LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the process of binary fission in prokaryotes

Prokaryotes reproduce by binary fission. The genomic DNA must be replicated and then distributed into the daughter cells. The cytoplasmic contents must be divided to give both new cells the machinery to sustain life. In bacterial cells, the genome consists of a single, circular DNA chromosome. Mitosis is unnecessary because there is no nucleus or multiple chromosomes.

Binary Fission

Binary fission is a less complicated, quicker process than cell division found in eukaryotes. Due to this speed, populations of bacteria can grow very rapidly. The single, circular DNA chromosome of bacteria is occupied in the nucleoid within the cell. This DNA is associated with proteins to aid in packaging the molecule into a compact size.

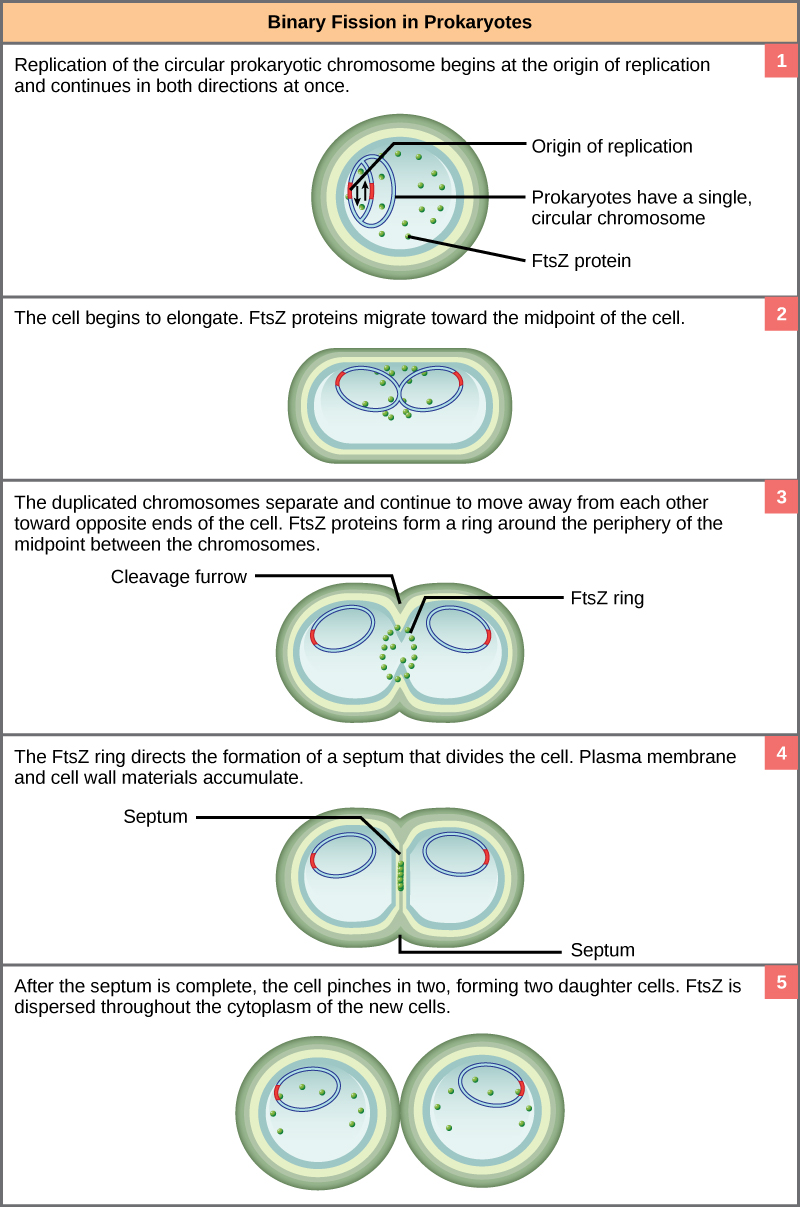

The starting point of replication, the origin, is close to the binding site of the chromosome near the plasma membrane (Figure 1). Replication of the DNA moves away from the origin on both strands of the DNA loop simultaneously. As the new double strands are formed, each origin point moves away from the cell-wall attachment toward opposite ends of the cell. The cell elongates and the growing membrane aids in chromosome transport. After the chromosomes have cleared the midpoint of the elongated cell, cytoplasmic separation begins. A septum is formed between the nucleoids from the periphery toward the center of the cell. When the new cell walls are in place, the daughter cells separate.

Figure 1. The binary fission of a bacterium is outlined in five steps. (credit: modification of work by “Mcstrother”/Wikimedia Commons)

Evolution in Action

Mitotic Spindle Apparatus

The precise timing and formation of the mitotic spindle is critical to the success of eukaryotic cell division. Prokaryotic cells, on the other hand, do not undergo mitosis and therefore have no need for a mitotic spindle. The FtsZ protein that plays such a vital role in prokaryotic cytokinesis is structurally and functionally very similar to the protein(tubulin) that makes up the mitotic spindle. The formation of a ring, composed of repeating units of a protein called FtsZ, directs the partition between the nucleoids in prokaryotes. Formation of the FtsZ ring triggers the accumulation of other proteins that are needed to complete the separation. FtsZ proteins can form filaments, rings, and other three-dimensional structures resembling the way tubulin forms microtubules, centrioles, and various cytoskeleton components.

A survey of cell-division machinery in present-day unicellular eukaryotes reveals crucial intermediary steps to the complex mitotic machinery of multicellular eukaryotes (Table 1). The mitotic spindle fibers of eukaryotes are composed of microtubules. Microtubules are polymers of the protein tubulin. The FtsZ protein, active in prokaryote cell division, is very similar to tubulin. Similarities occur in the structures formed and the energy source. Single-celled eukaryotes display possible intermediary steps between FtsZ activity during binary fission in prokaryotes and the mitotic spindle in multicellular eukaryotes, during which the nucleus breaks down and is reformed.

| Table 1. Mitotic Spindle Evolution | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure of genetic material | Division of nuclear material | Separation of daughter cells | |

| Prokaryotes | There is no nucleus. The single, circular chromosome exists in a region of cytoplasm called the nucleoid. | Occurs through binary fission. As the chromosome is replicated, the two copies move to opposite ends of the cell by an unknown mechanism. | FtsZ proteins assemble into a ring that pinches the cell in two. |

| Some protists | Linear chromosomes exist in the nucleus. | Chromosomes attach to the nuclear envelope, which remains intact. The mitotic spindle passes through the envelope and elongates the cell. No centrioles exist. | Microfilaments form a cleavage furrow that pinches the cell in two. |

| Other protists | Linear chromosomes exist in the nucleus. | A mitotic spindle forms from the centrioles and passes through the nuclear membrane, which remains intact. Chromosomes attach to the mitotic spindle. The mitotic spindle separates the chromosomes and elongates the cell. | Microfilaments form a cleavage furrow that pinches the cell in two. |

| Animal cells | Linear chromosomes exist in the nucleus. | A mitotic spindle forms from the centrioles. The nuclear envelope dissolves. Chromosomes attach to the mitotic spindle, which separates them and elongates the cell. |

Microfilaments form a cleavage furrow that pinches the cell in two. |

Candela Citations

- Prokaryotic Cell Division. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: http://cnx.org/content/col11407/latest.. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download the original material for free at http://cnx.org/content/col11407/latest.