The German Opera Tradition

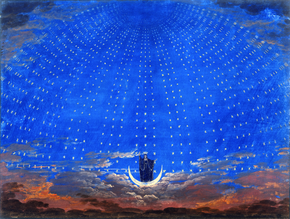

The Queen of the Night in an 1815 production of Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte

The first German opera was Dafne, composed by Heinrich Schütz in 1627, but the music score has not survived. Italian opera held a great sway over German-speaking countries until the late eighteenth century. Nevertheless, native forms would develop in spite of this influence. In 1644 Sigmund Staden produced the first Singspiel, Seelewig, a popular form of German-language opera characterized by spoken dialogue that alternated with ensembles, songs, ballads, and arias that were often strophic, or folklike. Singspiel plots are generally comic or romantic in nature, and frequently include elements of magic, fantastical creatures, and comically exaggerated characterizations of good and evil. Singspiele were considered middle-to-lower class entertainment—as opposed to the predominantly aristocratic genres of opera, ballet, and stage play—and were usually performed by traveling troupes, rather than by established companies within metropolitan centers. Mozart wrote several Singspiele: Zaide (1780), Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio) (1782), Der Schauspieldirektor (The Impresario) (1786), and finally the sophisticated Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) (1791).

Listen: Mozart Singspiele

You can listen to examples of Mozart’s operas below:

In the late seventeenth century and early eighteenth century, the Theater am Gänsemarkt in Hamburg presented German operas by Keiser, Telemann, and Handel. Yet most of the major German composers of the time, including Handel himself, as well as Graun, Hasse, and later Gluck, chose to write most of their operas in foreign languages, especially Italian. In contrast to Italian opera, which was generally composed for the aristocratic class, German opera was generally composed for the masses and tended to feature simple folk-like melodies. It was not until the arrival of Mozart that German opera was able to match its Italian counterpart in musical sophistication.

Richard Wagner

Brünnhilde throws herself onto Siegfried’s funeral pyre in Wagner’s Götterdämmerung

Opera would never be the same after Wagner and for many composers his legacy proved a heavy burden. On the other hand, Richard Strauss accepted Wagnerian ideas but took them in wholly new directions. He first won fame with the scandalous Salome and the dark tragedy Elektra, in which tonality was pushed to the limits. Then Strauss changed tack in his greatest success, Der Rosenkavalier, where Mozart and Viennese waltzes became as important an influence as Wagner. Strauss continued to produce a highly varied body of operatic works, often with libretti by the poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Other composers who made individual contributions to German opera in the early twentieth century include Alexander von Zemlinsky, Erich Korngold, Franz Schreker, Paul Hindemith, Kurt Weill and the Italian-born Ferruccio Busoni. The operatic innovations of Arnold Schoenberg and his successors are discussed in the section on modernism.

During the late nineteenth century, the Austrian composer Johann Strauss II, an admirer of the French-language operettas composed by Jacques Offenbach, composed several German-language operettas, the most famous of which was Die Fledermaus, which is still regularly performed today. Nevertheless, rather than copying the style of Offenbach, the operettas of Strauss II had distinctly Viennese flavor to them, which have cemented the Strauss II’s place as one of the most renowned operetta composers of all time.

Candela Citations

- Revision and adapation. Provided by: Lumen Learning and Natalia Kuznetsova. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Opera. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opera. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mozart - Abduction from the Seraglio. Authored by: Charles Fischer. Located at: https://youtu.be/Tw84smtNE1Q. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Mozart- Magic Flute. Queen of the Night Aria. Provided by: operascenes's channel. Located at: https://youtu.be/hqBwe9BCj4A. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Queen of the Night. Authored by: Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Karl_Friedrich_Schinkel_Die_Sternenhalle_der_K%C3%B6nigin_der_Nacht_B%C3%BChnenbild_Zauberfl%C3%B6te_Mozart.tif. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Richard Wagner. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RichardWagner.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Siegfried and the Twilight of the Gods. Authored by: Arthur Rackham. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Siegfried_and_the_Twilight_of_the_Gods_p_180.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright