Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- Who makes up the Senate leadership?

- What roles do the presiding officer, floor leaders, and whips play in the Senate?

- What criteria do House members use when selecting their leadership?

- What roles do the Speaker, floor leaders, and whips play in the House?

The Senate leadership structure is similar to that in the House. The smaller chamber lacks the extensive formal rules of the House and thus requires its leaders to use their political and personal relations skills to move legislation through the institution.

The House leadership consists of the Speaker, floor leaders, and whips. Committee chairs also are part of the House leadership. The rules of the House give extensive power to leaders to direct the legislative process.

Leadership Criteria

House members consider a number of factors when choosing leaders. A member’s personal reputation, interactions with other members, legislative skills, expertise, experience, length of service, and knowledge of the institution are taken into account. Members tend to choose leaders who are in the ideological mainstream of their party and represent diverse regions of the country. The positions that a member has held in Congress, such as service on important committees, are evaluated. Fundraising ability, media prowess, and communications skills are increasingly important criteria for leadership. The ability to forge winning coalitions and the connections that a member has to leaders in the Senate or the executive branch are factored into the decision.[1]

Holding a congressional leadership position is challenging, especially as most members think of themselves as leaders rather than followers. Revolts can occur when members feel leaders are wielding too much power or promoting personal agendas at the expense of institutional goals. At times, a leader’s style or personality may rub members the wrong way and contribute to their being ousted from office.[2]

House of Representatives:

Speaker of the House

The Speaker of the House is at the top of the leadership hierarchy. The Speaker is second in succession to the presidency and is the only officer of the House mentioned specifically in the Constitution. The Speaker’s official duties include referring bills to committees, appointing members to select and conference committees, counting and announcing all votes on legislation, and signing all bills passed by the House. He rarely participates in floor debates or votes on bills. The Speaker also is the leader of his or her political party in the House. In this capacity, the Speaker oversees the party’s committee assignments, sets the agenda of activities in the House, and bestows rewards on faithful party members, such as committee leadership positions.[3]

In addition to these formal responsibilities, the Speaker has significant power to control the legislative agenda in the House. The Rules Committee, through which all bills must pass, functions as an arm of the Speaker. The Speaker appoints members of the Rules Committee who can be relied on to do his or her bidding. He or she exercises control over which bills make it to the floor for consideration and the procedures that will be followed during debate. Special rules, such as setting limits on amendments or establishing complex time allocations for debate, can influence the contents of a bill and help or hinder its passage.[4]

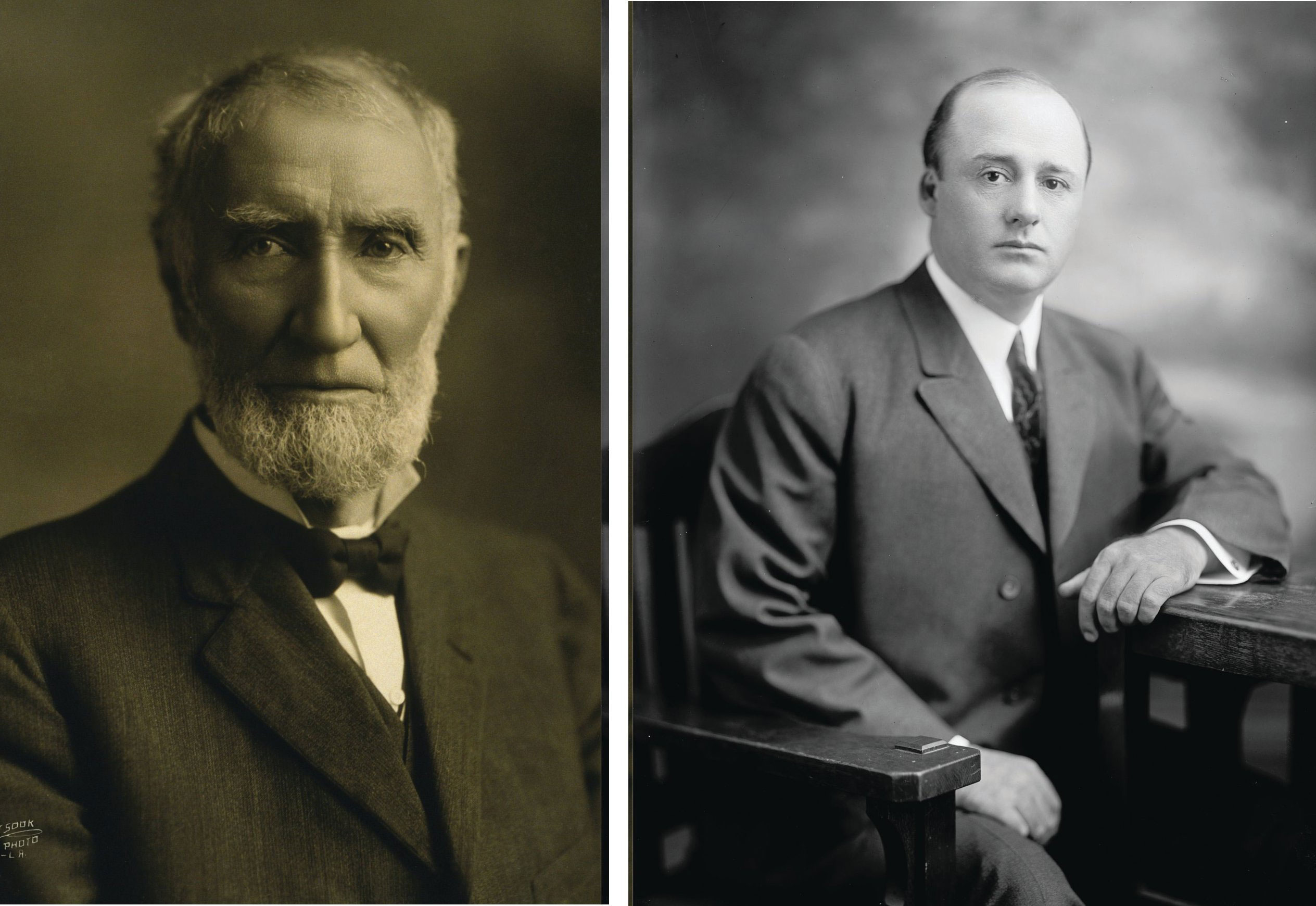

Speakers’ personal styles have influenced the evolution of the position. Speaker Joe Cannon (R-IL) became the most powerful Speaker of the House by using strong-arm tactics to control members of both parties. “Czar” Cannon’s style so angered his colleagues that he was forced to step down as chairman of the Rules Committee during the St. Patrick’s Day Revolt of 1910, which stripped him of his ability to control appointments and legislation. The position lost prestige and power until Speaker Sam Rayburn (D-TX) took office in 1940. Rayburn was able to use his popularity and political acumen to reestablish the Speakership as a powerful position.[5]

Strong Speakers of the House, such as Joe Cannon (left) and Sam Rayburn (right), were able to exert influence over other members. Strong speakers are no longer prominent in the House.

A Speaker’s personal style can influence the amount of media coverage the position commands. The Speaker can become the public face of the House by appearing frequently in the press. A charismatic speaker can rival the president in grabbing media attention and setting the nation’s issue agenda. On April 7, 1995, Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-GA) made an unprecedented prime-time television “State of the Congress” address on CBS indicating that the House has passed the Contract With America, a plan that proposed extensive changes to the social welfare system and tax policy. Despite the fact that the Contract with America died in the Senate, Gingrich became a “multimedia Whirling Dervish of books, writings, lectures, tapes, and television, spewing out ideas.”[6] He was a constant presence on the television and radio talk show circuit, which kept attention focused on his party’s issue platform. This strategy worked at the outset, as the Republicans were able to push through some of their proposals. Gingrich’s aggressive personal style and media blitz eventually backfired by alienating members of both parties. This experience illustrates that the media can have a boomerang effect—publicity can make a political leader and just as quickly can bring him down.

In contrast, Speaker Dennis Hastert (R-IL), who took office in 1999, exhibited an accommodating leadership style and was considered a “nice guy” by most members. He worked behind the scenes to build coalitions and achieve his policy initiatives. After the election of President George W. Bush, Hastert coordinated a communications strategy with the executive branch to promote a Republican policy agenda. He shared the media spotlight, which other members appreciated. His cooperative approach was effective in getting important budget legislation passed.[7]

Republican John Boehner of Ohio became Speaker of the House after the Republicans took control following the 2010 elections. He replaced Democrat Nancy Pelosi, the first woman Speaker.

Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) was the first woman Speaker of the House, serving from 2006 to 2010. Media coverage of Pelosi frequently included references to her gender, clothing, emotions, and personal style. Pelosi’s choice of Armani suits was much noted in the press following her selection. Syndicated New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd wrote a piece on November 6, 2006, titled “Squeaker of the House.” Dowd alleged that Pelosi’s first act after becoming Speaker was to “throw like a girl” and that she was “making her first move based on relationships and past slights rather than strategy.” “Squeaker of the House” became a moniker that stuck with Pelosi throughout her tenure as Speaker and was the subject of a YouTube parody. Pelosi was replaced by Rep. John Boehner (R-OH) when the Republicans took control of the House following the 2010 midterm elections. Boehner resigned as Speaker of the House and his congressional seat on October 29th 2015 and was replaced by Paul Ryan of Wisconsin.

Floor Leaders

The Republicans and Democrats elect floor leaders who coordinate legislative initiatives and serve as the chief spokespersons for their parties on the House floor. These positions are held by experienced legislators who have earned the respect of their colleagues. Floor leaders actively work at attracting media coverage to promote their party’s agenda. The leadership offices all have their own press secretaries.

The House majority leader is second to the Speaker in the majority party hierarchy. Working with the Speaker, he is responsible for setting the annual legislative agenda, scheduling legislation for consideration, and coordinating committee activity. He operates behind the scenes to ensure that the party gets the votes it needs to pass legislation. He consults with members and urges them to support the majority party and works with congressional leaders and the president, when the two are of the same party, to build coalitions. The majority leader monitors the floor carefully when bills are debated to keep his party members abreast of any key developments.[8]

Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) became House Majority Leader following Eric Cantor’s primary defeat in June 2014.

See House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s web page

The House minority leader is the party with the fewest members’ nominee for Speaker. She is the head of her party in the House and receives significant media coverage. She articulates the minority party’s policies and rallies members to court the media and publicly take on the policies of the majority party. She devises tactics that will place the minority party in the best position for influencing legislation by developing alternatives to legislative proposals supported by the majority. During periods of divided government, when the president is a member of the minority party, the minority leader serves as the president’s chief spokesperson in the House.[9]

Rep. Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) became House Minority Leader after she was replaced as Speaker of the House by Republican Rep. John Boehner (R-OH) following the 2010 midterm elections. Pelosi’s website does not mention her status as minority leader.

Whips

Members of Congress from the Republican and Democratic parties elect whips who are responsible for encouraging party loyalty and discipline in the House. Aided by extensive networks of deputies and assistants, whips make sure that the lines of communication between leaders and members remain open. In 2002, whip Steny Hoyer (D-MD) greatly expanded his organization to include forty senior whips and thirty assistant whips to enforce a “strategy of inclusion,” which gives more members the opportunity to work closely with party leaders and become vested in party decisions. This strategy made more party leaders with expertise available to the press in the hopes of increasing coverage of the Democratic Party’s positions. Whips keep track of members’ voting intentions on key bills and try persuade wayward members to toe the party line.[10]

Senate:

Presiding Officer

The presiding officer convenes floor action in the Senate. Unlike the Speaker of the House, the Senate’s presiding officer is not the most visible or powerful member. The Senate majority leader has this distinction.

The Constitution designates the vice president as president of the Senate, although he rarely presides and can vote only to break a tie. Republican senators made sure that Vice President Dick Cheney was on hand for close votes during the 107th Congress, when the number of Democrats and Republican Senators was nearly equal.

In the absence of the vice president, the Constitution provides for the president pro tempore to preside. The president pro tempore is the second-highest ranking member of the Senate behind the vice president. By convention, the president pro tempore is the majority party senator with the longest continuous service. The president pro tempore shares presiding officer duties with a handful of junior senators from both parties, who take half-hour shifts in the position.

Floor Leaders

The Senate majority leader, who is elected by the majority party, is the most influential member of the Senate. He is responsible for managing the business of the Senate by setting the schedule and overseeing floor activity. He is entitled to the right of first recognition, whereby the presiding officer allows him to speak on the floor before other senators. This right gives him a strategic advantage when trying to pass or defeat legislation, as he can seek to limit debate and amendments.

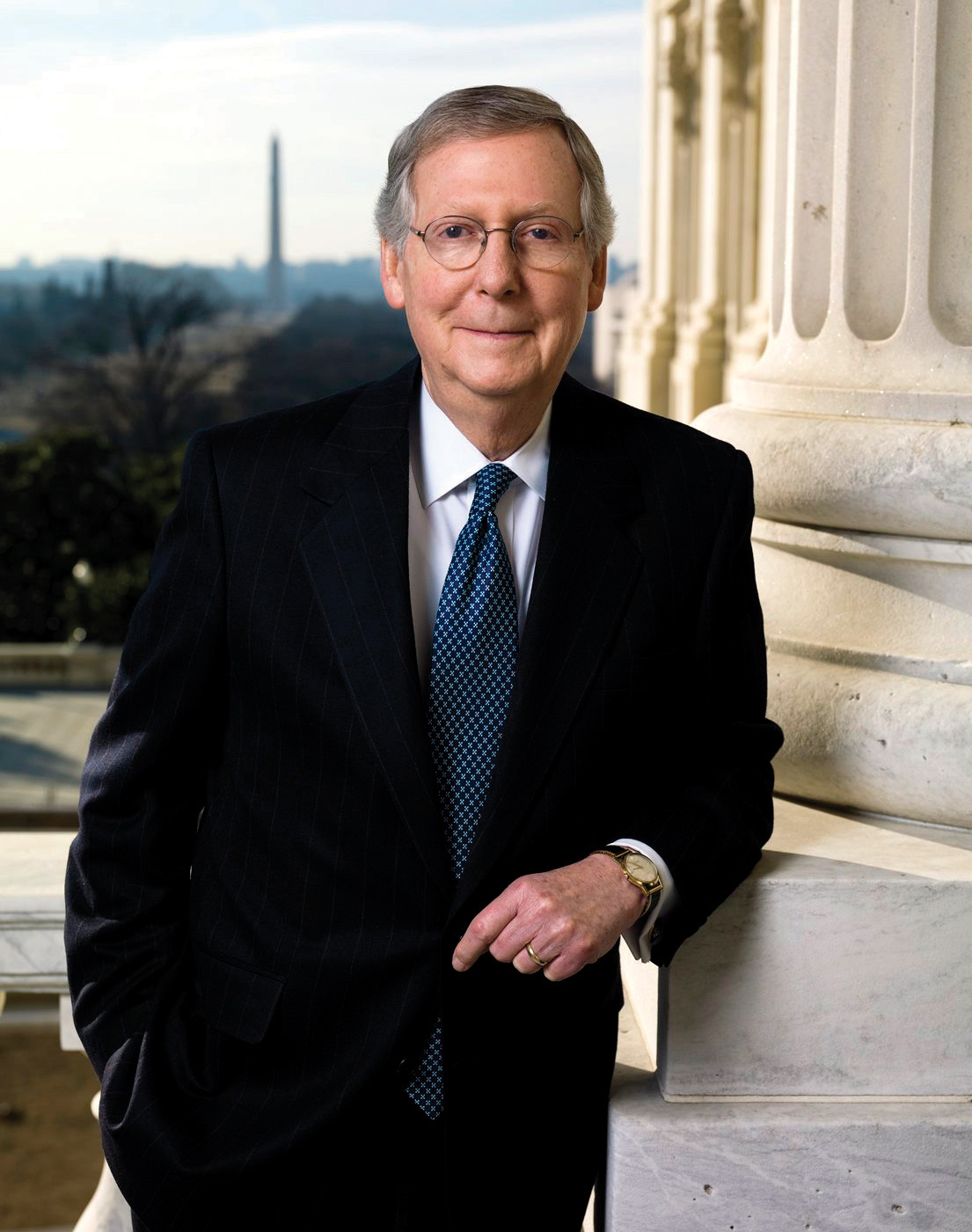

Senator Mitch McConnell, a Republican from Kentucky, is the Senate majority leader

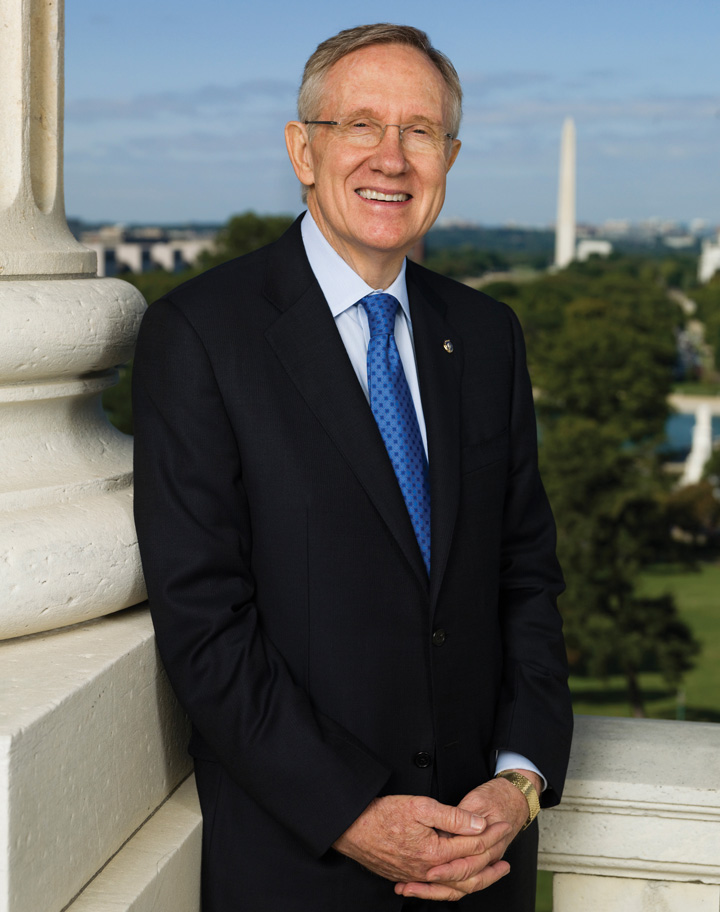

The Senate minority leader is the head of the opposing party. He works closely with the majority leader on scheduling. He confers regularly with members of his party to develop tactics for promoting their interests in the Senate.

Whips

Senate whips (assistant floor leaders) are referred to as assistant floor leaders, as they fill in when the majority and minority leaders are absent from the floor. Like their House counterparts, Senate whips are charged with devising a party strategy for passing legislation, keeping their party unified on votes, and building coalitions. The Senate whip network is not as extensive as its House counterpart. The greater intimacy of relationships in the Senate makes it easier for floor leaders to know how members will vote without relying on whip counts.

Candela Citations

- 21st Century American Government. Authored by: Anonymous. Provided by: Lardbucket. Located at: http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/21st-century-american-government-and-politics/s16-05-senate-leadership.html. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Mitch McConnell photo. Provided by: U.S. Senate. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sen_Mitch_McConnell_official.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Harry Reid portrait. Provided by: U.S. Congress. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harry_Reid_official_portrait_2009.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Robert L. Peabody, Leadership in Congress (Boston: Little, Brown, 1976). ↵

- Joseph Cooper and David W. Brady, “Institutional Context and Leadership Style: The House from Cannon to Rayburn,” American Political Science Review 75, no. 2 (June 1981): 411–25. ↵

- Thomas P. Carr, “Party Leaders in the House: Election, Duties, and Responsibilities,” CRS Report for Congress, October 5, 2001, order code RS20881. ↵

- Nicol C. Rae and Colton C. Campbell, eds. New Majority or Old Minority? (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1999). ↵

- Ronald M. Peters, Jr., The American Speakership (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997). ↵

- Dan Balz and Ronald Brownstein, Storming the Gates (Boston: Little Brown, 1996), 143. ↵

- Roger H. Davidson and Walter J. Oleszek, Congress and Its Members, 8th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2002). ↵

- Richard C. Sachs, “Leadership in the U.S. House of Representatives,” CRS Report for Congress, September 19, 1996, order code 96-784GOV. ↵

- Thomas P. Carr, “Party Leaders in the House: Election, Duties, and Responsibilities,” CRS Report for Congress, October 5, 2001, order code RS20881. ↵

- Roger H. Davidson and Walter J. Oleszek, Congress and Its Members, 8th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2002). ↵