The Baroque-Classical Transition c. 1730–1760

Gluck, detail of a portrait by Joseph Duplessis, dated 1775 (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

At first the new style took over baroque forms—the ternary da capo aria and the sinfonia and concerto—but composed with simpler parts, more notated ornamentation and more emphatic division into sections. However, over time, the new aesthetic caused radical changes in how pieces were put together, and the basic layouts changed. Composers from this period sought dramatic effects, striking melodies, and clearer textures. The Italian composer Domenico Scarlatti was an important figure in the transition from baroque to classical. His unique compositional style is strongly related to that of the early classical period. He is best known for composing more than five hundred one-movement keyboard sonatas. In Spain,Antonio Soler also produced valuable keyboard sonatas, more varied in form than those of Scarlatti, with some pieces in three or four movements.

Baroque music generally uses many harmonic fantasies and does not concentrate that much on the structure of the musical piece, musical phrases and motives. In the classical period, the harmonic functions are simpler. However, the structure of the piece, the phrases and motives, are much more important in the tunes than in the baroque period.

Another important break with the past was the radical overhaul of opera by Christoph Willibald Gluck, who cut away a great deal of the layering and improvisational ornament and focused on the points of modulation and transition. By making these moments where the harmony changes more focal, he enabled powerful dramatic shifts in the emotional color of the music. To highlight these episodes he used changes in instrumentation, melody, and mode. Among the most successful composers of his time, Gluck spawned many emulators, one of whom was Antonio Salieri. Their emphasis on accessibility brought huge successes in opera, and in vocal music more widely: songs, oratorios, and choruses. These were considered the most important kinds of music for performance and hence enjoyed greatest success in the public estimation.

The phase between the baroque and the rise of the classical, with its broad mixture of competing ideas and attempts to unify the different demands of taste, economics and “worldview”, goes by many names. It is sometimes called galant, rococo, or pre-classical, or at other times early classical. It is a period where some composers still working in the baroque style flourish, though sometimes thought of as being more of the past than the present—Bach, Handel, and Telemann all composed well beyond the point at which the homophonic style is clearly in the ascendant. Musical culture was caught at a crossroads: the masters of the older style had the technique, but the public hungered for the new. This is one of the reasons C. P. E. Bach was held in such high regard: he understood the older forms quite well and knew how to present them in new garb, with an enhanced variety of form.

Circa 1750–1775

Haydn portrait by Thomas Hardy, 1792

By the late 1750s there were flourishing centers of the new style in Italy, Vienna, Mannheim, and Paris; dozens of symphonies were composed and there were bands of players associated with theatres. Opera or other vocal music was the feature of most musical events, with concertos and symphonies (arising from the overture) serving as instrumental interludes and introductions for operas and church services. Over the course of the classical period, symphonies and concertos developed and were presented independently of vocal music.

The “normal” ensemble—a body of strings supplemented by winds—and movements of particular rhythmic character were established by the late 1750s in Vienna. However, the length and weight of pieces was still set with some baroque characteristics: individual movements still focused on one “affect” or had only one sharply contrasting middle section, and their length was not significantly greater than baroque movements. There was not yet a clearly enunciated theory of how to compose in the new style. It was a moment ripe for a breakthrough.

Many consider this breakthrough to have been made by C. P. E. Bach, Gluck, and several others. Indeed, C. P. E. Bach and Gluck are often considered founders of the classical style.

The first great master of the style was the composer Joseph Haydn. In the late 1750s he began composing symphonies, and by 1761 he had composed a triptych (Morning, Noon, and Evening) solidly in the contemporary mode. As a vice-Kapellmeister and later Kapellmeister, his output expanded: he composed over forty symphonies in the 1760s alone. And while his fame grew, as his orchestra was expanded and his compositions were copied and disseminated, his voice was only one among many.

While some suggest that he was overshadowed by Mozart and Beethoven, it would be difficult to overstate Haydn’s centrality to the new style, and therefore to the future of Western art music as a whole. At the time, before the pre-eminence of Mozart or Beethoven, and with Johann Sebastian Bach known primarily to connoisseurs of keyboard music, Haydn reached a place in music that set him above all other composers except perhaps George Frideric Handel. He took existing ideas, and radically altered how they functioned—earning him the titles “father of the symphony” and “father of the string quartet”.

One of the forces that worked as an impetus for his pressing forward was the first stirring of what would later be called Romanticism—the Sturm und Drang, or “storm and stress” phase in the arts, a short period where obvious emotionalism was a stylistic preference. Haydn accordingly wanted more dramatic contrast and more emotionally appealing melodies, with sharpened character and individuality. This period faded away in music and literature: however, it influenced what came afterward and would eventually be a component of aesthetic taste in later decades.

The Farewell Symphony, No. 45 in F♯ Minor, exemplifies Haydn’s integration of the differing demands of the new style, with surprising sharp turns and a long adagio to end the work. In 1772, Haydn completed his Opus 20 set of six string quartets, in which he deployed the polyphonic techniques he had gathered from the previous era to provide structural coherence capable of holding together his melodic ideas. For some, this marks the beginning of the “mature” classical style, in which the period of reaction against late baroque complexity yielded to a period of integration baroque and classical elements.

Circa 1775–1790

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, posthumous painting by Barbara Krafft in 1819

Haydn, having worked for over a decade as the music director for a prince, had far more resources and scope for composing than most and also the ability to shape the forces that would play his music. This opportunity was not wasted, as Haydn, beginning quite early on his career, sought to press forward the technique of building ideas in music. His next important breakthrough was in the Opus 33 string quartets (1781), in which the melodic and the harmonic roles segue among the instruments: it is often momentarily unclear what is melody and what is harmony. This changes the way the ensemble works its way between dramatic moments of transition and climactic sections: the music flows smoothly and without obvious interruption. He then took this integrated style and began applying it to orchestral and vocal music.

Haydn’s gift to music was a way of composing, a way of structuring works, which was at the same time in accord with the governing aesthetic of the new style. However, a younger contemporary, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, brought his genius to Haydn’s ideas and applied them to two of the major genres of the day: opera, and the virtuoso concerto. Whereas Haydn spent much of his working life as a court composer, Mozart wanted public success in the concert life of cities. This meant opera, and it meant performing as a virtuoso. Haydn was not a virtuoso at the international touring level; nor was he seeking to create operatic works that could play for many nights in front of a large audience. Mozart wanted both. Moreover, Mozart also had a taste for more chromatic chords (and greater contrasts in harmonic language generally), a greater love for creating a welter of melodies in a single work, and a more Italianate sensibility in music as a whole. He found, in Haydn’s music and later in his study of the polyphony of Bach, the means to discipline and enrich his gifts.

The Mozart family circa 1780. The portrait on the wall is of Mozart’s mother.

Mozart rapidly came to the attention of Haydn, who hailed the new composer, studied his works, and considered the younger man his only true peer in music. In Mozart, Haydn found a greater range of instrumentation, dramatic effect and melodic resource; the learning relationship moved in two directions.

Mozart’s arrival in Vienna in 1780 brought an acceleration in the development of the classical style. There Mozart absorbed the fusion of Italianate brilliance and Germanic cohesiveness that had been brewing for the previous 20 years. His own taste for brilliances, rhythmically complex melodies and figures, long cantilena melodies, and virtuoso flourishes was merged with an appreciation for formal coherence and internal connectedness. It is at this point that war and inflation halted a trend to larger orchestras and forced the disbanding or reduction of many theater orchestras. This pressed the classical style inwards: toward seeking greater ensemble and technical challenge—for example, scattering the melody across woodwinds, or using thirds to highlight the melody taken by them. This process placed a premium on chamber music for more public performance, giving a further boost to the string quartet and other small ensemble groupings.

It was during this decade that public taste began, increasingly, to recognize that Haydn and Mozart had reached a higher standard of composition. By the time Mozart arrived at age 25, in 1781, the dominant styles of Vienna were recognizably connected to the emergence in the 1750s of the early classical style. By the end of the 1780s, changes in performance practice, the relative standing of instrumental and vocal music, technical demands on musicians, and stylistic unity had become established in the composers who imitated Mozart and Haydn. During this decade Mozart composed his most famous operas, his six late symphonies that helped to redefine the genre, and a string of piano concerti that still stand at the pinnacle of these forms.

One composer who was influential in spreading the more serious style that Mozart and Haydn had formed is Muzio Clementi, a gifted virtuoso pianist who tied with Mozart in a musical “duel” before the emperor in which they each improvised and performed their compositions. Clementi’s sonatas for the piano circulated widely, and he became the most successful composer in London during the 1780s. Also in London at this time was Jan Ladislav Dussek, who, like Clementi, encouraged piano makers to extend the range and other features of their instruments, and then fully exploited the newly opened possibilities. The importance of London in the classical period is often overlooked, but it served as the home to the Broadwood’s factory for piano manufacturing and as the base for composers who, while less notable than the “Vienna School”, had a decisive influence on what came later. They were composers of many fine works, notable in their own right. London’s taste for virtuosity may well have encouraged the complex passage work and extended statements on tonic and dominant.

Circa 1790–1820

When Haydn and Mozart began composing, symphonies were played as single movements—before, between, or as interludes within other works—and many of them lasted only ten or twelve minutes; instrumental groups had varying standards of playing, and the continuo was a central part of music-making.

In the intervening years, the social world of music had seen dramatic changes. International publication and touring had grown explosively, and concert societies formed. Notation became more specific, more descriptive—and schematics for works had been simplified (yet became more varied in their exact working out). In 1790, just before Mozart’s death, with his reputation spreading rapidly, Haydn was poised for a series of successes, notably his late oratorios and “London” symphonies. Composers in Paris, Rome, and all over Germany turned to Haydn and Mozart for their ideas on form.

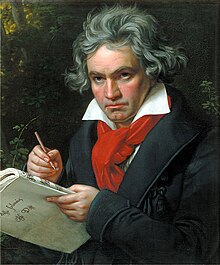

Portrait of Beethoven by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1820

The time was again ripe for a dramatic shift. In the 1790s, a new generation of composers, born around 1770, emerged. While they had grown up with the earlier styles, they heard in the recent works of Haydn and Mozart a vehicle for greater expression. In 1788 Luigi Cherubini settled in Paris and in 1791 composed Lodoiska, an opera that raised him to fame. Its style is clearly reflective of the mature Haydn and Mozart, and its instrumentation gave it a weight that had not yet been felt in the grand opera. His contemporary Étienne Méhul extended instrumental effects with his 1790 opera Euphrosine et Coradin, from which followed a series of successes.

The most fateful of the new generation was Ludwig van Beethoven, who launched his numbered works in 1794 with a set of three piano trios, which remain in the repertoire. Somewhat younger than the others, though equally accomplished because of his youthful study under Mozart and his native virtuosity, was Johann Nepomuk Hummel. Hummel studied under Haydn as well; he was a friend to Beethoven and Franz Schubert. He concentrated more on the piano than any other instrument, and his time in London in 1791 and 1792 generated the composition and publication in 1793 of three piano sonatas, opus 2, which idiomatically used Mozart’s techniques of avoiding the expected cadence, and Clementi’s sometimes modally uncertain virtuoso figuration. Taken together, these composers can be seen as the vanguard of a broad change in style and the center of music. They studied one another’s works, copied one another’s gestures in music, and on occasion behaved like quarrelsome rivals.

Hummel in 1814

The crucial differences with the previous wave can be seen in the downward shift in melodies, increasing durations of movements, the acceptance of Mozart and Haydn as paradigmatic, the greater use of keyboard resources, the shift from “vocal” writing to “pianistic” writing, the growing pull of the minor and of modal ambiguity, and the increasing importance of varying accompanying figures to bring “texture” forward as an element in music. In short, the late classical was seeking a music that was internally more complex. The growth of concert societies and amateur orchestras, marking the importance of music as part of middle-class life, contributed to a booming market for pianos, piano music, and virtuosi to serve as examplars. Hummel, Beethoven, and Clementi were all renowned for their improvising.

Direct influence of the baroque continued to fade: the figured bass grew less prominent as a means of holding performance together, the performance practices of the mid-18th century continued to die out. However, at the same time, complete editions of baroque masters began to become available, and the influence of baroque style continued to grow, particularly in the ever more expansive use of brass. Another feature of the period is the growing number of performances where the composer was not present. This led to increased detail and specificity in notation; for example, there were fewer “optional” parts that stood separately from the main score.

The force of these shifts became apparent with Beethoven’s 3rd Symphony, given the name Eroica, which is Italian for “heroic,” by the composer. As with Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, it may not have been the first in all of its innovations, but its aggressive use of every part of the classical style set it apart from its contemporary works: in length, ambition, and harmonic resources as well.

Time Line of Classical Composers

Candela Citations

- Revision and adaptation. Provided by: Lumen Learning and Natalia Kuznetsova. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classical_period_(music). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classical_period_(music). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike