Gustation (Taste)

Only a few recognized submodalities exist within the sense of taste, or gustation. Until recently, only four tastes were recognized: sweet, salty, sour, and bitter. Research at the turn of the 20th century led to recognition of the fifth taste, umami, during the mid-1980s. Umami is a Japanese word that means “delicious taste,” and is often translated to mean savory. Very recent research has suggested that there may also be a sixth taste for fats, or lipids.

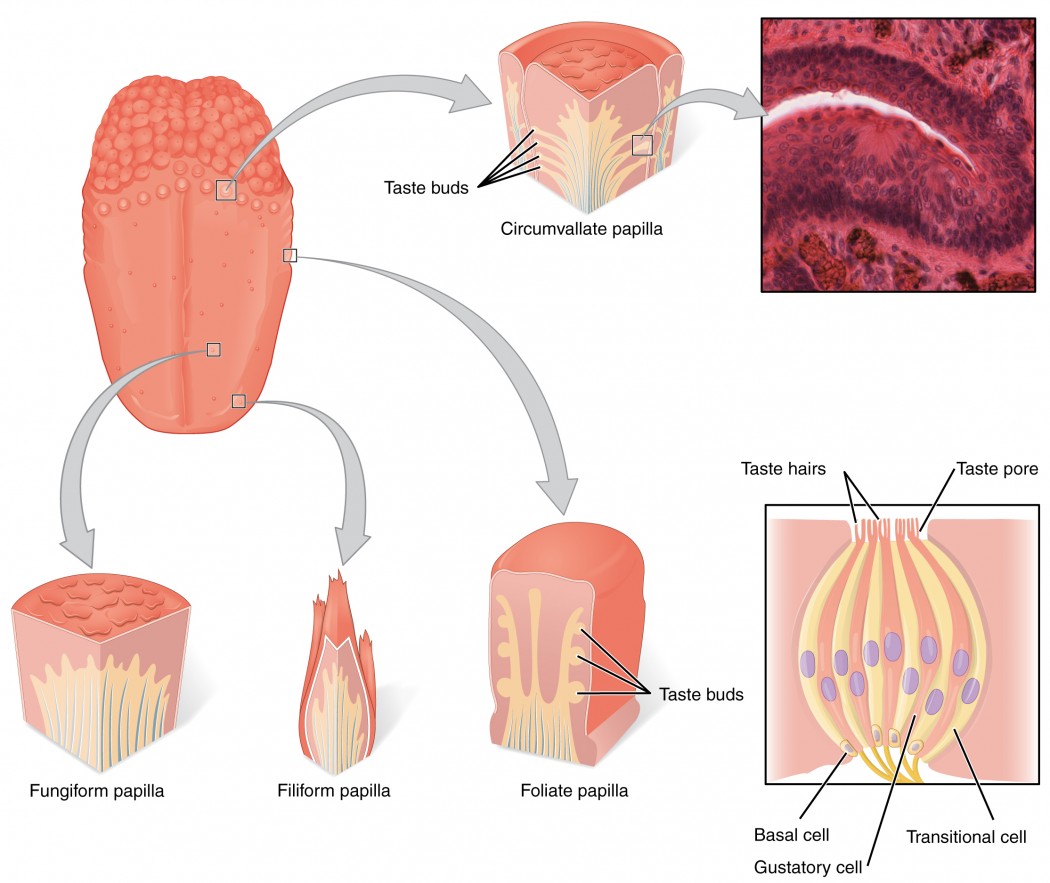

Gustation is the special sense associated with the tongue. The surface of the tongue, along with the rest of the oral cavity, is lined by a stratified squamous epithelium. Raised bumps called papillae (singular = papilla) contain the structures for gustatory transduction. There are four types of papillae, based on their appearance (Figure 2): circumvallate, foliate, filiform, and fungiform. Within the structure of the papillae are taste buds that contain specialized gustatory receptor cells for the transduction of taste stimuli. These receptor cells are sensitive to the chemicals contained within foods that are ingested, and they release neurotransmitters based on the amount of the chemical in the food. Neurotransmitters from the gustatory cells can activate sensory neurons in the facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagus cranial nerves.

Figure 2. The Tongue. The tongue is covered with small bumps, called papillae, which contain taste buds that are sensitive to chemicals in ingested food or drink. Different types of papillae are found in different regions of the tongue. The taste buds contain specialized gustatory receptor cells that respond to chemical stimuli dissolved in the saliva. These receptor cells activate sensory neurons that are part of the facial and glossopharyngeal nerves. LM × 1600. (Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

Salty taste is simply the perception of sodium ions (Na+) in the saliva. When you eat something salty, the salt crystals dissociate into the component ions Na+ and Cl–, which dissolve into the saliva in your mouth. The Na+ concentration becomes high outside the gustatory cells, creating a strong concentration gradient that drives the diffusion of the ion into the cells. The entry of Na+ into these cells results in the depolarization of the cell membrane and the generation of a receptor potential.

Sour taste is the perception of H+ concentration. Just as with sodium ions in salty flavors, these hydrogen ions enter the cell and trigger depolarization. Sour flavors are, essentially, the perception of acids in our food. Increasing hydrogen ion concentrations in the saliva (lowering saliva pH) triggers progressively stronger graded potentials in the gustatory cells. For example, orange juice—which contains citric acid—will taste sour because it has a pH value of approximately 3. Of course, it is often sweetened so that the sour taste is masked. The first two tastes (salty and sour) are triggered by the cations Na+ and H+. The other tastes result from food molecules binding to a G protein–coupled receptor. A G protein signal transduction system ultimately leads to depolarization of the gustatory cell.

The sweet taste is the sensitivity of gustatory cells to the presence of glucose dissolved in the saliva. Other monosaccharides such as fructose, or artificial sweeteners such as aspartame (NutraSweet™), saccharine, or sucralose (Splenda™) also activate the sweet receptors. The affinity for each of these molecules varies, and some will taste sweeter than glucose because they bind to the G protein–coupled receptor differently.

Bitter taste is similar to sweet in that food molecules bind to G protein–coupled receptors. However, there are a number of different ways in which this can happen because there are a large diversity of bitter-tasting molecules. Some bitter molecules depolarize gustatory cells, whereas others hyperpolarize gustatory cells. Likewise, some bitter molecules increase G protein activation within the gustatory cells, whereas other bitter molecules decrease G protein activation. The specific response depends on which molecule is binding to the receptor. One major group of bitter-tasting molecules are alkaloids. Alkaloids are nitrogen-containing molecules that often have a basic pH. Alkaloids are commonly found in bitter-tasting plant products, such as coffee, hops (in beer), tannins (in wine), tea, and aspirin. By containing toxic alkaloids, the plant is less susceptible to microbe infection and less attractive to herbivores. Therefore, the function of bitter taste may primarily be related to stimulating the gag reflex to avoid ingesting poisons. Because of this, many bitter foods that are normally ingested are often combined with a sweet component to make them more palatable (cream and sugar in coffee, for example). The highest concentration of bitter receptors appear to be in the posterior tongue, where a gag reflex could still spit out poisonous food.

The taste known as umami is often referred to as the savory taste. Like sweet and bitter, it is based on the activation of G protein–coupled receptors by a specific molecule. The molecule that activates this receptor is the amino acid L-glutamate. Therefore, the umami flavor is often perceived while eating protein-rich foods. Not surprisingly, dishes that contain meat are often described as savory.

Watch this video to learn about Dr. Danielle Reed of the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, who became interested in science at an early age because of her sensory experiences. She recognized that her sense of taste was unique compared with other people she knew. Now, she studies the genetic differences between people and their sensitivities to taste stimuli.

In the video, there is a brief image of a person sticking out their tongue, which has been covered with a colored dye. This is how Dr. Reed is able to visualize and count papillae on the surface of the tongue. People fall into two groups known as “tasters” and “non-tasters” based on the density of papillae on their tongue, which also indicates the number of taste buds. Non-tasters can taste food, but they are not as sensitive to certain tastes, such as bitterness. Dr. Reed discovered that she is a non-taster, which explains why she perceived bitterness differently than other people she knew. Are you very sensitive to tastes? Can you see any similarities among the members of your family?

Gustatory Nerve Impulses

Once the taste cells are activated by molecules liberated from the things we ingest, they release neurotransmitters onto the dendrites of sensory neurons. These neurons are part of the facial and glossopharyngeal cranial nerves, as well as a component within the vagus nerve dedicated to the gag reflex. The facial nerve connects to taste buds in the anterior third of the tongue. The glossopharyngeal nerve connects to taste buds in the posterior two thirds of the tongue. The vagus nerve connects to taste buds in the extreme posterior of the tongue, verging on the pharynx, which are more sensitive to noxious stimuli like bitterness.

Axons from the three cranial nerves carrying taste information travel to the medulla. From there much of the information is carried to the thalamus and then routed to the primary gustatory cortex, located near the inferior margin of the post-central gyrus. It is the primary gustatory cortex that is responsible for our sensations of taste. And, although this region receives significant input from taste buds, it is likely that it also receives information about the smell and texture of food, all contributing to our overall taste experience. The nuclei in the medulla also send projections to the hypothalamus and amygdala, which are involved in autonomic reflexes such as gagging and salivation.

Olfaction (Smell)

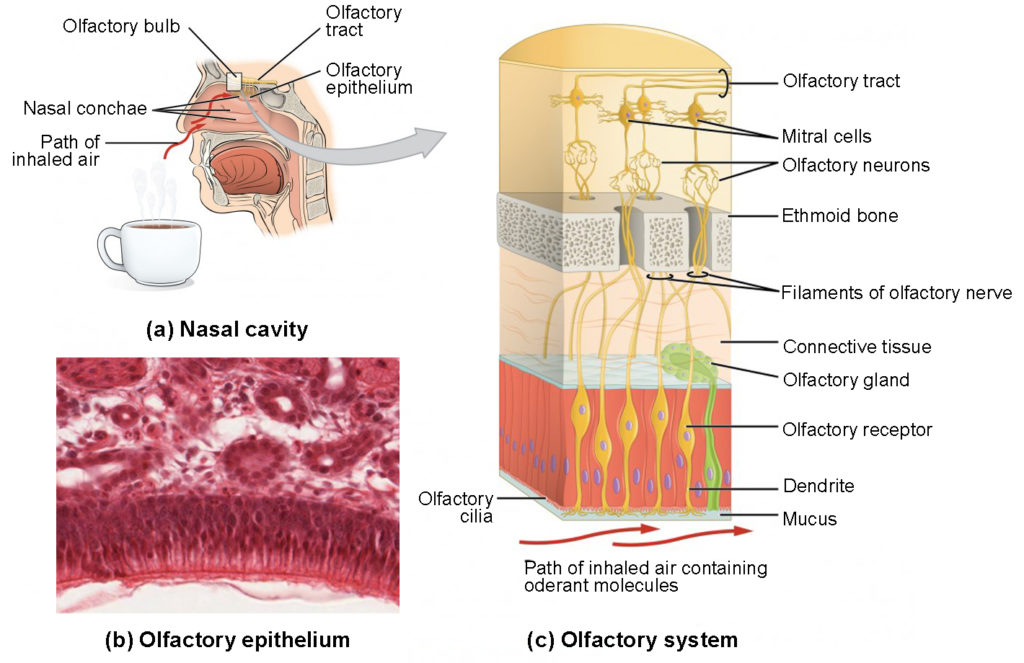

Like taste, the sense of smell, or olfaction, is also responsive to chemical stimuli. The olfactory receptor neurons are located in a small region within the superior nasal cavity (Figure 3). This region is referred to as the olfactory epithelium and contains bipolar sensory neurons. Each olfactory sensory neuron has dendrites that extend from the apical surface of the epithelium into the mucus lining the cavity. As airborne molecules are inhaled through the nose, they pass over the olfactory epithelial region and dissolve into the mucus. These odorant molecules bind to proteins that keep them dissolved in the mucus and help transport them to the olfactory dendrites. The odorant–protein complex binds to a receptor protein within the cell membrane of an olfactory dendrite. These receptors are G protein–coupled, and will produce a graded membrane potential in the olfactory neurons.

The axon of an olfactory neuron extends from the basal surface of the epithelium, through an olfactory foramen in the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone, and into the brain. The group of axons called the olfactory tract connect to the olfactory bulb on the ventral surface of the frontal lobe. From there, the axons split to travel to several brain regions. Some travel to the cerebrum, specifically to the primary olfactory cortex that is located in the inferior and medial areas of the temporal lobe. Others project to structures within the limbic system and hypothalamus, where smells become associated with long-term memory and emotional responses. This is how certain smells trigger emotional memories, such as the smell of food associated with one’s birthplace. Smell is the one sensory modality that does not synapse in the thalamus before connecting to the cerebral cortex. This intimate connection between the olfactory system and the cerebral cortex is one reason why smell can be a potent trigger of memories and emotion.

Figure 3. The Olfactory System (a) The olfactory system begins in the peripheral structures of the nasal cavity. (b) Axons of the olfactory receptor neurons project through the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone and synapse with the neurons of the olfactory bulb (tissue source: simian).LM × 812. (Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012) (c) The olfactory receptor neurons are within the olfactory epithelium.

The nasal epithelium, including the olfactory cells, can be harmed by airborne toxic chemicals. Therefore, the olfactory neurons are regularly replaced within the nasal epithelium, after which the axons of the new neurons must find their appropriate connections in the olfactory bulb. These new axons grow along the axons that are already in place in the cranial nerve.

Olfactory Nerve Impulses

The axons of the olfactory neurons extend from the basal surface of the epithelium, through an olfactory foramen in the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone, and into the olfactory bulb, located on the ventral surface of the frontal lobe. Collectively the axons that pass through the cribriform plate are called the olfactory nerve. From the olfactory bulb, axons project to structures within the limbic cortex, including the cortex in the temporal lobe associated with long-term memory formation.

Smell is the one sensory modality that does not require a synaptic connection in the thalamus before connecting to the cerebral cortex. Smell can often be a potent trigger for memories because of this intimate connection of the olfactory system with the cerebral cortex. It can also trigger visceral reflexes through connections within the reticular formation. For example, some people will vomit at the smell of another person’s vomit.

Disorders of the Olfactory System: Anosmia

Blunt force trauma to the face, such as that common in many car accidents, can lead to the loss of the olfactory nerve, and subsequently, loss of the sense of smell. This condition is known as anosmia. When the frontal lobe of the brain moves relative to the ethmoid bone, the olfactory tract axons may be sheared apart. Professional fighters often experience anosmia because of repeated trauma to face and head. In addition, certain pharmaceuticals, such as antibiotics, can cause anosmia by killing all the olfactory neurons at once. If no axons are in place within the olfactory nerve, then the axons from newly formed olfactory neurons have no guide to lead them to their connections within the olfactory bulb. There are temporary causes of anosmia, as well, such as those caused by inflammatory responses related to respiratory infections or allergies. Loss of the sense of smell can result in food tasting bland. A person with an impaired sense of smell may require additional spice and seasoning levels for food to be tasted. Anosmia may also be related to some presentations of mild depression, because the loss of enjoyment of food may lead to a general sense of despair. The ability of olfactory neurons to replace themselves decreases with age, leading to age-related anosmia. This explains why some elderly people salt their food more than younger people do. However, this increased sodium intake can increase blood volume and blood pressure, increasing the risk of cardiovascular diseases in the elderly.