The Cromford Mill (opened in 1771) today: Richard Arkwright is the person credited with inventing the prototype of the modern factory. After he patented his water frame in 1769, he established Cromford Mill, in Derbyshire, England, significantly expanding the village of Cromford to accommodate the migrant workers new to the area. It laid the foundation of Arkwright’s fortune and was quickly copied by mills in Lancashire, Germany and the United States.

Characteristics of Factory System

The factory system, considered a capitalist form of production, differs dramatically from the earlier systems of production. First, the labor generally does not own a significant share of the enterprise. The capitalist owners provide all machinery, buildings, management and administration, and raw or semi-finished materials, and are responsible for the sale of all production as well as any resulting losses. The cost and complexity of machinery, especially that powered by water or steam, was more than cottage industry workers could afford or had the skills to maintain. Second, production relies on unskilled labor. Before the factory system, skilled craftsmen would usually custom-made an entire article. In contrast, factories practiced division of labor, in which most workers were either lowskilled laborers who tended or operated machinery, or unskilled laborers who moved materials and semi-finished and finished goods. Third, factories produced products on a much larger scale than in either the putting-out or crafts systems.

The factory system also made the location of production much more flexible. Before the widespread use of steam engines and railroads, most factories were located at water power sites and near water transportation. When railroads became widespread, factories could be located away from water power sites but nearer railroads. Workers and machines were brought together in a central factory complex. Although the earliest factories were usually all under one roof, different operations were sometimes on different floors. Further, machinery made it possible to produce precisely uniform components.

Workers were paid either daily wages or for piece work, either in the form of money or some combination of money, housing, meals, and goods from a company store (the truck system). Piece work presented accounting difficulties, especially as volumes increased and workers did a narrower scope of work on each piece. Piece work went out of favor with the advent of the production line, which was designed on standard times for each operation in the sequence and workers had to keep up with the work flow.

Factory System and Society

The factory system was a new way of organizing labor made necessary by the development of machines, which were too large to house in a worker’s cottage. Working hours were as long as they had been for the farmer: from dawn to dusk, six days per week. Factories also essentially reduced skilled and unskilled workers to replaceable commodities. At the farm or in the cottage industry, each family member and worker was indispensable to a given operation and workers had to posses knowledge and often advanced skills that resulted from years of learning through practice. Conversely, under the factory system, workers were easily replaceable as skills required to operate machines could be acquired very quickly. Factory workers typically lived within walking distance to work until the introduction of bicycles and electric street railways in the 1890s. Thus, the factory system was partly responsible for the rise of urban living, as large numbers of workers migrated into the towns in search of employment in the factories. Many mills had to provide dormitories for workers, especially for girls and women.

Much manufacturing in the 18th century was carried out in homes under the domestic or putting-out system, especially the weaving of cloth and spinning of thread and yarn, often with just a single loom or spinning wheel. As these devices were mechanized, machine-made goods were able to underprice the cottagers, leaving them unable to earn enough to make their efforts worthwhile.

The transition to industrialization was not without difficulty. For example, a group of English textile workers known as Luddites protested against industrialization and sometimes sabotaged factories. They continued an already established tradition of workers opposing labor-saving machinery. Numerous inventors in the textile industry suffered harassment when developing their machines or devices. Despite the common stereotype of Luddites as opponent of progress, the group was in fact protesting the use of machinery in a “fraudulent and deceitful manner” to get around standard labor practices. They feared that the years workers had spent learning a craft would go to waste and unskilled machine operators would rob them of their livelihoods. However, in many industries the transition to factory production was not so divisive.

Frame-breakers, or Luddites, smashing a loom

Machine-breaking was criminalized by the Parliament of the United Kingdom as early as 1721. Parliament subsequently made “machine breaking” (i.e. industrial sabotage) a capital crime with the Frame Breaking Act of 1812 and the Malicious Damage Act of 1861. Lord Byron opposed this legislation, becoming one of the few prominent defenders of the Luddites.

Debate arose concerning the morality of the factory system, as workers complained about unfair working conditions. One of the problems concerned women’s labor. Women were always paid less than men and in many cases, as little as a quarter of what men made. Child labor was also a major part of the system. However, in the early 19th century, education was not compulsory and in working families, children’s wages were seen as a necessary contribution to the family budget. Automation in the late 19th century is credited with ending child labor and according to many historians, it was more effective than gradually changing child labor laws. Years of schooling began to increase sharply from the end of the 19th century, when elementary state-provided education for all became a viable concept (with the Prussian and Austrian empires as pioneers of obligatory education laws). Some industrialists themselves tried to improve factory and living conditions for their workers. One of the earliest such reformers was Robert Owen, known for his pioneering efforts in improving conditions for workers at the New Lanark mills and often regarded as one of the key thinkers of the early socialist movement.

One of the best-known accounts of factory worker’s living conditions during the Industrial Revolution is Friedrich Engels’ The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844. In it, Engels described backstreet sections of Manchester and other mill towns where people lived in crude shanties and shacks, some not completely enclosed, some with dirt floors. These shanty towns had narrow walkways between irregularly shaped lots and dwellings. There were no sanitary facilities. Population density was extremely high. Eight to ten unrelated mill workers often shared a room with no furniture and slept on a pile of straw or sawdust. Disease spread through a contaminated water supply. By the late 1880s, Engels noted that the extreme poverty and lack of sanitation he wrote about in 1844 had largely disappeared. Since then, the historical debate on the question of living conditions of factory workers has been very controversial. While some have pointed out that living conditions of the poor workers were tragic everywhere and industrialization, in fact, slowly improved the living standards of a steadily increasing number of workers, others have concluded that living standards for the majority of the population did not grow meaningfully until the late 19th and 20th centuries and that in many ways workers’ living standards declined under early capitalism.

Urbanization

Industrialization and emergence of the factory system triggered rural-to-urban migration and thus led to a rapid growth of cities, where during the Industrial Revolution workers faced the challenge of dire conditions and developed new ways of living.

Learning Objectives

Connect the development of factories to urbanization

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Industrialization led to the creation of the factory, and the factory system contributed to the growth of urban areas as large numbers of workers migrated into the cities in search of work in the factories. In England and Wales, the proportion of the population living in cities jumped from 17% in 1801 to 72% in 1891.

- In 1844, Friedrich Engels published The Condition of the Working Class in England, arguably the most important record of how workers lived during the early era of industrialization in British cities. He described backstreet sections of Manchester and other mill towns where people lived in crude shanties and overcrowded shacks, constantly exposed to contagious diseases. These conditions improved over the course of the 19th century.

- Before the Industrial Revolution, advances in agriculture or technology led to an increase in population, which again strained food and other resources, limiting increases in per capita income. This condition is called the Malthusian trap and according to some economists, it was overcome by the Industrial Revolution. Transportation advancements lowered transaction and food costs, improved distribution, and made more varied foods available in cities.

- The historical debate on the question of living conditions of factory workers has been very controversial. While some have pointed out that industrialization slowly improved the living standards of workers, others have concluded that living standards for the majority of the population did not grow meaningfully until much later.

- Not everyone lived in poor conditions and struggled with the challenges of rapid industrialization. The Industrial Revolution also created a middle class of industrialists and professionals who lived in much better conditions. In fact, one of the earlier definitions of the middle class equated the middle class to the original meaning of capitalist: someone with so much capital that they could rival nobles.

- During the Industrial Revolution, the family structure changed. Marriage shifted to a more sociable union between wife and husband in the laboring class. Women and men tended to marry someone from the same job, geographical location, or social group. Factories and mills also undermined the old patriarchal authority to a certain extent. Women working in factories faced many new challenges, including limited child-raising opportunities.

Key Terms

- Cottonopolis: A metropolis centered on cotton trading servicing the cotton mills in its hinterland. It was originally applied to Manchester, England, because of its status as the international center of the cotton and textile trade during the Industrial Revolution.

- Malthusian trap: The putative unsustainability of improvements in a society’s standard of living because of population growth. It is named for Thomas Robert Malthus, who suggested that while technological advances could increase a society’s supply of resources such as food and thereby improve the standard of living, the resource abundance would encourage population growth, which would eventually bring the per capita supply of resources back to its original level. Some economists contend that since the Industrial Revolution, mankind has broken out of the trap. Others argue that the continuation of extreme poverty indicates that the Malthusian trap continues to operate.

- Agricultural Revolution: The unprecedented increase in agricultural production in Britain due to increases in labor and land productivity between the mid-17th and late 19th centuries. Agricultural output grew faster than the population over the century to 1770, and thereafter productivity remained among the highest in the world. This increase in the food supply contributed to the rapid growth of population in England and Wales.

Factories and Urbanization

Industrialization led to the creation of the factory and the factory system contributed to the growth of urban areas as large numbers of workers migrated into the cities in search of work in the factories. Nowhere was this better illustrated than in Manchester, the world’s first industrial city, nicknamed Cottonopolis because of its mills and associated industries that made it the global center of the textile industry. Manchester experienced a six-times increase in its population between 1771 and 1831. It had a population of 10,000 in 1717, but by 1911 it had burgeoned to 2.3 million. Bradford grew by 50% every ten years between 1811 and 1851 and by 1851 only 50% of the population of Bradford was actually born there. In England and Wales, the proportion of the population living in cities jumped from 17% in 1801 to 72% in 1891.

Manchester known as Cottonopolis, pictured in 1840, showing the mass of factory chimneys, Engraving by Edward Goodall (1795-1870), original title Manchester, from Kersal Moor after a painting of W. Wylde.

Although initially inefficient, the arrival of steam power signified the beginning of the mechanization that would enhance the burgeoning textile industries in Manchester into the world’s first center of mass production. As textile manufacture switched from the home to factories, Manchester and towns in south and east Lancashire became the largest and most productive cotton spinning center in the world in 1871, with 32% of global cotton production.

Standards of Living

Friedrich Engels’ The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 is arguably the most important record of how workers lived during the early era of industrialization in British cities. Engels, who remains one of the most important philosophers of the 19th century but also came from a family of wealthy industrialists, described backstreet sections of Manchester and other mill towns where people lived in crude shanties and shacks, some not completely enclosed, some with dirt floors. These towns had narrow walkways between irregularly shaped lots and dwellings. There were no sanitary facilities. Population density was extremely high. Eight to ten unrelated mill workers often shared a room with no furniture and slept on a pile of straw or sawdust. Toilet facilities were shared if they existed. Disease spread through a contaminated water supply. New urbanites—especially small children—died due to diseases spreading because of the cramped living conditions. Tuberculosis, lung diseases from the mines, cholera from polluted water, and typhoid were all common.

The original title page of The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1944, published in German in Leipzig in 1845.

Engels’ interpretation proved to be extremely influential with British historians of the Industrial Revolution. He focused on both the workers’ wages and their living conditions. He argued that the industrial workers had lower incomes than their pre-industrial peers and lived in more unhealthy environments. This proved to be a wide-ranging critique of industrialization and one that was echoed by many of the Marxist historians who studied the industrial revolution in the 20th century.

Conditions improved over the course of the 19th century due to new public health acts regulating things like sewage, hygiene, and home construction. In the introduction of his 1892 edition, Engels notes that most of the conditions he wrote about in 1844 had been greatly improved.

Chronic hunger and malnutrition were the norm for the majority of the population of the world, including Britain and France, until the late 19th century. Until about 1750, in part due to malnutrition, life expectancy in France was about 35 years, and only slightly higher in Britain. In Britain and the Netherlands, food supply had been increasing and prices falling before the Industrial Revolution due to better agricultural practices (Agricultural Revolution).

However, population grew as well. Before the Industrial Revolution, advances in agriculture or technology led to an increase in population, which again strained food and other resources, limiting increases in per capita income. This condition is called the Malthusian trap and according to some economists, it was overcome by the Industrial Revolution. Transportation improvements, such as canals and improved roads, also lowered food costs. The post-1830 rapid development of railway further reduced transaction costs, which in turn lowered the costs of goods, including food. The distribution and sale of perishable goods such as meat, milk, fish, and vegetables was transformed by the emergence of the railways, giving rise not only to cheaper produce in the shops but also to far greater variety in people’s diets.

The question of how living conditions changed in the newly industrialized urban environment has been very controversial. A series of 1950s essays by Henry Phelps Brown and Sheila V. Hopkins set the academic consensus that the bulk of the population at the bottom of the social ladder suffered severe reductions in their living standards. Conversely, economist Robert E. Lucas, Jr., argues that the real impact of the Industrial Revolution was that the standards of living of the poorest segments of the society gradually, if slowly, improved. Others, however, have noted that while growth of the economy’s overall productive powers was unprecedented during the Industrial Revolution, living standards for the majority of the population did not grow meaningfully until the late 19th and 20th centuries and that in many ways workers’ living standards declined under early capitalism. For instance, studies have shown that real wages in Britain increased only 15% between the 1780s and 1850s and that life expectancy in Britain did not begin to dramatically increase until the 1870s.

Not everyone lived in poor conditions and struggled with the challenges of rapid industrialization. The Industrial Revolution also created a middle class of industrialists and professionals who lived in much better conditions. In fact, one of the earlier definitions of the middle class equated it to the original meaning of capitalist: someone with so much capital that they could rival nobles. To be a capital-owning millionaire was an important criterion of the middle class during the Industrial Revolution although the period witnessed also a growth of a class of professionals (e.g., lawyers, doctors, small business owners) who did not share the fate of the early industrial working class and enjoyed a comfortable standard of living in growing cities.

Changes in Family Structure

In the laboring class at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries, women traditionally married men of the same social status (e.g., a shoemaker’s daughter would marry a shoemaker’s son). Marriage outside this norm was not common. During the Industrial Revolution, marriage shifted from this tradition to a more sociable union between wife and husband in the laboring class. Women and men tended to marry someone from the same job, geographical location, or ocial group. Miners remained an exception to this trend and a coal miner’s daughter still tended to marry a coal miner’s son.

The rural pre-industrial work sphere was usually shaped by the father, who controlled the pace of work for his family. However, factories and mills undermined the old patriarchal authority to a certain extent. Factories put husbands, wives, and children under the same conditions and authority of the manufacturer masters. In the latter half of the Industrial Revolution, women who worked in factories or mills tended not to have children or had children that were old enough to take care of themselves, as life in the city made it impossible to take a child to work (unlike in the case of farm labor or cottage industry where women were more flexible to combine domestic and work spheres) and deprived women of a traditional network of support established in rural communities.

Labor Conditions

During the Industrial Revolution, laborers in factories, mills, and mines worked long hours under very dangerous conditions, though historians continue to debate the extent to which those conditions worsened the fate of the worker in pre-industrial society.

Learning Objectives

Review the conditions workers labored under in the early factories

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- As a result of industrialization, ordinary working people found increased opportunities for employment in the new mills and factories, but these were often under strict working conditions with long hours of labor dominated by a pace set by machines. The nature of work changed from a craft production model to a factory-centric model.

- In the textile industry, factories set hours of work and the machinery within them shaped the pace of work. Factories brought workers together within one building and increased the division of labor, narrowing the number and scope of tasks and including children and women within a common production process. Maltreatment, industrial accidents, and ill health from overwork and contagious diseases were common in the enclosed conditions of cotton mills. Children were particularly vulnerable.

- Work discipline was forcefully instilled upon the workforce by the factory owners, and the working conditions were dangerous and even deadly. Early industrial factories and mines created numerous health risks, and injury compensation for the workers did not exist. Machinery accidents could lead to burns, arm and leg injuries, amputation of fingers and limbs, and death. However, diseases were the most common health issues that had long-term effects.

- Mining has always been especially dangerous, and at the beginning of the 19th century, methods of coal extraction exposed men, women, and children to very risky conditions. In 1841, about 216,000 people were employed in the mines. Women and children worked underground for 11-12 hours a day. The public became aware of conditions in the country’s collieries in 1838 after an accident at Huskar Colliery in Silkstone. The disaster came to the attention of Queen Victoria who ordered an inquiry.

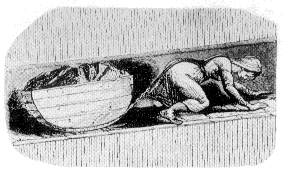

- Lord Ashley headed the royal commission of inquiry, which investigated the conditions of workers, especially children, in the coal mines in 1840. Commissioners visited collieries and mining communities gathering information, sometimes against the mine owners’ wishes. The report, illustrated by engraved illustrations and the personal accounts of mine workers, was published in 1842. The investigation led to passing one of the earlier pieces of labor legislation: the Mines and Collieries Act of 1842. It prohibited all girls and boys under ten years old from working underground in coal mines.

- Over time, more men than women would find that industrial employment and industrial wages provided a higher level of material security than agricultural employment. Consequently, women would be left behind in less-profitable agriculture. By the late 1860s, very low wages in agricultural work turned women to industrial employment on assembly lines, providing industrial laundry services, and in the textile mills. Women were never paid the same wage as a man for the same work.

Key Terms

- hurrier: A child or woman employed by a collier to transport the coal that they had mined. Women would normally get the children to help them because of the difficulty of carrying the coal. Common particularly in the early 19th century, they pulled a corf (basket or small wagon) full of coal along roadways as small as 16 inches in height. They would often work 12-hour shifts, making several runs down to the coal face and back to the surface again.

- Mines and Collieries Act: An 1842 act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which prohibited all girls and boys under ten years old from working underground in coal mines. It was a response to the working conditions of children revealed in the Children’s Employment Commission (Mines) 1842 report.

Industrial Working Practices

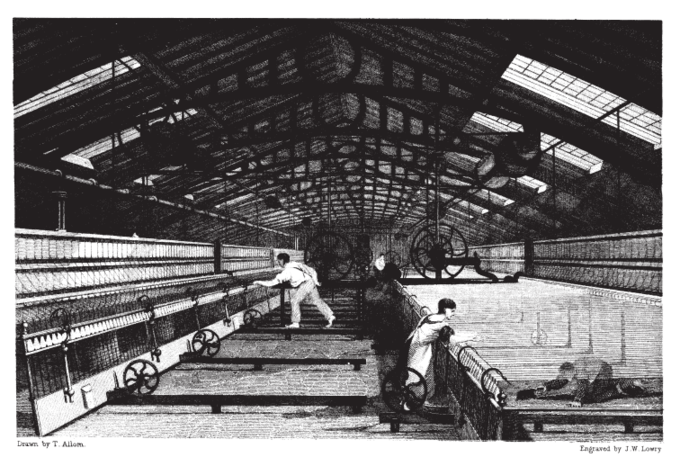

As a result of industrialization, ordinary working people found increased opportunities for employment in the new mills and factories, but these were often under strict working conditions with long hours of labor dominated by a pace set by machines. The nature of work changed from a craft production model to a factory-centric model. Between the 1760s and 1850, factories organized workers’ lives much differently than did craft production. The textile industry, central to the Industrial Revolution, serves as an illustrative example of these changes. Prior to industrialization, handloom weavers worked at their own pace, with their own tools, within their own cottages. Now, factories set hours of work and the machinery within them shaped the pace. Factories brought workers together within one building to work on machinery that they did not own. They also increased the division of labor, narrowing the number and scope of tasks and including children and women within a common production process. The early textile factories employed a large share of children and women. In 1800, there were 20,000 apprentices (usually pauper children) working in cotton mills. The apprentices were particularly vulnerable to maltreatment, industrial accidents, and ill health from overwork and widespread contagious diseases such as smallpox, typhoid, and typhus. The enclosed conditions (to reduce the frequency of thread breakage, cotton mills were usually very warm and as draft-free as possible) and close contact within mills and factories allowed contagious diseases to spread rapidly. Typhoid was spread through poor sanitation in mills and the settlements around them. In all industries, women and children made significantly lower wages than men for the same work.

A Roberts loom in a weaving shed in 1835. Illustrator T. Allom in History of the cotton manufacture in Great Britain by Sir Edward Baines.

In reference to the growing number of women in the textile industry, Friedrich Engels argued the family structure was “turned upside down” as women’s wages undercut men’s, forcing men to “sit at home” and care for children while the wife worked long hours. Historical records have shown, however, that women working the same long hours under the same dangerous conditions as men never made the same wages as men and the patriarchal model of the family was hardly undermined.

Work discipline was forcefully instilled upon the workforce by the factory owners and the working conditions were dangerous and even deadly. Early industrial factories and mines created numerous health risks, and injury compensation for the workers did not exist. Machinery accidents could lead to burns, arm and leg injuries, amputation of fingers and limbs, and death. However, diseases were the most common health issues that had long-term effects. Cotton mills, coal mines, iron-works, and brick factories all had bad air, which caused chest diseases, coughs, blood-spitting, hard breathing, pains in chest, and insomnia. Workers usually toiled extremely long hours, six days a week. However, it is important to note that historians continue to debate the question of to what extent early industrialization worsened and to what extent it improved the fate of the workers, as working practices and conditions in the pre-industrial society were similarly difficult. Child labor, dangerous working conditions, and long hours were just as prevalent before the Industrial Revolution.

Mining has always been especially dangerous and at the beginning of the 19th century, methods of coal extraction exposed men, women, and children to very risky conditions. In 1841, about 216,000 people were employed in the mines. Women and children worked underground for 11-12 hours a day. The public became aware of conditions in the country’s collieries in 1838 after an accident at Huskar Colliery in Silkstone, near Barnsley. A stream overflowed into the ventilation drift after violent thunderstorms, causing the death of 26 children, 11 girls ages 8 to 16 and 15 boys between 9 and 12 years of age. The disaster came to the attention of Queen Victoria, who ordered an inquiry. Lord Ashley headed the royal commission of inquiry, which investigated the conditions of workers, especially children, in the coal mines in 1840. Commissioners visited collieries and mining communities gathering information, sometimes against the mine owners’ wishes. The report, illustrated by engraved illustrations and the personal accounts of mine workers, was published in 1842. The middle class and elites were shocked to learn that children as young as five or six worked as trappers, opening and shutting ventilation doors down the mine before becoming hurriers, pushing and pulling coal tubs and corfs. The investigation led to

one of the earlier pieces of labor legislation: the Mines and Collieries Act of 1842. It prohibited all girls and boys under ten years old from working underground in coal mines.

Working-Class Women

Before the Mines and Collieries Act 1842, women (and children) worked underground as hurriers who carted tubs of coal up through the narrow mine shafts. In Wolverhampton, the law did not have much of an impact on women’s mining employment because they mainly worked above-ground at the coal mines, sorting coal, loading canal boats, and other surface tasks. Over time, more men than women would find industrial employment, and industrial wages provided a higher level of material security than agricultural employment. Consequently, women, who were traditionally involved in all agricultural labor, would be left behind in less-profitable agriculture. By the late 1860s, very low wages in agricultural work turned women to industrial employment.

In industrialized areas, women could find employment on assembly lines, providing industrial laundry services, and in the textile mills that sprang up during the Industrial Revolution in such cities as Manchester, Leeds, and Birmingham. Spinning and winding wool, silk, and other types of piecework were a common way of earning income by working from home, but wages were very low and hours long. Often 14 hours per day were needed to earn enough to survive. Needlework was the single highest-paid occupation for women working from home, but the work paid little and women often had to rent sewing machines that they could not afford to buy. These home manufacturing industries became known as “sweated industries” (think of today’s sweat shops). The Select Committee of the House of Commons defined sweated industries in 1890 as “work carried on for inadequate wages and for excessive hours in unsanitary conditions.” By 1906, such workers earned about a penny an hour. Women were never paid the same wage as a man for the same work, despite the fact that they were as likely as men to be married and supporting children.

Child Labor

Although child labor was widespread prior to industrialization, the exploitation of child workforce intensified during the Industrial Revolution.

Learning Objectives

Indicate the circumstances leading to the use of industrial child labor

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- With the onset of the Industrial Revolution in Britain in the late 18th century, there was a rapid increase in the industrial exploitation of labor, including child labor. Child labor became the labor of choice for manufacturing in the early phases of the Industrial Revolution because children were paid much less while being as productive as adults and were more vulnerable. Their smaller size was also perceived as an advantage.

- Children as young as four were employed in production factories and mines working long hours in dangerous, often fatal conditions. In coal mines, children would crawl through tunnels too narrow and low for adults. They also worked as errand boys, crossing sweepers, shoe blacks, or selling matches, flowers, and other cheap goods.

- Many children were forced to work in very poor conditions for much lower pay than their elders, usually 10–20% of an adult male’s wage. Beatings and long hours were common, with some child coal miners and hurriers working from 4 a.m. until 5 p.m. Many children developed lung cancer and other diseases. Death before age 25 was common for child workers.

- Workhouses would sell orphans and abandoned children as “pauper apprentices,” working without wages for board and lodging. In 1800, there were 20,000 apprentices working in cotton mills. The apprentices were particularly vulnerable to maltreatment, industrial accidents, and ill health from overwork, and contagious diseases such as smallpox, typhoid, and typhus.

- The first legislation in response to the abuses experienced by child laborers did not even attempt to ban child labor, but merely improve working conditions for some child workers. The Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802 was designed to improve conditions for apprentices working in cotton mills. It was not until 1819 that an Act to limit the hours of work and set a minimum age for free children working in cotton mills was piloted through Parliament.

- A series of acts limiting provisions under which children could be employed followed the two largely ineffective Acts of 1802 and 1819, including the Mines and Collieries Act 1842, the Factories Act 1844, and the Factories Act 1847. The last two major factory acts of the Industrial Revolution were introduced in 1850 and 1856. Factories could no longer dictate work hours for women and children.

Key Terms

- Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802: An 1802 Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, sometimes known as the Factory Act 1802, was designed to improve conditions for apprentices working in cotton mills. The Act was introduced by Sir Robert Peel, who became concerned with the issue after an 1784 outbreak of a “malignant fever” at one of his cotton mills, which he later blamed on “gross mismanagement” by his subordinates.

- hurrier: A child or woman employed by a collier to transport the coal that they had mined. Women would normally get the children to help them because of the difficulty of carrying the coal. Common particularly in the early 19th century, they pulled a corf (basket or small wagon) full of coal along roadways as small as 16 inches in height. They would often work 12-hour shifts, making several runs down to the coal face and back to the surface again.

- Second Industrial Revolution: A phase of rapid industrialization in the final third of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. Although a number of its characteristic events can be traced to earlier innovations in manufacturing, such as the establishment of a machine tool industry, the development of methods for manufacturing interchangeable parts, and the invention of the Bessemer Process, it is generally dated between 1870 and 1914.

- Mines and Collieries Act 1842: An 1842 act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that prohibited banned) all girls and boys younger than age 10 from working underground in coal mines. It was a response to the working conditions of children revealed in the Children’s Employment Commission (Mines) 1842 report.

- Cotton Mills and Factories Act of 1819: An 1819 Act of Parliament in the United Kingdom that stated that no children under 9 were to be employed and that children aged 9–16 years were limited to 12 hours’ work per day. It applied to the cotton industry only, but covered all children, whether apprentices or not. It was seen through Parliament by Sir Robert Peel but had its origins in a draft prepared by Robert Owen in 1815. The Act that emerged in 1819 was watered down from Owen’s draft.

The Industrial Child Workforce

With the onset of the Industrial Revolution in Britain in the late 18th century, there was a rapid increase in the industrial exploitation of labor, including child labor. The population grew and although chances of surviving childhood did not improve, infant mortality rates decreased markedly. Education opportunities for working-class families were limited and children were expected to contribute to family budgets just like adult family members. Child labor became the labor of choice for manufacturing in the early phases of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries. In England and Scotland in 1788, two-thirds of the workers in 143 water-powered cotton mills were described as children. Employers paid a child less than an adult even though their productivity was comparable. There was no need for strength to operate an industrial machine and since the industrial system was completely new, there were no experienced adult laborers. Factory and mine owners preferred child labor also because they perceived the child workers’ smaller size as an advantage. In textile factories, children were desired because of their supposed “nimble fingers,” while low and narrow mine galleries made children particularly effective mine workers.

The Victorian era (overlapping with approximately the last decade of the Industrial Revolution and largely with what is known as the Second Industrial Revolution) in particular became notorious for the conditions, under which children were employed. Children as young as four worked long hours in production factories and mines in dangerous, often fatal conditions. In coal mines, children would crawl through tunnels too narrow and low for adults. They also worked as errand boys, crossing sweepers, shoe blacks, or selling matches, flowers, and other cheap goods. Some children undertook work as apprentices to trades considered respectable, such as building or as domestic servants (there were over 120,000 domestic servants in London in the mid-18th century). Working hours were long: builders worked 64 hours a week in summer and 52 in winter, while domestic servants worked 80-hour weeks.

A young drawer pulling a coal tub along a mine gallery, source unknown.

Agile boys were employed by the chimney sweeps. Small children were employed to scramble under machinery to retrieve cotton bobbins and in coal mines, crawling through tunnels too narrow and low for adults. Many young people worked as prostitutes (the majority of prostitutes in London were between 15 and 22 years of age).

Child labor existed long before the Industrial Revolution, but with the increase in population and education, it became more visible. Furthermore, unlike in agriculture and cottage industries where children often contributed to the family operation, children in the industrial employment were independent workers with no protective mechanisms in place. Many children were forced to work in very poor conditions for much lower pay than their elders, usually 10–20% of an adult male’s wage. Children as young as four were employed. Beatings and long hours were common, with some child coal miners and hurriers working from 4 a.m. until 5 p.m. Conditions were dangerous, with some children killed when they dozed off and fell into the path of the carts, while others died from gas explosions. Many children developed lung cancer and other diseases. Death before the age of 25 was common for child workers.

Those child laborers who ran away would be whipped and returned to their masters, with some masters shackling them to prevent escape. Children employed as mule scavengers by cotton mills would crawl under machinery to pick up cotton, working 14 hours a day, six days a week. Some lost hands or limbs, others were crushed under the machines, and some were decapitated. Young girls worked at match factories, where phosphorus fumes would cause many to develop phossy jaw, an extremely painful condition that disfigured the patient and eventually caused brain damage, with dying bone tissue accompanied by a foul-smelling discharge. Children employed at glassworks were regularly burned and blinded, and those working at potteries were vulnerable to poisonous clay dust.

Workhouses would sell orphans and abandoned children as “pauper apprentices,” working without wages for board and lodging. In 1800, there were 20,000 apprentices working in cotton mills. The apprentices were particularly vulnerable to maltreatment, industrial accidents, and ill health from overwork and contagious diseases such as smallpox, typhoid, and typhus. The enclosed conditions (to reduce the frequency of thread breakage, cotton mills were usually very warm and as draft-free as possible) and close contact within mills and factories allowed contagious diseases such as typhus and smallpox to spread rapidly, especially because sanitation in mills and the settlements around them was often poor. Around 1780, a water-powered cotton mill was built for Robert Peel on the River Irwell near Radcliffe. The mill employed children bought from workhouses in Birmingham and London. They were unpaid and bound apprentices until they were 21, which in practice made them enslaved labor. They boarded on an upper floor of the building and were locked inside. Shifts were typically 10–10.5 hours in length (i.e. 12 hours after allowing for meal breaks) and the apprentices “hot bunked,” meaning a child who had just finished his shift would sleep in a bed just vacated by a child now starting his shift.

Children at work in a cotton mill (Mule spinning, England 1835). Illustrations from Edward Baines, The History of the Cotton Manufacture in Great Britain, H. Fisher, R. Fisher, and P. Jackson, 1835.

Children as young as 4 were put to work. In coal mines, children began work at the age of 5 and generally died before the age of 25. Many children (and adults) worked 16-hour days.

Early Attempts to Ban Child Labor

The first legislation in response to the abuses experienced by child laborers did not even attempt to ban child labor but merely to improve working conditions for some child workers. The Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802, sometimes known as the Factory Act 1802, was designed to improve conditions for apprentices working in cotton mills. The Act was introduced by Sir Robert Peel, who became concerned after a 1784 outbreak of a “malignant fever” at one of his cotton mills, which he later blamed on “gross mismanagement” by his subordinates. The Act required that cotton mills and factories be properly ventilated and basic requirements on cleanliness be met. Apprentices in these premises were to be given a basic education and attend a religious service at least once a month. They were to be provided with clothing and their working hours were limited to no more than twelve hours a day (excluding meal breaks). They were not to work at night.

Despite its modest provisions, the 1802 Act was not effectively enforced and did not address the working conditions of free children, who were not apprentices and who rapidly came to heavily outnumber the apprentices in mills. Regulating the way masters treated their apprentices was a recognized responsibility of Parliament and hence the Act itself was non-contentious, but coming between employer and employee to specify on what terms a person might sell their labor (or that of their children) was highly contentious. Hence it was not until 1819 that an Act to limit the hours of work (and set a minimum age) for free children working in cotton mills was piloted through Parliament by Peel and his son Robert (the future Prime Minister). Strictly speaking, Peel’s Cotton Mills and Factories Act of 1819 paved the way for subsequent Factory Acts and set up effective means of industry regulation.

These 1802 and 1819 Acts were largely ineffective and after radical agitation by child labor opponents, a Royal Commission recommended in 1833 that children aged 11–18 should work a maximum of 12 hours per day, children aged 9–11 a maximum of eight hours, and children under the age of nine were no longer permitted to work. This act, however, only applied to the textile industry, and further agitation led to another act in 1847 limiting both adults and children to 10-hour working days.

In 1841, about 216,000 people were employed in the mines. Women and children worked underground for 11 or 12 hours a day for smaller wages than men. The public became aware of conditions in the country’s collieries in 1838 after an accident at Huskar Colliery in Silkstone, near Barnsley. A stream overflowed into the ventilation drift after violent thunderstorms causing the death of 26 children, 11 girls ages 8 to 16 and 15 boys between 9 and 12 years of age. The disaster came to the attention of Queen Victoria, who ordered an inquiry. Lord Ashley headed the royal commission of inquiry that investigated the conditions of workers, especially children, in the coal mines in 1840. Commissioners visited collieries and mining communities gathering information, sometimes against the mine owners’ wishes. The report, illustrated by engraved illustrations and the personal accounts of mine workers, was published in 1842. Victorian society was shocked to discover that children as young as five or six worked as trappers, opening and shutting ventilation doors down the mine before becoming hurriers, pushing and pulling coal tubs and corfs. As a result, the Mines and Collieries Act 1842, commonly known as the Mines Act of 1842, was passed. It prohibited all girls and boys under ten years old from working underground in coal mines.

The Factories Act 1844 banned women and young adults from working more than 12-hour days and children from the ages 9 to 13 from working 9-hour days. The Factories Act 1847, also known as the Ten Hours Act, made it illegal for women and young people (13-18) to work more than 10 hours and maximum 63 hours a week in textile mills. The last two major factory acts of the Industrial Revolution were introduced in 1850 and 1856. Factories could no longer dictate work hours for women and children, who were to work from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. in the summer and 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. in the winter. These acts deprived the manufacturers of a significant amount of power and authority.

Organized Labor & Political Reactions

The concentration of workers in factories, mines, and mills facilitated the development of trade unions during the Industrial Revolution. After the initial decades of political hostility towards organized labor, skilled male workers emerged as the early beneficiaries of the labor movement.

Learning Objectives

Describe the grievances that gave rise to organized labor

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The rapid expansion of industrial society during the Industrial Revolution drew women, children, rural workers, and immigrants into the industrial work force in large numbers and in new roles. This pool of unskilled and semi-skilled labor spontaneously organized in fits and starts throughout the early phases of industrialization and would later be an important arena for the development of trade unions.

- As collective bargaining and early worker unions grew with the onset of the Industrial Revolution, the government began to clamp down on what it saw as the danger of popular unrest at the time of the Napoleonic Wars. In 1799, the Combination Act was passed, which banned trade unions and collective bargaining by British workers. Although the unions were subject to often severe repression until 1824, they were already widespread in some cities and workplace militancy manifested itself in many different ways.

- By the 1810s, the first labor organizations to bring together workers of divergent occupations were formed. Possibly the first such union was the General Union of Trades, also known as the Philanthropic Society, founded in 1818 in Manchester. Under the pressure of both workers and the middle and upper-class activists sympathetic of the workers’ repeal, the law banning unions was repealed in 1824. However, the Combinations of Workmen Act 1825 severely restricted their activity.

- The first attempts at a national general union were made in the 1820s and 1830s. The National Association for the Protection of Labor was established in 1830 by John Doherty. The Association quickly enrolled approximately 150 unions, consisting mostly of textile workers but also mechanics, blacksmiths, and various others. In 1834, Welsh socialist Robert Owen established the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union. The organization attracted a range of socialists from Owenites to revolutionaries and played a part in the protests after the Tolpuddle Martyrs ‘ case.

- In the later 1830s and 1840s, trade unionism was overshadowed by political activity. Of particular importance was Chartism, a working-class movement for political reform in Britain that existed from 1838 to 1858. The strategy employed the large-scale support to put pressure on politicians to concede manhood suffrage. Chartism thus relied on constitutional methods to secure its aims.

- More permanent trade unions followed from the 1850s. They were usually better resourced but often less radical. In some trades, unions were led and controlled by skilled workers, which essentially excluded the interests of the unskilled labor. Women were largely excluded from trade union formation, membership, and hierarchies until the late 20th century. Unions were eventually legalized in 1871 with the adoption of the Trade Union Act 1871.

Key Terms

- Combinations of Workmen Act 1825: An 1825 Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom, which prohibited trade unions from attempting to collectively bargain for better terms and conditions at work and suppressed the right to strike.

- Combination Act: A 1799 Act of Parliament that prohibited trade unions and collective bargaining by British workers.

- Luddites: A group of English textile workers and self-employed weavers in the 19th century who used the destruction of machinery as a form of protest. The group was protesting the use of machinery in a “fraudulent and deceitful manner” to get around standard labor practices. They were fearful that the years they had spent learning the craft would go to waste and unskilled machine operators would rob them of their livelihood.

- Radical War: A week of strikes and unrest, also known as the Scottish Insurrection of 1820, that was a culmination of Radical demands for reform in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland which became prominent in the early years of the French Revolution, but were then repressed during the long Napoleonic Wars.

- Chartism: A working-class movement for political reform in Britain that existed from 1838 to 1857. It took its name from the People’s Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement. The strategy employed was to use the large scale of support for numerous petitions and the accompanying mass meetings to put pressure on politicians to concede manhood suffrage.

- Tolpuddle Martyrs: A group of 19th century Dorset agricultural laborers who were convicted of swearing a secret oath as members of the Friendly Society of Agricultural Laborers. At the time, friendly societies had strong elements of what are now considered to be the predominant role of trade unions. The group were subsequently sentenced to penal transportation to Australia.

Industrialization and Labor Organization

The rapid expansion of industrial society during the Industrial Revolution drew women, children, rural workers, and immigrants into the industrial work force in large numbers and in new roles. This pool of unskilled and semi-skilled labor spontaneously organized in fits and starts throughout the early phases of industrialization and would later be an important arena for the development of trade unions. Trade unions have sometimes been seen as successors to the guilds of medieval Europe, although the relationship between the two is disputed as the masters of the guilds employed workers (apprentices and journeymen) who were not allowed to organize. The concentration of labor in mills, factories, and mines facilitated the organization of workers to help advance the interests of working people. A union could demand better terms by withdrawing all labor and causing a consequent cessation of production. Employers had to decide between giving in to the union demands at a cost to themselves or suffering the cost of the lost production. Skilled workers were hard to replace and these were the first groups to successfully advance their conditions through this kind of bargaining.

Trade unions and collective bargaining were outlawed from no later than the middle of the 14th century when the Ordinance of Laborers was enacted in the Kingdom of England. As collective bargaining and early worker unions grew with the onset of the Industrial Revolution, the government began to clamp down on what it saw as the danger of popular unrest at the time of the Napoleonic Wars. In 1799, the Combination Act was passed, which banned trade unions and collective bargaining by British workers. Although the unions were subject to often severe repression until 1824, they were already widespread in some cities.

Workplace militancy manifested itself in many different ways. For example, Luddites were a group of English textile workers and self-employed weavers who in the 19th century destroyed weaving machinery as a form of protest. The group was protesting the use of machinery to get around standard labor practices, fearing that the years they had spent learning the craft would go to waste and unskilled machine operators would rob them of their livelihoods. One of the first mass work strikes emerged in 1820 in Scotland, an event known today as the Radical War. 60,000 workers went on a general strike. Their demands went far beyond labor regulations and included a general call for reforms. The strike was quickly crushed.

In 1848 Engels joined Karl Marx in the writing and publication of “The Communist Manifesto.” It was commissioned by the Communist League of England and presents the major points of the communist movement and the communist party. Despite being a brief document the Manifesto would become one of the most influential and controversial writings of the modern era. Fundamentally it was a political tract, but the Manifesto also presented a philosophical and theoretical basis for understanding industrialization and urbanization. Importantly the Manifesto maintained that all of human history had been a history of class struggle. Industrialization had magnified that class conflict. In the industrial era was dominated by two classes within society. The bourgeoisie were those people who owned property and in particular the means of production. The proletariat did not own property and worked for the bourgeoisie. The result was a relationship of exploitation and society dominated by class conflict. This exploitation could only be resolved by a proletarian “revolution”–whether this revolution could be peaceful or not was a subject of much debate–and by doing away with private ownership of the means of production.

Early Trade Unions

By the 1810s, the first labor organizations to bring together workers of divergent occupations were formed. Possibly the first such union was the General Union of Trades, also known as the Philanthropic Society, founded in 1818 in Manchester. The latter name was to hide the organization’s real purpose in a time when trade unions were still illegal.

Under the pressure of both workers and the middle and upper class activists sympathetic of the workers’ repeal, the law banning unions was repealed in 1824. However, the Combinations of Workmen Act 1825 severely restricted their activity. It prohibited trade unions from attempting to collectively bargain for better terms and conditions at work and suppressed the right to strike. That did not stop the fledgling labor movements and unions began forming rapidly.

The first attempts at setting up a national general union were made in the 1820s and 1830s. The National Association for the Protection of Labor was established in 1830 by John Doherty, after an apparently unsuccessful attempt to create a similar national presence with the National Union of Cotton Spinners. The Association quickly enrolled approximately 150 unions, consisting mostly of textile workers, but also including mechanics, blacksmiths, and various others. Membership rose to between 10,000 and 20,000 individuals spread across the five counties of Lancashire, Cheshire, Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, and Leicestershire within a year. To establish awareness and legitimacy, the union started the weekly Voice of the People publication, with the declared intention “to unite the productive classes of the community in one common bond of union.”

Meeting of the trade unionists in Copenhagen Fields in 1834, for the purpose of carrying a petition to the King for a remission of the sentence passed on the Dorchester (Dorset county) laborers

In England, the members of the Friendly Society of Agricultural laborers became popular heroes and 800,000 signatures were collected for their release. Their supporters organized a political march, one of the first successful marches in the UK, and all were pardoned on condition of good conduct in 1836.

In 1834, Welsh socialist Robert Owen established the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union. The organization attracted a range of socialists from Owenites to revolutionaries and played a part in the protests after the Tolpuddle Martyrs’ case. In 1833, six men from Tolpuddle in Dorset founded the Friendly Society of Agricultural Laborers to protest against the gradual lowering of agricultural wages. The Tolpuddle laborers refused to work for less than 10 shillings a week, although by this time wages had been reduced to seven shillings and would be further reduced to six. In 1834, James Frampton, a local landowner and magistrate, wrote to Home Secretary Lord Melbourne to complain about the union. As a result of obscure law that prohibited the swearing of secret oaths, six men were arrested, tried, found guilty, and transported to Australia. Owen’s union collapsed shortly afterwards.

Chartism

In the later 1830s and 1840s, trade unionism was overshadowed by political activity. Of particular importance was Chartism, a working-class movement for political reform in Britain that existed from 1838 to 1858. It took its name from the People’s Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, with particular strongholds of support in Northern England, the East Midlands, the Staffordshire Potteries, the Black Country, and the South Wales Valleys. Support for the movement was at its highest in 1839, 1842, and 1848, when petitions signed by millions of working people were presented to Parliament. The strategy used the scale of support demonstrated these petitions and the accompanying mass meetings to put pressure on politicians to concede manhood suffrage. Chartism thus relied on constitutional methods to secure its aims, although there were some who became involved in radical activities, notably in south Wales and Yorkshire. The government did not yield to any of the demands and suffrage had to wait another two decades. Chartism was popular among some trade unions, especially London’s tailors, shoemakers, carpenters, and masons. One reason was the fear of the influx of unskilled labor, especially in tailoring and shoe making. In Manchester and Glasgow, engineers were deeply involved in Chartist activities. Many trade unions were active in the general strike of 1842, which spread to 15 counties in England and Wales and eight in Scotland. Chartism taught techniques and political skills that inspired trade union leadership.

Photograph of the Great Chartist Meeting on Kennington Common, London in 1848, by William Edward Kilburn.

Chartists saw themselves fighting against political corruption and for democracy in an industrial society, but attracted support beyond the radical political groups for economic reasons, such as opposing wage cuts and unemployment.

Full Legalization

After the Chartist movement of 1848 fragmented, efforts were made to form a labor coalition. The Miners’ and Seamen’s United Association in the North-East operated 1851–1854 before it too collapsed because of outside hostility and internal disputes over goals. The leaders sought working-class solidarity as a long-term aim. More permanent trade unions followed from the 1850s. They were usually better resourced but often less radical. The London Trades Council was founded in 1860 and the Sheffield Outrages spurred the establishment of the Trades Union Congress in 1868. By this time, the existence and the demands of the trade unions were becoming accepted by liberal middle-class opinion. Further, in some trades, unions were led and controlled by skilled workers, which essentially excluded the interests of the unskilled labor. For example, in textiles and engineering, union activity from the 1850s to as late as the mid-20th century was largely in the hands of the skilled workers. They supported differentials in pay and status as opposed to the unskilled. They focused on control over machine production and were aided by competition among firms in the local labor market.

The legal status of trade unions in the United Kingdom was eventually established by a Royal Commission on Trade Unions in 1867, which agreed that the establishment of the organizations was to the advantage of both employers and employees. Unions were legalized with the adoption of the Trade Union Act 1871.

Exclusion of Women

Women were largely excluded from trade union formation, membership, and hierarchies until the late 20th century. When women did succeed in challenging male hegemony and made inroads into the representation of labor and combination, it was originally not working-class women but middle-class reformers such as the Women’s Protective and Provident League (WPPL), which sought to amiably discuss conditions with employers in the 1870s. It became the Women’s Trade Union League, members of which were largely upper-middle-class men and women interested in social reform, who wanted to educate women in trade unionism and fund the establishment of trade unions. Militant socialists broke away from the WPPL and formed the Women’s Trade Union Association, but they had little impact. However, there were a few cases in the 19th century where women trade union members took initiative. For example, women played a central role in the 1875 West Yorkshire weavers’ strike.

Candela Citations

- The Communist Manifesto. Provided by: Study.com. Located at: https://study.com/academy/lesson/the-communist-manifesto-summary-analysis-quiz.html. License: All Rights Reserved

- Factory system. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Factory_system. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Factory. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Factory. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Etruria Works. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Etruria_Works. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Josiah Wedgwood. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josiah_Wedgwood. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Soho Manufactory. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soho_Manufactory. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cromford Mill. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cromford_Mill. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Luddite. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luddite. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Truck system. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Truck_system. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Putting-out system. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Putting-out_system. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- FrameBreaking-1812.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FrameBreaking-1812.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cromford_1771_mill.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cromford_1771_mill.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Middle class. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_class. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Industrial Revolution. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_Revolution. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Malthusian trap. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malthusian_trap. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- History of rail transport. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_rail_transport. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cottonopolis. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cottonopolis. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- British Agricultural Revolution. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Agricultural_Revolution. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Factory system. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Factory_system. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Life in Great Britain during the Industrial Revolution. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Life_in_Great_Britain_during_the_Industrial_Revolution. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Urbanization. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urbanization. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Condition of the Working Class in England. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Condition_of_the_Working_Class_in_England. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- FrameBreaking-1812.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FrameBreaking-1812.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cromford_1771_mill.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cromford_1771_mill.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Die_Lage_der_arbeitenden_Klasse_in_England.png. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Die_Lage_der_arbeitenden_Klasse_in_England.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cottonopolis1.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cottonopolis1.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Industrial Revolution. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_Revolution. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mines and Collieries Act 1842. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mines_and_Collieries_Act_1842. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Women in the Victorian era. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women_in_the_Victorian_era. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Life in Great Britain during the Industrial Revolution. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Life_in_Great_Britain_during_the_Industrial_Revolution. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Health_and_Morals_of_Apprentices_Act_1802. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Textile_manufacture_during_the_Industrial_Revolution. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- History of coal mining. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_coal_mining. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Hurrying. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hurrying. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- FrameBreaking-1812.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FrameBreaking-1812.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cromford_1771_mill.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cromford_1771_mill.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Die_Lage_der_arbeitenden_Klasse_in_England.png. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Die_Lage_der_arbeitenden_Klasse_in_England.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cottonopolis1.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cottonopolis1.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Powerloom_weaving_in_1835.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Powerloom_weaving_in_1835.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Second Industrial Revolution. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Industrial_Revolution. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mines and Collieries Act 1842. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mines_and_Collieries_Act_1842. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Child labour. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Child_labour. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Industrial Revolution. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_Revolution. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Health_and_Morals_of_Apprentices_Act_1802. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Factories Act 1847. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Factories_Act_1847. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Victorian era. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victorian_era. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Factory Acts. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Factory_Acts. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- History of coal mining. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_coal_mining. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Hurrying. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hurrying. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Phossy jaw. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phossy_jaw. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Life in Great Britain during the Industrial Revolution. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Life_in_Great_Britain_during_the_Industrial_Revolution. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- FrameBreaking-1812.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FrameBreaking-1812.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cromford_1771_mill.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cromford_1771_mill.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Die_Lage_der_arbeitenden_Klasse_in_England.png. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Die_Lage_der_arbeitenden_Klasse_in_England.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cottonopolis1.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cottonopolis1.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Powerloom_weaving_in_1835.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Powerloom_weaving_in_1835.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Baines_1835-Mule_spinning.png. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baines_1835-Mule_spinning.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Coaltub.png. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coaltub.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Luddite. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luddite. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Industrial Revolution. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_Revolution. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Radical War. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radical_War. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Trade Union Act 1871. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trade_Union_Act_1871. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Emma Paterson. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emma_Paterson. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chartism. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chartism. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- History of trade unions in the United Kingdom. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_trade_unions_in_the_United_Kingdom. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Trade union. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trade_union. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Combinations of Workmen Act 1825. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Combinations_of_Workmen_Act_1825. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tolpuddle Martyrs. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tolpuddle_Martyrs. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Combination Act 1799. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Combination_Act_1799. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- FrameBreaking-1812.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FrameBreaking-1812.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cromford_1771_mill.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cromford_1771_mill.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Die_Lage_der_arbeitenden_Klasse_in_England.png. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Die_Lage_der_arbeitenden_Klasse_in_England.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cottonopolis1.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cottonopolis1.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Powerloom_weaving_in_1835.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Powerloom_weaving_in_1835.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Baines_1835-Mule_spinning.png. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baines_1835-Mule_spinning.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Coaltub.png. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coaltub.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Meeting_of_the_trade_unionists_in_Copenhagen_Fields_April_21_1834_for_the_purpose_of_carrying_a_petition_to_the_King_for_a_remission_of_the_sentence_passed_on_the_Dorchester_labourers_1293402.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Meeting_of_the_trade_unionists_in_Copenhagen_Fields,_April_21,_1834,_for_the_purpose_of_carrying_a_petition_to_the_King_for_a_remission_of_the_sentence_passed_on_the_Dorchester_labourers_(1293402).jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 1024px-William_Edward_Kilburn_-_View_of_the_Great_Chartist_Meeting_on_Kennington_Common_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William_Edward_Kilburn_-_View_of_the_Great_Chartist_Meeting_on_Kennington_Common_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright