Learning Outcomes

- Find function values for the sine and cosine of the special angles.

- Identify the domain and range of sine and cosine functions.

- Use reference angles to evaluate trigonometric functions.

- Evaluate sine and cosine values using a calculator.

- Find exact values of the trigonometric functions secant, cosecant, tangent, and cotangent of 30° (π/6), 45° (π/4), and 60° (π/3).

- Use reference angles to evaluate the trigonometric functions secant, cosecant, tangent, and cotangent.

- Use properties of even and odd trigonometric functions.

- Recognize and use fundamental identities.

- Evaluate trigonometric functions with a calculator.

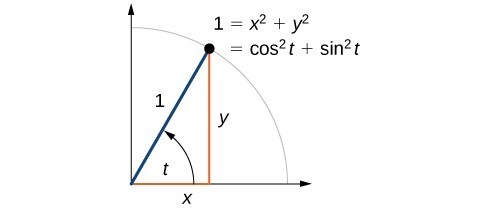

To define our trigonometric functions, we begin by drawing a unit circle, a circle centered at the origin with radius 1, as shown in Figure 2. The angle (in radians) that [latex]t[/latex] intercepts forms an arc of length [latex]s[/latex]. Using the formula [latex]s=rt[/latex], and knowing that [latex]r=1[/latex], we see that for a unit circle, [latex]s=t[/latex].

Recall that the x- and y-axes divide the coordinate plane into four quarters called quadrants. We label these quadrants to mimic the direction a positive angle would sweep. The four quadrants are labeled I, II, III, and IV.

For any angle [latex]t[/latex], we can label the intersection of the terminal side and the unit circle as by its coordinates, [latex]\left(x,y\right)[/latex]. The coordinates [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex] will be the outputs of the trigonometric functions [latex]f\left(t\right)=\cos t[/latex] and [latex]f\left(t\right)=\sin t[/latex], respectively. This means [latex]x=\cos t[/latex] and [latex]y=\sin t[/latex].

Figure 2. Unit circle where the central angle is [latex]t[/latex] radians

A General Note: Unit Circle

A unit circle has a center at [latex]\left(0,0\right)[/latex] and radius [latex]1[/latex] . In a unit circle, the length of the intercepted arc is equal to the radian measure of the central angle [latex]1[/latex].

Let [latex]\left(x,y\right)[/latex] be the endpoint on the unit circle of an arc of arc length [latex]s[/latex]. The [latex]\left(x,y\right)[/latex] coordinates of this point can be described as functions of the angle.

Defining Sine and Cosine Functions

Now that we have our unit circle labeled, we can learn how the [latex]\left(x,y\right)[/latex] coordinates relate to the arc length and angle. The sine function relates a real number [latex]t[/latex] to the y-coordinate of the point where the corresponding angle intercepts the unit circle. More precisely, the sine of an angle [latex]t[/latex] equals the y-value of the endpoint on the unit circle of an arc of length [latex]t[/latex]. In Figure 2, the sine is equal to [latex]y[/latex]. Like all functions, the sine function has an input and an output. Its input is the measure of the angle; its output is the y-coordinate of the corresponding point on the unit circle.

The cosine function of an angle [latex]t[/latex] equals the x-value of the endpoint on the unit circle of an arc of length [latex]t[/latex]. In Figure 3, the cosine is equal to [latex]x[/latex].

Figure 3

Because it is understood that sine and cosine are functions, we do not always need to write them with parentheses: [latex]\sin t[/latex] is the same as [latex]\sin \left(t\right)[/latex] and [latex]\cos t[/latex] is the same as [latex]\cos \left(t\right)[/latex]. Likewise, [latex]{\cos }^{2}t[/latex] is a commonly used shorthand notation for [latex]{\left(\cos \left(t\right)\right)}^{2}[/latex]. Be aware that many calculators and computers do not recognize the shorthand notation. When in doubt, use the extra parentheses when entering calculations into a calculator or computer.

A General Note: Sine and Cosine Functions

If [latex]t[/latex] is a real number and a point [latex]\left(x,y\right)[/latex] on the unit circle corresponds to an angle of [latex]t[/latex], then

How To: Given a point P [latex]\left(x,y\right)[/latex] on the unit circle corresponding to an angle of [latex]t[/latex], find the sine and cosine.

- The sine of [latex]t[/latex] is equal to the y-coordinate of point [latex]P:\sin t=y[/latex].

- The cosine of [latex]t[/latex] is equal to the x-coordinate of point [latex]P: \text{cos}t=x[/latex].

Example 1: Finding Function Values for Sine and Cosine

Point [latex]P[/latex] is a point on the unit circle corresponding to an angle of [latex]t[/latex], as shown in Figure 4. Find [latex]\cos \left(t\right)[/latex] and [latex]\text{sin}\left(t\right)[/latex].

Figure 4

Try It

A certain angle [latex]t[/latex] corresponds to a point on the unit circle at [latex]\left(-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2},\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\right)[/latex] as shown in Figure 5. Find [latex]\cos t[/latex] and [latex]\sin t[/latex].

Figure 5

Finding Sines and Cosines of Angles on an Axis

For quadrantral angles, the corresponding point on the unit circle falls on the x- or y-axis. In that case, we can easily calculate cosine and sine from the values of [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex].

Example 2: Calculating Sines and Cosines along an Axis

Find [latex]\cos \left(90^\circ \right)[/latex] and [latex]\text{sin}\left(90^\circ \right)[/latex].

Try It

Find cosine and sine of the angle [latex]\pi[/latex].

The Pythagorean Identity

Figure 7

Now that we can define sine and cosine, we will learn how they relate to each other and the unit circle. Recall that the equation for the unit circle is [latex]{x}^{2}+{y}^{2}=1[/latex]. Because [latex]x=\cos t[/latex] and [latex]y=\sin t[/latex], we can substitute for [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex] to get [latex]{\cos }^{2}t+{\sin }^{2}t=1[/latex]. This equation, [latex]{\cos }^{2}t+{\sin }^{2}t=1[/latex], is known as the Pythagorean Identity.

We can use the Pythagorean Identity to find the cosine of an angle if we know the sine, or vice versa. However, because the equation yields two solutions, we need additional knowledge of the angle to choose the solution with the correct sign. If we know the quadrant where the angle is, we can easily choose the correct solution.

A General Note: Pythagorean Identity

The Pythagorean Identity states that, for any real number [latex]t[/latex],

How To: Given the sine of some angle [latex]t[/latex] and its quadrant location, find the cosine of [latex]t[/latex].

- Substitute the known value of [latex]\sin \left(t\right)[/latex] into the Pythagorean Identity.

- Solve for [latex]\cos \left(t\right)[/latex].

- Choose the solution with the appropriate sign for the x-values in the quadrant where [latex]t[/latex] is located.

Example 3: Finding a Cosine from a Sine or a Sine from a Cosine

If [latex]\sin \left(t\right)=\frac{3}{7}[/latex] and [latex]t[/latex] is in the second quadrant, find [latex]\cos \left(t\right)[/latex].

Try It

If [latex]\cos \left(t\right)=\frac{24}{25}[/latex] and [latex]t[/latex] is in the fourth quadrant, find [latex]\sin\left(t\right)[/latex].

Try It

Finding Sines and Cosines of Special Angles

We have already learned some properties of the special angles, such as the conversion from radians to degrees. We can also calculate sines and cosines of the special angles using the Pythagorean Identity and our knowledge of triangles.

Finding Sines and Cosines of 45° Angles

First, we will look at angles of [latex]45^\circ[/latex] or [latex]\frac{\pi }{4}[/latex], as shown in Figure 9. A [latex]45^\circ -45^\circ -90^\circ[/latex] triangle is an isosceles triangle, so the x- and y-coordinates of the corresponding point on the circle are the same. Because the x- and y-values are the same, the sine and cosine values will also be equal.

Figure 9

At [latex]t=\frac{\pi }{4}[/latex] , which is 45 degrees, the radius of the unit circle bisects the first quadrantal angle. This means the radius lies along the line [latex]y=x[/latex]. A unit circle has a radius equal to 1. So, the right triangle formed below the line [latex]y=x[/latex] has sides [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y\text{ }\left(y=x\right)[/latex], and a radius = 1.

Figure 10

From the Pythagorean Theorem we get

Substituting [latex]y=x[/latex], we get

Combining like terms we get

And solving for [latex]x[/latex], we get

In quadrant I, [latex]x=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}[/latex].

At [latex]t=\frac{\pi }{4}[/latex] or 45 degrees,

If we then rationalize the denominators, we get

Therefore, the [latex]\left(x,y\right)[/latex] coordinates of a point on a circle of radius [latex]1[/latex] at an angle of [latex]45^\circ[/latex] are [latex]\left(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2},\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\right)[/latex].

Finding Sines and Cosines of 30° and 60° Angles

Next, we will find the cosine and sine at an angle of [latex]30^\circ[/latex], or [latex]\frac{\pi }{6}[/latex] . First, we will draw a triangle inside a circle with one side at an angle of [latex]30^\circ[/latex], and another at an angle of [latex]-30^\circ[/latex], as shown in Figure 11. If the resulting two right triangles are combined into one large triangle, notice that all three angles of this larger triangle will be [latex]60^\circ[/latex], as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 11

Figure 12

Because all the angles are equal, the sides are also equal. The vertical line has length [latex]2y[/latex], and since the sides are all equal, we can also conclude that [latex]r=2y[/latex] or [latex]y=\frac{1}{2}r[/latex]. Since [latex]\sin t=y[/latex] ,

And since [latex]r=1[/latex] in our unit circle,

Using the Pythagorean Identity, we can find the cosine value.

The [latex]\left(x,y\right)[/latex] coordinates for the point on a circle of radius [latex]1[/latex] at an angle of [latex]30^\circ[/latex] are [latex]\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2},\frac{1}{2}\right)[/latex]. At [latex]t=\frac{\pi }{3}[/latex] (60°), the radius of the unit circle, 1, serves as the hypotenuse of a 30-60-90 degree right triangle, [latex]BAD[/latex], as shown in Figure 13 below. Angle [latex]A[/latex] has measure [latex]60^\circ[/latex]. At point [latex]B[/latex], we draw an angle [latex]ABC[/latex] with measure of [latex]60^\circ[/latex]. We know the angles in a triangle sum to [latex]180^\circ[/latex], so the measure of angle [latex]C[/latex] is also [latex]60^\circ[/latex]. Now we have an equilateral triangle. Because each side of the equilateral triangle [latex]ABC[/latex] is the same length, and we know one side is the radius of the unit circle, all sides must be of length 1.

Figure 13

The measure of angle [latex]ABD[/latex] is 30°. So, if double, angle [latex]ABC[/latex] is 60°. [latex]BD[/latex] is the perpendicular bisector of [latex]AC[/latex], so it cuts [latex]AC[/latex] in half. This means that [latex]AD[/latex] is [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex] the radius, or [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex]. Notice that [latex]AD[/latex] is the x-coordinate of point [latex]B[/latex], which is at the intersection of the 60° angle and the unit circle. This gives us a triangle [latex]BAD[/latex] with hypotenuse of 1 and side [latex]x[/latex] of length [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex].

From the Pythagorean Theorem, we get

Substituting [latex]x=\frac{1}{2}[/latex], we get

Solving for [latex]y[/latex], we get

Since [latex]t=\frac{\pi }{3}[/latex] has the terminal side in quadrant I where the y-coordinate is positive, we choose [latex]y=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\[/latex], the positive value.

At [latex]t=\frac{\pi }{3}[/latex] (60°), the [latex]\left(x,y\right)[/latex] coordinates for the point on a circle of radius [latex]1[/latex] at an angle of [latex]60^\circ[/latex] are [latex]\left(\frac{1}{2},\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)\[/latex], so we can find the sine and cosine.

We have now found the cosine and sine values for all of the most commonly encountered angles in the first quadrant of the unit circle. The table below summarizes these values.

| Angle | 0 | [latex]\frac{\pi }{6}[/latex], or 30° | [latex]\frac{\pi }{4}[/latex], or 45° | [latex]\frac{\pi }{3}[/latex], or 60° | [latex]\frac{\pi }{2}[/latex], or 90° |

| Cosine | 1 | [latex]\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}[/latex] | [latex]\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}[/latex] | [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex] | 0 |

| Sine | 0 | [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex] | [latex]\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}[/latex] | [latex]\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}[/latex] | 1 |

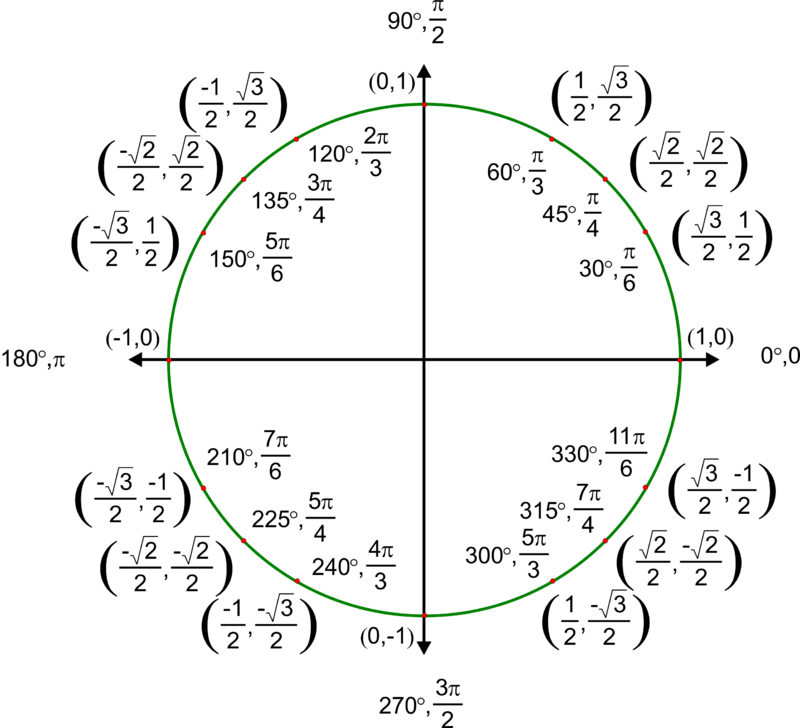

Figure 14 shows the common angles in the first quadrant of the unit circle.

Figure 14

Using a Calculator to Find Sine and Cosine

To find the cosine and sine of angles other than the special angles, we turn to a computer or calculator. Be aware: Most calculators can be set into “degree” or “radian” mode, which tells the calculator the units for the input value. When we evaluate [latex]\cos \left(30\right)[/latex] on our calculator, it will evaluate it as the cosine of 30 degrees if the calculator is in degree mode, or the cosine of 30 radians if the calculator is in radian mode.

How To: Given an angle in radians, use a graphing calculator to find the cosine.

- If the calculator has degree mode and radian mode, set it to radian mode.

- Press the COS key.

- Enter the radian value of the angle and press the close-parentheses key “)”.

- Press ENTER.

Example 4: Using a Graphing Calculator to Find Sine and Cosine

Evaluate [latex]\cos \left(\frac{5\pi }{3}\right)[/latex] using a graphing calculator or computer.

Try It

Evaluate [latex]\sin \left(\frac{\pi }{3}\right)[/latex].

Identifying the Domain and Range of Sine and Cosine Functions

Now that we can find the sine and cosine of an angle, we need to discuss their domains and ranges. What are the domains of the sine and cosine functions? That is, what are the smallest and largest numbers that can be inputs of the functions? Because angles smaller than 0 and angles larger than [latex]2\pi[/latex] can still be graphed on the unit circle and have real values of [latex]x,y[/latex], and [latex]r[/latex], there is no lower or upper limit to the angles that can be inputs to the sine and cosine functions. The input to the sine and cosine functions is the rotation from the positive x-axis, and that may be any real number.

What are the ranges of the sine and cosine functions? What are the least and greatest possible values for their output? We can see the answers by examining the unit circle, as shown in Figure 15. The bounds of the x-coordinate are [latex]\left[-1,1\right][/latex]. The bounds of the y-coordinate are also [latex]\left[-1,1\right][/latex]. Therefore, the range of both the sine and cosine functions is [latex]\left[-1,1\right][/latex].

Figure 15

We have discussed finding the sine and cosine for angles in the first quadrant, but what if our angle is in another quadrant? For any given angle in the first quadrant, there is an angle in the second quadrant with the same sine value. Because the sine value is the y-coordinate on the unit circle, the other angle with the same sine will share the same y-value, but have the opposite x-value. Therefore, its cosine value will be the opposite of the first angle’s cosine value.

Likewise, there will be an angle in the fourth quadrant with the same cosine as the original angle. The angle with the same cosine will share the same x-value but will have the opposite y-value. Therefore, its sine value will be the opposite of the original angle’s sine value.

As shown in Figure 16, angle [latex]\alpha[/latex] has the same sine value as angle [latex]t[/latex]; the cosine values are opposites. Angle [latex]\beta[/latex] has the same cosine value as angle [latex]t[/latex]; the sine values are opposites.

[latex]\begin{array}{ccc}\sin \left(t\right)=\sin \left(\alpha \right)\hfill & \text{and}\hfill & \cos \left(t\right)=-\cos \left(\alpha \right)\hfill \\ \sin \left(t\right)=-\sin \left(\beta \right)\hfill & \text{and}\hfill & \cos \left(t\right)=\cos \left(\beta \right)\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

Figure 16

Recall that an angle’s reference angle is the acute angle, [latex]t[/latex], formed by the terminal side of the angle [latex]t[/latex] and the horizontal axis. A reference angle is always an angle between [latex]0[/latex] and [latex]90^\circ[/latex], or [latex]0[/latex] and [latex]\frac{\pi }{2}[/latex] radians. As we can see from Figure 17, for any angle in quadrants II, III, or IV, there is a reference angle in quadrant I.

Figure 17

How To: Given an angle between [latex]0[/latex] and [latex]2\pi[/latex], find its reference angle.

- An angle in the first quadrant is its own reference angle.

- For an angle in the second or third quadrant, the reference angle is [latex]|\pi -t|[/latex] or [latex]|180^\circ \mathrm{-t}|[/latex].

- For an angle in the fourth quadrant, the reference angle is [latex]2\pi -t[/latex] or [latex]360^\circ \mathrm{-t}[/latex].

- If an angle is less than [latex]0[/latex] or greater than [latex]2\pi[/latex], add or subtract [latex]2\pi[/latex] as many times as needed to find an equivalent angle between [latex]0[/latex] and [latex]2\pi[/latex].

Example 5: Finding a Reference Angle

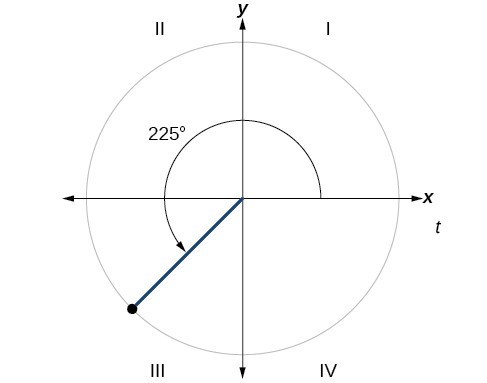

Find the reference angle of [latex]225^\circ[/latex] as shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18

Try It

Find the reference angle of [latex]\frac{5\pi }{3}[/latex].

Using Reference Angles

Now let’s take a moment to reconsider the Ferris wheel introduced at the beginning of this section. Suppose a rider snaps a photograph while stopped twenty feet above ground level. The rider then rotates three-quarters of the way around the circle. What is the rider’s new elevation? To answer questions such as this one, we need to evaluate the sine or cosine functions at angles that are greater than 90 degrees or at a negative angle. Reference angles make it possible to evaluate trigonometric functions for angles outside the first quadrant. They can also be used to find [latex]\left(x,y\right)[/latex] coordinates for those angles. We will use the reference angle of the angle of rotation combined with the quadrant in which the terminal side of the angle lies.

Using Reference Angles to Evaluate Trigonometric Functions

We can find the cosine and sine of any angle in any quadrant if we know the cosine or sine of its reference angle. The absolute values of the cosine and sine of an angle are the same as those of the reference angle. The sign depends on the quadrant of the original angle. The cosine will be positive or negative depending on the sign of the x-values in that quadrant. The sine will be positive or negative depending on the sign of the y-values in that quadrant.

A General Note: Using Reference Angles to Find Cosine and Sine

Angles have cosines and sines with the same absolute value as their reference angles. The sign (positive or negative) can be determined from the quadrant of the angle.

How To: Given an angle in standard position, find the reference angle, and the cosine and sine of the original angle.

- Measure the angle between the terminal side of the given angle and the horizontal axis. This is the reference angle.

- Determine the values of the cosine and sine of the reference angle.

- Give the cosine the same sign as the x-values in the quadrant of the original angle.

- Give the sine the same sign as the y-values in the quadrant of the original angle.

Example 6: Using Reference Angles to Find Sine and Cosine

- Using a reference angle, find the exact value of [latex]\cos \left(150^\circ \right)[/latex] and [latex]\text{sin}\left(150^\circ \right)[/latex].

- Using the reference angle, find [latex]\cos \frac{5\pi }{4}[/latex] and [latex]\sin \frac{5\pi }{4}[/latex].

Try It

a. Use the reference angle of [latex]315^\circ[/latex] to find [latex]\cos \left(315^\circ \right)[/latex] and [latex]\sin \left(315^\circ \right)[/latex].

b. Use the reference angle of [latex]-\frac{\pi }{6}[/latex] to find [latex]\cos \left(-\frac{\pi }{6}\right)[/latex] and [latex]\sin \left(-\frac{\pi }{6}\right)[/latex].

Try It

Using Reference Angles to Find Coordinates

Now that we have learned how to find the cosine and sine values for special angles in the first quadrant, we can use symmetry and reference angles to fill in cosine and sine values for the rest of the special angles on the unit circle. They are shown in Figure 19. Take time to learn the [latex]\left(x,y\right)[/latex] coordinates of all of the major angles in the first quadrant.

In addition to learning the values for special angles, we can use reference angles to find [latex]\left(x,y\right)[/latex] coordinates of any point on the unit circle, using what we know of reference angles along with the identities

First we find the reference angle corresponding to the given angle. Then we take the sine and cosine values of the reference angle, and give them the signs corresponding to the y– and x-values of the quadrant.

How To: Given the angle of a point on a circle and the radius of the circle, find the [latex]\left(x,y\right)[/latex] coordinates of the point.

- Find the reference angle by measuring the smallest angle to the x-axis.

- Find the cosine and sine of the reference angle.

- Determine the appropriate signs for [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex]

in the given quadrant.

Example 7: Using the Unit Circle to Find Coordinates

Find the coordinates of the point on the unit circle at an angle of [latex]\frac{7\pi }{6}[/latex].

Try It

Find the coordinates of the point on the unit circle at an angle of [latex]\frac{5\pi }{3}[/latex].

Find exact values of the trigonometric functions secant, cosecant, tangent, and cotangent

To define the remaining functions, we will once again draw a unit circle with a point [latex]\left(x,y\right)[/latex] corresponding to an angle of [latex]t[/latex], as shown in Figure 1. As with the sine and cosine, we can use the [latex]\left(x,y\right)[/latex] coordinates to find the other functions.

Figure 19

The first function we will define is the tangent. The tangent of an angle is the ratio of the y-value to the x-value of the corresponding point on the unit circle. In Figure 1, the tangent of angle [latex]t[/latex] is equal to [latex]\frac{y}{x},x\ne 0[/latex]. Because the y-value is equal to the sine of [latex]t[/latex], and the x-value is equal to the cosine of [latex]t[/latex], the tangent of angle [latex]t[/latex] can also be defined as [latex]\frac{\sin t}{\cos t},\cos t\ne 0[/latex]. The tangent function is abbreviated as [latex]\tan[/latex]. The remaining three functions can all be expressed as reciprocals of functions we have already defined.

- The secant function is the reciprocal of the cosine function. In Figure 1, the secant of angle [latex]t[/latex] is equal to [latex]\frac{1}{\cos t}=\frac{1}{x},x\ne 0[/latex]. The secant function is abbreviated as [latex]\sec[/latex].

- The cotangent function is the reciprocal of the tangent function. In Figure 1, the cotangent of angle [latex]t[/latex] is equal to [latex]\frac{\cos t}{\sin t}=\frac{x}{y},y\ne 0[/latex]. The cotangent function is abbreviated as [latex]\cot[/latex].

- The cosecant function is the reciprocal of the sine function. In Figure 1, the cosecant of angle [latex]t[/latex] is equal to [latex]\frac{1}{\sin t}=\frac{1}{y},y\ne 0[/latex]. The cosecant function is abbreviated as [latex]\csc[/latex].

A General Note: Tangent, Secant, Cosecant, and Cotangent Functions

If [latex]t[/latex] is a real number and [latex]\left(x,y\right)[/latex] is a point where the terminal side of an angle of [latex]t[/latex] radians intercepts the unit circle, then

[latex]\begin{gathered}\tan t=\frac{y}{x},x\ne 0\\ \sec t=\frac{1}{x},x\ne 0\\ \csc t=\frac{1}{y},y\ne 0\\ \cot t=\frac{x}{y},y\ne 0\end{gathered}[/latex]

Example 8: Finding Trigonometric Functions from a Point on the Unit Circle

The point [latex]\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2},\frac{1}{2}\right)[/latex] is on the unit circle, as shown in Figure 2. Find [latex]\sin t,\cos t,\tan t,\sec t,\csc t[/latex], and [latex]\cot t[/latex].

Figure 20

Try It

The point [latex]\left(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2},-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\right)[/latex] is on the unit circle, as shown in Figure 3. Find [latex]\sin t,\cos t,\tan t,\sec t,\csc t[/latex], and [latex]\cot t[/latex].

Figure 21

Example 9: Finding the Trigonometric Functions of an Angle

Find [latex]\sin t,\cos t,\tan t,\sec t,\csc t[/latex], and [latex]\cot t[/latex] when [latex]t=\frac{\pi }{6}[/latex].

Try It

Find [latex]\sin t,\cos t,\tan t,\sec t,\csc t[/latex], and [latex]\cot t[/latex] when [latex]t=\frac{\pi }{3}[/latex].

Try It

Because we know the sine and cosine values for the common first-quadrant angles, we can find the other function values for those angles as well by setting [latex]x[/latex] equal to the cosine and [latex]y[/latex] equal to the sine and then using the definitions of tangent, secant, cosecant, and cotangent. The results are shown in the table below.

| Angle | [latex]0[/latex] | [latex]\frac{\pi }{6},\text{ or }{30}^{\circ}[/latex] | [latex]\frac{\pi }{4},\text{ or } {45}^{\circ }[/latex] | [latex]\frac{\pi }{3},\text{ or }{60}^{\circ }[/latex] | [latex]\frac{\pi }{2},\text{ or }{90}^{\circ }[/latex] |

| Cosine | 1 | [latex]\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}[/latex] | [latex]\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}[/latex] | [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex] | 0 |

| Sine | 0 | [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex] | [latex]\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}[/latex] | [latex]\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}[/latex] | 1 |

| Tangent | 0 | [latex]\frac{\sqrt{3}}{3}[/latex] | 1 | [latex]\sqrt{3}[/latex] | Undefined |

| Secant | 1 | [latex]\frac{2\sqrt{3}}{3}[/latex] | [latex]\sqrt{2}[/latex] | 2 | Undefined |

| Cosecant | Undefined | 2 | [latex]\sqrt{2}[/latex] | [latex]\frac{2\sqrt{3}}{3}[/latex] | 1 |

| Cotangent | Undefined | [latex]\sqrt{3}[/latex] | 1 | [latex]\frac{\sqrt{3}}{3}[/latex] | 0 |

Using Reference Angles to Evaluate Tangent, Secant, Cosecant, and Cotangent

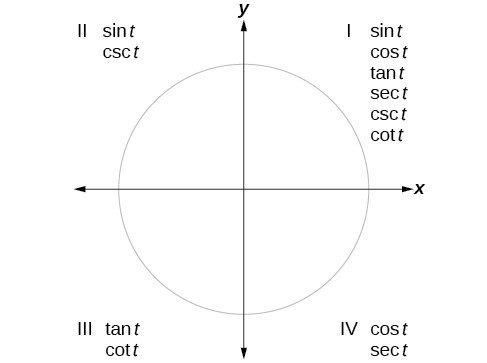

We can evaluate trigonometric functions of angles outside the first quadrant using reference angles as we have already done with the sine and cosine functions. The procedure is the same: Find the reference angle formed by the terminal side of the given angle with the horizontal axis. The trigonometric function values for the original angle will be the same as those for the reference angle, except for the positive or negative sign, which is determined by x– and y-values in the original quadrant. Figure 4 shows which functions are positive in which quadrant.

To help us remember which of the six trigonometric functions are positive in each quadrant, we can use the mnemonic phrase “A Smart Trig Class.” Each of the four words in the phrase corresponds to one of the four quadrants, starting with quadrant I and rotating counterclockwise. In quadrant I, which is “A,” all of the six trigonometric functions are positive. In quadrant II, “Smart,” only sine and its reciprocal function, cosecant, are positive. In quadrant III, “Trig,” only tangent and its reciprocal function, cotangent, are positive. Finally, in quadrant IV, “Class,” only cosine and its reciprocal function, secant, are positive.

Figure 22

How To: Given an angle not in the first quadrant, use reference angles to find all six trigonometric functions.

- Measure the angle formed by the terminal side of the given angle and the horizontal axis. This is the reference angle.

- Evaluate the function at the reference angle.

- Observe the quadrant where the terminal side of the original angle is located. Based on the quadrant, determine whether the output is positive or negative.

Example 10: Using Reference Angles to Find Trigonometric Functions

Use reference angles to find all six trigonometric functions of [latex]-\frac{5\pi }{6}[/latex].

Try It

Use reference angles to find all six trigonometric functions of [latex]-\frac{7\pi }{4}[/latex].

Try It

Using Even and Odd Trigonometric Functions

To be able to use our six trigonometric functions freely with both positive and negative angle inputs, we should examine how each function treats a negative input. As it turns out, there is an important difference among the functions in this regard.

Consider the function [latex]f\left(x\right)={x}^{2}[/latex], shown in Figure 5. The graph of the function is symmetrical about the y-axis. All along the curve, any two points with opposite x-values have the same function value. This matches the result of calculation: [latex]{\left(4\right)}^{2}={\left(-4\right)}^{2}[/latex], [latex]{\left(-5\right)}^{2}={\left(5\right)}^{2}[/latex], and so on. So [latex]f\left(x\right)={x}^{2}[/latex] is an even function, a function such that two inputs that are opposites have the same output. That means [latex]f\left(-x\right)=f\left(x\right)[/latex].

Figure 23. The function [latex]f\left(x\right)={x}^{2}[/latex] is an even function.

Now consider the function [latex]f\left(x\right)={x}^{3}[/latex], shown in Figure 6. The graph is not symmetrical about the y-axis. All along the graph, any two points with opposite x-values also have opposite y-values. So [latex]f\left(x\right)={x}^{3}[/latex] is an odd function, one such that two inputs that are opposites have outputs that are also opposites. That means [latex]f\left(-x\right)=-f\left(x\right)[/latex].

Figure 24. The function [latex]f\left(x\right)={x}^{3}[/latex] is an odd function.

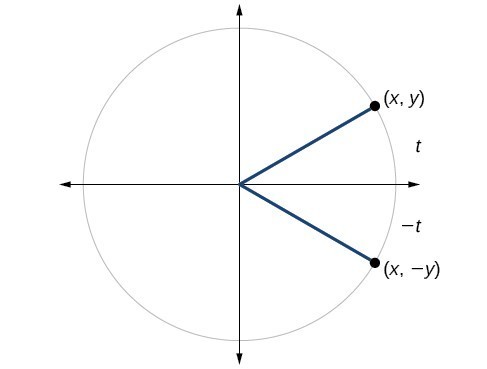

We can test whether a trigonometric function is even or odd by drawing a unit circle with a positive and a negative angle, as in Figure 7. The sine of the positive angle is [latex]y[/latex]. The sine of the negative angle is −y. The sine function, then, is an odd function. We can test each of the six trigonometric functions in this fashion. The results are shown in in the table below.

Figure 25

| [latex]\begin{array}{l}\sin t=y\hfill \\ \sin \left(-t\right)=-y\hfill \\ \sin t\ne \sin \left(-t\right)\hfill \end{array}[/latex] | [latex]\begin{array}{l}\text{cos}t=x\hfill \\ \cos \left(-t\right)=x\hfill \\ \cos t=\cos \left(-t\right)\hfill \end{array}[/latex] | [latex]\begin{array}{l}\text{tan}\left(t\right)=\frac{y}{x}\hfill \\ \tan \left(-t\right)=-\frac{y}{x}\hfill \\ \tan t\ne \tan \left(-t\right)\hfill \end{array}[/latex] |

| [latex]\begin{array}{l}\sec t=\frac{1}{x}\hfill \\ \sec \left(-t\right)=\frac{1}{x}\hfill \\ \sec t=\sec \left(-t\right)\hfill \end{array}[/latex] | [latex]\begin{array}{l}\csc t=\frac{1}{y}\hfill \\ \csc \left(-t\right)=\frac{1}{-y}\hfill \\ \csc t\ne \csc \left(-t\right)\hfill \end{array}[/latex] | [latex]\begin{array}{l}\cot t=\frac{x}{y}\hfill \\ \cot \left(-t\right)=\frac{x}{-y}\hfill \\ \cot t\ne cot\left(-t\right)\hfill \end{array}[/latex] |

A General Note: Even and Odd Trigonometric Functions

An even function is one in which [latex]f\left(-x\right)=f\left(x\right)[/latex].

An odd function is one in which [latex]f\left(-x\right)=-f\left(x\right)[/latex].

Cosine and secant are even:

[latex]\begin{gathered}\cos \left(-t\right)=\cos t \\ \sec \left(-t\right)=\sec t \end{gathered}[/latex]

Sine, tangent, cosecant, and cotangent are odd:

[latex]\begin{gathered}\sin \left(-t\right)=-\sin t \\ \tan \left(-t\right)=-\tan t \\ \csc \left(-t\right)=-\csc t \\ \cot \left(-t\right)=-\cot t \end{gathered}[/latex]

Example 4: Using Even and Odd Properties of Trigonometric Functions

If the [latex]\sec t=2[/latex], what is the [latex]\sec (-t)[/latex]?

Try It

If the [latex]\cot t=\sqrt{3}[/latex], what is [latex]\cot (-t)[/latex]?

Recognize and Use Fundamental Identities

We have explored a number of properties of trigonometric functions. Now, we can take the relationships a step further, and derive some fundamental identities. Identities are statements that are true for all values of the input on which they are defined. Usually, identities can be derived from definitions and relationships we already know. For example, the Pythagorean Identity we learned earlier was derived from the Pythagorean Theorem and the definitions of sine and cosine.

A General Note: Fundamental Identities

We can derive some useful identities from the six trigonometric functions. The other four trigonometric functions can be related back to the sine and cosine functions using these basic relationships:

[latex]\tan t=\frac{\sin t}{\cos t}[/latex]

[latex]\sec t=\frac{1}{\cos t}[/latex]

[latex]\csc t=\frac{1}{\sin t}[/latex]

[latex]\cot t=\frac{1}{\tan t}=\frac{\cos t}{\sin t}[/latex]

Example 11: Using Identities to Evaluate Trigonometric Functions

- Given [latex]\sin \left(45^\circ \right)=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2},\cos \left(45^\circ \right)=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}[/latex], evaluate [latex]\tan \left(45^\circ \right)[/latex].

- Given [latex]\sin \left(\frac{5\pi }{6}\right)=\frac{1}{2},\cos\left(\frac{5\pi }{6}\right)=-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}[/latex], evaluate [latex]\sec \left(\frac{5\pi }{6}\right)[/latex].

Try It

Evaluate [latex]\csc\left(\frac{7\pi }{6}\right)[/latex].

Example 12: Using Identities to Simplify Trigonometric Expressions

Simplify [latex]\frac{\sec t}{\tan t}[/latex].

Try It

Simplify [latex]\tan t\left(\cos t\right)[/latex].

Alternate Forms of the Pythagorean Identity

We can use these fundamental identities to derive alternative forms of the Pythagorean Identity, [latex]{\cos }^{2}t+{\sin }^{2}t=1[/latex]. One form is obtained by dividing both sides by [latex]{\cos }^{2}t:[/latex]

The other form is obtained by dividing both sides by [latex]{\sin }^{2}t:[/latex]

A General Note: Alternate Forms of the Pythagorean Identity

[latex]1+{\tan }^{2}t={\sec }^{2}t[/latex]

[latex]{\cot }^{2}t+1={\csc }^{2}t[/latex]

Example 13: Using Identities to Relate Trigonometric Functions

If [latex]\text{cos}\left(t\right)=\frac{12}{13}[/latex] and [latex]t[/latex] is in quadrant IV, as shown in Figure 8, find the values of the other five trigonometric functions.

Figure 26

Try It

If [latex]\sec \left(t\right)=-\frac{17}{8}[/latex] and [latex]0