Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What kinds of people are elected to Congress?

- How do members make news and generate publicity for themselves?

- What jobs are performed by congressional staff members?

Members of Congress are local politicians serving in a national institution. They spend their days moving between two worlds—their home districts and Washington. While many come from the ranks of the social and economic elite, to be successful they must be true to their local roots.

Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords (D-AZ) was shot outside a grocery store where she was holding a “Congress on Your Corner” event to meet personally with constituents in her district in 2011. Six people were killed, including a nine-year-old girl, in the incident, which raised issues about the safety of members of Congress.

Members tailor the job to their personalities, interests, objectives, and constituent needs.[1] They engage in activities that better their chances for reelection. This strategy works, as the reelection rate for incumbents is over 90 percent.[2] They promote themselves and reach out to constituents by participating in events and public forums in their home districts. More recently, outreach has come to include using social media to connect with the public. Members of Congress take positions on issues that will be received favorably. They claim success for legislative activity that helps the district—and voters believe them.[3] Successful members excel at constituent service, helping people in the district deal with problems and negotiate the government bureaucracy.

Profile of Members

The vast majority of members of Congress are white males from middle- to upper-income groups. A majority are baby boomers, born between 1946 and 1964. The 111th Congress—which coincided with the administration of President Barack Obama, one of the nation’s youngest presidents, who took office at age forty-seven—was the oldest in history. In the 112th Congress, the average age of House members is fifty-seven and the average of senators is sixty-two. Most have a college education, and many have advanced degrees.[4]

Gender and Race

Since the 1980s, more women and members of diverse ethnic and racial groups have been elected, but they still are massively underrepresented. Ninety-one of the seats in the 112th Congress, or 16 percent, were held by women. These included seventy-four women in the House and seventeen in the Senate. A record number of forty-four African Americans served in the House, but there were none in the Senate. There were twenty-eight Hispanics in Congress—twenty-six in the House and two in the Senate. Thirteen Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and a single Native American were members of Congress.

Women and minority group representation in Congress can make a difference in the types of policy issues that are debated. Women members are more likely to focus on issues related to health care, poverty, and education. They have brought media attention to domestic violence and child custody. Members of minority groups raise issues pertinent to their constituents, such as special cancer risks experienced by Hispanics. The small number of women and minorities serving can hinder their ability to get legislation passed.[5]

Wealth

Members of Congress are a wealthy group. More than half of all members in 2009 were millionaires. More than fifty had net worths of over $10 million.[6] Members earn a salary of $174,000; leaders are compensated slightly more.[7] While this may seem like a lot of money, most members must maintain residences in Washington, DC, and their districts and must pay for trips back home. Some members take tremendous pay cuts to serve in Congress. Senator Maria Cantwell (D-WA) amassed a fortune of over $40 million as an executive for a Seattle software company before being elected in 2000.[8]

Occupations

For many members, serving in Congress is a career. Members of the House serve an average of nine years, or almost five terms. Senators average nearly eleven years, or almost two terms. Almost 75 percent of members seek reelection each cycle.[9] Members leave office because they seek more lucrative careers, such as in lobbying offices, or because they are ready to retire or are defeated.

Many members come from backgrounds other than politics, such as medicine, and bring experience from these fields to the lawmaking process. Business, law, and public service have been the dominant professions of members of Congress for decades.[10] Members who have come from nontraditional occupations include an astronaut, a magician, a musician, a professional baseball player, and a major league football player. Members also come from media backgrounds, including television reporters and an occasional sportscaster. Previous legislative experience is a useful qualification for members. Many were congressional staffers or state legislators in earlier careers.[11]

Members Making News

Because disseminating information and generating publicity are keys to governing, gaining reelection, and moving careers forward, many members of Congress hungrily seek media attention. They use publicity to rally public opinion behind their legislative proposals and to keep constituents abreast of their accomplishments. Media attention is especially important when constituents are deciding whether to retain or replace their member during elections or scandals.[12]

Members of Congress toe a thin line in their relations with the media. While garnering press attention and staying in the public eye may be a useful strategy, grabbing too much of the media spotlight can backfire, earning members a reputation for being more “show horse” than “work horse” and raising the ire of their colleagues.

Attracting national media attention is easier said than done for most members.[13] Members engage a variety of promotional tactics to court the press. They distribute press releases and hold press conferences. They use the Capitol’s studio facilities to tape television and radio clips that are distributed to journalists via the Internet. Rank-and-file members can increase their visibility by participating in events with prominent leaders. They can stage events or hold joint press conferences and photo ops.

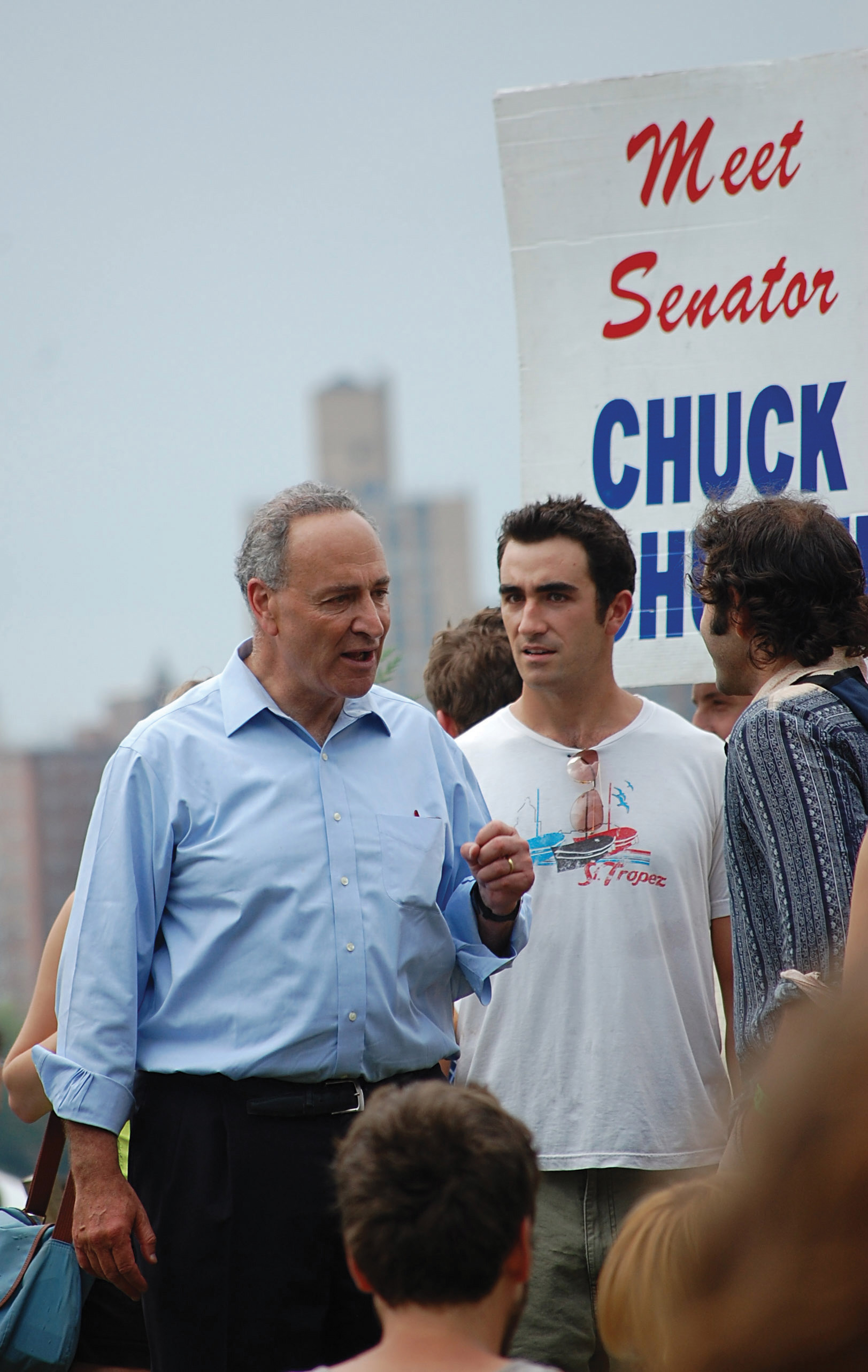

Testimony: Senator Chuck Schumer Meets the Press

One member of Congress who continually flirts with being overexposed in the media is Senator Charles “Chuck” Schumer (D-NY). Known as the consummate “show horse,” Schumer has been in public life and the media spotlight since being elected to the New York State Assembly at the age of twenty-three and then to the House of Representatives at twenty-nine. He became a US Senator in 1998 and has declared himself to be a “senator for life,” who does not have presidential aspirations. This claim gives him greater liberty to speak his mind in a manner that appeals to his New York constituency without worrying about pleasing a national audience. Schumer comes from modest means—his family owned a small pest extermination business—and has relied heavily on unpaid publicity to ensure his Senate seat. Over the years, the prolifically outspoken Schumer has earned a reputation for being one of the most notorious media hounds on Capitol Hill as well as one of the hardest working senators.

Schumer hails from Brooklyn, to which he attributes his affinity for speaking his mind. “That’s one of the benefits of being a Brooklynite. You’re a straight shooter with people, and people are back with you. And sometimes you offend people.”[14] While his Brooklynese may offend some, it generates headlines and plays well in New York, where he easily wins reelection campaigns.

Schumer’s communications staff is one of the busiest on Capitol Hill. Numerous press releases on a variety of issues affecting his home state and national policy might be issued in a single day. On the same day he announced legislation that would reverse plans to require passports at the Canadian border, called for the suspension of President Bush’s advisor Karl Rove’s security clearance for allegedly revealing the identity of CIA operative Valerie Plame, and publicized a list of twenty-five questions that should be asked of a Supreme Court nominee. This aggressive press strategy prompted his opponent in the 2004 election to pledge that he would “plant 25 trees to replace the trees killed last year to print Chuck Schumer’s press releases.”[15]

Schumer’s penchant for the media has made him the punch line for numerous jokes by fellow members of Congress. Former senator Bob Dole coined one of Capitol Hill’s favorite quips, “The most dangerous place in Washington is between Chuck Schumer and a microphone.”[16]

Senator Chuck Schumer is a high-profile member of Congress who regularly courts the media.

Members of Congress use new media strategies to inform the public, court the media, and gain publicity. All members have websites that publicize their activities and achievements. Some members make their views know through blog posts, including in online publications like TheHill.com and the Huffington Post. More than 300 members of Congress use Twitter to post brief announcements ranging from alerts about pending legislation to shout-outs to constituents who are celebrating anniversaries to Bible verses.

Congressional Staff

Members have personal staffs to help them manage their work load. They also work with committee staff who specialize in particular policy areas. Most Hill staffers are young, white, male, and ambitious. Most members maintain a staff in their home districts to handle constituent service.

Congressional staff has grown substantially since the 1970s as the number of policy issues and bills considered by Congress increased. Today, House personal staffs consist of an average of fourteen people. Senate staffs range in size from thirteen to seventy-one and average about thirty-four people.[17] As a result of staff expansion, each member has become the head of an enterprise—an organization of subordinates who form their own community that reflects the personality and strengths of the member.[18]

Congressional staffers have specialized responsibilities. Some staffers have administrative responsibilities, such as running the office and handling the member’s schedule. Others are responsible for assisting members with policy matters. Personal staffers work in conjunction with committee staffers to research and prepare legislation. They write speeches and position papers. Some act as brokers for members, negotiating support for bills and dealing with lobbyists. Staff influence over the legislative process can be significant, as staffers become experts on policies and take the lead on issues behind the scenes.[19]

Some staff members focus on constituent service. They spend a tremendous amount of time carefully crafting answers to the mountains of correspondence from constituents that arrives every day via snail mail, e-mail, fax, and phone. People write to express their views on legislation, to seek information about policies, and to express their pleasure or dissatisfaction about a member’s actions. They also contact members to ask for help with personal matters, such as immigration issues, or to alert members of potential public health menaces, such as faulty wiring in a large apartment building in the district.

Members of Congress resisted using e-mail to communicate until recent years. Members were not assigned e-mail addresses until 1995. Despite the daunting flood of messages, e-mail has helped congressional offices communicate with constituents efficiently. While the franking privilege, members’ ability to post mail without cost, is still important, e-mail has reduced the significance of this perk.

All members of Congress have press secretaries to coordinate their interactions with the media. They bring a journalistic perspective to congressional offices, acting as consultants in devising media strategies. In recent years, the press secretary’s job has expanded to include using social media to publicize the member’s actions and positions. A press secretary for a publicity-seeking member who faces tough reelection bids constantly courts the media, making personal contacts, writing press releases, staging photo ops and events, and helping the member prepare video and audio interviews. The press secretary constantly updates the member’s Facebook and Twitter messages and YouTube videos. A press secretary for a member in a secure seat who prefers a low-key media presence concentrates on maintaining contact with constituents through newsletters and the member’s website.

Key Takeaways

In recent years, the membership of Congress has become increasingly diverse, as more women and minority group members have been elected. Still, the dominant profile of the member of Congress is an older, white male. In addition to their constitutional duties, members of Congress engage in a host of other activities, many of which are related to getting reelected. Members strive to maintain close connections with their constituents while serving in Washington. They seek to publicize their activities through the mainstream press as well as social media. Congressional staffers aid members in keeping abreast of policy issues, performing constituent service, and dealing with the press.

Candela Citations

- 21st Century American Government. Authored by: Anonymous. Provided by: Lardbucket. Located at: http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/21st-century-american-government-and-politics/s16-08-members-of-congress.html. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Memorial for U.S. Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords. Authored by: Wayno Guerrini. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Memorial_in_front_of_office_of_Gabrielle_Giffords.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Senator Chuck Schumer. Authored by: Zoe. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/_lovenothing/3851657362/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Richard Fenno, Home Style (New York: Longman Classics, 2003). ↵

- Gary Jacobson, The Politics of Congressional Elections, 5th ed. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2002). ↵

- Alan I. Abramowitz, “Name Familiarity, Reputation, and the Incumbency Effect in a Congressional Election,” Western Political Quarterly 28 (September 1975): 668–84; Morris P. Fiorina, Congress: Keystone of the Washington Establishment (New Haven, CT: Yale, 1977); David R. Mayhew, Congress: The Electoral Connection (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1974). ↵

- Jennifer E. Manning, “Membership of the 112th Congress: A Profile,” CRS Report for Congress (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, March 1, 2011). ↵

- Michele L. Swers, The Difference Women Make (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002). ↵

- Albert Bozzo, “Members of U.S. Congress Get Richer Despite Sour Economy,” CNBC, November 17, 2010, accessed December 12, 2010. ↵

- Ida Brudnick and Eric Peterson, Congressional Pay and Perks (Alexandria, VA: TheCapitolNet.com), 2010. ↵

- Amy Keller, “The Roll Call 50 Richest,” Roll Call, September 8, 2003. ↵

- Gary Jacobson, The Politics of Congressional Elections, 5th ed. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2002). ↵

- David T. Canon, Actors, Athletes, and Astronauts(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990). ↵

- Mildred L. Amer, “Membership of the 108th Congress: A Profile,” CRS Report for Congress, May, 2003. ↵

- R. Douglas Arnold, Congress, the Press, and Political Accountability (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004). ↵

- Timothy E. Cook,Making Laws & Making News (Washington, DC: Brookings, 1989). ↵

- Mark Leibovich, “The Senator Has the Floor,”Washington Post, August 15, 2005: C01. ↵

- Mark Leibovich, “The Senator Has the Floor,” Washington Post, August 15, 2005: C01. ↵

- Miranda, Manuel, “Behind Schumer’s Ill Humor,” The Wall Street Journal, August 3, 2005, Editorial Page. ↵

- Roger H. Davidson and Walter J. Oleszek, Congress and Its Members, 8th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2002). ↵

- Robert H. Salisbury and Kenneth A. Shepsle, “U.S. Congressman as Enterprise,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 6, no. 4 (November 1981): 559–76. ↵

- Susan Webb Hammond, “Recent Research on Legislative Staffs,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 21, no. 4 (November 1996): 543–76. ↵