but they do capture some important things about using sources.

Marvin: Hey! I thought we were talking about writing!

O-Prof: We are, but these metaphors can shed some light on writing with sources. Let’s start with the first one: walking. To use sources well, you first have to go where they are. What if you were writing an article on student clubs for the school newspaper? Where would you go for information?

Marvin: I’d probably walk down to the Student Activities office and get some brochures about student clubs. Then I’d attend a few club meetings and maybe interview the club leaders and some members about their club activities.

O-Prof: OK, so you’d walk to where you could find relevant information for your article. That’s what I mean by walking. You have to get to the sources you need.

Marvin: Wait a minute. For the article on student clubs, maybe I could save some walking. Maybe the list of clubs and the club descriptions are on the Student Activities web page. That’d save me a trip.

O-Prof: Yes, the Internet has cut down on the amount of physical walking you need to do to find sources. Before the Internet, you had to either travel to a source’s physical location, or bring that source to your location. Think about your project on bottled water. To get information about the quality of a city’s tap water in the 1950s, you would have had to figure out who’d have that information, then call or write to request a copy or walk to wherever the information was stored. Today, if you type “local water quality” into Google, the Environmental Protection Agency page comes up as one of the first hits. Its home page links to water quality reports for local areas.

Marvin pauses for a second before responding, thinking he’s found a good short cut for his paper.

To be continued. . .

Try It