Economic transformations and technological advances moved ever more Americans into cities. Industry advanced onward and drew millions of workers into the new cities. Manufacturing needed large pools of labor and advanced infrastructure only available in the cities, where electricity kept the lights on and transported ever growing numbers of people along electric trolley lines and upward in elevators inside the towering skyscrapers made possible by new mass produced steel and advanced engineering. America’s urban population increased seven fold in the half-century after the Civil War. Soon the United States had more large cities than any country in the world. The 1920 U.S. census revealed that, for the first time, a majority of Americans lived in urban areas.

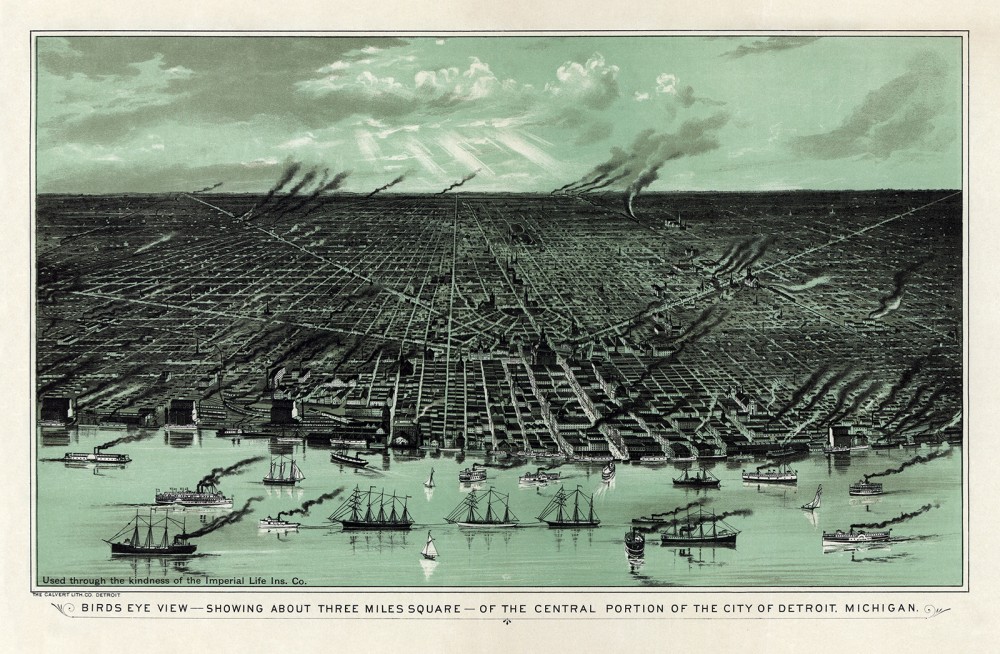

Detroit, Michigan, began to prosper as an industrial city and major transportation hub by the mid to late nineteenth century. It would continue to grow throughout the early to mid-twentieth century as Henry Ford and others pioneered the automobile industry and made Detroit the automobile capital of the world—hence its nickname “Motor City.” Calvert Lith. Co., “Birds eye view—showing about three miles square—of the central portion of the city of Detroit, Michigan,” 1889. Wikimedia.

Much of America’s urban growth came from the millions of immigrants pouring into the nation. Between 1870 and 1920, over 25 million immigrants arrived in the United States. At first streams of migration continued patterns set before the Civil War but, by the turn of the twentieth century, new groups such as Italians, Poles, and Eastern European Jews made up larger percentages of arrivals while Irish and German immigration dissipated. This massive movement of people to the United States was influenced by a number of causes, what historians typically call “push” and “pull” factors. In other words, certain conditions in home countries encouraged people to leave and other factors encouraged them to choose the United States (instead of say, Canada, Australia, or Argentina) as their destination. For example, a young husband and wife living in Sweden in the 1880s and unable to purchase farmland might read an advertisement for inexpensive land in the American Midwest and choose to sail to the United States. A young Italian might hope to labor in a steel factory for several years and save up enough money to return home and purchase land for a family. Or a Russian Jewish family, eager to escape European pogroms, might look to the United States as a sanctuary. Or perhaps a Japanese migrant might hear of fertile farming land on the West Coast and choose to sail for California. There were numerous factors that pushed people out of their homelands, but by far the most important factor drawing immigrants to the United States between 1880 and 1920 was the maturation of American capitalism. Immigrants poured into the cities looking for work.

Cities such as New York, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and St. Louis attracted large number of immigrants eager to work in their factories. By 1890, in most large northern cities, immigrants and their children amounted to roughly 60 percent of the population, and reached as high as 80 or 90 percent. Some immigrants, often from Italy or the Balkans, hoped to return home with enough money to purchase land. But for those who stayed, historians have long debated how these immigrants adjusted to their new home. Did the new arrivals mix together in the American “melting pot” and assimilate—becoming just like those people already in the United States—or did they retain—and sometimes even strength—their traditional ethnic identities? The answer lies somewhere in the middle. Immigrant groups formed vibrant societies and organizations to ease the transition to their new home. Examples included Italian workmen’s clubs, Eastern European Jewish mutual-aid societies, and Polish Catholic Churches. Newspapers published in dozens of languages. Ethnic communities provided cultural space for immigrants to maintain their arts, languages, and traditions while also facilitating even more immigrants. Historians label this process chain migration. Recently arrived immigrants wrote home and welcomed more immigrants that arrived in American cities knowing they could find friendly communities and live near other immigrants from their home country and, often, even from their home regions.

As the country’s busiest immigrant inspection station from the late nineteenth through mid-twentieth century, Ellis Island operated a massive medical service through the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital (seen in the photograph). Symbols of various diseases (physical and mental) were placed on immigrants’ clothing using chalk, and many were able to enter the country only through wiping off or concealing the chalk marks. Photograph of the Immigrant Hospital at Ellis Island, 1913. Wikimedia.

Cities and the people that populated them became the targets of critics. Many reformers criticized American municipal governments as corrupt institutions that did little to improve city life and much to enrich party bosses. New York City’s Democratic Party machine, popularly known as Tammany Hall, seemed to embody all of the worst of city machines. In 1903, journalist William Riordon published a book, Plunkitt of Tammany Hall, which chronicled the activities of ward heeler George Washington Plunkitt. Plunkitt elaborately explained to Riordon the difference between “honest graft” and “dishonest graft:” “I made my pile in politics, but, at the same time, I served the organization and got more big improvements for New York City than any other livin’ man.” While exposing the corruption of New York City government, Riordon also revealed the hard work Plunkitt undertook on behalf of his largely immigrant constituency. On a typical day, Riordon wrote, Plunkitt was awakened at 2:00 AM to bail out a saloon-keeper who stayed open too late, was awakened again at 6:00 AM because of a fire in the neighborhood and spent time finding lodgings for the families displaced by the fire, because, as Riordon noted, fires like this were “considered great vote-getters.” After spending the rest of the morning in court to secure the release of several of his constituents who had run afoul of the law, Plunkitt found jobs for four unemployed men, attended an Italian funeral, visited a church social, and dropped in on a Jewish wedding. He finally returned home to bed at midnight.

As Riordon’s account makes clear, Plunkitt and other Tammany officials had direct and daily connections to the needs of their largely immigrant constituents. Although corrupt urban officials like Plunkitt did little to solve the root causes of urban vice and poverty, they did what they could to relieve its effects. Plunkitt and his ilk thus left a mixed legacy—on the one hand responsive to their constituents’ needs, on the other doing little to solve the underlying issues that created these needs.

Tammany Hall arose in the eighteenth century as a working-class alternative to elite fraternal organizations such as the Society of the Cincinnati that formed after the American Revolution. The “Society of Tammany or the Columbian Order in the City of New York” was established in 1786 by a group of artisans and mechanics for social and philanthropic purposes. Like fraternal orders of any age, Tammany was born with peculiar rituals: members were “braves” who elected a board of thirteen “sachems” who picked a Grand Sachem who led the whole “wigwam.” Members donned Indian regalia for national holiday parades, which ended with ample dining and drink. But then politics intruded. Tammany support for the French Revolution alienated Federalist members, tilting the society toward the emerging Democratic Republican Party by the mid-1790s. Soon Tammany affiliated with such leading Democratic politicians as Aaron Burr and promoted immigrant (especially Irish) rights, universal male suffrage, abolition of imprisonment for debt, public education, and other rising populist causes.

Tammany Hall was at its political height in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, around the time this photograph of the building at Tammany Hall and 14th St. West was taken. It practically controlled Democratic Party nominations and political patronage in New York City from the 1850s through the 1930s. Irving Underhill (photographer),” c. 1914. Tammany Hall & 14th St. West,” Library of Congress.

By the time Tammany opened its first hall (after meeting in a succession of taverns and rented spaces) on Nassau Street in 1812, it was a full-fledged political organization, dominant in city politics, influential in state politics, and a player in national politics. In 1868, it moved uptown to an ornate new hall near Union Square where it hosted that year’s Democratic National Convention. Tammany Hall entered into the peak of its powers.

But politics led to power and corruption followed. The most notorious of Tammany’s corruptions became the reign of William “Boss” Tweed, who became Grand Sachem in 1863. In the decades leading to Tweed’s ascension, Tammany had gradually gained control of the Common Council, the city’s legislative body, whose compliant members awarded government jobs, contracts, licenses, and franchises to the Tammany faithful, mainly tens of thousands of immigrant Irish. The first Tammany mayor was elected in 1854; the last left office nearly a century later. Tweed, as state senator and holder of various appointive city offices, made patronage and graft common practice. Entire branches of municipal, county, and state government—judicial, legislative, fiscal, and executive—became organs of Tammany power. By the time crusading journalists and politicians dispatched Tweed in 1871, his “Tammany Ring” had defrauded city government, through bribery, kickbacks, padded and fictitious expenses, bogus contracts, and other means, of upwards of $200 million ($8 billion today).

On the other hand, the copious public works projects that were the source of Tammany’s bounty also provided essential infrastructure and public services for the city’s rapidly expanding population. Water, sewer, and gas lines; schools, hospitals, civic buildings, and museums; police and fire departments; roads, parks (notably Central Park), and bridges (notably the Brooklyn Bridge): all in whole or part can be credited to Tammany’s reign. An honest government arguably could not have built as much.

Tweed’s fall (after civil and criminal trials and international flight, he died of pneumonia in a city jail in 1878) hardly spelled the demise of Tammany. While Tammany “reformers” cut back on the most outright and obvious crookedness, they also refined Tammany’s political machinery and managed another half century of less scandalous but more rigorous control of city and state government. An 1894 state corruption investigation dented Tammany’s power but at the turn of the twentieth century Tammany still controlled an estimated 60,000 government jobs. In the early 1900s, Tammany aligned itself with the Progressive and good government reform movements, later boosting the national profiles of four-term governor and 1928 Democratic presidential candidate Al Smith and other Tammany politicians.

Beyond New York, Tammany Hall was a catch phrase for political corruption, and, although its corruption was legendary, it was also creature of its time, a cause of New York’ rise. Tammany Hall was a model of urban political organization and was useful in many ways for exercising power and building necessary improvements for a rapidly expanding city where weaker authority may have failed. Egregious in its excesses but effective in its purposes, it was perhaps much like nineteenth-century New York itself. All the while, conflicts over urban problems and city government dominate local politics, and pitting good-government reformers (typically affluent, educated Protestant Republicans) against the masses of urban residents (typically immigrant Catholics and Jews who voted Democratic).

Americans would become consumed by the “urban crisis,” and progressive reformers would begin in the exploration of urban problems and the promotion of municipal reform. But Americans also expressed increasing concern over the declining quality of life in rural areas. While the cities boomed, however, rural worlds languished. Many, such as Jack London in books like The Valley of the Moon, romanticized the countryside and celebrated rural life while wondering what had been lost in urban life, many American social scientists increasingly displayed a fascination with communal decay and immorality in rural places, indicative of a developing distaste towards rural culture as well as the cultural allure of city life among many urban elites. Sociologist Kenyon Butterfield, concerned by the sprawling nature of industrial cities and suburbs, expressed concern about the eroding position of rural citizens and farmers, noting that “agriculture does not hold the same relative rank among our industries that it did in former years.” Butterfield saw “the farm problem” as connected “with the whole question of democratic civilization” with rural depopulation and urban expansion threatening traditional American values. Others saw rural places and industrial cities as linked through shared economic interest which necessitated their preservation in the face of residential sprawl. Liberty Hyde Bailey, a botanist and rural scholar selected by Theodore Roosevelt to chair a federal Commission on Country Life in 1907, concluded that “every agricultural question is a city question, and every producers problem is a consumers problem,” noting the link between economic exchange and community development in rural places as they became less agrarian and more residential.

Many began to long for a middle path between the cities and the country. At the start of the twentieth century, newer suburban communities in the rural hinterlands of American cities such as Los Angeles defined themselves in opposition to urban crowding. Americans contemplated the complicated relationships between rural places, suburban living, and urban spaces. Certainly, Los Angeles was a model for the suburban development of rural places. Dana Barlett, a social reformer in Los Angeles, noted that Los Angeles, stretching across dozens of small towns even at the start of the twentieth century, was “a better city” because of its residential identity as a “city of homes.” This language was seized upon in many rural suburbs. In one of these small towns on the outskirts of Los Angeles, Glendora, local leaders were concerned about the reordering of rural spaces and the agricultural production of the surrounding countryside. Members of Glendora’s Chamber of Commerce reported their desire to keep “Glendora as it is” and were “loath as anyone to see it become cosmopolitan” or racially and ethnically heterogeneous like much of the surrounding countryside. Instead, town leaders argued that in order to have Glendora “grow along the lines necessary to have it remain an enjoyable city of homes,” the town’s leaders needed to “bestir ourselves to direct its growth” by encouraging further residential development at expense of agriculture. The citrus colonias that surrounded Glendora at this time, populated mostly by immigrant farm workers and their families from Japan, the Philippines, and Mexico would ultimately be destroyed as Glendora grew as a residential town in the following decades.

Candela Citations

- American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html. Project: American Yawp. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike