Learning Outcomes

- Use the Pythagorean Theorem to relate the sides of a right triangle

- Find the distance between two points on the coordinate plane

- Find the coordinates of the point half way between two points on the coordinate plane

- Give the equation of a circle given its center and radius.

- Draw angles in standard position.

- Convert between degrees and radians.

- Find coterminal angles.

- Find the length of a circular arc.

- Find the area of a sector of a circle.

- Use linear and angular speed to describe motion on a circular path.

Circles and Triangles

The Utility of the Pythagorean Theorem

Our main focus in this course will be trigonometry, or the study of triangles. We begin however with an exploration of circles. While this may seem surprising, we will see how circles and triangles are deeply connected and how our understanding of one informs our knowledge of the other.

To make things extra circular (see what I did there?) we will start our discussion of circles with that famous theorem about right triangles, the Pythagorean Theorem.

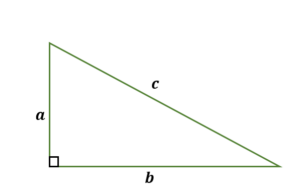

The Pythagorean Theorem: In a right triangle with side lengths [latex]a[/latex], [latex]b[/latex] and [latex]c[/latex], where [latex]c[/latex] is the hypotenuse, [latex]a^2 + b^2 = c^2[/latex]

Figure 1

It is important to note that the Pythagorean Theorem only holds for right triangles.

Try It

We will see that the Pythagorean Theorem pops up throughout this course. Let’s start by using it to derive what is known as the distance formula. The distance formula gives us a way of computing the distance between two points on the coordinate plane. In Figure 2 below, we have two points, [latex](x_1, y_1)[/latex] and [latex](x_2, y_2)[/latex]. We would like a way to compute the distance between these two points.

We can leverage the fact that we are working on the coordinate grid by drawing a right triangle with legs parallel to the [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex] axes and hypotenuse connecting the two points as shown in Figure 3 below.

To use the Pythagorean Theorem, we need to know the lengths of two of the three sides of our right triangle. We can compute the lengths of the two legs of the triangle using the change in the [latex]x[/latex]-values for the horizontal leg and the change in the [latex]y[/latex]-values for the vertical leg as shown in Figure 4 below.

Notice that distances must always be non-negative, so a cautious reader like yourself might be concerned that we might need to take the absolute value of the difference of the values. Normally, you would be correct in this concern but this will become irrelevant in a minute when we apply the Pythagorean Theorem since it requires that we square the lengths of the sides of the triangle.

Applying the Pythagorean Theorem to our triangle, we have:

[latex]d^2 = (x_2-x_1)^2 + (y_2-y_1)^2[/latex].

For the cautious reader who was worried about negative lengths for the legs of the triangle, notice that when we square the differences in the [latex]x[/latex] or [latex]y[/latex]-values, the negative sign disappears.

Since we are hoping to solve for [latex]d[/latex], we can take the square root of both sides of this equation. Giving us:

[latex]d = \pm\sqrt{ (x_2-x_1)^2 + (y_2-y_1)^2}[/latex].

Since [latex]d[/latex] is a distance, we can ignore the negative answer. Thus, we have derived the distance formula as summarized below:

Try It

Since we just found the formula for the distance between two points on the coordinate plane, it might also be useful to find the coordinates of the point halfway between any two points on the coordinate plane. This is often called the midpoint formula.

This formula comes from the fact that the midpoint is located exactly halfway between the [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex]-coordinates of the given points. We can find that halfway point by computing the average (mean) of the two values. Thus, the halfway point in the [latex]x[/latex]-direction is given by [latex]\frac{x_1 + x_2}{2}[/latex], and a similar process will work for the halfway point in the [latex]y[/latex]-direction.

Try It

The Equation of a Circle

Let’s return to the circle. You might recall that a

is a geometric object defined by the set of all points that are a fixed distance (called the radius) away from a given point (called the center). We would like to find the equation of a circle given its center and radius.

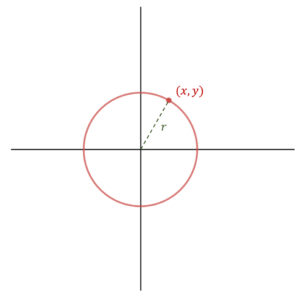

Let’s begin with finding the equation of a circle with radius [latex]r[/latex] centered at the origin. In Figure 6 below, we have drawn such a circle and labeled an arbitrary point on it [latex](x, y)[/latex].

By dropping a line from the point [latex](x, y)[/latex] perpendicular to the [latex]x[/latex]-axis, we create a right triangle as shown in Figure 7:

We know the lengths of the legs of the right triangle are [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex] since those are the distances from the origin to the [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex]-coordinates of the point. Furthermore, we know the hypotenuse of the triangle is [latex]r[/latex] since it is the radius of the circle. Thus, using the Pythagorean Theorem, we see that

[latex]x^2 + y^2 = r^2[/latex].

This is the equation of the circle centered at the origin and with radius [latex]r[/latex]. Notice that this equation does not have the form [latex]y=f(x)[/latex]. While it is possible to get [latex]y[/latex] by itself on one side of the equation, the format given above is the standard way of writing the equation of a circle.

Recalling that a function must pass the vertical line test, we also note that this circle is most definitely not a function. Therefore, it is less important to write it in the form [latex]y=f(x)[/latex]. Nevertheless, it is important to note that every point that is on the circle will satisfy the equation above.

What if the circle is not centered at the origin? We will use a similar process to find the equation of such a circle. Suppose our circle is centered at the point [latex](h, k)[/latex] and has radius [latex]r[/latex] as shown in Figure 8:

Just as before, we can create a right triangle with legs perpendicular to the [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex] axes and hypotenuse given by the radius connecting the center to the point [latex](x,y)[/latex]. We can then find the lengths of the legs by computing the difference of the [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex]-coordinates disregarding the sign if it happens to be a negative difference.

Finally, using the Pythagorean Theorem again, we get the following equation:

[latex](x-h)^2 +(y-k)^2 = r^2.[/latex]

This is the desired equation.

Try It

Try It

Try It

Angles

A golfer swings to hit a ball over a sand trap and onto the green. An airline pilot maneuvers a plane toward a narrow runway. A dress designer creates the latest fashion. What do they all have in common? They all work with angles, and so do all of us at one time or another. Sometimes we need to measure angles exactly with instruments. Other times we estimate them or judge them by eye. Either way, the proper angle can make the difference between success and failure in many undertakings. In this section, we will examine properties of angles.

Draw angles in standard position

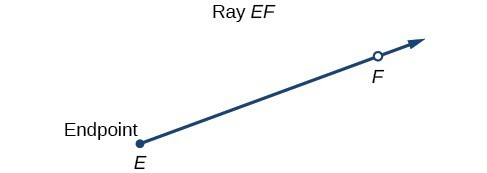

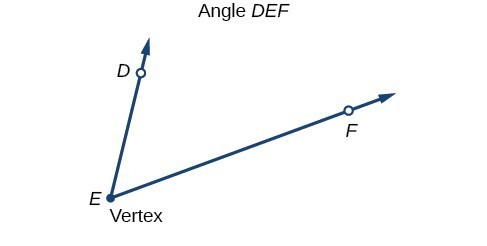

Properly defining an angle first requires that we define a ray. A ray consists of one point on a line and all points extending in one direction from that point. The first point is called the endpoint of the ray. We can refer to a specific ray by stating its endpoint and any other point on it. The ray in Figure 1 can be named as ray EF, or in symbolic form [latex]\overrightarrow{EF}[/latex].

Figure 9

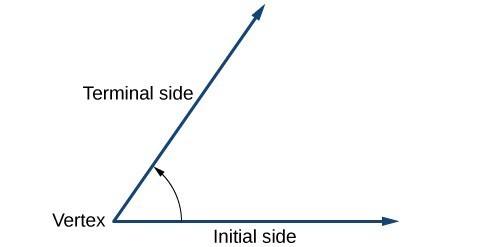

An angle is the union of two rays having a common endpoint. The endpoint is called the vertex of the angle, and the two rays are the sides of the angle. The angle in Figure 2 is formed from [latex]\overrightarrow{ED}[/latex] and [latex]\overrightarrow{EF}[/latex]. Angles can be named using a point on each ray and the vertex, such as angle [latex]{DEF}[/latex], or in symbol form [latex]\angle{DEF}[/latex].

Figure 10

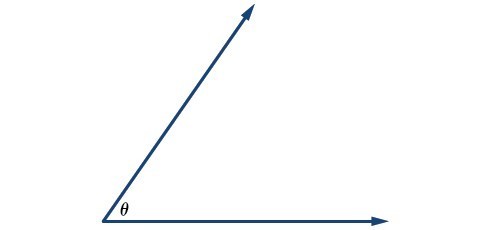

Greek letters are often used as variables for the measure of an angle. The table below is a list of Greek letters commonly used to represent angles, and a sample angle is shown in Figure 2.

| [latex]\theta[/latex] | [latex]\phi \text{ or }\varphi[/latex] | [latex]\alpha[/latex] | [latex]\beta[/latex] | [latex]\gamma[/latex] |

| theta | phi | alpha | beta | gamma |

Figure 11. Angle theta, shown as [latex]\angle \theta[/latex]

Figure 12

Angle creation is a dynamic process. We start with two rays lying on top of one another. We leave one fixed in place, and rotate the other. The fixed ray is the initial side, and the rotated ray is the terminal side. In order to identify the different sides, we indicate the rotation with a small arc and arrow close to the vertex as in Figure 4.

The following video provides an illustration of angles in standard position.

As we discussed at the beginning of the section, there are many applications for angles, but in order to use them correctly, we must be able to measure them. The measure of an angle is the amount of rotation from the initial side to the terminal side. Probably the most familiar unit of angle measurement is the degree. One degree is [latex]\frac{1}{360}[/latex] of a circular rotation, so a complete circular rotation contains 360 degrees. An angle measured in degrees should always include the unit “degrees” after the number, or include the degree symbol °. For example, 90 degrees = 90°.

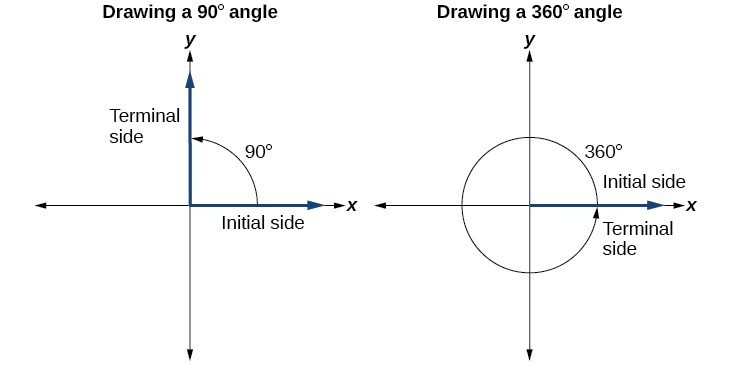

Figure 13

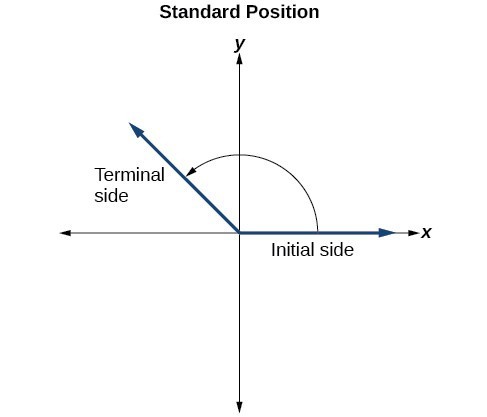

To formalize our work, we will begin by drawing angles on an x–y coordinate plane. Angles can occur in any position on the coordinate plane, but for the purpose of comparison, the convention is to illustrate them in the same position whenever possible. An angle is in standard position if its vertex is located at the origin, and its initial side extends along the positive x-axis.

If the angle is measured in a counterclockwise direction from the initial side to the terminal side, the angle is said to be a positive angle. If the angle is measured in a clockwise direction, the angle is said to be a negative angle.

Figure 14

Drawing an angle in standard position always starts the same way—draw the initial side along the positive x-axis. To place the terminal side of the angle, we must calculate the fraction of a full rotation the angle represents. We do that by dividing the angle measure in degrees by 360°. For example, to draw a 90° angle, we calculate that [latex]\frac{90^\circ }{360^\circ }=\frac{1}{4}[/latex]. So, the terminal side will be one-fourth of the way around the circle, moving counterclockwise from the positive x-axis. To draw a 360° angle, we calculate that [latex]\frac{360^\circ }{360^\circ }=1[/latex]. So the terminal side will be 1 complete rotation around the circle, moving counterclockwise from the positive x-axis. In this case, the initial side and the terminal side overlap.

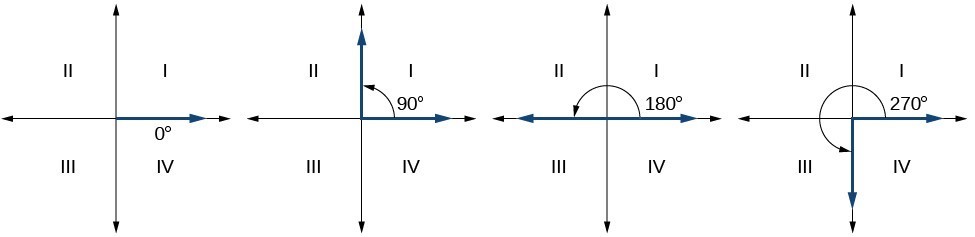

Since we define an angle in standard position by its terminal side, we have a special type of angle whose terminal side lies on an axis, a quadrantal angle. This type of angle can have a measure of 0°, 90°, 180°, 270° or 360°.

Figure 15. Quadrantal angles have a terminal side that lies along an axis. Examples are shown.

A GENERAL NOTE: QUADRANTAL ANGLES

Quadrantal angles are angles whose terminal side lies on an axis, including 0°, 90°, 180°, 270°, or 360°.

HOW TO: GIVEN AN ANGLE MEASURE IN DEGREES, DRAW THE ANGLE IN STANDARD POSITION.

- Express the angle measure as a fraction of 360°.

- Reduce the fraction to simplest form.

- Draw an angle that contains that same fraction of the circle, beginning on the positive x-axis and moving counterclockwise for positive angles and clockwise for negative angles.

EXAMPLE 1: DRAWING AN ANGLE IN STANDARD POSITION MEASURED IN DEGREES

-

- Sketch an angle of 30° in standard position.

-

- Sketch an angle of −135° in standard position.

-

- Divide the angle measure by 360°.

[latex]\frac{-135^\circ }{360^\circ }=-\frac{3}{8}[/latex]

In this case, we can recognize that

[latex]-\frac{3}{8}=-\frac{3}{2}\left(\frac{1}{4}\right)[/latex]

- Divide the angle measure by 360°.

-

- Negative three-eighths is one and one-half times a quarter, so we place a line by moving clockwise one full quarter and one-half of another quarter, as in Figure 9.

Figure 17

- Negative three-eighths is one and one-half times a quarter, so we place a line by moving clockwise one full quarter and one-half of another quarter, as in Figure 9.

TRY IT 1

Show an angle of 240° on a circle in standard position.

Try It

Converting Between Degrees and Radians

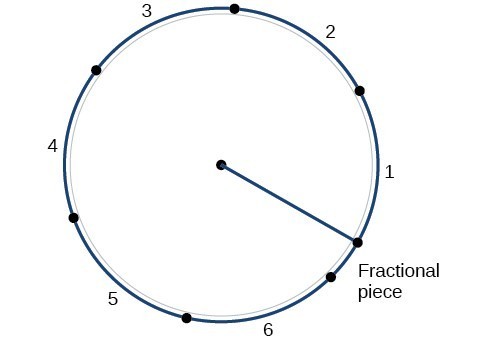

Dividing a circle into 360 parts is an arbitrary choice, although it creates the familiar degree measurement. We may choose other ways to divide a circle. To find another unit, think of the process of drawing a circle. Imagine that you stop before the circle is completed. The portion that you drew is referred to as an arc. An arc may be a portion of a full circle, a full circle, or more than a full circle, represented by more than one full rotation. The length of the arc around an entire circle is called the circumference of that circle.

The circumference of a circle is [latex]C=2\pi r[/latex]. If we divide both sides of this equation by [latex]r[/latex], we create the ratio of the circumference to the radius, which is always [latex]2\pi[/latex] regardless of the length of the radius. So the circumference of any circle is [latex]2\pi \approx 6.28[/latex] times the length of the radius. That means that if we took a string as long as the radius and used it to measure consecutive lengths around the circumference, there would be room for six full string-lengths and a little more than a quarter of a seventh, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 18

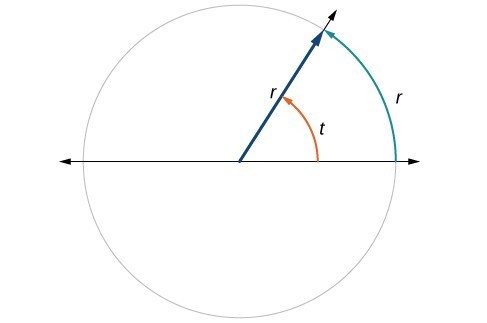

This brings us to our new angle measure. One radian is the measure of a central angle of a circle that intercepts an arc equal in length to the radius of that circle. A central angle is an angle formed at the center of a circle by two radii. Because the total circumference equals [latex]2\pi[/latex] times the radius, a full circular rotation is [latex]2\pi[/latex] radians. So

Note that when an angle is described without a specific unit, it refers to radian measure. For example, an angle measure of 3 indicates 3 radians. In fact, radian measure is dimensionless, since it is the quotient of a length (circumference) divided by a length (radius) and the length units cancel out.

Figure 19. The angle t sweeps out a measure of one radian. Note that the length of the intercepted arc is the same as the length of the radius of the circle.

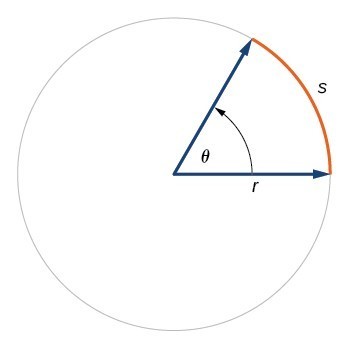

Relating Arc Lengths to Radius

An arc length [latex]s[/latex] is the length of the curve along the arc. Just as the full circumference of a circle always has a constant ratio to the radius, the arc length produced by any given angle also has a constant relation to the radius, regardless of the length of the radius.

This ratio, called the radian measure, is the same regardless of the radius of the circle—it depends only on the angle. This property allows us to define a measure of any angle as the ratio of the arc length [latex]s[/latex] to the radius [latex]r[/latex].

If [latex]s=r[/latex], then [latex]\theta =\frac{r}{r}=\text{ 1 radian}\text{.}[/latex]

Figure 20. (a) In an angle of 1 radian, the arc length [latex]s[/latex] equals the radius [latex]r[/latex]. (b) An angle of 2 radians has an arc length [latex]s=2r[/latex]. (c) A full revolution is [latex]2\pi[/latex] or about 6.28 radians.

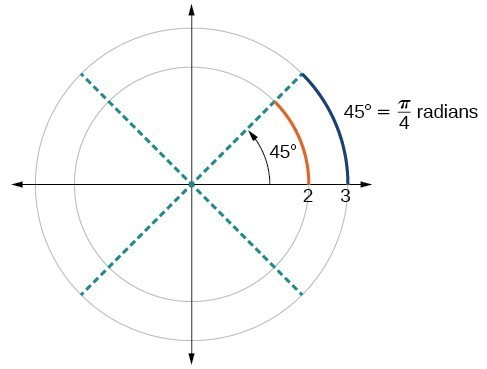

To elaborate on this idea, consider two circles, one with radius 2 and the other with radius 3. Recall the circumference of a circle is [latex]C=2\pi r[/latex], where [latex]r[/latex] is the radius. The smaller circle then has circumference [latex]2\pi \left(2\right)=4\pi[/latex] and the larger has circumference [latex]2\pi \left(3\right)=6\pi[/latex]. Now we draw a 45° angle on the two circles, as in Figure 13.

Figure 21. A 45° angle contains one-eighth of the circumference of a circle, regardless of the radius.

Figure 21. A 45° angle contains one-eighth of the circumference of a circle, regardless of the radius.

Notice what happens if we find the ratio of the arc length divided by the radius of the circle.

Since both ratios are [latex]\frac{1}{4}\pi[/latex], the angle measures of both circles are the same, even though the arc length and radius differ.

A GENERAL NOTE: RADIANS

One radian is the measure of the central angle of a circle such that the length of the arc between the initial side and the terminal side is equal to the radius of the circle. A full revolution (360°) equals [latex]2\pi[/latex] radians. A half revolution (180°) is equivalent to [latex]\pi[/latex] radians.

The radian measure of an angle is the ratio of the length of the arc subtended by the angle to the radius of the circle. In other words, if [latex]s[/latex] is the length of an arc of a circle, and [latex]r[/latex] is the radius of the circle, then the central angle containing that arc measures [latex]\frac{s}{r}[/latex] radians. In a circle of radius 1, the radian measure corresponds to the length of the arc.

Q & A

A MEASURE OF 1 RADIAN LOOKS TO BE ABOUT 60°. IS THAT CORRECT?

Yes. It is approximately 57.3°. Because [latex]2\pi[/latex] radians equals 360°, [latex]1[/latex] radian equals [latex]\frac{360^\circ }{2\pi }\approx 57.3^\circ[/latex].

Using Radians

Because radian measure is the ratio of two lengths, it is a unitless measure. For example, in Figure 12, suppose the radius were 2 inches and the distance along the arc were also 2 inches. When we calculate the radian measure of the angle, the “inches” cancel, and we have a result without units. Therefore, it is not necessary to write the label “radians” after a radian measure, and if we see an angle that is not labeled with “degrees” or the degree symbol, we can assume that it is a radian measure.

Considering the most basic case, the unit circle (a circle with radius 1), we know that 1 rotation equals 360 degrees, 360°. We can also track one rotation around a circle by finding the circumference, [latex]C=2\pi r[/latex], and for the unit circle [latex]C=2\pi[/latex]. These two different ways to rotate around a circle give us a way to convert from degrees to radians.

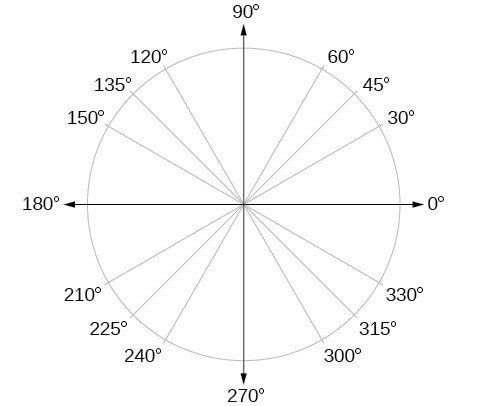

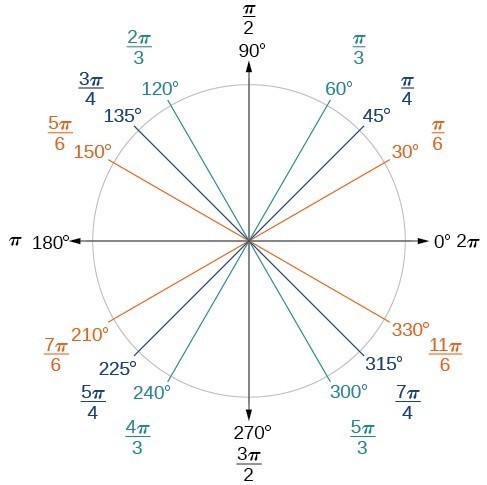

Identifying Special Angles Measured in Radians

In addition to knowing the measurements in degrees and radians of a quarter revolution, a half revolution, and a full revolution, there are other frequently encountered angles in one revolution of a circle with which we should be familiar. It is common to encounter multiples of 30, 45, 60, and 90 degrees. These values are shown in Figure 14. Memorizing these angles will be very useful as we study the properties associated with angles.

Figure 22. Commonly encountered angles measured in degrees

Now, we can list the corresponding radian values for the common measures of a circle corresponding to those listed in Figure 14, which are shown in Figure 15. Be sure you can verify each of these measures.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="487"] Figure 23. Commonly encountered angles measured in radians

Figure 23. Commonly encountered angles measured in radians

EXAMPLE 2: FINDING A RADIAN MEASURE

Find the radian measure of one-third of a full rotation.

TRY IT 3

Find the radian measure of three-fourths of a full rotation.

Converting between Radians and Degrees

Because degrees and radians both measure angles, we need to be able to convert between them. We can easily do so using a proportion.

This proportion shows that the measure of angle [latex]\theta[/latex] in degrees divided by 180 equals the measure of angle [latex]\theta[/latex] in radians divided by [latex]\pi .[/latex] Or, phrased another way, degrees is to 180 as radians is to [latex]\pi[/latex].

Converting between Radians and Degrees

To convert between degrees and radians, use the proportion

EXAMPLE 3: CONVERTING RADIANS TO DEGREES

Convert each radian measure to degrees.

a. [latex]\frac{\pi }{6}[/latex]

b. 3

TRY IT 4

Convert [latex]-\frac{3\pi }{4}[/latex] radians to degrees.

Try It

EXAMPLE 4: CONVERTING DEGREES TO RADIANS

Convert [latex]15[/latex] degrees to radians.

TRY IT 6

Convert 126° to radians.

Try It

Finding Coterminal Angles

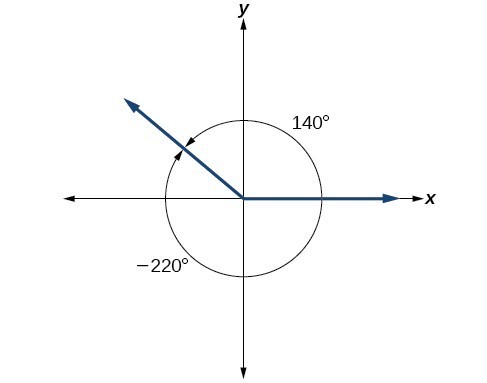

Converting between degrees and radians can make working with angles easier in some applications. For other applications, we may need another type of conversion. Negative angles and angles greater than a full revolution are more awkward to work with than those in the range of 0° to 360°, or 0 to [latex]2\pi[/latex]. It would be convenient to replace those out-of-range angles with a corresponding angle within the range of a single revolution.

It is possible for more than one angle to have the same terminal side. Look at Figure 16. The angle of 140° is a positive angle, measured counterclockwise. The angle of –220° is a negative angle, measured clockwise. But both angles have the same terminal side. If two angles in standard position have the same terminal side, they are coterminal angles. Every angle greater than 360° or less than 0° is coterminal with an angle between 0° and 360°, and it is often more convenient to find the coterminal angle within the range of 0° to 360° than to work with an angle that is outside that range.

Figure 24. An angle of 140° and an angle of –220° are coterminal angles.

This video shows examples of how to determine if two angles are coterminal.

Any angle has infinitely many coterminal angles because each time we add 360° to that angle—or subtract 360° from it—the resulting value has a terminal side in the same location. For example, 100° and 460° are coterminal for this reason, as is −260°. Recognizing that any angle has infinitely many coterminal angles explains the repetitive shape in the graphs of trigonometric functions.

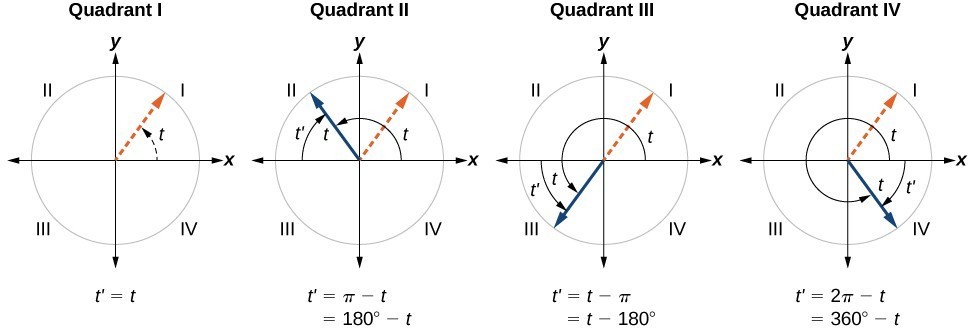

An angle’s reference angle is the measure of the smallest, positive, acute angle [latex]t[/latex] formed by the terminal side of the angle [latex]t[/latex] and the horizontal axis. Thus positive reference angles have terminal sides that lie in the first quadrant and can be used as models for angles in other quadrants. See Figure 17 for examples of reference angles for angles in different quadrants.

Figure 25

A GENERAL NOTE: COTERMINAL AND REFERENCE ANGLES

Coterminal angles are two angles in standard position that have the same terminal side.

An angle’s reference angle is the size of the smallest acute angle, [latex]{t}^{\prime }[/latex], formed by the terminal side of the angle [latex]t[/latex] and the horizontal axis.

HOW TO: GIVEN AN ANGLE GREATER THAN 360°, FIND A COTERMINAL ANGLE BETWEEN 0° AND 360°.

- Subtract 360° from the given angle.

- If the result is still greater than 360°, subtract 360° again till the result is between 0° and 360°.

- The resulting angle is coterminal with the original angle.

EXAMPLE 5: FINDING AN ANGLE COTERMINAL WITH AN ANGLE OF MEASURE GREATER THAN 360°

Find the least positive angle [latex]\theta[/latex] that is coterminal with an angle measuring 800°, where [latex]0^\circ \le \theta <360^\circ[/latex].

TRY IT 8

Find an angle [latex]\alpha[/latex] that is coterminal with an angle measuring 870°, where [latex]0^\circ \le \alpha <360^\circ[/latex].

HOW TO: GIVEN AN ANGLE WITH MEASURE LESS THAN 0°, FIND A COTERMINAL ANGLE HAVING A MEASURE BETWEEN 0° AND 360°.

- Add 360° to the given angle.

- If the result is still less than 0°, add 360° again until the result is between 0° and 360°.

- The resulting angle is coterminal with the original angle.

EXAMPLE 6: FINDING AN ANGLE COTERMINAL WITH AN ANGLE MEASURING LESS THAN 0°

Show the angle with measure −45° on a circle and find a positive coterminal angle [latex]\alpha[/latex] such that 0° ≤ α < 360°.

Watch this video for another example of how to determine positive and negative coterminal angles.

TRY IT 9

Find an angle [latex]\beta[/latex] that is coterminal with an angle measuring −300° such that [latex]0^\circ \le \beta <360^\circ[/latex].

Try It

Finding Coterminal Angles Measured in Radians

We can find coterminal angles measured in radians in much the same way as we have found them using degrees. In both cases, we find coterminal angles by adding or subtracting one or more full rotations.

Given an angle greater than [latex]2\pi[/latex], find a coterminal angle between 0 and [latex]2\pi[/latex].

- Subtract [latex]2\pi[/latex] from the given angle.

- If the result is still greater than [latex]2\pi[/latex], subtract [latex]2\pi[/latex] again until the result is between [latex]0[/latex] and [latex]2\pi[/latex].

- The resulting angle is coterminal with the original angle.

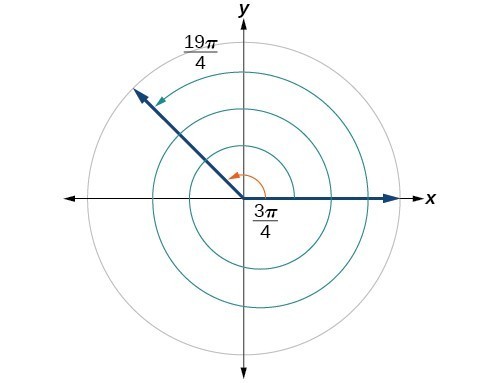

EXAMPLE 7: FINDING COTERMINAL ANGLES USING RADIANS

Find an angle [latex]\beta[/latex] that is coterminal with [latex]\frac{19\pi }{4}[/latex], where [latex]0\le \beta <2\pi[/latex].

TRY IT 11

Find an angle of measure [latex]\theta[/latex] that is coterminal with an angle of measure [latex]-\frac{17\pi }{6}[/latex] where [latex]0\le \theta <2\pi[/latex].

Try It

Determining the Length of an Arc

Recall that the radian measure [latex]\theta[/latex] of an angle was defined as the ratio of the arc length [latex]s[/latex] of a circular arc to the radius [latex]r[/latex] of the circle, [latex]\theta =\frac{s}{r}[/latex]. From this relationship, we can find arc length along a circle, given an angle.

A General Note: Arc Length on a Circle

In a circle of radius r, the length of an arc [latex]s[/latex] subtended by an angle with measure [latex]\theta[/latex] in radians, shown in Figure 20, is

[latex]s=r\theta[/latex]

Figure 29

How To: Given a circle of radius [latex]r[/latex], calculate the length [latex]s[/latex] of the arc subtended by a given angle of measure [latex]\theta[/latex].

- If necessary, convert [latex]\theta[/latex] to radians.

- Multiply the radius [latex]r[/latex] by the radian measure of [latex]\theta :s=r\theta[/latex].

Example 8: Finding the Length of an Arc

Assume the orbit of Mercury around the sun is a perfect circle. Mercury is approximately 36 million miles from the sun.

- In one Earth day, Mercury completes 0.0114 of its total revolution. How many miles does it travel in one day?

- Use your answer from part (a) to determine the radian measure for Mercury’s movement in one Earth day.

Try It

Find the arc length along a circle of radius 10 units subtended by an angle of 215°.

Try It

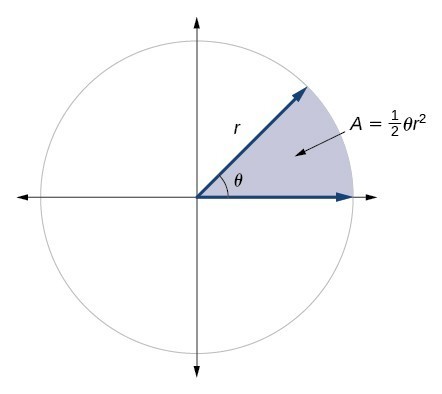

Finding the Area of a Sector of a Circle

A General Note: Area of a Sector

The area of a sector of a circle with radius [latex]r[/latex] subtended by an angle [latex]\theta[/latex], measured in radians, is

[latex]A=\frac{1}{2}\theta {r}^{2}[/latex]

Figure 30. The area of the sector equals half the square of the radius times the central angle measured in radians.

How To: Given a circle of radius [latex]r[/latex], find the area of a sector defined by a given angle [latex]\theta[/latex].

- If necessary, convert [latex]\theta[/latex] to radians.

- Multiply half the radian measure of [latex]\theta[/latex] by the square of the radius [latex]r:\text{ } A=\frac{1}{2}\theta {r}^{2}[/latex].

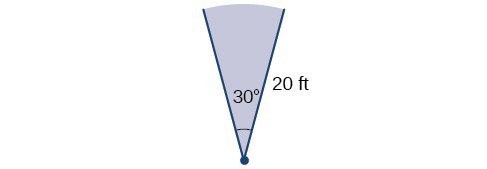

Example 9: Finding the Area of a Sector

An automatic lawn sprinkler sprays a distance of 20 feet while rotating 30 degrees, as shown in Figure 22. What is the area of the sector of grass the sprinkler waters?

Figure 31. The sprinkler sprays 20 ft within an arc of 30°.

Try It

In central pivot irrigation, a large irrigation pipe on wheels rotates around a center point. A farmer has a central pivot system with a radius of 400 meters. If water restrictions only allow her to water 150 thousand square meters a day, what angle should she set the system to cover? Write the answer in radian measure to two decimal places.

In the following video you will see how to calculate arc length and area of a sector of a circle.

Use Linear and Angular Speed to Describe Motion on a Circular Path

In addition to finding the area of a sector, we can use angles to describe the speed of a moving object. An object traveling in a circular path has two types of speed. Linear speed is speed along a straight path and can be determined by the distance it moves along (its displacement) in a given time interval. For instance, if a wheel with radius 5 inches rotates once a second, a point on the edge of the wheel moves a distance equal to the circumference, or [latex]10\pi[/latex] inches, every second. So the linear speed of the point is [latex]10\pi[/latex] in./s. The equation for linear speed is as follows where [latex]v[/latex] is linear speed, [latex]s[/latex] is displacement, and [latex]t[/latex]

is time.

Angular speed results from circular motion and can be determined by the angle through which a point rotates in a given time interval. In other words, angular speed is angular rotation per unit time. So, for instance, if a gear makes a full rotation every 4 seconds, we can calculate its angular speed as [latex]\frac{360\text{ degrees}}{4\text{ seconds}}=[/latex] 90 degrees per second. Angular speed can be given in radians per second, rotations per minute, or degrees per hour for example. The equation for angular speed is as follows, where [latex]\omega[/latex] (read as omega) is angular speed, [latex]\theta[/latex] is the angle traversed, and [latex]t[/latex] is time.

Combining the definition of angular speed with the arc length equation, [latex]s=r\theta[/latex], we can find a relationship between angular and linear speeds. The angular speed equation can be solved for [latex]\theta[/latex], giving [latex]\theta =\omega t[/latex]. Substituting this into the arc length equation gives:

Substituting this into the linear speed equation gives:

A General Note: Angular and Linear Speed

As a point moves along a circle of radius [latex]r[/latex], its angular speed, [latex]\omega[/latex], is the angular rotation [latex]\theta[/latex] per unit time, [latex]t[/latex].

[latex]\omega =\frac{\theta }{t}[/latex]

The linear speed. [latex]v[/latex], of the point can be found as the distance traveled, arc length [latex]s[/latex], per unit time, [latex]t[/latex].

[latex]v=\frac{s}{t}[/latex]

When the angular speed is measured in radians per unit time, linear speed and angular speed are related by the equation

[latex]v=r\omega[/latex]

This equation states that the angular speed in radians, [latex]\omega[/latex], representing the amount of rotation occurring in a unit of time, can be multiplied by the radius [latex]r[/latex] to calculate the total arc length traveled in a unit of time, which is the definition of linear speed.

How To: Given the amount of angle rotation and the time elapsed, calculate the angular speed.

- If necessary, convert the angle measure to radians.

- Divide the angle in radians by the number of time units elapsed: [latex]\omega =\frac{\theta }{t}[/latex].

- The resulting speed will be in radians per time unit.

Example 10: Finding Angular Speed

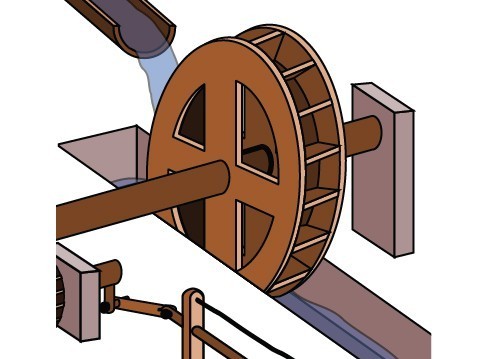

A water wheel, shown in Figure 23, completes 1 rotation every 5 seconds. Find the angular speed in radians per second.

Figure 32

Try It

An old vinyl record is played on a turntable rotating clockwise at a rate of 45 rotations per minute. Find the angular speed in radians per second.

Try It

How To: Given the radius of a circle, an angle of rotation, and a length of elapsed time, determine the linear speed.

- Convert the total rotation to radians if necessary.

- Divide the total rotation in radians by the elapsed time to find the angular speed: apply [latex]\omega =\frac{\theta }{t}[/latex].

- Multiply the angular speed by the length of the radius to find the linear speed, expressed in terms of the length unit used for the radius and the time unit used for the elapsed time: apply [latex]v=r\mathrm{\omega}[/latex].

Example 11: Finding a Linear Speed

A bicycle has wheels 28 inches in diameter. A tachometer determines the wheels are rotating at 180 RPM (revolutions per minute). Find the speed the bicycle is traveling down the road.

Try It

A satellite is rotating around Earth at 0.25 radians per hour at an altitude of 242 km above Earth. If the radius of Earth is 6378 kilometers, find the linear speed of the satellite in kilometers per hour.

Key Equations

| distance formula | [latex]d=\sqrt{(x_2-x_1)^2 + )y_2-y_1)^2}[/latex] |

| midpoint formula | [latex](\frac{x_1+x_2}{2}, \frac{y_1+y_2}{2}[/latex] |

| circle with radius [latex]r[/latex] and center at [latex](h,k)[/latex] | [latex](x-h)^2+(y-k)^2 = r^2[/latex] |

| arc length | [latex]s=r\theta[/latex] |

| area of a sector | [latex]A=\frac{1}{2}\theta {r}^{2}[/latex] |

| angular speed | [latex]\omega =\frac{\theta }{t}[/latex] |

| linear speed | [latex]v=\frac{s}{t}[/latex] |

| linear speed related to angular speed | [latex]v=r\omega[/latex] |

Key Concepts

- The Pythagorean Theorem says that for all right triangles with legs of length [latex]a[/latex] and [latex]b[/latex] and hypotenuse of length [latex]c[/latex], we have [latex]a^2+b^2 = c^2[/latex].

- The distance formula can be used to find the distance between two points on the coordinate plane.

- The midpoint formula can be used to find the point halfway between two given points on the coordinate plane.

- A circle is not a function because it does not pass the vertical line test.

- An angle is formed from the union of two rays, by keeping the initial side fixed and rotating the terminal side. The amount of rotation determines the measure of the angle.

- An angle is in standard position if its vertex is at the origin and its initial side lies along the positive x-axis. A positive angle is measured counterclockwise from the initial side and a negative angle is measured clockwise.

- To draw an angle in standard position, draw the initial side along the positive x-axis and then place the terminal side according to the fraction of a full rotation the angle represents.

- In addition to degrees, the measure of an angle can be described in radians.

- To convert between degrees and radians, use the proportion [latex]\frac{\theta }{180}=\frac{{\theta }^{R}}{\pi }[/latex].

- Two angles that have the same terminal side are called coterminal angles.

- We can find coterminal angles by adding or subtracting 360° or [latex]2\pi[/latex].

- Coterminal angles can be found using radians just as they are for degrees.

- The length of a circular arc is a fraction of the circumference of the entire circle.

- The area of sector is a fraction of the area of the entire circle.

- An object moving in a circular path has both linear and angular speed.

- The angular speed of an object traveling in a circular path is the measure of the angle through which it turns in a unit of time.

- The linear speed of an object traveling along a circular path is the distance it travels in a unit of time.

Glossary

- angle

- the union of two rays having a common endpoint

- angular speed

- the angle through which a rotating object travels in a unit of time

- arc length

- the length of the curve formed by an arc

- area of a sector

- area of a portion of a circle bordered by two radii and the intercepted arc; the fraction [latex]\frac{\theta }{2\pi }[/latex] multiplied by the area of the entire circle

- circle

- the geometric set of all points that are a fixed distance from a given point.

- coterminal angles

- description of positive and negative angles in standard position sharing the same terminal side

- degree

- a unit of measure describing the size of an angle as one-360th of a full revolution of a circle

- initial side

- the side of an angle from which rotation begins

- linear speed

- the distance along a straight path a rotating object travels in a unit of time; determined by the arc length

- measure of an angle

- the amount of rotation from the initial side to the terminal side

- negative angle

- description of an angle measured clockwise from the positive x-axis

- positive angle

- description of an angle measured counterclockwise from the positive x-axis

- quadrantal angle

- an angle whose terminal side lies on an axis

- radian measure

- the ratio of the arc length formed by an angle divided by the radius of the circle

- radian

- the measure of a central angle of a circle that intercepts an arc equal in length to the radius of that circle

- ray

- one point on a line and all points extending in one direction from that point; one side of an angle

- reference angle

- the measure of the acute angle formed by the terminal side of the angle and the horizontal axis

- standard position

- the position of an angle having the vertex at the origin and the initial side along the positive x-axis

- terminal side

- the side of an angle at which rotation ends

- vertex

- the common endpoint of two rays that form an angle

Candela Citations

- Angles. Authored by: OpenStax College. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/fd53eae1-fa23-47c7-bb1b-972349835c3c@5.175:1/Preface. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Animation: Angles in Standard Position. Authored by: Mathispower4u. Located at: https://youtu.be/hpIjaKLOo6o. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Examples: Determine Angles of Rotation. Authored by: Mathispower4u. Located at: https://youtu.be/0yHDfG2m-44.. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Radian Measure. Authored by: Mathispower4u. Located at: https://youtu.be/nAJqXtzwpXQ.. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Example: Determine if Two Angles Are Coterminal. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TuyF8fFg3B0. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Example: Determine Positive and Negative Coterminal Angles. Authored by: Mathispower4u. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m7jTGVVzb0s. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Arc Length and Area of a Sector. Authored by: Mathispower4u. Located at: https://youtu.be/zD4CsKIYEHo. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Example: Determine Angular and Linear Velocity. Authored by: Mathispower4u. Located at: https://youtu.be/bfWkgA5GSE0. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License