The pelvic girdle (hip girdle) is formed by a single bone, the hip bone or coxal bone (coxal = “hip”), which serves as the attachment point for each lower limb. Each hip bone, in turn, is firmly joined to the axial skeleton via its attachment to the sacrum of the vertebral column. The right and left hip bones also converge anteriorly to attach to each other. The bony pelvis is the entire structure formed by the two hip bones, the sacrum, and, attached inferiorly to the sacrum, the coccyx (Figure 1).

Unlike the bones of the pectoral girdle, which are highly mobile to enhance the range of upper limb movements, the bones of the pelvis are strongly united to each other to form a largely immobile, weight-bearing structure. This is important for stability because it enables the weight of the body to be easily transferred laterally from the vertebral column, through the pelvic girdle and hip joints, and into either lower limb whenever the other limb is not bearing weight. Thus, the immobility of the pelvis provides a strong foundation for the upper body as it rests on top of the mobile lower limbs.

Figure 1. Pelvis. The pelvic girdle is formed by a single hip bone. The hip bone attaches the lower limb to the axial skeleton through its articulation with the sacrum. The right and left hip bones, plus the sacrum and the coccyx, together form the pelvis.

Hip Bone

The hip bone, or coxal bone, forms the pelvic girdle portion of the pelvis. The paired hip bones are the large, curved bones that form the lateral and anterior aspects of the pelvis. Each adult hip bone is formed by three separate bones that fuse together during the late teenage years. These bony components are the ilium, ischium, and pubis (Figure 2). These names are retained and used to define the three regions of the adult hip bone.

Figure 2. The Hip Bone. The adult hip bone consists of three regions. The ilium forms the large, fan-shaped superior portion, the ischium forms the posteroinferior portion, and the pubis forms the anteromedial portion.

The ilium is the fan-like, superior region that forms the largest part of the hip bone. It is firmly united to the sacrum at the largely immobile sacroiliac joint (see Figure 1). The ischium forms the posteroinferior region of each hip bone. It supports the body when sitting. The pubis forms the anterior portion of the hip bone. The pubis curves medially, where it joins to the pubis of the opposite hip bone at a specialized joint called the pubic symphysis.

Ilium

When you place your hands on your waist, you can feel the arching, superior margin of the ilium along your waistline (see Figure 2). This curved, superior margin of the ilium is the iliac crest. The rounded, anterior termination of the iliac crest is the anterior superior iliac spine. This important bony landmark can be felt at your anterolateral hip. Inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine is a rounded protuberance called the anterior inferior iliac spine. Both of these iliac spines serve as attachment points for muscles of the thigh. Posteriorly, the iliac crest curves downward to terminate as the posterior superior iliac spine. Muscles and ligaments surround but do not cover this bony landmark, thus sometimes producing a depression seen as a “dimple” located on the lower back. More inferiorly is the posterior inferior iliac spine. This is located at the inferior end of a large, roughened area called the auricular surface of the ilium. The auricular surface articulates with the auricular surface of the sacrum to form the sacroiliac joint. Both the posterior superior and posterior inferior iliac spines serve as attachment points for the muscles and very strong ligaments that support the sacroiliac joint.

The shallow depression located on the anteromedial (internal) surface of the upper ilium is called the iliac fossa. The inferior margin of this space is formed by the arcuate line of the ilium, the ridge formed by the pronounced change in curvature between the upper and lower portions of the ilium. The large, inverted U-shaped indentation located on the posterior margin of the lower ilium is called the greater sciatic notch.

Ischium

The ischium forms the posterolateral portion of the hip bone (see Figure 2). The large, roughened area of the inferior ischium is the ischial tuberosity. This serves as the attachment for the posterior thigh muscles and also carries the weight of the body when sitting. You can feel the ischial tuberosity if you wiggle your pelvis against the seat of a chair. Projecting superiorly and anteriorly from the ischial tuberosity is a narrow segment of bone called the ischial ramus. The slightly curved posterior margin of the ischium above the ischial tuberosity is the lesser sciatic notch. The bony projection separating the lesser sciatic notch and greater sciatic notch is the ischial spine.

Pubis

The pubis forms the anterior portion of the hip bone (see Figure 2). The enlarged medial portion of the pubis is the pubic body. Located superiorly on the pubic body is a small bump called the pubic tubercle. The superior pubic ramus is the segment of bone that passes laterally from the pubic body to join the ilium. The narrow ridge running along the superior margin of the superior pubic ramus is the pectineal line of the pubis.

The pubic body is joined to the pubic body of the opposite hip bone by the pubic symphysis. Extending downward and laterally from the body is the inferior pubic ramus. The pubic arch is the bony structure formed by the pubic symphysis, and the bodies and inferior pubic rami of the adjacent pubic bones. The inferior pubic ramus extends downward to join the ischial ramus. Together, these form the single ischiopubic ramus, which extends from the pubic body to the ischial tuberosity. The inverted V-shape formed as the ischiopubic rami from both sides come together at the pubic symphysis is called the subpubic angle.

Pelvis

The pelvis consists of four bones: the right and left hip bones, the sacrum, and the coccyx (see Figure 1). The pelvis has several important functions. Its primary role is to support the weight of the upper body when sitting and to transfer this weight to the lower limbs when standing. It serves as an attachment point for trunk and lower limb muscles, and also protects the internal pelvic organs. When standing in the anatomical position, the pelvis is tilted anteriorly. In this position, the anterior superior iliac spines and the pubic tubercles lie in the same vertical plane, and the anterior (internal) surface of the sacrum faces forward and downward.

The three areas of each hip bone, the ilium, pubis, and ischium, converge centrally to form a deep, cup-shaped cavity called the acetabulum. This is located on the lateral side of the hip bone and is part of the hip joint. The large opening in the anteroinferior hip bone between the ischium and pubis is the obturator foramen. This space is largely filled in by a layer of connective tissue and serves for the attachment of muscles on both its internal and external surfaces.

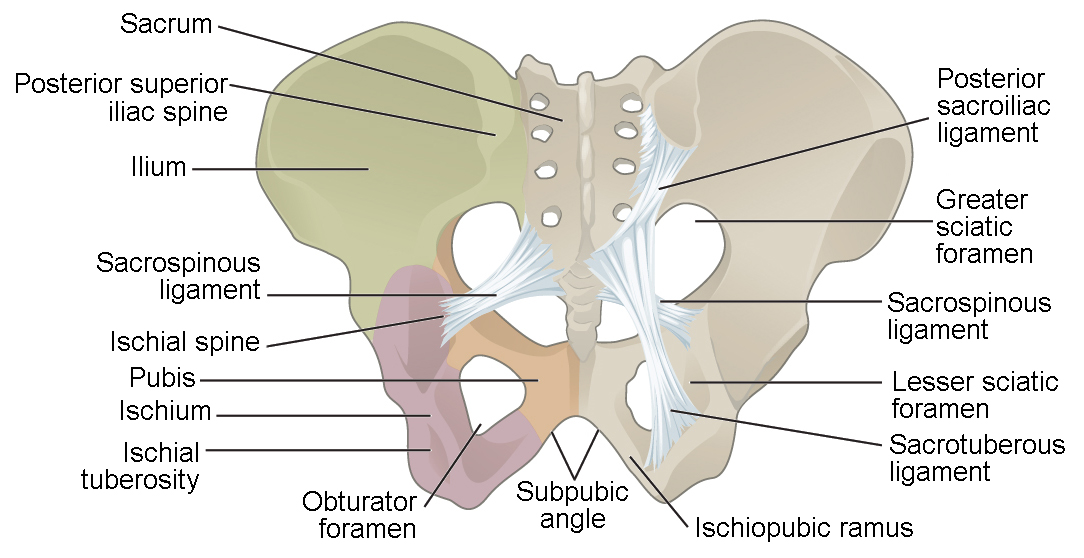

Several ligaments unite the bones of the pelvis (Figure 3). The largely immobile sacroiliac joint is supported by a pair of strong ligaments that are attached between the sacrum and ilium portions of the hip bone. These are the anterior sacroiliac ligament on the anterior side of the joint and the posterior sacroiliac ligament on the posterior side. Also spanning the sacrum and hip bone are two additional ligaments. The sacrospinous ligament runs from the sacrum to the ischial spine, and the sacrotuberous ligament runs from the sacrum to the ischial tuberosity. These ligaments help to support and immobilize the sacrum as it carries the weight of the body.

Figure 3. Ligaments of the Pelvis. The posterior sacroiliac ligament supports the sacroiliac joint. The sacrospinous ligament spans the sacrum to the ischial spine, and the sacrotuberous ligament spans the sacrum to the ischial tuberosity. The sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments contribute to the formation of the greater and lesser sciatic foramens.

Watch this video for a 3-D view of the pelvis and its associated ligaments. What is the large opening in the bony pelvis, located between the ischium and pubic regions, and what two parts of the pubis contribute to the formation of this opening?

The sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments also help to define two openings on the posterolateral sides of the pelvis through which muscles, nerves, and blood vessels for the lower limb exit. The superior opening is the greater sciatic foramen. This large opening is formed by the greater sciatic notch of the hip bone, the sacrum, and the sacrospinous ligament. The smaller, more inferior lesser sciatic foramen is formed by the lesser sciatic notch of the hip bone, together with the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments.

The space enclosed by the bony pelvis is divided into two regions (Figure 4). The broad, superior region, defined laterally by the large, fan-like portion of the upper hip bone, is called the greater pelvis (greater pelvic cavity; false pelvis). This broad area is occupied by portions of the small and large intestines, and because it is more closely associated with the abdominal cavity, it is sometimes referred to as the false pelvis. More inferiorly, the narrow, rounded space of the lesser pelvis (lesser pelvic cavity; true pelvis) contains the bladder and other pelvic organs, and thus is also known as the true pelvis. The pelvic brim (also known as the pelvic inlet) forms the superior margin of the lesser pelvis, separating it from the greater pelvis. The pelvic brim is defined by a line formed by the upper margin of the pubic symphysis anteriorly, and the pectineal line of the pubis, the arcuate line of the ilium, and the sacral promontory (the anterior margin of the superior sacrum) posteriorly. The inferior limit of the lesser pelvic cavity is called the pelvic outlet. This large opening is defined by the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis anteriorly, and the ischiopubic ramus, the ischial tuberosity, the sacrotuberous ligament, and the inferior tip of the coccyx posteriorly. Because of the anterior tilt of the pelvis, the lesser pelvis is also angled, giving it an anterosuperior (pelvic inlet) to posteroinferior (pelvic outlet) orientation.

Figure 4. Pelvis Variations. Those with Egg-producing and conducting (EPC) organs tend to have a pelvis that is broader, with a larger subpubic angle, a rounder pelvic brim, and a wider and more shallow lesser pelvic cavity than the pelvis of those with Sperm-producing and conducting (SPC) organs.

Variations in Pelvis Anatomy

There is a wide range of slight anatomical differences in the pelvis when looking at different individuals. At the most extreme ends of these variations are aspects associated with those who possess Egg-producing and conducting (EPC) organs compared to those who possess Sperm-producing and conducting (SPC) organs. In general, the bones of the pelvis are thicker and heavier in those who have SPC organs, which is adapted for support of the heavier physical build and larger muscles associated with higher levels of testosterone. In individuals with SPC organs, the greater sciatic notch of the hip bone is narrower and deeper than the broader notch of those with EPC organs. Those with EPC organs have a pelvis that is adapted for childbirth, which is wider as evidenced by the distance between the anterior superior iliac spines (see Figure 4). The ischial tuberosities of are also farther apart, which increases the size of the pelvic outlet for those with EPC organs. Because of this increased pelvic width, the subpubic angle is larger in those with EPC organs (greater than 80 degrees) than it is in those with SPC organs (less than 70 degrees). The sacrum is wider, shorter, and less curved, and the sacral promontory projects less into the pelvic cavity, thus giving the pelvic inlet (pelvic brim) a more rounded or oval shape in people with EPC organs compared to those with SPC organs. The lesser pelvic cavity is also wider and more shallow in those with EPC organs than the narrower, deeper, and tapering lesser pelvis of those with SPC organs. These are generalizations of some of the major pelvic differences that can be observed at the extreme ends of anatomical variations between those with EPC or SPC organs, with most individuals falling somewhere in between these sets of characteristics. Table 1 provides an overview of these general differences.

| Table 1. Overview of Differences in Pelvis Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| EPC organs pelvis | SPC organs pelvis | |

| Pelvic weight | Bones of the pelvis are lighter and thinner | Bones of the pelvis are thicker and heavier |

| Pelvic inlet shape | Pelvic inlet has a round or oval shape | Pelvic inlet is heart-shaped |

| Lesser pelvic cavity shape | Lesser pelvic cavity is shorter and wider | Lesser pelvic cavity is longer and narrower |

| Subpubic angle | Subpubic angle is greater than 80 degrees | Subpubic angle is less than 70 degrees |

| Pelvic outlet shape | Pelvic outlet is rounded and larger | Pelvic outlet is smaller |

Career Connection: Forensic Pathology and Forensic Anthropology

A forensic pathologist (also known as a medical examiner) is a medically trained physician who has been specifically trained in pathology to examine the bodies of the deceased to determine the cause of death. A forensic pathologist applies their understanding of disease as well as toxins, blood and DNA analysis, firearms and ballistics, and other factors to assess the cause and manner of death. At times, a forensic pathologist will be called to testify under oath in situations that involve a possible crime. Forensic pathology is a field that has received much media attention on television shows or following a high-profile death.

While forensic pathologists are responsible for determining whether the cause of someone’s death was natural, a suicide, accidental, or a homicide, there are times when uncovering the cause of death is more complex, and other skills are needed. Forensic anthropology brings the tools and knowledge of physical anthropology and human osteology (the study of the skeleton) to the task of investigating a death. A forensic anthropologist assists medical and legal professionals in identifying human remains. The science behind forensic anthropology involves the study of archaeological excavation; the examination of hair; an understanding of plants, insects, and footprints; the ability to determine how much time has elapsed since the person died; the analysis of past medical history and toxicology; the ability to determine whether there are any postmortem injuries or alterations of the skeleton; and the identification of the decedent (deceased person) using skeletal and dental evidence.

Due to the extensive knowledge and understanding of excavation techniques, a forensic anthropologist is an integral and invaluable team member to have on-site when investigating a crime scene, especially when the recovery of human skeletal remains is involved. When remains are bought to a forensic anthropologist for examination, they must first determine whether the remains are in fact human. Once the remains have been identified as belonging to a person and not to an animal, the next step is to approximate the individual’s age, sex, race, and height. The forensic anthropologist does not determine the cause of death, but rather provides information to the forensic pathologist, who will use all of the data collected to make a final determination regarding the cause of death.

Candela Citations

- Anatomy & Physiology. Authored by: OpenStax College. Provided by: Rice University. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/14fb4ad7-39a1-4eee-ab6e-3ef2482e3e22@9.1. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/14fb4ad7-39a1-4eee-ab6e-3ef2482e3e22@9.1