Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How is the presidency personalized?

- What powers does the Constitution grant to the president?

- How can Congress and the judiciary limit the president’s powers?

- How is the presidency organized?

- What is the bureaucratizing of the presidency?

The presidency is seen as the heart of the political system. It is personalized in the president as advocate of the national interest, chief agenda-setter, and chief legislator.[1] Scholars evaluate presidents according to such abilities as “public communication,” “organizational capacity,” “political skill,” “policy vision,” and “cognitive skill.”[2] The media too personalize the office and push the ideal of the bold, decisive, active, public-minded president who altruistically governs the country.[3]

The Media and the President

News depictions of the White House also focus on the person of the president. They portray a “single executive image” with visibility no other political participant can boast. Presidents usually get positive coverage during crises foreign or domestic. The news media depict them speaking for and symbolically embodying the nation: giving a State of the Union address, welcoming foreign leaders, traveling abroad, representing the United States at an international conference. Ceremonial events produce laudatory coverage even during intense political controversy.

The media are fascinated with the personality and style of individual presidents. They attempt to pin them down. Sometimes, the analyses are contradictory. In one best-selling book, Bob Woodward depicted President George W. Bush as, in the words of reviewer Michiko Kakutani, “a judicious, resolute leader . . . firmly in control of the ship of state.” In a subsequent book, Woodward described Bush as “passive, impatient, sophomoric, and intellectual incurious . . . given to an almost religious certainty that makes him disinclined to rethink or re-evaluate decisions.”[4]

This media focus tells only part of the story.[5] The president’s independence and ability to act are constrained in several ways, most notably by the Constitution.

The Presidency in the Constitution

Article II of the Constitution outlines the office of president. Specific powers are few; almost all are exercised in conjunction with other branches of the federal government.

Table 1. Bases for Presidential Powers in the Constitution

| Article I, Section 7, Paragraph 2 | Veto |

| Pocket veto | |

| Article II, Section 1, Paragraph 1 | “The Executive Power shall be vested in a President…” |

| Article II, Section 1, Paragraph 7 | Specific presidential oath of office stated explicitly (as is not the case with other offices) |

| Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 1 | Commander in chief of armed forces and state militias |

| Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 1 | Can require opinions of departmental secretaries |

| Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 1 | Reprieves and pardons for offences against the United States |

| Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 2 | Make treaties |

| appoint ambassadors, executive officers, judges | |

| Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 3 | Recess appointments |

| Article II, Section 3 | State of the Union message and recommendation of legislative measures to Congress |

| Convene special sessions of Congress | |

| Receive ambassadors and other ministers | |

| “He shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed” |

Presidents exercise only one power that cannot be limited by other branches: the pardon. So controversial decisions like President Gerald Ford’s pardon of his predecessor Richard Nixon for “crimes he committed or may have committed” or President Jimmy Carter’s blanket amnesty to all who avoided the draft during the Vietnam War could not have been overturned.

Presidents have more powers and responsibilities in foreign and defense policy than in domestic affairs. They are the commanders in chief of the armed forces; they decide how (and increasingly when) to wage war. Presidents have the power to make treaties to be approved by the Senate; the president is America’s chief diplomat. As head of state, the president speaks for the nation to other world leaders and receives ambassadors.

Link: Presidential Power

The Constitution directs presidents to be part of the legislative process. In the annual State of the Union address, presidents point out problems and recommend legislation to Congress. Presidents can convene special sessions of Congress, possibly to “jump-start” discussion of their proposals. Presidents can veto a bill passed by Congress, returning it with written objections. Congress can then override the veto. Finally, the Constitution instructs presidents to be in charge of the executive branch. Along with naming judges, presidents appoint ambassadors and executive officers. These appointments require Senate confirmation. If Congress is not in session, presidents can make temporary appointments known as recess appointments without Senate confirmation, good until the end of the next session of Congress.

The Constitution’s phrase “he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed” gives the president the job to oversee the implementation of laws. Thus presidents are empowered to issue executive orders to interpret and carry out legislation. They supervise other officers of the executive branch and can require them to justify their actions.

Congressional Limitations on Presidential Power

Almost all presidential powers rely on what Congress does (or does not do). Presidential executive orders implement the law but Congress can overrule such orders by changing the law. And many presidential powers are delegated powers that Congress has accorded presidents to exercise on its behalf—and that it can cut back or rescind. See how Donald Trump compares to other presidents after 100 days in office.

Congress can challenge presidential powers single-handedly. One way is to amend the Constitution. The Twenty-Second Amendment was enacted in the wake of the only president to serve more than two terms, the powerful Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR). Presidents now may serve no more than two terms. The last presidents to serve eight years, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush, quickly became “lame ducks” after their reelection and lost momentum toward the ends of their second terms, when attention switched to contests over their successors.

Impeachment and removal (click on the link and watch the video for potential exam questions)

gives Congress “sole power” to remove presidents (among others) from office.[6] It works in two stages. The House decides whether or not to accuse the president of wrongdoing. If a simple majority in the House votes to impeach the president, the Senate acts as jury, House members are prosecutors, and the chief justice presides. A two-thirds vote by the Senate is necessary for conviction, the punishment for which is removal and disqualification from office.

Prior to the 1970s, presidential impeachment was deemed the founders’ “rusted blunderbuss that will probably never be taken in hand again.”[7] Only one president (Andrew Johnson in 1868) had been impeached—over policy disagreements with Congress on the Reconstruction of the South after the Civil War. Johnson avoided removal by a single senator’s vote.

https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/5/12/15615066/impeachment-trump-process-history

Since the 1970s, the blunderbuss has been dusted off. A bipartisan majority of the House Judiciary Committee recommended the impeachment of President Nixon in 1974. Nixon surely would have been impeached and convicted had he not resigned first. President Clinton was impeached by the House in 1998, though acquitted by the Senate in 1999, for perjury and obstruction of justice in the Monica Lewinsky scandal.

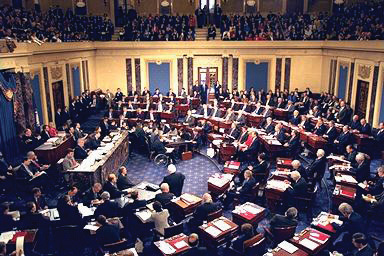

Bill Clinton was only the second US president to be impeached for “high crimes and misdemeanors” and stand trial in the Senate. Not surprisingly, in this day of huge media attention to court proceedings, the presidential impeachment trial was covered live by television and became endless fodder for twenty-four-hour-news channels. Chief Justice William Rehnquist presided over the trial. The House “managers” (i.e., prosecutors) of the case are on the left, the president’s lawyers on the right.

Much of the public finds impeachment a standard part of the political system. For example, a June 2005 Zogby poll found that 42 percent of the public agreed with the statement “If President Bush did not tell the truth about his reasons for going to war with Iraq, Congress should consider holding him accountable through impeachment.”[8]

Impeachment can be a threat to presidents who chafe at congressional opposition or restrictions. All three presidents who faced impeachment (Richard Nixon) or were impeached (Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton) had been accused by members of Congress of abuse of power well before allegations of law-breaking. Impeachment is handy because it refers only vaguely to official misconduct: “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.”

From Congress’s perspective, impeachment can work. Nixon resigned because he knew he would be removed from office. Even presidential acquittals help Congress out. Impeachment forced Johnson to pledge good behavior and thus “succeeded in its primary goal: to safeguard Reconstruction from presidential obstruction.”[9] Clinton had to go out of his way to assuage congressional Democrats, who had been far from content with a number of his initiatives; by the time the impeachment trial was concluded, the president was an all-but-lame duck.

Judicial Limitations on Presidential Power

Presidents claim inherent powers not explicitly stated but that are intrinsic to the office or implied by the language of the Constitution. They rely on three key phrases. First, in contrast to Article I’s detailed powers of Congress, Article II states that “The Executive Power shall be vested in a President.” Second, the presidential oath of office is spelled out, implying a special guardianship of the Constitution. Third, the job of ensuring that “the Laws be faithfully executed” can denote a duty to protect the country and political system as a whole.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court can and does rule on whether presidents have inherent powers. Its rulings have both expanded and limited presidential power. For instance, the justices concluded in 1936 that the president, the embodiment of the United States outside its borders, can act on its behalf in foreign policy.

But the court usually looks to congressional action (or inaction) to define when a president can invoke inherent powers. In 1952, President Harry Truman claimed inherent emergency powers during the Korean War. Facing a steel strike he said would interrupt defense production, Truman ordered his secretary of commerce to seize the major steel mills and keep production going. The Supreme Court rejected this move: “the President’s power, if any, to issue the order must stem either from an act of Congress or from the Constitution itself.”[10]

The Vice Presidency

President Donald Trump and Vice President Mike Pence

Only two positions in the presidency are elected: the president and vice president. With ratification of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment in 1967, a vacancy in the latter office may be filled by the president, who appoints a vice president subject to majority votes in both the House and the Senate. This process was used twice in the 1970s. Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned amid allegations of corruption; President Nixon named House Minority Leader Gerald Ford to the post. When Nixon resigned during the Watergate scandal, Ford became president—the only person to hold the office without an election—and named former New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller vice president.

The vice president’s sole duties in the Constitution are to preside over the Senate and cast tie-breaking votes, and to be ready to assume the presidency in the event of a vacancy or disability. Eight of the forty-three presidents had been vice presidents who succeeded a dead president (four times from assassinations). Otherwise, vice presidents have few official tasks. The first vice president, John Adams, told the Senate, “I am Vice President. In this I am nothing, but I may be everything.” More earthily, FDR’s first vice president, John Nance Garner, called the office “not worth a bucket of warm piss.”

In recent years, vice presidents are more publicly visible and have taken on more tasks and responsibilities. Ford and Rockefeller began this trend in the 1970s, demanding enhanced day-to-day responsibilities and staff as conditions for taking the job. Vice presidents now have a West Wing office, are given prominent assignments, and receive distinct funds for a staff under their control parallel to the president’s staff.[11]

Arguably the most powerful occupant of the office ever was Dick Cheney. This former doctoral candidate in political science (at the University of Wisconsin) had been a White House chief of staff, member of Congress, and cabinet secretary. He possessed an unrivaled knowledge of the power relations within government and of how to accumulate and exercise power. As George W. Bush’s vice president, he had access to every cabinet and subcabinet meeting he wanted to attend, chaired the board charged with reviewing the budget, took on important issues (security, energy, economy), ran task forces, was involved in nominations and appointments, and lobbied Congress.[12]

Organizing the Presidency

The presidency is organized around two offices. They enhance but also constrain the president’s power.

The Executive Office of the President

The Executive Office of the President (EOP) is an umbrella organization encompassing all presidential staff agencies. Most offices in the EOP, such as the Office of the Vice President, the National Security Council, and the Office of Management and Budget, are established by law; some positions require Senate confirmation.

Learn about the EOP here.

Inside the EOP is the White House Office (WHO). It contains the president’s personal staff of assistants and advisors; most are exempt from Congress’s purview. Though presidents have a free hand with the personnel and structure of the WHO, its organization has been the same for decades. Starting with Nixon in 1969, each president has named a chief of staff to head and supervise the White House staff, a press secretary to interact with the news media, and a director of communication to oversee the White House message. The national security advisor is well placed to become the most powerful architect of foreign policy, rivaling or surpassing the secretary of state. New offices, such as President Bush’s creation of an office for faith-based initiatives, are rare; such positions get placed on top of or alongside old arrangements.

Even activities of a highly informal role such as the first lady, the president’s spouse, are standardized. It is no longer enough for them to host White House social events. They are brought out to travel and campaign. They are presidents’ intimate confidantes, have staffers of their own, and advocate popular policies (e.g., Lady Bird Johnson’s highway beautification, Nancy Reagan’s antidrug crusade, and Barbara Bush’s literacy programs). Hillary Rodham Clinton faced controversy as first lady by defying expectations of being above the policy fray; she was appointed by her husband to head the task force to draft a legislative bill for a national health-care system. Clinton’s successor, Laura Bush, returned the first ladyship to a more social, less policy-minded role. Michelle Obama’s cause is healthy eating. She has gone beyond advocacy to having Walmart lower prices on the fruit and vegetables it sells and reducing the amount of fat, sugar, and salt in its foods.

Bureaucratizing the Presidency

The media and the public expect presidents to put their marks on the office and on history. But “the institution makes presidents as much if not more than presidents make the institution.”[13]

The presidency became a complex institution starting with FDR, who was elected to four terms during the Great Depression and World War II. Prior to FDR, presidents’ staffs were small. As presidents took on responsibilities and jobs, often at Congress’s initiative, the presidency grew and expanded.

Not only is the presidency bigger since FDR, but the division of labor within an administration is far more complex. Fiction and nonfiction media depict generalist staffers reporting to the president, who makes the real decisions. But the WHO is now a miniature bureaucracy. The WHO’s first staff in 1939 consisted of eight generalists: three secretaries to the president, three administrative assistants, a personal secretary, an executive clerk. Since the 1980s, the WHO has consisted of around eighty staffers; almost all either have a substantive specialty (e.g., national security, women’s initiatives, environment, health policy) or emphasize specific activities (e.g., White House legal counsel, director of press advance, public liaison, legislative liaison, chief speechwriter, director of scheduling). The White House Office adds another organization for presidents to direct—or lose track of.

The large staff in the White House, and the Old Executive Office Building next door, is no guarantee of a president’s power. These staffers “make a great many decisions themselves, acting in the name of the president. In fact, the majority of White House decisions—all but the most crucial—are made by presidential assistants.”[14]

Most of these labor in anonymity unless they make impolitic remarks. For example, two of President Bush’s otherwise obscure chief economic advisors got into hot water, one for (accurately) predicting that the cost of war in Iraq might top $200 billion, another for praising the outsourcing of jobs.[15] Relatively few White House staffers—the chief of staff, the national security advisor, the press secretary—become household names in the news, and even they are quick to be quoted saying, “as the president has said” or “the president decided.” But often what presidents say or do is what staffers told or wrote for them to say or do.

Comparing Content: Days in the Life of the White House

On April 25, 2001, President George W. Bush was celebrating his first one hundred days in office. He sought to avoid the misstep of his father who ignored the media frame of the first one hundred days as the make-or-break period for a presidency and who thus seemed confused and aimless.

As part of this campaign, Bush invited Stephen Crowley, a New York Times photographer, to follow him and present, as Crowley wrote in his accompanying text, “an unusual behind-the-scenes view of how he conducts business.”[16] Naturally, the photos implied that the White House revolves completely around the president. At 6:45 a.m., “the White House came to life”—when a light came on in the president’s upstairs residence. The sole task shown for Bush’s personal assistant was peering through a peephole to monitor the president’s national security briefing. Crowley wrote “the workday ended 15 hours after it began,” after meetings, interviews, a stadium speech, and a fundraiser.

We get a different understanding of how the White House works from following not the president but some other denizen of the West Wing around for a day or so. That is what filmmaker Theodore Bogosian did: he shadowed Clinton’s then press secretary Joe Lockhart for a few days in mid-2000 with a high-definition television camera. In the revealing one-hour video, The Press Secretary, activities of the White House are shown to revolve around Lockhart as much as Crowley’s photographic essay showed they did around Bush. Even with the hands-on Bill Clinton, the video raises questions about who works for whom. Lockhart is shown devising tag lines, even policy with his associates in the press office. He instructs the president what to say as much as the other way around. He confides to the camera he is nervous about letting Clinton speak off-the-cuff.

Of course, the White House does not revolve around the person of the press secretary. Neither does it revolve entirely around the person of the president. Both are lone individuals out of many who collectively make up the institution known as the presidency.

Key Takeaways

The entertainment and news media personalize the presidency, depicting the president as the dynamic center of the political system. The Constitution foresaw the presidency as an energetic office with one person in charge. Yet the Constitution gave the office and its incumbent few powers, most of which can be countered by other branches of government. The presidency is bureaucratically organized and includes agencies, offices, and staff. They are often beyond a president’s direct control.

Candela Citations

- 21st Century American Government. Authored by: Anonymous. Provided by: Lardbucket. Located at: http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/21st-century-american-government-and-politics/s17-01-the-powers-of-the-presidency.html. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Martin Sheen. Authored by: Chief Journalist Daniel Ross. Provided by: U.S. Navy. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Martinsheennavy.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- President Bush at Mount Rushmore. Provided by: Executive Office of the President of the United States. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bush_at_Mount_Rushmore.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- U.S. Senate in session. Authored by: Unknown. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Senate_in_session.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Jeffrey K. Tulis, The Rhetorical Presidency (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988). ↵

- Fred I. Greenstein, The Presidential Difference: Leadership Style from FDR to Barack Obama, 3rd ed. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009). ↵

- For presidential depictions in the media, see Jeff Smith, The Presidents We Imagine (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009). ↵

- Michiko Kakutani, “A Portrait of the President as the Victim of His Own Certitude,” review of State of Denial: Bush at War, Part III, by Bob Woodward, New York Times, September 30, 2006, A15; the earlier book is Bush at War (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002). ↵

- On the contrast of “single executive image” and the “plural executive reality,” see Lyn Ragsdale, Presidential Politics (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1993). ↵

- The language in the Constitution comes from Article I, Section 2, Clause 5, and Article I, Section 3, Clause 7. This section draws from Michael Les Benedict, The Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson(New York: Norton, 1973); John R. Labowitz, Presidential Impeachment (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1978); and Michael J. Gerhardt, The Federal Impeachment Process: A Constitutional and Historical Analysis, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000). ↵

- The early twentieth-century political scientist Henry Jones Ford quoted in John R. Labowitz, Presidential Impeachment (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1978), 91. ↵

- Polling Report, accessed July 7, 2005. ↵

- Michael Les Benedict, The Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson (New York: Norton, 1973), 139. ↵

- Respectively, United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp, 299 US 304 (1936); Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company v. Sawyer, 343 US 579 (1952). ↵

- Paul C. Light, Vice-Presidential Power: Advice and Influence in the White House (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984). ↵

- Barton Gellman and Jo Becker, “Angler: The Cheney Vice Presidency,” Washington Post, June 24, 2007, A1. ↵

- Lyn Ragsdale and John J. Theis III, “The Institutionalization of the American Presidency, 1924–92,” American Journal of Political Science 41, no. 4 (October 1997): 1280–1318 at 1316. See also John P. Burke, The Institutional Presidency, 2nd ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000). ↵

- John H. Kessel, Presidents, the Presidency, and the Political Environment(Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2001), 2. ↵

- Edmund L. Andrews, “Economics Adviser Learns the Principles of Politics,” New York Times, February 26, 2004, C4. ↵

- Stephen Crowley, “And on the 96th Day…,” New York Times, April 29, 2001, Week in Review, 3. ↵