The Building Blocks of Keynesian Analysis

Now that we have a clear understanding of what constitutes aggregate demand, we return to the Keynesian argument using the model of aggregate supply and aggregate demand (AS–AD).

Keynesian economics focuses on explaining why recessions and depressions occur and offering a policy prescription for minimizing their effects. The Keynesian view of recession is based on two key building blocks. First, aggregate demand is not always automatically high enough to provide firms with an incentive to hire enough workers to reach full employment. Second, the macroeconomy may adjust only slowly to shifts in aggregate demand because of sticky wages and prices, which are wages and prices that do not respond to decreases or increases in demand. We will consider these two claims in turn, and then see how they are represented in the AS–AD model.

The first building block of the Keynesian diagnosis is that recessions occur when the level of household and business sector demand for goods and services is less than what is produced when labor is fully employed. In other words, the intersection of aggregate supply and aggregate demand occurs at a level of output less than the level of GDP consistent with full employment. Suppose the stock market crashes, as occurred in 1929. Or, suppose the housing market collapses, as occurred in 2008. In either case, household wealth will decline, and consumption expenditure will follow. Suppose businesses see that consumer spending is falling. That will reduce expectations of the profitability of investment, so businesses will decrease investment expenditure.This seemed to be the case during the Great Depression, since the physical capacity of the economy to supply goods did not alter much. No flood or earthquake or other natural disaster ruined factories in 1929 or 1930. No outbreak of disease decimated the ranks of workers. No key input price, like the price of oil, soared on world markets.

The U.S. economy in 1933 had just about the same factories, workers, and state of technology as it had had four years earlier in 1929—and yet the economy had shrunk dramatically. This also seems to be what happened in 2008. As Keynes recognized, the events of the Depression contradicted Say’s law that “supply creates its own demand.” Although production capacity existed, the markets were not able to sell their products. As a result, real GDP was less than potential GDP.

LINK IT UP

Visit this website for raw data used to calculate GDP.

Wage and Price Stickiness

Keynes also pointed out that although AD fluctuated, prices and wages did not immediately respond as economists often expected. Instead, prices and wages are “sticky,” making it difficult to restore the economy to full employment and potential GDP. Keynes emphasized one particular reason why wages were sticky: the coordination argument. This argument points out that, even if most people would be willing—at least hypothetically—to see a decline in their own wages in bad economic times as long as everyone else also experienced such a decline, a market-oriented economy has no obvious way to implement a plan of coordinated wage reductions. Unemployment proposed a number of reasons why wages might be sticky downward, most of which center on the argument that businesses avoid wage cuts because they may in one way or another depress morale and hurt the productivity of the existing workers.

Some modern economists have argued in a Keynesian spirit that, along with wages, other prices may be sticky, too. Many firms do not change their prices every day or even every month. When a firm considers changing prices, it must consider two sets of costs. First, changing prices uses company resources: managers must analyze the competition and market demand and decide what the new prices will be, sales materials must be updated, billing records will change, and product labels and price labels must be redone. Second, frequent price changes may leave customers confused or angry—especially if they find out that a product now costs more than expected. These costs of changing prices are called menu costs—like the costs of printing up a new set of menus with different prices in a restaurant. Prices do respond to forces of supply and demand, but from a macroeconomic perspective, the process of changing all prices throughout the economy takes time.

To understand the effect of sticky wages and prices in the economy, consider Figure 11.4 (a) illustrating the overall labor market, while Figure 11.4 (b) illustrates a market for a specific good or service. The original equilibrium (E0) in each market occurs at the intersection of the demand curve (D0) and supply curve (S0). When aggregate demand declines, the demand for labor shifts to the left (to D1) in Figure 11.4 (a) and the demand for goods shifts to the left (to D1) in Figure 11.4 (b). However, because of sticky wages and prices, the wage remains at its original level (W0) for a period of time and the price remains at its original level (P0).

As a result, a situation of excess supply—where the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded at the existing wage or price—exists in markets for both labor and goods, and Q1 is less than Q0 in both Figure 11.4 (a) and Figure 11.4 (b). When many labor markets and many goods markets all across the economy find themselves in this position, the economy is in a recession; that is, firms cannot sell what they wish to produce at the existing market price and do not wish to hire all who are willing to work at the existing market wage. The Clear It Up feature about the pace of wage adjustments discusses this problem in more detail.

Figure 11. 4. Sticky Prices and Falling Demand in the Labor and Goods Market. In both (a) and (b), demand shifts left from D0 to D1. However, the wage in (a) and the price in (b) do not immediately decline. In (a), the quantity demanded of labor at the original wage (W0) is Q0, but with the new demand curve for labor (D1), it will be Q1. Similarly, in (b), the quantity demanded of goods at the original price (P0) is Q0, but at the new demand curve (D1) it will be Q1. An excess supply of labor will exist, which is called unemployment. An excess supply of goods will also exist, where the quantity demanded is substantially less than the quantity supplied. Thus, sticky wages and sticky prices, combined with a drop in demand, bring about unemployment and recession.

WHY IS THE PACE OF WAGE ADJUSTMENTS SLOW?

The recovery after the Great Recession in the United States has been slow, with wages stagnant, if not declining. In fact, many low-wage workers at McDonalds, Dominos, and Walmart have threatened to strike for higher wages. Their plight is part of a larger trend in job growth and pay in the post–recession recovery.

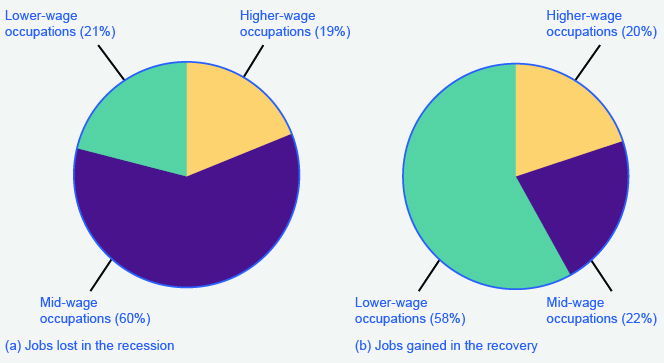

Figure 11.5. Jobs Lost/Gained in the Recession/Recovery. Data in the aftermath of the Great Recession suggests that jobs lost were in mid-wage occupations, while jobs gained were in low-wage occupations.

The National Employment Law Project compiled data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and found that, during the Great Recession, 60% of job losses were in medium-wage occupations. Most of them were replaced during the recovery period with lower-wage jobs in the service, retail, and food industries. This data is illustrated in Figure 11.5.

Wages in the service, retail, and food industries are at or near minimum wage and tend to be both downwardly and upwardly “sticky.” Wages are downwardly sticky due to minimum wage laws; they may be upwardly sticky if insufficient competition in low-skilled labor markets enables employers to avoid raising wages that would reduce their profits. At the same time, however, the Consumer Price Index increased 11% between 2007 and 2012, pushing real wages down.

The Two Keynesian Assumptions in the AS–AD Model

These two Keynesian assumptions—the importance of aggregate demand in causing recession and the stickiness of wages and prices—are illustrated by the AS–AD diagram in Figure 11.6. Note that because of the stickiness of wages and prices, the aggregate supply curve is flatter than either supply curve (labor or specific good). In fact, if wages and prices were so sticky that they did not fall at all, the aggregate supply curve would be completely flat below potential GDP, as shown in Figure 11.6. This outcome is an important example of a macroeconomic externality, where what happens at the macro level is different from the sum of what happens at the micro level.

The original equilibrium of this economy occurs where the aggregate demand function (AD0) intersects with AS. Since this intersection occurs at potential GDP (Yp), the economy is operating at full employment. When aggregate demand shifts to the left, all the adjustment occurs through decreased real GDP. There is no decrease in the price level. Since the equilibrium occurs at Y1, the economy experiences substantial unemployment.

Figure 11.6. A Keynesian Perspective of Recession. The equilibrium (E0) illustrates the two key assumptions behind Keynesian economics. The importance of aggregate demand is shown because this equilibrium is a recession which has occurred because aggregate demand is at AD1 instead of AD0. The importance of sticky wages and prices is shown because of the assumption of fixed wages and prices, which make the AS curve flat below potential GDP. Thus, when AD falls, the intersection E1 occurs in the flat portion of the AS curve where the price level does not change.

Candela Citations

- Principles of Macroeconomics Chapter 12.2. Authored by: OpenStax College. Provided by: Rice University. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/4061c832-098e-4b3c-a1d9-7eb593a2cb31@10.49:2/Macroeconomics. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/donate/download/4061c832-098e-4b3c-a1d9-7eb593a2cb31@10.49/pdf