Aggregate Demand Curve

Aggregate demand (AD) refers to total spending in an economy on domestic goods and services. (Strictly speaking, AD is what economists call total planned expenditure. You’ll learn about this in more detail in the Keynesian module.) It includes all four components of spending: consumption expenditure, investment expenditure, government expenditure, and net export expenditure (exports minus imports). This demand is determined by a number of factors, but one of them is the aggregate price level. The aggregate demand (AD) curve shows the total spending on domestic goods and services at each price level.

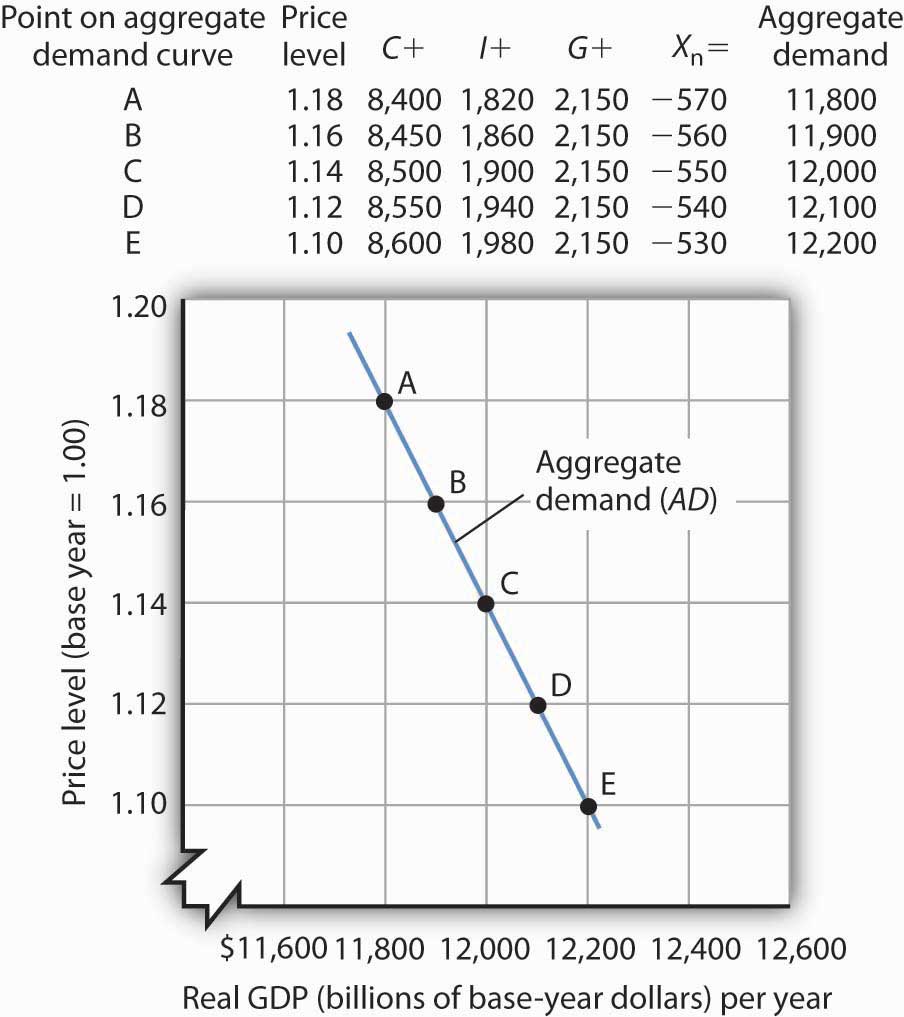

Figure 2 presents an aggregate demand (AD) curve. Just like the aggregate supply curve, the horizontal axis shows real GDP and the vertical axis shows the price level. The AD curve is downward sloping from left to right, which means that a decrease in the aggregate price level leads to an increase in the amount of total spending on domestic goods and services. Even though the AD curve looks like a microeconomic demand curve, it doesn’t operate the same way. Rather, the reasons behind this negative relationship are related to how changes in the price level affect the different components of aggregate demand. Recall that aggregate demand consists of consumption spending (C), investment spending (I), government spending (G), and spending on exports (X) minus imports (M): C + I + G + X – M.

Figure 2. The Aggregate Demand Curve. Aggregate demand (AD) slopes down, showing that, as the price level rises, the amount of total spending on domestic goods and services declines.

There are three specific reasons for why AD curves are downward sloping. These are the wealth effect, the interest rate effect and the foreign price effect. Each of them tends to affect a different component of aggregate demand.

The Slope of the Aggregate Demand Curve

Firms face four sources of demand: households (personal consumption), other firms (investment), government agencies (government purchases), and foreign markets (net exports). Aggregate demand is the relationship between the total quantity of goods and services demanded (from all the four sources of demand) and the price level, all other determinants of spending unchanged. The aggregate demand curve is a graphical representation of aggregate demand.

We will use the implicit price deflator as our measure of the price level; the aggregate quantity of goods and services demanded is measured as real GDP. The table in Figure 7.1 “Aggregate Demand” gives values for each component of aggregate demand at each price level for a hypothetical economy. Various points on the aggregate demand curve are found by adding the values of these components at different price levels. The aggregate demand curve for the data given in the table is plotted on the graph in Figure 7.1 “Aggregate Demand.” At point A, at a price level of 1.18, $11,800 billion worth of goods and services will be demanded; at point C, a reduction in the price level to 1.14 increases the quantity of goods and services demanded to $12,000 billion; and at point E, at a price level of 1.10, $12,200 billion will be demanded.

Figure 7.1. Aggregate Demand. An aggregate demand curve (AD) shows the relationship between the total quantity of output demanded (measured as real GDP) and the price level (measured as the implicit price deflator). At each price level, the total quantity of goods and services demanded is the sum of the components of real GDP, as shown in the table. There is a negative relationship between the price level and the total quantity of goods and services demanded, all other things unchanged.

The negative slope of the aggregate demand curve suggests that it behaves in the same manner as an ordinary demand curve. But we cannot apply the reasoning we use to explain downward-sloping demand curves in individual markets to explain the downward-sloping aggregate demand curve. There are two reasons for a negative relationship between price and quantity demanded in individual markets. First, a lower price induces people to substitute more of the good whose price has fallen for other goods, increasing the quantity demanded. Second, the lower price creates a higher real income. This normally increases quantity demanded further.

Neither of these effects is relevant to a change in prices in the aggregate. When we are dealing with the average of all prices—the price level—we can no longer say that a fall in prices will induce a change in relative prices that will lead consumers to buy more of the goods and services whose prices have fallen and less of the goods and services whose prices have not fallen. The price of corn may have fallen, but the prices of wheat, sugar, tractors, steel, and most other goods or services produced in the economy are likely to have fallen as well.

Furthermore, a reduction in the price level means that it is not just the prices consumers pay that are falling. It means the prices people receive—their wages, the rents they may charge as landlords, the interest rates they earn—are likely to be falling as well. A falling price level means that goods and services are cheaper, but incomes are lower, too. There is no reason to expect that a change in real income will boost the quantity of goods and services demanded—indeed, no change in real income would occur. If nominal incomes and prices all fall by 10%, for example, real incomes do not change.

1. Wealth Effect

Why, then, does the aggregate demand curve slope downward? One reason for the downward slope of the aggregate demand curve lies in the relationship between real wealth (the stocks, bonds, and other assets that people have accumulated) and consumption (one of the four components of aggregate demand). When the price level falls, the real value of wealth increases—it packs more purchasing power. For example, if the price level falls by 25%, then $10,000 of wealth could purchase more goods and services than it would have if the price level had not fallen. An increase in wealth will induce people to increase their consumption. The consumption component of aggregate demand will thus be greater at lower price levels than at higher price levels. The tendency for a change in the price level to affect real wealth and thus alter consumption is called the wealth effect; it suggests a negative relationship between the price level and the real value of consumption spending.

2. Interest Rate Effect

A second reason the aggregate demand curve slopes downward lies in the relationship between interest rates and investment. A lower price level lowers the demand for money, because less money is required to buy a given quantity of goods. What economists mean by money demand will be explained in more detail in a later chapter. But, as we learned in studying demand and supply, a reduction in the demand for something, all other things unchanged, lowers its price. In this case, the “something” is money and its price is the interest rate. A lower price level thus reduces interest rates. Lower interest rates make borrowing by firms to build factories or buy equipment and other capital more attractive. A lower interest rate means lower mortgage payments, which tends to increase investment in residential houses. Investment thus rises when the price level falls. The tendency for a change in the price level to affect the interest rate and thus to affect the quantity of investment demanded is called the interest rate effect. John Maynard Keynes, a British economist whose analysis of the Great Depression and what to do about it led to the birth of modern macroeconomics, emphasized this effect. For this reason, the interest rate effect is sometimes called the Keynes effect.

3. Exchange Rate Effect

A third reason for the rise in the total quantity of goods and services demanded as the price level falls can be found in changes in the net export component of aggregate demand. All other things unchanged, a lower price level in an economy reduces the prices of its goods and services relative to foreign-produced goods and services. A lower price level makes that economy’s goods more attractive to foreign buyers, increasing exports. It will also make foreign-produced goods and services less attractive to the economy’s buyers, reducing imports. The result is an increase in net exports. The international trade effect is the tendency for a change in the price level to affect net exports.

To get a better understanding of how the foreign exchange market works please read the following pages:

Taken together, then, a fall in the price level means that the quantities of consumption, investment, and net export components of aggregate demand may all rise. Since government purchases are determined through a political process, we assume there is no causal link between the price level and the real volume of government purchases. Therefore, this component of GDP does not contribute to the downward slope of the curve.

In general, a change in the price level, with all other determinants of aggregate demand unchanged, causes a movement along the aggregate demand curve. A movement along an aggregate demand curve is a change in the aggregate quantity of goods and services demanded. A movement from point A to point B on the aggregate demand curve in Figure 7.1 “Aggregate Demand” is an example. Such a change is a response to a change in the price level.

Notice that the axes of the aggregate demand curve graph are drawn with a break near the origin to remind us that the plotted values reflect a relatively narrow range of changes in real GDP and the price level. We do not know what might happen if the price level or output for an entire economy approached zero. Such a phenomenon has never been observed.

Changes in Aggregate Demand

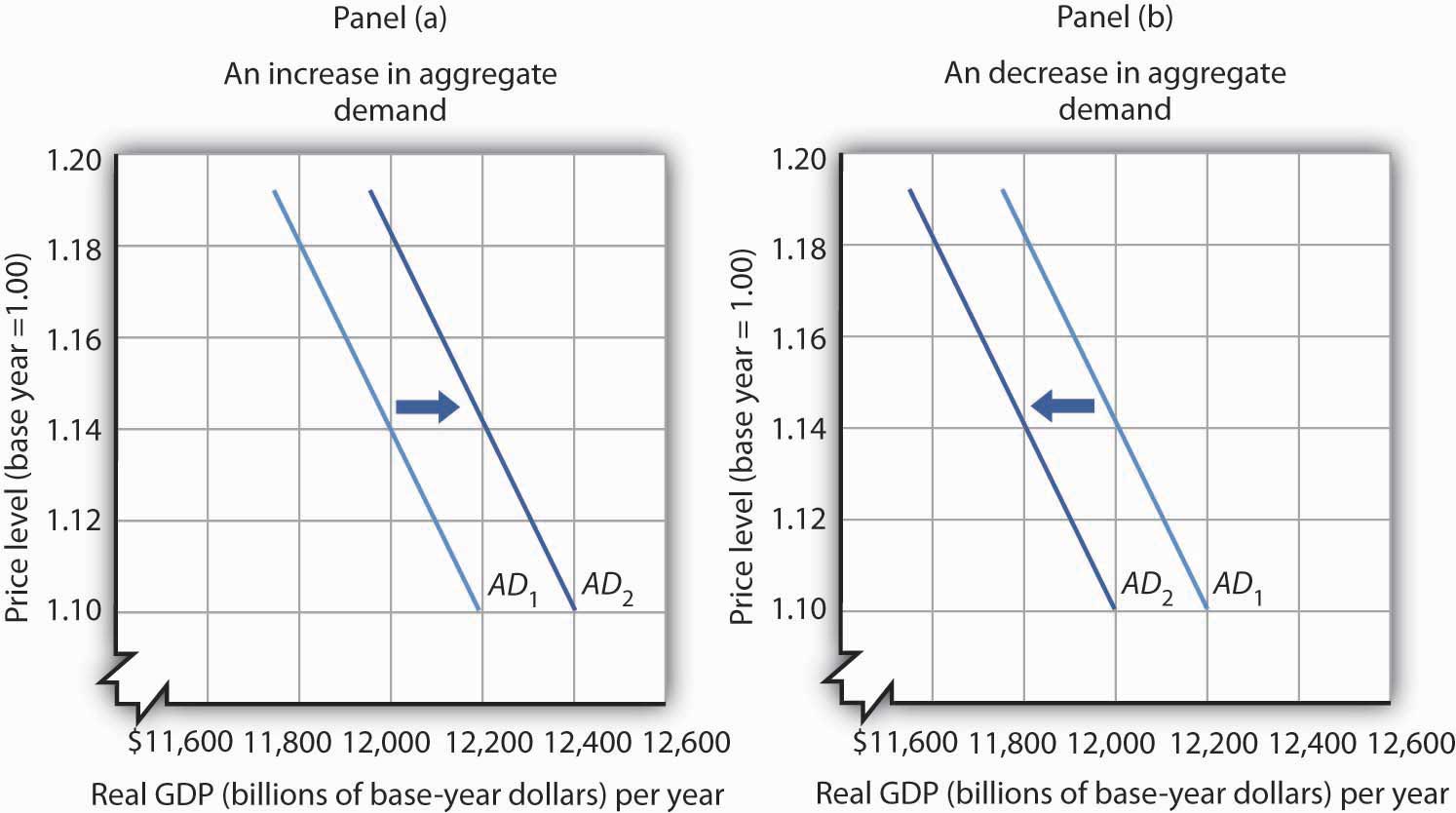

Aggregate demand changes in response to a change in any of its components. An increase in the total quantity of consumer goods and services demanded at every price level, for example, would shift the aggregate demand curve to the right. A change in the aggregate quantity of goods and services demanded at every price level is a change in aggregate demand, which shifts the aggregate demand curve. Increases and decreases in aggregate demand are shown in Figure 7.2 “Changes in Aggregate Demand.”

Figure 7.2. Changes in Aggregate Demand. An increase in consumption, investment, government purchases, or net exports shifts the aggregate demand curve AD1 to the right as shown in Panel (a). A reduction in one of the components of aggregate demand shifts the curve to the left, as shown in Panel (b).

What factors might cause the aggregate demand curve to shift? Each of the components of aggregate demand is a possible aggregate demand shifter. We shall look at some of the events that can trigger changes in the components of aggregate demand and thus shift the aggregate demand curve.

Changes in Consumption

Several events could change the quantity of consumption at each price level and thus shift aggregate demand. One determinant of consumption is consumer confidence. If consumers expect good economic conditions and are optimistic about their economic prospects, they are more likely to buy major items such as cars or furniture. The result would be an increase in the real value of consumption at each price level and an increase in aggregate demand. In the second half of the 1990s, sustained economic growth and low unemployment fueled high expectations and consumer optimism. Surveys revealed consumer confidence to be very high. That consumer confidence translated into increased consumption and increased aggregate demand. In contrast, a decrease in consumption would accompany diminished consumer expectations and a decrease in consumer confidence, as happened after the stock market crash of 1929. The same problem has plagued the economies of most Western nations in 2008 as declining consumer confidence has tended to reduce consumption. A survey by the Conference Board in September of 2008 showed that just 13.5% of consumers surveyed expected economic conditions in the United States to improve in the next six months. Similarly pessimistic views prevailed in the previous two months. That contributed to the decline in consumption that occurred in the third quarter of the year.

Another factor that can change consumption and shift aggregate demand is tax policy. A cut in personal income taxes leaves people with more after-tax income, which may induce them to increase their consumption. The federal government in the United States cut taxes in 1964, 1981, 1986, 1997, and 2003; each of those tax cuts tended to increase consumption and aggregate demand at each price level.

In the United States, another government policy aimed at increasing consumption and thus aggregate demand has been the use of rebates in which taxpayers are simply sent checks in hopes that those checks will be used for consumption. Rebates have been used in 1975, 2001, and 2008. In each case the rebate was a one-time payment. Careful studies by economists of the 1975 and 2001 rebates showed little impact on consumption. Final evidence on the impact of the 2008 rebates is not yet in, but early results suggest a similar outcome. In a subsequent chapter, we will investigate arguments about whether temporary increases in income produced by rebates are likely to have a significant impact on consumption.

Transfer payments such as welfare and Social Security also affect the income people have available to spend. At any given price level, an increase in transfer payments raises consumption and aggregate demand, and a reduction lowers consumption and aggregate demand.

Changes in Investment

Investment is the production of new capital that will be used for future production of goods and services. Firms make investment choices based on what they think they will be producing in the future. The expectations of firms thus play a critical role in determining investment. If firms expect their sales to go up, they are likely to increase their investment so that they can increase production and meet consumer demand. Such an increase in investment raises the aggregate quantity of goods and services demanded at each price level; it increases aggregate demand.

Changes in interest rates also affect investment and thus affect aggregate demand. We must be careful to distinguish such changes from the interest rate effect, which causes a movement along the aggregate demand curve. A change in interest rates that results from a change in the price level affects investment in a way that is already captured in the downward slope of the aggregate demand curve; it causes a movement along the curve. A change in interest rates for some other reason shifts the curve. We examine reasons interest rates might change in another chapter.

Investment can also be affected by tax policy. One provision of the Job and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 was a reduction in the tax rate on certain capital gains. Capital gains result when the owner of an asset, such as a house or a factory, sells the asset for more than its purchase price (less any depreciation claimed in earlier years). The lower capital gains tax could stimulate investment, because the owners of such assets know that they will lose less to taxes when they sell those assets, thus making assets subject to the tax more attractive.

Changes in Government Purchases

Any change in government purchases, all other things unchanged, will affect aggregate demand. An increase in government purchases increases aggregate demand; a decrease in government purchases decreases aggregate demand.

Many economists argued that reductions in defense spending in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 tended to reduce aggregate demand. Similarly, increased defense spending for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq increased aggregate demand. Dramatic increases in defense spending to fight World War II accounted in large part for the rapid recovery from the Great Depression.

Changes in Net Exports

A change in the value of net exports at each price level shifts the aggregate demand curve. A major determinant of net exports is foreign demand for a country’s goods and services; that demand will vary with foreign incomes. An increase in foreign incomes increases a country’s net exports and aggregate demand; a slump in foreign incomes reduces net exports and aggregate demand. For example, several major U.S. trading partners in Asia suffered recessions in 1997 and 1998. Lower real incomes in those countries reduced U.S. exports and tended to reduce aggregate demand.

Exchange rates also influence net exports, all other things unchanged. A country’s exchange rate is the price of its currency in terms of another currency or currencies. A rise in the U.S. exchange rate means that it takes more Japanese yen, for example, to purchase one dollar. That also means that U.S. traders get more yen per dollar. Since prices of goods produced in Japan are given in yen and prices of goods produced in the United States are given in dollars, a rise in the U.S. exchange rate increases the price to foreigners for goods and services produced in the United States, thus reducing U.S. exports; it reduces the price of foreign-produced goods and services for U.S. consumers, thus increasing imports to the United States. A higher exchange rate tends to reduce net exports, reducing aggregate demand. A lower exchange rate tends to increase net exports, increasing aggregate demand.

Foreign price levels can affect aggregate demand in the same way as exchange rates. For example, when foreign price levels fall relative to the price level in the United States, U.S. goods and services become relatively more expensive, reducing exports and boosting imports in the United States. Such a reduction in net exports reduces aggregate demand. An increase in foreign prices relative to U.S. prices has the opposite effect.

The trade policies of various countries can also affect net exports. A policy by Japan to increase its imports of goods and services from India, for example, would increase net exports in India.

This table summarizes the reasons given here for changes in aggregate demand.

| Table 1. Determinants of Aggregate Demand | |

|---|---|

| Reasons for a Decrease in Aggregate Demand | Reasons for an Increase in Aggregate Demand |

Consumption

|

Consumption

|

Investment

|

Investment

|

Government

|

Government

|

Net Exports

|

Net Exports

|

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Potential output is the level of output an economy can achieve when labor is employed at its natural level. When an economy fails to produce at its potential, the government or the central bank may try to push the economy toward its potential.

- The aggregate demand curve represents the total of consumption, investment, government purchases, and net exports at each price level in any period. It slopes downward because of the wealth effect on consumption, the interest rate effect on investment, and the international trade effect on net exports.

- The aggregate demand curve shifts when the quantity of real GDP demanded at each price level changes.

- The multiplier is the number by which we multiply an initial change in aggregate demand to obtain the amount by which the aggregate demand curve shifts at each price level as a result of the initial change.

Learning Objectives

- Define and explain the aggregate supply curve and the economic behavior behind it

- Compare and contrast the short run and long run aggregate supply curves

- Define and explain the aggregate demand curve and the economic behavior behind it

- Differentiate between the two concepts of aggregate demand and aggregate supply

Aggregate Supply

The Aggregate Demand-Aggregate Supply model is designed to answer the questions of what determines the level of economic activity in the economy (i.e. what determines real GDP and employment), and what causes economic activity to speed up or slow down.

We can begin to answer these questions if we think about the concept of the aggregate production function, which we introduced in the context of economic growth. The aggregate production function shows the relationship between the resources (or factors of production) the economy has (e.g. labor, capital, technology, etc.) and the amount of output (i.e. real GDP) that can be produced. If all resources are fully employed, the resulting output is called Potential GDP. (Over time, as the economy obtains more resources as the labor force and capital stock grow and as technology improves, the economy produces more GDP. We have described this process as economic growth.)

Firms make decisions about what quantity of output to supply based on the profits they expect to earn. Profits, in turn, are also determined by the price of the outputs the firm sells and by the price of the inputs, like labor or raw materials, the firm needs to buy.

The previous paragraph included a critical assumption: full employment of resources. Why wouldn’t all resources be fully employed? Recall that when we discussed cyclical unemployment, we pointed out that wages are often sticky, that is, they don’t respond immediately to changes in demand for labor. The same thing may be true of other input prices. Let’s think about that in the context of an aggregate supply curve, showing the relationship between the aggregate price level and real GDP.

Aggregate supply (AS) refers to the total quantity of output (i.e. real GDP) firms will produce. The aggregate supply (AS) curve shows the total quantity of output firms will produce and sell (i.e, real GDP) at each aggregate price level, holding the price of inputs fixed.

Recall that the aggregate price level is an average of the prices of outputs in the economy. A decrease in the price level means that firms would like to reduce the wage rate they pay so they can maintain their profits. If wages are sticky downwards, labor becomes too expensive to keep fully employed, so firms layoff workers. (Economists would say that the real wage (W/P) is too high.) With fewer workers employed, firms produce less output and real GDP decreases. In short, when wages are sticky in response to changes in demand, then a lower aggregate price level corresponds to a lower level of real GDP. Similarly, an increase in the price level means that firms would like to raise wages, but it wages are sticky, labor becomes cheap so firms increase employment (or work hours) and real GDP increases.

Figure 1 shows an aggregate supply curve. In the following paragraphs, we will walk through the elements of the diagram one at a time: the horizontal and vertical axes, the aggregate supply curve itself, and the meaning of the potential GDP vertical line.

Figure 1. The Aggregate Supply Curve. Aggregate supply (AS) slopes up, because as the price level for outputs rises, with the price of inputs remaining fixed, firms have an incentive to produce more and to earn higher profits. The potential GDP line shows the maximum that the economy can produce with full employment of workers and physical capital.

The horizontal axis of the diagram shows real GDP—that is, the level of GDP adjusted for inflation. The vertical axis shows the aggregate price level. As the price level rises, the aggregate quantity of goods and services produced rises as well. Why? The price level shown on the vertical axis represents the average price for final goods or outputs purchased in the economy, i.e. the GDP deflator. It is not the price level for intermediate goods and services that are inputs to production. Thus, the AS curve describes how suppliers will react to a higher price level for outputs of goods and services, while holding the prices of inputs like labor and energy constant. If firms across the economy face a situation where the price level of what they produce and sell is rising, but their costs of production are not rising, then the lure of higher profits will induce them to expand production.

The slope of an AS curve changes from nearly flat at its far left to nearly vertical at its far right. At the far left of the aggregate supply curve, the level of output in the economy is far below potential GDP, which is defined as the quantity that an economy can produce by fully employing its resources of labor, physical capital, and technology, in the context of its existing market and legal institutions. At these relatively low levels of output, levels of unemployment are high, and many factories are running only part-time, or have closed their doors. In this situation, a relatively small increase in the prices of the outputs that businesses sell—while making the assumption of no rise in input prices—can encourage a considerable surge in real GDP because so many workers and factories are ready to swing into production.

As the quantity produced increases, however, certain firms and industries will start running into limits: perhaps nearly all of the expert workers in a certain industry will have jobs or factories in certain geographic areas or industries will be running at full speed. In the intermediate area of the AS curve, a higher price level for outputs continues to encourage a greater quantity of output—but as the increasingly steep upward slope of the aggregate supply curve shows, the increase in GDP in response to a given rise in the price level will not be quite as large.

WHY DOES AS CROSS POTENTIAL GDP?

The aggregate supply curve is typically drawn to cross the potential GDP line. This shape may seem puzzling: How can an economy produce at an output level which is higher than its “potential” or “full employment” GDP? The economic intuition here is that if prices for outputs were high enough, producers would make fanatical efforts to produce: all workers would be on double-overtime, all machines would run 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Such hyper-intense production would go beyond using potential labor and physical capital resources fully, to using them in a way that is not sustainable in the long term. Thus, it is indeed possible for production to sprint above potential GDP, but only in the short run.

At the far right, the aggregate supply curve becomes nearly vertical. At this quantity, higher prices for outputs cannot encourage additional output, because even if firms want to expand output, the inputs of labor and machinery in the economy are fully employed. In this example, the vertical line in the exhibit shows that potential GDP occurs at a total output of 9,500. When an economy is operating at its potential GDP, machines and factories are running at capacity, and the unemployment rate is relatively low—at the natural rate of unemployment. For this reason, potential GDP is sometimes also called full-employment GDP.

Try It

Defining SRAS and LRAS

If we define the short run as the period of time that wages are sticky, then we can describe the positive relationship between P & Q as the short run aggregate supply (SRAS) curve, shown above in Figure 1 as AS.

In the long run, however, all wages and prices are fully flexible. As a consequence, all resources will be fully employed and real GDP will equal potential, regardless of the price level. Thus, in the long run, real GDP will be independent of the price level, and the long run aggregate supply (LRAS) curve will be a vertical line at potential (or the full employment level of) GDP. This can be seen on a graph as potential GDP (as in Figure 1) or as LRAS.

Try It

Candela Citations

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Building a Model of Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/https://cnx.org/contents/vEmOH-_p@4.44:7tt98uaX@4/Building-a-Model-of-Aggregate--098e-4b3c-a1d9-7eb593a2cb31@10.49:2/Macroeconomics. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/bc498e1f-efe9-43a0-8dea-d3569ad09a82@4.44