Learning Objective

- Compare the subjective and objective entrapment defenses.

Historically, no legal limit was placed on the government’s ability to induce individuals to commit crimes. The Constitution does not expressly prohibit this governmental action. Currently, however, all states and the federal government provide the defense of entrapment. The entrapment defense is based on the government’s use of inappropriately persuasive tactics when apprehending criminals. Entrapment is generally a perfect affirmative statutory or common-law defense.

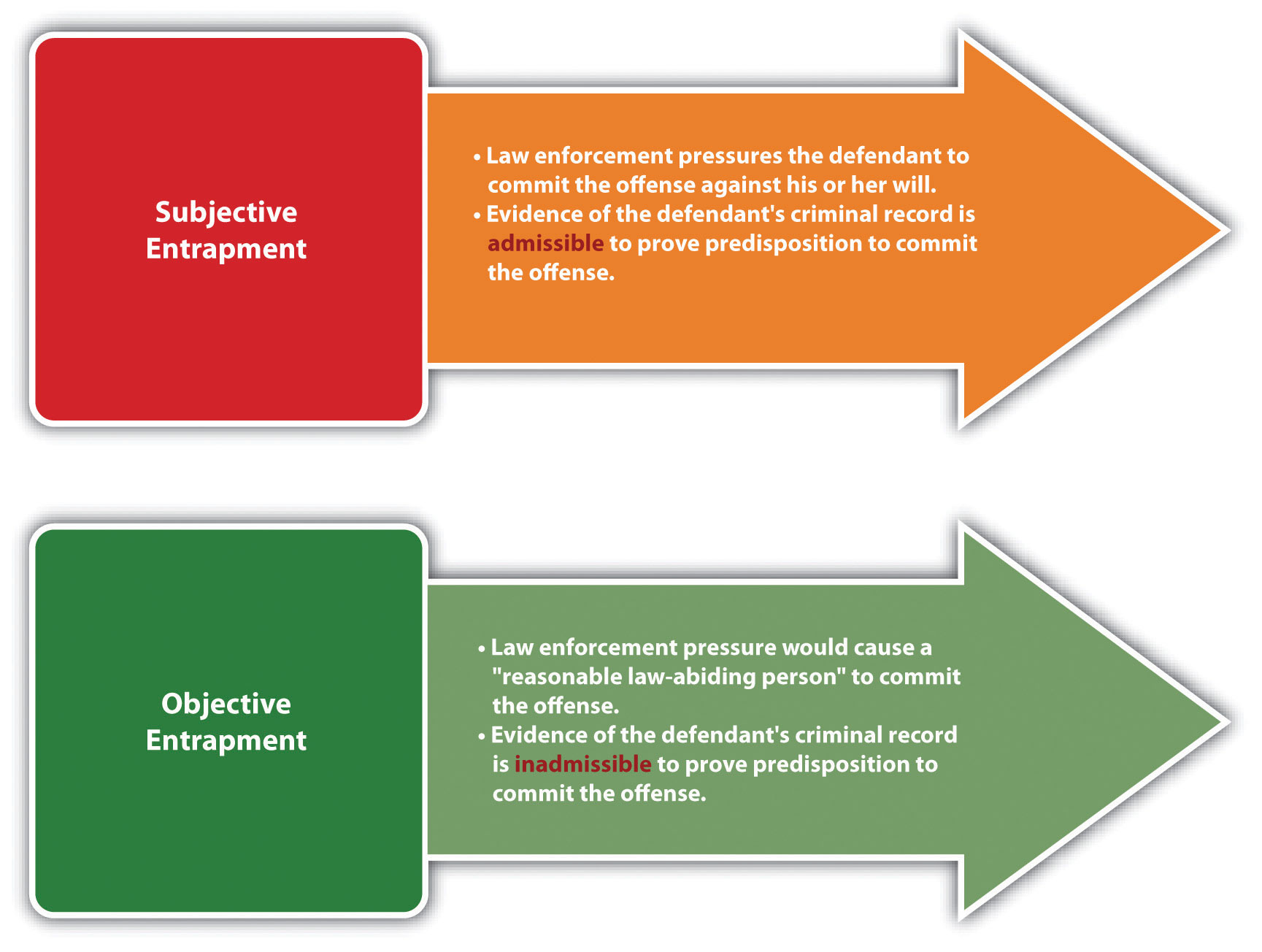

Entrapment focuses on the origin of criminal intent. If the criminal intent originates with the government or law enforcement, the defendant is entrapped and can assert the defense. If the criminal intent originates with the defendant, then the defendant is acting independently and can be convicted of the offense. The two tests of entrapment are subjective entrapment and objective entrapment. The federal government and the majority of the states recognize the subjective entrapment defense (Connecticut Jury Instruction on Entrapment, 2010). Other states and the Model Penal Code have adopted the objective entrapment defense (People v. Barraza, 2010).

Subjective Entrapment

It is entrapment pursuant to the subjective entrapment defense when law enforcement pressures the defendant to commit the crime against his or her will. The subjective entrapment test focuses on the defendant’s individual characteristics more than on law enforcement’s behavior. If the facts indicate that the defendant is predisposed to commit the crime without law enforcement pressure, the defendant will not prevail on the defense.

The defendant’s criminal record is admissible if relevant to prove the defendant’s criminal nature and predisposition. Generally, law enforcement can furnish criminal opportunities and use decoys and feigned accomplices without crossing the line into subjective entrapment. However, if it is clear that the requisite intent for the offense originated with law enforcement, not the defendant, the defendant can assert subjective entrapment as a defense.

Example of Subjective Entrapment

Winifred regularly attends Narcotics Anonymous (NA) for her heroin addiction. All the NA attendees know that Winifred is a dedicated member who has been clean for ten years, Marcus, a law enforcement decoy, meets Winifred at one of the meetings and begs her to “hook him up” with some heroin. Winifred refuses. Marcus attends the next meeting, and follows Winifred out to her car pleading with her to get him some heroin. After listening to Marcus explain his physical symptoms of withdrawal in detail, Winifred feels pity and promises to help Marcus out. She agrees to meet Marcus in two hours with the heroin. When Winifred and Marcus meet at the designated location, Marcus arrests Winifred for sale of narcotics. Winifred may be able to assert entrapment as a defense if her state recognizes the subjective entrapment defense. Winifred has not used drugs for ten years and did not initiate contact with law enforcement. It is unlikely that the intent to sell heroin originated with Winifred because she has been a dedicated member of NA, and she actually met Marcus at an NA meeting while trying to maintain her sobriety. Thus it appears that Marcus pressured Winifred to sell heroin against a natural predisposition, and the entrapment defense may excuse her conduct.

Objective Entrapment

The objective entrapment defense focuses on the behavior of law enforcement, rather than the individual defendant. If law enforcement uses tactics that would induce a reasonable, law-abiding person to commit the crime, the defendant can successfully assert the entrapment defense in an objective entrapment jurisdiction. The objective entrapment defense focuses on a reasonable person, not the actual defendant, so the defendant’s predisposition to commit the crime is not relevant. Thus in states that recognize the objective entrapment defense, the defendant’s criminal record is not admissible to disprove the defense.

Example of Objective Entrapment

Winifred has a criminal record for prostitution. A law enforcement decoy offers Winifred $10,000 to engage in sexual intercourse. Winifred promptly accepts. If Winifred’s jurisdiction recognizes the objective entrapment defense, Winifred may be able to successfully claim entrapment as a defense to prostitution. A reasonable, law-abiding person could be tempted into committing prostitution for a substantial sum of money like $10,000. The objective entrapment defense focuses on law enforcement tactics, rather than the predisposition of the defendant, so Winifred’s criminal record is irrelevant and is not admissible as evidence. Thus it appears that law enforcement used an excessive inducement, and entrapment may excuse Winifred’s conduct in this case.

Figure 6.9 Comparison of Subjective and Objective Entrapment

Figure 6.10 Diagram of Defenses, Part 2

Key Takeaway

- The subjective entrapment defense focuses on the individual defendant, and provides a defense if law enforcement pressures the defendant to commit the crime against his or her will. If the defendant is predisposed to commit the crime without this pressure, the defendant will not be successful with the defense. Pursuant to the subjective entrapment defense, the defendant’s criminal record is admissible to prove the defendant’s predisposition. The objective entrapment defense focuses on law enforcement behavior, and provides a defense if the tactics law enforcement uses would convince a reasonable, law-abiding person to commit the crime. Under the objective entrapment defense, the defendant’s criminal record is irrelevant and inadmissible.

Exercises

Answer the following questions. Check your answers using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

- Allen has a criminal record for burglary. Roger, a law enforcement decoy, approaches Allen and asks if he would like to purchase methamphetamine. Allen responds that he would and is arrested. This interaction takes place in a jurisdiction that recognizes the subjective entrapment defense. If Allen claims entrapment, will Allen’s criminal record be admissible to prove his predisposition to commit the crime at issue? Why or why not?

- Read Sosa v. Jones, 389 F.3d 644 (2004). In Jones, the US District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan denied the defendant’s petition for a writ of habeas corpus after he was sentenced to life in prison for conspiracy to sell and sale of cocaine. The defendant claimed he had been deprived of due process and was subjected to sentencing entrapment when federal agents delayed a sting operation to increase the amount of cocaine sold with the intent of increasing the defendant’s sentencing to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Did the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reverse the district court and grant the defendant’s petition? The case is available at this link: http://openjurist.org/389/f3d/644/sosa-v-jones.

- Read Farley v. State, 848 So.2d 393 (2003). In Farley, the government contacted the defendant, who had no criminal record, in a reverse sting operation with a mass e-mail soliciting individuals to purchase hard-core pornography. The defendant responded to the e-mail and was thereafter sent a questionnaire asking for his preferences. The defendant responded to the questionnaire, and an e-mail exchange ensued. In every communication by the government, protection from governmental interference was promised. Eventually, the defendant purchased child pornography and was arrested and prosecuted for this offense. The defendant moved to dismiss based on subjective and objective entrapment and the motion to dismiss was denied. The defendant was thereafter convicted. Did the Court of Appeal of Florida uphold the defendant’s conviction? The case is available at this link: http://www.lexisone.com/lx1/caselaw/freecaselaw?action=OCLGetCaseDetail&format=FULL&sourceID=bdjgjg&searchTerm= eiYL.TYda.aadj.ecCQ&searchFlag=y&l1loc=FCLOW.

References

Connecticut Jury Instruction on Entrapment, Based on Conn. Gen. Stats. Ann. § 53a-15, accessed December 10, 2010, http://www.jud.ct.gov/ji/criminal/part2/2.7-4.htm.

People v. Barraza, 591 P.2d 947 (1979), accessed December 10, 2010, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=4472828314482166952&hl=en&as_sdt=2&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr.

Candela Citations

- Criminal Law. Provided by: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing . Located at: http://open.lib.umn.edu/criminallaw/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike