Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How are American election campaigns organized?

- How are campaigns funded? What are the regulations that guide campaign fundraising and spending?

- How are political party nominees for president selected?

- What is the purpose of presidential nominating conventions?

- What is the Electoral College, and how does it work?

The presidential election gets the most prominent American campaign. It lasts the longest and receives far more attention from the media than any other election. The Constitution requires the president to be a natural-born U.S. citizen, at least thirty-five years old when taking office, and a resident of the United States for at least fourteen years. It imposed no limits on the number of presidential terms, but the first president, George Washington, established a precedent by leaving office after two terms. This stood until President Franklin D. Roosevelt won a third term in 1940 and a fourth in 1944. Congress then proposed, and the states ratified, the Twenty-Second Amendment to the Constitution, which limited the president’s term of office to two terms.

Campaign Organization

It takes the coordinated effort of a staff to run a successful campaign for office. The staff of paid professionals is headed by the campaign manager who oversees personnel, allocates expenditures, and develops strategy. The political director deals with other politicians, interest groups, and organizations supporting the candidate. The finance director helps the candidate raise funds directly and through a finance committee. The research director is responsible for information supporting the candidate’s position on issues and for research on the opponents’ statements, voting record, and behavior, including any vulnerabilities that can be attacked.

The press secretary promotes the candidate to the news media and at the same time works to deflect negative publicity. This entails briefing journalists, issuing press releases, responding to reporters’ questions and requests, and meeting informally with journalists. As online media have proliferated, the campaign press secretary’s job has become more complicated, as it entails managing the information that is disseminated on news websites, such as blogs like the Huffington Post, and social media, such as Facebook. Campaigns also have consultants responsible for media strategy, specialists on political advertising, and speech writers.

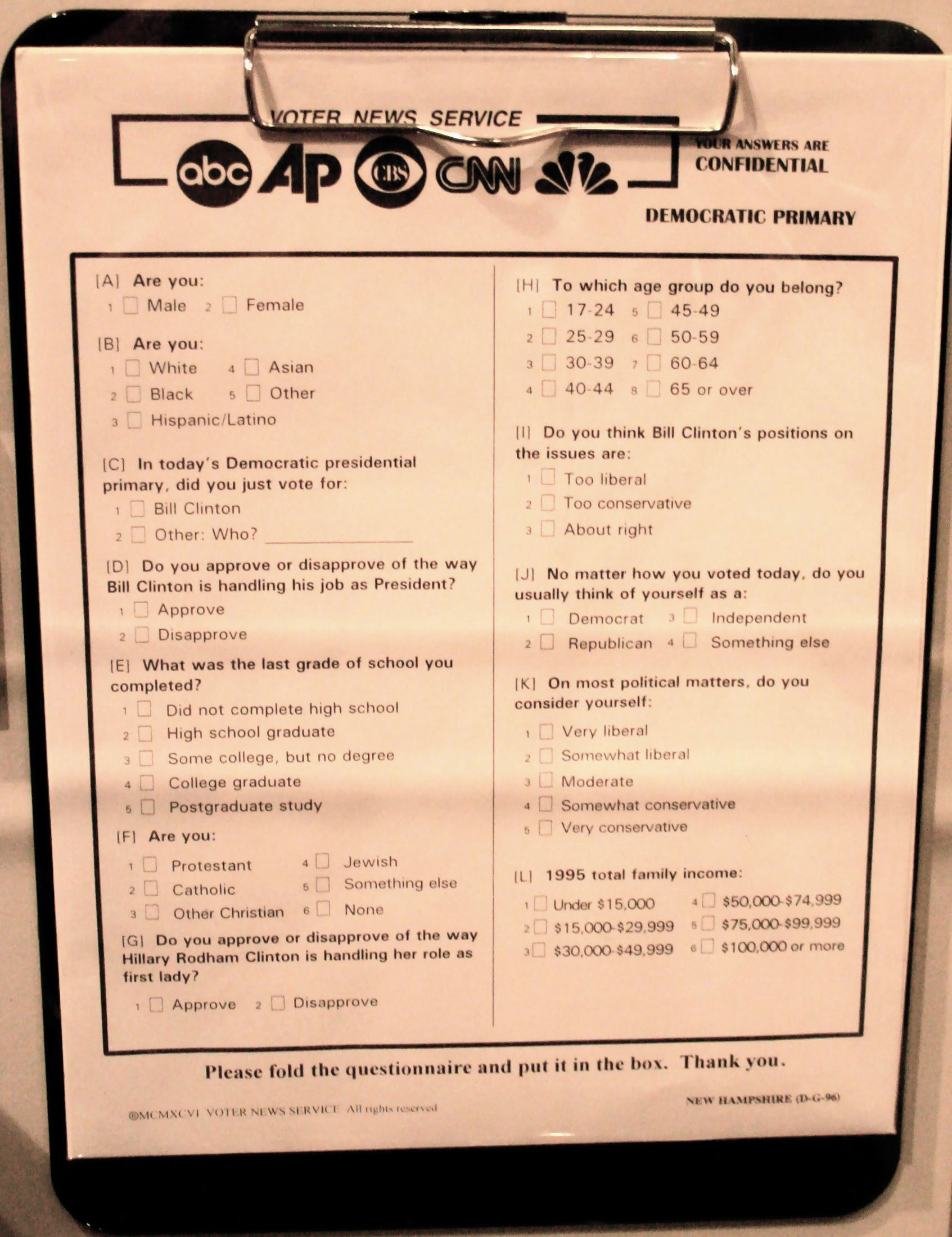

Outside the polls, some voters answer questions on exit polls that are used in media reports.

Pollsters are essential because campaigning without polls is like “flying without the benefit of radar.”[1] Polls conducted by campaigns, not to be confused with the media’s polls, can identify the types of people who support or oppose the candidate and those who are undecided. They can reveal what people know and feel about the candidates, the issues that concern them, and the most effective appeals to win their votes. Tracking polls measure shifts in public opinion, sometimes daily, in response to news stories and events. They test the effectiveness of the campaign’s messages, including candidates’ advertisements.

Relatedly, focus groups bring together a few people representative of the general public or of particular groups, such as undecided voters, to find out their reactions to such things as the candidate’s stump speech delivered at campaign rallies, debate performance, and campaign ads.

Funding Campaigns

“Money is the mother’s milk of politics,” observed the longtime and powerful California politician Jesse Unruh. The cost of organizing and running campaigns has risen precipitously. The 2008 presidential and congressional elections cost $5.3 billion dollars, a 25 percent increase over 2004.[2] Around 60 percent of this money goes for media costs, especially television advertising. The Campaign Finance Institute has a wealth of information about funding of American election campaigns.

Limiting Contributions and Expenditures

In an episode of The Simpsons, Homer’s boss tells him, “Do you realize how much it costs to run for office? More than any honest man could afford.”[3] Spurred by media criticisms and embarrassed by news stories of fund-raising scandals, Congress periodically passes, and the president signs, laws to regulate money in federal elections.

The Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) of 1971, amended in 1974, limited the amount of money that individuals, political parties, and political groups could contribute to campaigns and provided guidelines for how campaign funds could be spent. The FECA also provided a system of public financing for presidential campaigns. It required that campaigns report their financial information to a newly established enforcement institution, the Federal Elections Commission (FEC), which would make it public.

Opponents challenged the constitutionality of these laws in the federal courts, arguing that they restrict political expression.[4] In the 1976 case of Buckley v. Valeo, the Supreme Court upheld the limits on contributions and the reporting requirement but overturned all limits on campaign spending except for candidates who accept public funding for presidential election campaigns.[5] The Supreme Court argued that campaign spending was the equivalent of free speech, so it should not be constrained.

This situation lasted for around twenty years. “Hard money” (make sure to watch the short video and know the difference between hard, soft and dark money) that was contributed directly to campaigns was regulated through the FECA.

However, campaign advisors were able to exploit the fact that “soft money” given to the political parties for get-out-the-vote drives, party-building activities, and issue advertising was not subject to contribution limits. Soft money could be spent for political advertising as long as the ads did not ask viewers to vote for or against specific candidates. Nonparty organizations, such as interest groups, also could run issue ads as long as they were independent of candidate campaigns. The Democratic and Republican parties raised more than $262 million in soft money in 1996, much of which was spent on advertising that came close to violating the law.[6]

Republican National Committee Ad Featuring Presidential Candidate Bob Dole. The Republican National Committee used “soft money” to produce an ad that devoted fifty-six seconds to presidential candidate Bob Dole’s biography and only four seconds to issues. Similarly, the Democratic National Committee used “soft money” on ads that promoted candidate Bill Clinton. These ads pushed the limits of campaign finance laws, prompting a call for reform.

Congress responded with the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) of 2002, better known by the names of its sponsoring senators as McCain-Feingold. It banned soft-money contributions by political committees and prohibited corporations and labor unions from advocating for or against a candidate via broadcast, cable, or satellite prior to presidential primaries and the general election. A constitutional challenge to the law was mounted by Senate Majority Whip Mitch McConnell, who believed that the ban on advertising violated First Amendment free-speech rights. The law was upheld by a vote of 5–4 by the Supreme Court.[7] This decision was overruled in 2010 when the Supreme Court ruled that restricting independent spending by corporations in elections violated free speech.[8] The case concerned the rights of Citizens United, a conservative political group, to run a caustic ninety-minute film, Hillary: The Movie, on cable television to challenge Democratic candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton as she ran in the 2008 primary election campaign. The 5–4 decision divided the Supreme Court, as justices weighed the interests of large corporations against the Constitutional guarantee of free speech.[9]

In April 2011 comedic news anchor Stephen Colbert announced his intention to form a “super PAC” to expose loopholes in the campaign finance laws that allow corporations to form political actions committees, which can spend unlimited amounts of money in elections on advertising. Colbert testified in front of the FEC and was granted permission to form his PAC, which would be funded by Viacom, the media corporation that owns Comedy Central, which hosts The Colbert Report. The decision sparked concern that media organizations would be free to spend unlimited amounts of money in campaigns; however, the FEC’s decision imposed the strict limitation that Colbert could only show the ads on his program. Colbert announced the FEC’s decision to allow him to form a PAC to raise and spend funds in the 2012 election.

Sources of Funding

There are six main sources of funding for federal elections. These sources include individuals, political action committees, public funding, candidates’ contributions to their own campaigns, political party committees, and advocacy organizations or “527 committees.” Individuals contribute the most to election campaigns. Individual donations amounted to $1,330,861,724[10] for the 2008 presidential election cycle. People can give up to $2,300 to candidates for each primary, runoff, and general election; $28,500 annually to national political parties and $10,000 to each state party; $2,300 to a legal compliance fund; and as much as they want to a political action committee (PAC) and advocacy organizations. PACs were developed by business and labor to fund candidates. Politicians have also created PACs. They can give up to $5,000 per candidate per election. In 2008, they gave the second-largest amount: $5,221,500.

Presidential candidates can opt for public funding of their election campaigns. The funds come from an income tax check-off, where people can check a box to contribute $3 to a public funding account. To qualify for public funding, candidates must have raised $100,000 in amounts of $250 or less, with at least $5,000 from each of twenty states. The first $250 of every individual contribution is matched with public funds starting January 1 of the election year. However, candidates who take public funds must adhere to spending limits.

Presidential Candidate John McCain on the Campaign Trail in 2008. In 2008, Republican candidate John McCain criticized his Democratic opponent, Barack Obama, for failing to use public financing for his presidential bid, as he had promised. McCain felt disadvantaged by taking public funds because the law limits the amount of money he could raise and spend, while Obama was not subject to these restrictions.

Party committees at the national, state, and local level, as well as the parties’ Senate and House campaign committees, can give a Senate candidate a total of $35,000 for the primary and then general election and $5,000 to each House candidate. There is no limit on how much of their own money candidates can spend on their campaigns. Neither John McCain nor Barack Obama used personal funds for their own campaigns in 2008. Self-financed presidential candidates do not receive public funds.

Known as 527 committees after the Internal Revenue Service regulation authorizing them, advocacy groups, such as the pro-Democratic MoveOn.org and the pro-Republican Progress for America, can receive and spend unlimited amounts of money in federal elections as long as they do not coordinate with the candidates or parties they support and do not advocate the election or defeat of a candidate. They spent approximately $400 million in all races in the 2008 election cycle. In the wake of the Supreme Court decision supporting the rights of Citizens United to air Hillary: The Movie, spending by independent committees grew tremendously. The 527 committees spent $280 million in 2010, an increase of 130 percent from 2008.[11]

Caucuses and Primaries

Becoming a political party’s presidential nominee requires obtaining a majority of the delegates at the party’s national nominating convention. Delegates are party regulars, both average citizens who are active in party organizations and officeholders, who attend the national nominating conventions and choose the presidential nominee. The parties allocate convention delegates to the states, the District of Columbia, and to U.S. foreign territories based mainly on their total populations and past records of electing the party’s candidates. The Republican and Democratic nominating conventions are the most important, as third-party candidates rarely are serious contenders in presidential elections.

Most candidates begin building a campaign organization, raising money, soliciting support, and courting the media months, even years, before the first vote is cast. Soon after the president is inaugurated, the press begins speculating about who might run in the next presidential election. Potential candidates test the waters to see if their campaign is viable and if they have a chance to make a serious bid for the presidency.

Delegates to the party nominating conventions are selected through caucuses and primaries. Some states hold caucuses, often lengthy meetings of the party faithful who choose delegates to the party’s nominating convention. The first delegates are selected in the Iowa caucuses in January. Most convention delegates are chosen in primary elections in states. Delegates are allocated proportionally to the candidates who receive the most votes in the state. New Hampshire holds the first primary in January, ten months before the general election. More and more states front-load primaries—hold them early in the process—to increase their influence on the presidential nomination. Candidates and the media focus on the early primaries because winning them gives a campaign momentum.

Alert: test questions in video

The Democrats also have super delegates who attend their nominating convention. Super delegates are party luminaries, members of the National Committee, governors, and members of Congress. At the 2016 Democratic convention they made up approximately 18 percent of the delegates.

The National Party Conventions

The Democratic and Republican parties hold their national nominating conventions toward the end of the summer of every presidential election year to formally select the presidential and vice presidential candidates. The party of the incumbent president holds its convention last. Conventions are designed to inspire, unify, and mobilize the party faithful as well as to encourage people who are undecided, independent, or supporting the other party to vote for its candidates.[12] Conventions also approve the party’s platform containing its policy positions, proposals, and promises.

Selecting the party’s nominees for president and vice president is potentially the most important and exciting function of national conventions. But today, conventions are coronations as the results are already determined by the caucuses and primaries. The last presidential candidate not victorious on the first ballot was Democrat Adlai Stevenson in 1952. The last nominee who almost lacked enough delegates to win on the first ballot was President Gerald Ford at the 1976 Republican National Convention.

Presidential candidates choose the vice presidential candidate, who is approved by the convention. The vice presidential candidate is selected based on a number of criteria. He or she might have experience that compliments that of the presidential nominee, such as being an expert on foreign affairs while the presidential nominee concentrates on domestic issues. The vice presidential nominee might balance the ticket ideologically or come from a battleground state with many electoral votes. The choice for a vice presidential candidate can sometimes be met with dissent from party members.

Modern-day conventions are carefully orchestrated by the parties to display the candidates at their best and to demonstrate enthusiasm for the nominee. The media provide gavel-to-gavel coverage of conventions and replay highlights. As a result, candidates receive a postconvention “bounce” as their standing in the polls goes up temporarily just as the general election begins.

The Electoral College

The president and vice president are chosen by the Electoral College as specified in the Constitution. Voters do not directly elect the president but choose electors—representatives from their state who meet in December to select the president and vice president. To win the presidency, a candidate must obtain a majority of the electors, at least 270 out of the 538 total. The statewide winner-take-all by state system obliges them to put much of their time and money into swing states where the contest is close. Except for Maine and Nebraska, states operate under a winner-take-all system: the candidate with the most votes cast in the state, even if fewer than a majority, receives all its electoral votes.

What happens if no candidate wins 270 Electoral College votes? Make sure to watch this video for exam questions

Link: Electoral College Information

The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration has a resource for the Electoral College.

It is possible to win the election without winning the popular vote, as George W. Bush did in 2000 with about half a million fewer votes than Democrat Al Gore. The Electoral College decision depended on who won the popular vote in Florida, where voting was contested due to problems with ballots and voting machines. The voting in Florida was so close that the almost two hundred thousand ballots thrown out far exceeded Bush’s margin of victory of a few hundred votes.

Key Takeaways

Presidential elections involve caucuses, primaries, the national party convention, the general election, and the Electoral College. Presidential hopefuls vie to be their party’s nominee by collecting delegates through state caucuses and primaries. Delegates attend their party’s national nominating convention to select the presidential nominee. The presidential candidate selects his vice presidential running mate who is approved at the convention. Voters in the general election select electors to the Electoral College who select the president and vice president. It is possible for a candidate to win the popular vote and lose the general election.

Candela Citations

- 21st Century American Government. Authored by: Anonymous. Provided by: Lardbucket. Located at: http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/21st-century-american-government-and-politics/s15-03-presidential-elections.html. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Paul S. Herrnson, Congressional Elections: Campaigning at Home and in Washington, 5th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2007), 75. ↵

- Brody Mullins, “Cost of 2008 Election Cycle: $5.3 Billion,” Wall Street Journal, October 23, 2008. ↵

- “Two Cars in Every Garage, Three Eyes on Every Fish,” The Simpsons, November 1990. ↵

- See Bradley A. Smith, Unfree Speech: The Folly of Campaign Finance Reform (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001); and John Samples, The Fallacy of Campaign Finance Reform (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006). ↵

- Buckley v. Valeo, 424 US 1 (1976). ↵

- Dan Froomkin, “Special Report: Campaign Finance: Overview Part 4, Soft Money—A Look at the Loopholes,” Washington Post, September 4, 1998. ↵

- McConnell v. Federal Election Commission, 540 US 93 (2003). ↵

- Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 130 S.Ct. 876 (2010). ↵

- Adam Liptak, “Justices 5–4, Reject Corporate Spending Limit,” New York Times, January 21, 2010. ↵

- Campaign finance data for the 2008 campaign are available at the Federal Election Commission, “Presidential Campaign Finance: Contributions to All Candidates by State.” ↵

- Campaign Finance Institute, “Non-Party Spending Doubled in 2010 But Did Not Dictate the Results” press release, November 5, 2010. ↵

- Costas Panagopoulos, ed., Rewiring Politics: Presidential Nominating Conventions in the Media Age (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007). ↵