Learning Objectives

- Multiply and divide radical expressions

- Use properties of exponents to multiply and divide radical expressions

- Add and subtract radical expressions

- Identify radicals that can be added or subtracted

- Add radical expressions

- Subtract radical expressions

- Rationalize denominators

- Define irrational and rational denominators

- Remove radicals from a single term denominator

Multiply and Divide

You can do more than just simplify radical expressions. You can multiply and divide them, too. Multiplying radicals is very simple if the index on all the radicals match. The prodcut rule of radicals can be generalized as follows

A Product Raised to a Power Rule

For any numbers a and b and any integer x: [latex] {{(ab)}^{x}}={{a}^{x}}\cdot {{b}^{x}}[/latex]

For any numbers a and b and any positive integer x: [latex] {{(ab)}^{\frac{1}{x}}}={{a}^{\frac{1}{x}}}\cdot {{b}^{\frac{1}{x}}}[/latex]

For any numbers a and b and any positive integer x: [latex] \sqrt[x]{ab}=\sqrt[x]{a}\cdot \sqrt[x]{b}[/latex]

The Product Raised to a Power Rule is important because you can use it to multiply radical expressions. Note that the roots are the same—you can combine square roots with square roots, or cube roots with cube roots, for example. But you can’t multiply a square root and a cube root using this rule.

In the following example, we multiply two square roots

Example

Simplify. [latex] \sqrt{18}\cdot \sqrt{16}[/latex]

Using the Product Raised to a Power Rule, you can take a seemingly complicated expression, [latex] \sqrt{18}\cdot \sqrt{16}[/latex], and turn it into something more manageable, [latex] 12\sqrt{2}[/latex].

You may have also noticed that both [latex] \sqrt{18}[/latex] and [latex] \sqrt{16}[/latex] can be written as products involving perfect square factors. How would the expression change if you simplified each radical first, before multiplying?

Example

Simplify. [latex] \sqrt{18}\cdot \sqrt{16}[/latex]

In both cases, you arrive at the same product, [latex] 12\sqrt{2}[/latex]. It does not matter whether you multiply the radicands or simplify each radical first.

You multiply radical expressions that contain variables in the same manner. As long as the roots of the radical expressions are the same, you can use the Product Raised to a Power Rule to multiply and simplify. Look at the two examples that follow. In both problems, the Product Raised to a Power Rule is used right away and then the expression is simplified.

Example

Simplify. [latex] \sqrt{12{{x}^{3}}}\cdot \sqrt{3x}[/latex], [latex] x\ge 0[/latex]

In this video example, we multiply more square roots with and without variables.

Example

Multiply [latex]2\sqrt[3]{18}\cdot-7\sqrt[3]{15}[/latex]

We will show one more example of multiplying cube root radicals, this time we will include a variable.

Example

Multiply [latex]\sqrt[3]{4x^3}\cdot\sqrt[3]{2x^2}[/latex]

In the next video, we present more examples of multiplying cube roots.

Dividing Radical Expressions

You can use the same ideas to help you figure out how to simplify and divide radical expressions. Recall that the Product Raised to a Power Rule states that [latex] \sqrt[x]{ab}=\sqrt[x]{a}\cdot \sqrt[x]{b}[/latex]. Well, what if you are dealing with a quotient instead of a product?

There is a rule for that, too. The Quotient Raised to a Power Rule states that [latex] {{\left( \frac{a}{b} \right)}^{x}}=\frac{{{a}^{x}}}{{{b}^{x}}}[/latex]. Again, if you imagine that the exponent is a rational number, then you can make this rule applicable for roots as well:

[latex] {{\left( \frac{a}{b} \right)}^{\frac{1}{x}}}=\frac{{{a}^{\frac{1}{x}}}}{{{b}^{\frac{1}{x}}}}[/latex]

Therefore

[latex] \sqrt[x]{\frac{a}{b}}=\frac{\sqrt[x]{a}}{\sqrt[x]{b}}[/latex].

A Quotient Raised to a Power Rule

For any real numbers a and b (b ≠ 0) and any positive integer x: [latex] {{\left( \frac{a}{b} \right)}^{\frac{1}{x}}}=\frac{{{a}^{\frac{1}{x}}}}{{{b}^{\frac{1}{x}}}}[/latex]

For any real numbers a and b (b ≠ 0) and any positive integer x: [latex] \sqrt[x]{\frac{a}{b}}=\frac{\sqrt[x]{a}}{\sqrt[x]{b}}[/latex]

As you did with multiplication, you will start with some examples featuring integers before moving on to radicals with variables.

Example

Simplify. [latex] \sqrt{\frac{48}{25}}[/latex]

As with multiplication, the main idea here is that sometimes it makes sense to divide and then simplify, and other times it makes sense to simplify and then divide. Whichever order you choose, though, you should arrive at the same final expression.

Now let’s turn to some radical expressions containing variables. Notice that the process for dividing these is the same as it is for dividing integers.

Example

Simplify. [latex]\frac{\sqrt{30x}}{\sqrt{10x}},x>0[/latex]

As you become more familiar with dividing and simplifying radical expressions, make sure you continue to pay attention to the roots of the radicals that you are dividing. For example, you can think of this expression:

[latex] \frac{\sqrt{8{{y}^{2}}}}{\sqrt{225{{y}^{4}}}}[/latex]

As equivalent to:

[latex] \sqrt{\frac{8{{y}^{2}}}{225{{y}^{4}}}}[/latex]

This is because both the numerator and the denominator are square roots.

Notice that you cannot express this expression:

[latex] \frac{\sqrt{8{{y}^{2}}}}{\sqrt[4]{225{{y}^{4}}}}[/latex]

In this format:

[latex] \sqrt[4]{\frac{8{{y}^{2}}}{225{{y}^{4}}}}[/latex].

This is becuase the numerator is a square root and the denominator is a fourth root. In this last video, we show more examples of simplifying a quotient with radicals.

Add and Subtract Radical Expressions

Adding and subtracting radicals is much like combining like terms with variables. We can add and subtract expressions with variables like this:

[latex]5x+3y - 4x+7y=x+10y[/latex]

There are two keys to combining radicals by addition or subtraction: look at the index, and look at the radicand. If these are the same, then addition and subtraction are possible. If not, then you cannot combine the two radicals.

Keys

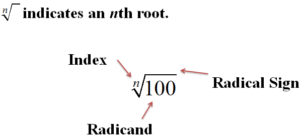

Remember the index is the degree of the root and the radicand is the term or expression under the radical. In the diagram below, the index is n, and the radicand is 100. The radicand is placed under the root symbol and the index is placed outside the root symbol to the left:

Index and radicand

Practice identifying radicals that are compatible for addition and subtraction by looking at the index and radicand of the roots in the following example.

Example

Identify the roots that have the same index and radicand.

[latex] 10\sqrt{6}[/latex]

[latex] -1\sqrt[3]{6}[/latex]

[latex] \sqrt{25}[/latex]

[latex] 12\sqrt{6}[/latex]

[latex] \frac{1}{2}\sqrt[3]{25}[/latex]

[latex] -7\sqrt[3]{6}[/latex]

Let’s use this concept to add some radicals.

Example

Add. [latex] 3\sqrt{11}+7\sqrt{11}[/latex]

It may help to think of radical terms with words when you are adding and subtracting them. The last example could be read “three square roots of eleven plus 7 square roots of eleven”.

This next example contains more addends. Notice how you can combine like terms (radicals that have the same root and index) but you cannot combine unlike terms.

Example

Add. [latex] 5\sqrt{2}+\sqrt{3}+4\sqrt{3}+2\sqrt{2}[/latex]

Notice that the expression in the previous example is simplified even though it has two terms: [latex] 7\sqrt{2}[/latex] and [latex] 5\sqrt{3}[/latex]. It would be a mistake to try to combine them further! (Some people make the mistake that [latex] 7\sqrt{2}+5\sqrt{3}=12\sqrt{5}[/latex]. This is incorrect because[latex] \sqrt{2}[/latex] and [latex]\sqrt{3}[/latex] are not like radicals so they cannot be added.)

Example

Add. [latex] 3\sqrt{x}+12\sqrt[3]{xy}+\sqrt{x}[/latex]

Sometimes you may need to add and simplify the radical. If the radicals are different, try simplifying first—you may end up being able to combine the radicals at the end, as shown in these next two examples.

Example

Add and simplify. [latex] 2\sqrt[3]{40}+\sqrt[3]{135}[/latex]

Example

Add and simplify. [latex] x\sqrt[3]{x{{y}^{4}}}+y\sqrt[3]{{{x}^{4}}y}[/latex]

Subtracting Radicals

Subtraction of radicals follows the same set of rules and approaches as addition—the radicands and the indices (plural of index) must be the same for two (or more) radicals to be subtracted.

Example

Subtract. [latex] 5\sqrt{13}-3\sqrt{13}[/latex]

Example

Subtract. [latex] 4\sqrt[3]{5a}-\sqrt[3]{3a}-2\sqrt[3]{5a}[/latex]

In the video example that follows, we show more examples of how to add and subtract radicals that don’t need to be simplified beforehand.

The following video shows how to add and subtract radicals that can be simplified beforehand.

Rationalize Denominators

Although radicals follow the same rules that integers do, it is often difficult to figure out the value of an expression containing radicals. For example, you probably have a good sense of how much [latex] \frac{4}{8},\ 0.75[/latex] and [latex] \frac{6}{9}[/latex] are, but what about the quantities [latex] \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}[/latex] and [latex] \frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}[/latex]? These are much harder to visualize.

You can use a technique called rationalizing a denominator to eliminate the radical. The point of rationalizing a denominator is to make it easier to understand what the quantity really is by removing radicals from the denominators.

Recall that the numbers 5, [latex] \frac{1}{2}[/latex], and [latex] 0.75[/latex] are all known as rational numbers—they can each be expressed as a ratio of two integers ([latex] \frac{5}{1},\frac{1}{2}[/latex], and [latex] \frac{3}{4}[/latex] respectively). Some radicals are irrational numbers because they cannot be represented as a ratio of two integers. As a result, the point of rationalizing a denominator is to change the expression so that the denominator becomes a rational number.

Here are some examples of irrational and rational denominators.

|

Irrational |

Rational |

|

|---|---|---|

|

[latex] \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}[/latex] |

= |

[latex] \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}[/latex] |

|

[latex] \frac{2+\sqrt{3}}{\sqrt{3}}[/latex] |

= |

[latex] \frac{2\sqrt{3}+3}{3}[/latex] |

Now let’s examine how to get from irrational to rational denominators.

Let’s start with the fraction [latex] \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}[/latex]. Its denominator is [latex] \sqrt{2}[/latex], an irrational number. This makes it difficult to figure out what the value of [latex] \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}[/latex] is.

You can rename this fraction without changing its value, if you multiply it by 1. In this case, set 1 equal to [latex] \frac{\sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{2}}[/latex]. Watch what happens.

[latex] \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\cdot 1=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\cdot \frac{\sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{2}}=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{2\cdot 2}}=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{4}}=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}[/latex]

The denominator of the new fraction is no longer a radical (notice, however, that the numerator is).

So why choose to multiply [latex] \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}[/latex] by [latex] \frac{\sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{2}}[/latex]? You knew that the square root of a number times itself will be a whole number. In algebraic terms, this idea is represented by [latex] \sqrt{x}\cdot \sqrt{x}=x[/latex]. Look back to the denominators in the multiplication of [latex] \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\cdot 1[/latex]. Do you see where [latex] \sqrt{2}\cdot \sqrt{2}=\sqrt{4}=2[/latex]?

Here are some more examples. Notice how the value of the fraction is not changed at all—it is simply being multiplied by 1.

Example

Rationalize the denominator.

[latex] \frac{-6\sqrt{6}}{\sqrt{3}}[/latex]

In the video example that follows, we show more examples of how to rationalize a denominator with an integer radicand.

You can use the same method to rationalize denominators to simplify fractions with radicals that contain a variable. As long as you multiply the original expression by another name for 1, you can eliminate a radical in the denominator without changing the value of the expression itself.

Example

Rationalize the denominator.

[latex] \frac{\sqrt{2y}}{\sqrt{4x}},\text{ where }x\ne \text{0}[/latex]

Example

Rationalize the denominator and simplify.

[latex] \sqrt{\frac{100x}{11y}},\text{ where }y\ne \text{0}[/latex]

THE video that follows shows more examples of how to rationalize a denominator with a monomial radicand.

Summary

When you encounter a fraction that contains a radical in the denominator, you can eliminate the radical by using a process called rationalizing the denominator. To rationalize a denominator, you need to find a quantity that, when multiplied by the denominator, will create a rational number (no radical terms) in the denominator. When the denominator contains a single term, as in [latex] \frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}[/latex], multiplying the fraction by [latex] \frac{\sqrt{5}}{\sqrt{5}}[/latex] will remove the radical from the denominator.

Summary

The Product Raised to a Power Rule and the Quotient Raised to a Power Rule can be used to simplify radical expressions as long as the roots of the radicals are the same. The Product Rule states that the product of two or more numbers raised to a power is equal to the product of each number raised to the same power. The same is true of roots: [latex] \sqrt[x]{ab}=\sqrt[x]{a}\cdot \sqrt[x]{b}[/latex]. When dividing radical expressions, the rules governing quotients are similar: [latex] \sqrt[x]{\frac{a}{b}}=\frac{\sqrt[x]{a}}{\sqrt[x]{b}}[/latex].

Combining radicals is possible when the index and the radicand of two or more radicals are the same. Radicals with the same index and radicand are known as like radicals. It is often helpful to treat radicals just as you would treat variables: like radicals can be added and subtracted in the same way that like variables can be added and subtracted. Sometimes, you will need to simplify a radical expression before it is possible to add or subtract like terms.