Types of Unemployment

Workers may find themselves unemployed for different reasons. Each source of unemployment has quite different implications, not only for the workers it affects but also for public policy.

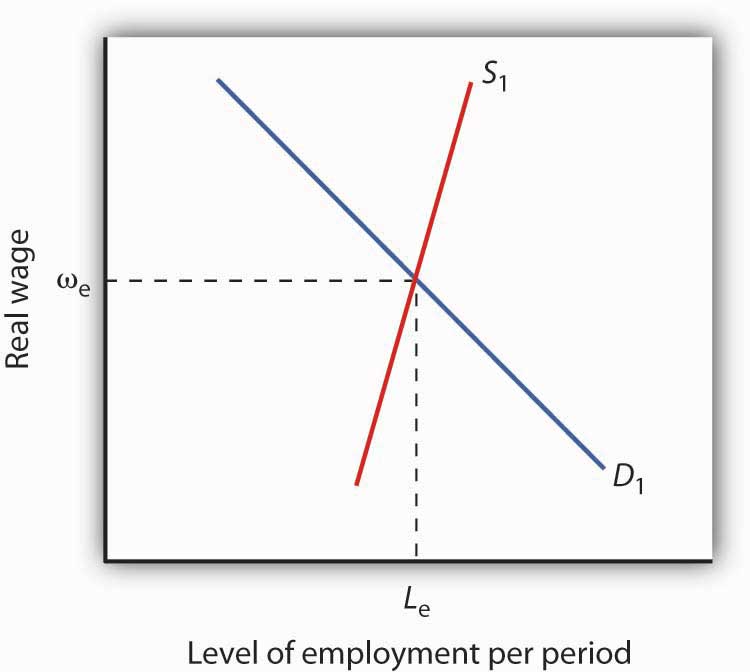

Figure 5.9 “The Natural Level of Employment” applies the demand and supply model to the labor market. The price of labor is taken as the real wage, which is the nominal wage divided by the price level; the symbol used to represent the real wage is the Greek letter omega, ω. The supply curve is drawn as upward sloping, though steep, to reflect studies showing that the quantity of labor supplied at any one time is nearly fixed. Thus, an increase in the real wage induces a relatively small increase in the quantity of labor supplied. The demand curve shows the quantity of labor demanded at each real wage. The lower the real wage, the greater the quantity of labor firms will demand. In the case shown here, the real wage, ωe, equals the equilibrium solution defined by the intersection of the demand curve D1 and the supply curve S1. The quantity of labor demanded, Le, equals the quantity supplied. The employment level at which the quantity of labor demanded equals the quantity supplied is called the natural level of employment. It is sometimes referred to as full employment.

Figure 5.9 The Natural Level of Employment. The employment level at which the quantity of labor demanded equals the quantity supplied is called the natural level of employment. Here, the natural level of employment is Le, which is achieved at a real wage ωe.

Even if the economy is operating at its natural level of employment, there will still be some unemployment. The rate of unemployment consistent with the natural level of employment is called the natural rate of unemployment. Business cycles may generate additional unemployment. We discuss these various sources of unemployment below.

Frictional Unemployment

Even when the quantity of labor demanded equals the quantity of labor supplied, not all employers and potential workers have found each other. Some workers are looking for jobs, and some employers are looking for workers. During the time it takes to match them up, the workers are unemployed. Unemployment that occurs because it takes time for employers and workers to find each other is called frictional unemployment.

The case of college graduates engaged in job searches is a good example of frictional unemployment. Those who did not land a job while still in school will seek work. Most of them will find jobs, but it will take time. During that time, these new graduates will be unemployed. If information about the labor market were costless, firms and potential workers would instantly know everything they needed to know about each other and there would be no need for searches on the part of workers and firms. There would be no frictional unemployment. But information is costly. Job searches are needed to produce this information, and frictional unemployment exists while the searches continue.

The government may attempt to reduce frictional unemployment by focusing on its source: information costs. Many state agencies, for example, serve as clearinghouses for job market information. They encourage firms seeking workers and workers seeking jobs to register with them. To the extent that such efforts make labor-market information more readily available, they reduce frictional unemployment.

Structural Unemployment

Another reason there can be unemployment even if employment equals its natural level stems from potential mismatches between the skills employers seek and the skills potential workers offer. Every worker is different; every job has its special characteristics and requirements. The qualifications of job seekers may not match those that firms require. Even if the number of employees firms demand equals the number of workers available, people whose qualifications do not satisfy what firms are seeking will find themselves without work. Unemployment that results from a mismatch between worker qualifications and the characteristics employers require is called structural unemployment.

Structural unemployment emerges for several reasons. Technological change may make some skills obsolete or require new ones. The widespread introduction of personal computers since the 1980s, for example, has lowered demand for typists who lacked computer skills.

Structural unemployment can occur if too many or too few workers seek training or education that matches job requirements. Students cannot predict precisely how many jobs there will be in a particular category when they graduate, and they are not likely to know how many of their fellow students are training for these jobs. Structural unemployment can easily occur if students guess wrong about how many workers will be needed or how many will be supplied.

Structural unemployment can also result from geographical mismatches. Economic activity may be booming in one region and slumping in another. It will take time for unemployed workers to relocate and find new jobs. And poor or costly transportation may block some urban residents from obtaining jobs only a few miles away.

Public policy responses to structural unemployment generally focus on job training and education to equip workers with the skills firms demand. The government publishes regional labor-market information, helping to inform unemployed workers of where jobs can be found. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which created a free trade region encompassing Mexico, the United States, and Canada, has created some structural unemployment in the three countries. In the United States, the legislation authorizing the pact also provided for job training programs for displaced U.S. workers.

Although government programs may reduce frictional and structural unemployment, they cannot eliminate it. Information in the labor market will always have a cost, and that cost creates frictional unemployment. An economy with changing demands for goods and services, changing technology, and changing production costs will always have some sectors expanding and others contracting—structural unemployment is inevitable. An economy at its natural level of employment will therefore have frictional and structural unemployment.

Cyclical Unemployment

Of course, the economy may not be operating at its natural level of employment, so unemployment may be above or below its natural level. In a later chapter we will explore what happens when the economy generates employment greater or less than the natural level. Cyclical unemployment is unemployment in excess of the unemployment that exists at the natural level of employment.

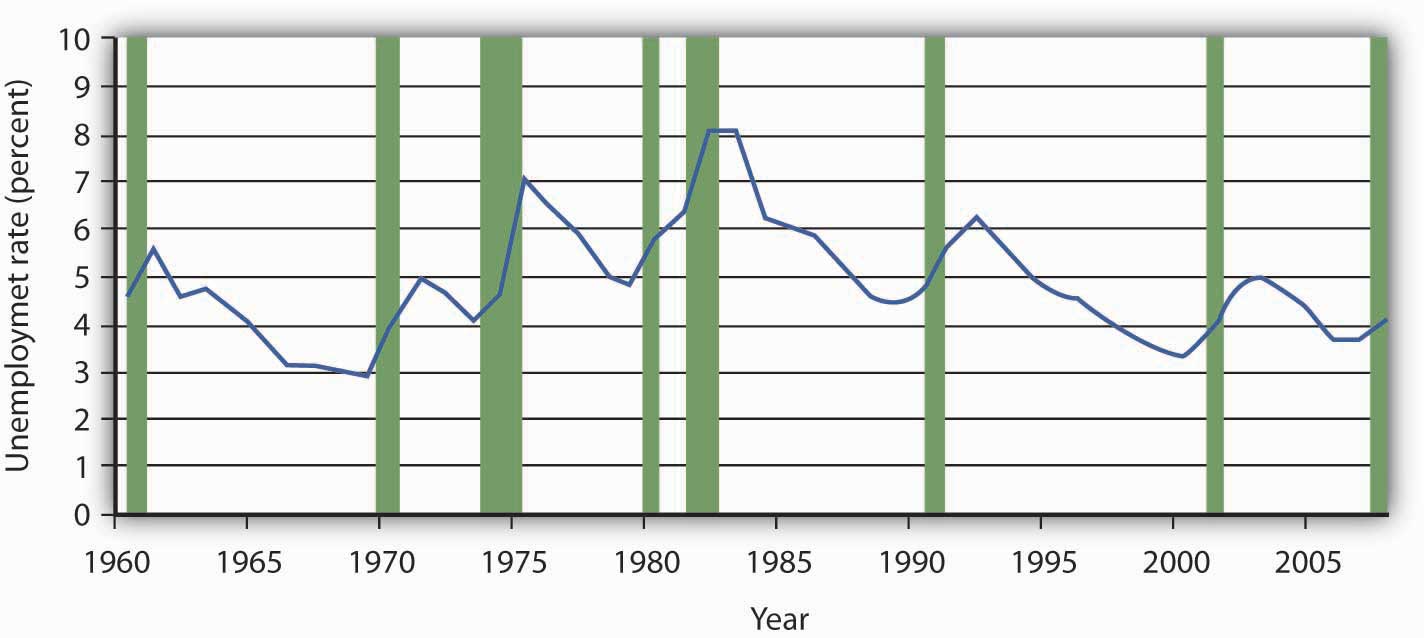

Figure 5.10 “Unemployment Rate, 1960–2008” shows the unemployment rate in the United States for the period from 1960 through October 2008. We see that it has fluctuated considerably. How much of it corresponds to the natural rate of unemployment varies over time with changing circumstances. For example, in a country with a demographic “bulge” of new entrants into the labor force, frictional unemployment is likely to be high, because it takes the new entrants some time to find their first jobs. This factor alone would raise the natural rate of unemployment. A demographic shift toward more mature workers would lower the natural rate. During recessions, highlighted in Figure 5.10 “Unemployment Rate, 1960–2008,” the part of unemployment that is cyclical unemployment grows. The analysis of fluctuations in the unemployment rate, and the government’s responses to them, are an important macroeconomic topic that will recur throughout this course.

Figure 5.10 Unemployment Rate, 1960–2008. The chart shows the unemployment rate for each year from 1960 to 2008. Recessions are shown as shaded areas. Source: Economic Report of the President, 2008, Table B-42. Date for 2008 is average of first ten months from the Bureau of Labor Statistics home page.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- People who are not working but are looking and available for work at any one time are considered unemployed. The unemployment rate is the percentage of the labor force that is unemployed.

- When the labor market is in equilibrium, employment is at the natural level and the unemployment rate equals the natural rate of unemployment.

- Even if employment is at the natural level, the economy will experience frictional and structural unemployment. Cyclical unemployment is unemployment in excess of that associated with the natural level of employment.

Candela Citations

- Principles of Macroeconomics Chapter 5.3. Authored by: Anonymous. Located at: http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/macroeconomics-principles-v1.0/s08-03-unemployment.html. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike