The term tissue is used to describe a group of cells found together in the body. The cells within a tissue share a common embryonic origin. Microscopic observation reveals that the cells in a tissue share morphological features and are arranged in an orderly pattern that achieves the tissue’s functions. From the evolutionary perspective, tissues appear in more complex organisms. For example, multicellular protists, ancient eukaryotes, do not have cells organized into tissues.

Although there are many types of cells in the human body, they are organized into four broad categories of tissues: epithelial, connective, muscle, and nervous. Each of these categories is characterized by specific functions that contribute to the overall health and maintenance of the body. A disruption of the structure is a sign of injury or disease. Such changes can be detected through histology, the microscopic study of tissue appearance, organization, and function.

The Four Types of Tissues

Epithelial tissue, also referred to as epithelium, refers to the sheets of cells that cover exterior surfaces of the body, lines internal cavities and passageways, and forms certain glands. Connective tissue, as its name implies, binds the cells and organs of the body together and functions in the protection, support, and integration of all parts of the body. Muscle tissue is excitable, responding to stimulation and contracting to provide movement, and occurs as three major types: skeletal (voluntary) muscle, smooth muscle, and cardiac muscle in the heart. Nervous tissue is also excitable, allowing the propagation of electrochemical signals in the form of nerve impulses that communicate between different regions of the body (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Four Types of Tissue: Body. The four types of tissues are exemplified in nervous tissue, stratified squamous epithelial tissue, cardiac muscle tissue, and connective tissue in small intestine. Clockwise from nervous tissue, LM × 872, LM × 282, LM × 460, LM × 800. (Micrographs provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

The next level of organization is the organ, where several types of tissues come together to form a working unit. Just as knowing the structure and function of cells helps you in your study of tissues, knowledge of tissues will help you understand how organs function. The epithelial and connective tissues are discussed in detail in this chapter. Muscle and nervous tissues will be discussed only briefly in this chapter.

Tissue Membranes

A tissue membrane is a thin layer or sheet of cells that covers the outside of the body (for example, skin), the organs (for example, pericardium), internal passageways that lead to the exterior of the body (for example, abdominal mesenteries), and the lining of the moveable joint cavities. There are two basic types of tissue membranes: connective tissue and epithelial membranes (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Tissue Membranes. The two broad categories of tissue membranes in the body are (1) connective tissue membranes, which include synovial membranes, and (2) epithelial membranes, which include mucous membranes, serous membranes, and the cutaneous membrane, in other words, the skin.

Epithelial Tissues

Epithelial tissues cover the outside of organs and structures in the body and line the lumens of organs in a single layer or multiple layers of cells. The types of epithelia are classified by the shapes of cells present and the number of layers of cells. Epithelia composed of a single layer of cells is called simple epithelia; epithelial tissue composed of multiple layers is called stratified epithelia. (Figure 4) summarizes the different types of epithelial tissues.

Figure 4. Cells of Epithelial Tissue. Simple epithelial tissue is organized as a single layer of cells and stratified epithelial tissue is formed by several layers of cells.

| Different Types of Epithelial Tissues | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cell shape | Description | Location |

| squamous | flat, irregular round shape | simple: lung alveoli, capillaries; stratified: skin, mouth, vagina |

| cuboidal | cube shaped, central nucleus | glands, renal tubules |

| columnar | tall, narrow, nucleus toward base; tall, narrow, nucleus along cell | simple: digestive tract; pseudostratified: respiratory tract |

| transitional | round, simple but appear stratified | urinary bladder |

Squamous Epithelia

Squamous epithelial cells are generally round, flat, and have a small, centrally located nucleus. The cell outline is slightly irregular, and cells fit together to form a covering or lining. When the cells are arranged in a single layer (simple epithelia), they facilitate diffusion in tissues, such as the areas of gas exchange in the lungs and the exchange of nutrients and waste at blood capillaries.

Figure 5. Squamous epithelia cells (a) have a slightly irregular shape, and a small, centrally located nucleus. These cells can be stratified into layers, as in (b) this human cervix specimen. (credit b: modification of work by Ed Uthman; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

(Figure 5)a illustrates a layer of squamous cells with their membranes joined together to form an epithelium. Image (Figure 5)b illustrates squamous epithelial cells arranged in stratified layers, where protection is needed on the body from outside abrasion and damage. This is called a stratified squamous epithelium and occurs in the skin and in tissues lining the mouth and vagina.

Cuboidal Epithelia

Cuboidal epithelial cells, shown in (Figure 6), are cube-shaped with a single, central nucleus. They are most commonly found in a single layer representing a simple epithelia in glandular tissues throughout the body where they prepare and secrete glandular material. They are also found in the walls of tubules and in the ducts of the kidney and liver.

Figure 6. Simple cuboidal epithelial cells line tubules in the mammalian kidney, where they are involved in filtering the blood.

Columnar Epithelia

Columnar epithelial cells are taller than they are wide: they resemble a stack of columns in an epithelial layer, and are most commonly found in a single-layer arrangement. The nuclei of columnar epithelial cells in the digestive tract appear to be lined up at the base of the cells, as illustrated in (Figure 7). These cells absorb material from the lumen of the digestive tract and prepare it for entry into the body through the circulatory and lymphatic systems.

Figure 7. Simple columnar epithelial cells absorb material from the digestive tract. Goblet cells secret mucous into the digestive tract lumen.

Columnar epithelial cells lining the respiratory tract appear to be stratified. However, each cell is attached to the base membrane of the tissue and, therefore, they are simple tissues. The nuclei are arranged at different levels in the layer of cells, making it appear as though there is more than one layer, as seen in (Figure 8). This is called pseudostratified, columnar epithelia. This cellular covering has cilia at the apical, or free, surface of the cells. The cilia enhance the movement of mucous and trapped particles out of the respiratory tract, helping to protect the system from invasive microorganisms and harmful material that has been breathed into the body. Goblet cells are interspersed in some tissues (such as the lining of the trachea). The goblet cells contain mucous that traps irritants, which in the case of the trachea keep these irritants from getting into the lungs.

Figure 8. Pseudostratified columnar epithelia line the respiratory tract. They exist in one layer, but the arrangement of nuclei at different levels makes it appear that there is more than one layer. Goblet cells interspersed between the columnar epithelial cells secrete mucous into the respiratory tract.

Connective Tissues

Connective tissues are made up of a matrix consisting of living cells and a nonliving substance, called the ground substance. The ground substance is made of an organic substance (usually a protein) and an inorganic substance (usually a mineral or water). The principal cell of connective tissues is the fibroblast. This cell makes the fibers found in nearly all of the connective tissues. Fibroblasts are motile, able to carry out mitosis, and can synthesize whichever connective tissue is needed. Macrophages, lymphocytes, and, occasionally, leukocytes can be found in some of the tissues. Some tissues have specialized cells that are not found in the others. The matrix in connective tissues gives the tissue its density. When a connective tissue has a high concentration of cells or fibers, it has proportionally a less dense matrix.

The organic portion or protein fibers found in connective tissues are either collagen, elastic, or reticular fibers. Collagen fibers provide strength to the tissue, preventing it from being torn or separated from the surrounding tissues. Elastic fibers are made of the protein elastin; this fiber can stretch to one and one half of its length and return to its original size and shape. Elastic fibers provide flexibility to the tissues. Reticular fibers are the third type of protein fiber found in connective tissues. This fiber consists of thin strands of collagen that form a network of fibers to support the tissue and other organs to which it is connected. The various types of connective tissues, the types of cells and fibers they are made of, and sample locations of the tissues is summarized in below.

| Connective Tissues | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | Cells | Fibers | Location |

| loose/areolar | fibroblasts, macrophages, some lymphocytes, some neutrophils | few: collagen, elastic, reticular | around blood vessels; anchors epithelia |

| dense, fibrous connective tissue | fibroblasts, macrophages | mostly collagen | irregular: skin; regular: tendons, ligaments |

| cartilage | chondrocytes, chondroblasts | hyaline: few: collagen fibrocartilage: large amount of collagen | shark skeleton, fetal bones, human ears, intervertebral discs |

| bone | osteoblasts, osteocytes, osteoclasts | some: collagen, elastic | vertebrate skeletons |

| adipose | adipocytes | few | adipose (fat) |

| blood | red blood cells, white blood cells | none | blood |

Loose/Areolar Connective Tissue

Loose connective tissue, also called areolar connective tissue, has a sampling of all of the components of a connective tissue. As illustrated in (Figure 9), loose connective tissue has some fibroblasts; macrophages are present as well. Collagen fibers are relatively wide and stain a light pink, while elastic fibers are thin and stain dark blue to black. The space between the formed elements of the tissue is filled with the matrix. The material in the connective tissue gives it a loose consistency similar to a cotton ball that has been pulled apart. Loose connective tissue is found around every blood vessel and helps to keep the vessel in place. The tissue is also found around and between most body organs. In summary, areolar tissue is tough, yet flexible, and comprises membranes.

Figure 9. Loose connective tissue is composed of loosely woven collagen and elastic fibers. The fibers and other components of the connective tissue matrix are secreted by fibroblasts.

Fibrous Connective Tissue

Fibrous connective tissues contain large amounts of collagen fibers and few cells or matrix material. The fibers can be arranged irregularly or regularly with the strands lined up in parallel. Irregularly arranged fibrous connective tissues are found in areas of the body where stress occurs from all directions, such as the dermis of the skin. Regular fibrous connective tissue, shown in (Figure 10), is found in tendons (which connect muscles to bones) and ligaments (which connect bones to bones).

Figure 10. Fibrous connective tissue from the tendon has strands of collagen fibers lined up in parallel.

Cartilage

Cartilage is a connective tissue with a large amount of the matrix and variable amounts of fibers. The cells, called chondrocytes, make the matrix and fibers of the tissue. Chondrocytes are found in spaces within the tissue called lacunae.

The three main types of cartilage tissue are hyaline cartilage, fibrocartilage, and elastic cartilage. Hyaline cartilage, the most common type of cartilage in the body, consists of short and dispersed collagen fibers and contains large amounts of proteoglycans. Under the microscope, tissue samples appear clear. The surface of hyaline cartilage is smooth. Both strong and flexible, it is found in the rib cage and nose and covers bones where they meet to form moveable joints. It makes up a template of the embryonic skeleton before bone formation. A plate of hyaline cartilage at the ends of bone allows continued growth until adulthood. Fibrocartilage is tough because it has thick bundles of collagen fibers dispersed through its matrix. The knee and jaw joints and the the intervertebral discs are examples of fibrocartilage. Elastic cartilage contains elastic fibers as well as collagen and proteoglycans. This tissue gives rigid support as well as elasticity. Tug gently at your ear lobes, and notice that the lobes return to their initial shape. The external ear contains elastic cartilage.

Figure 11. Types of Cartilage. Cartilage is a connective tissue consisting of collagenous fibers embedded in a firm matrix of chondroitin sulfates. (a) Hyaline cartilage provides support with some flexibility. The example is from dog tissue. (b) Fibrocartilage provides some compressibility and can absorb pressure. (c) Elastic cartilage provides firm but elastic support. From top, LM × 300, LM × 1200, LM × 1016. (Micrographs provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

Bone

Bone, or osseous tissue, is a connective tissue that has a large amount of two different types of matrix material. The organic matrix is similar to the matrix material found in other connective tissues, including some amount of collagen and elastic fibers. This gives strength and flexibility to the tissue. The inorganic matrix consists of mineral salts—mostly calcium salts—that give the tissue hardness. Without adequate organic material in the matrix, the tissue breaks; without adequate inorganic material in the matrix, the tissue bends.

There are three types of cells in bone: osteoblasts, osteocytes, and osteoclasts. Osteoblasts are active in making bone for growth and remodeling. Osteoblasts deposit bone material into the matrix and, after the matrix surrounds them, they continue to live, but in a reduced metabolic state as osteocytes. Osteocytes are found in lacunae of the bone. Osteoclasts are active in breaking down bone for bone remodeling, and they provide access to calcium stored in tissues. Osteoclasts are usually found on the surface of the tissue.

Bone can be divided into two types: compact and spongy. Compact bone is found in the shaft (or diaphysis) of a long bone and the surface of the flat bones, while spongy bone is found in the end (or epiphysis) of a long bone. Compact bone is organized into subunits called osteons, as illustrated in (Figure12). A blood vessel and a nerve are found in the center of the structure within the Haversian canal, with radiating circles of lacunae around it known as lamellae. The wavy lines seen between the lacunae are microchannels called canaliculi; they connect the lacunae to aid diffusion between the cells. Spongy bone is made of tiny plates called trabeculae; these plates serve as struts to give the spongy bone strength. Over time, these plates can break causing the bone to become less resilient. Bone tissue forms the internal skeleton of vertebrate animals, providing structure to the animal and points of attachment for tendons.

Figure 12. (a) Compact bone is a dense matrix on the outer surface of bone. Spongy bone, inside the compact bone, is porous with web-like trabeculae. (b) Compact bone is organized into rings called osteons. Blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels are found in the central Haversian canal. Rings of lamellae surround the Haversian canal. Between the lamellae are cavities called lacunae. Canaliculi are microchannels connecting the lacunae together. (c) Osteoblasts surround the exterior of the bone. Osteoclasts bore tunnels into the bone and osteocytes are found in the lacunae.

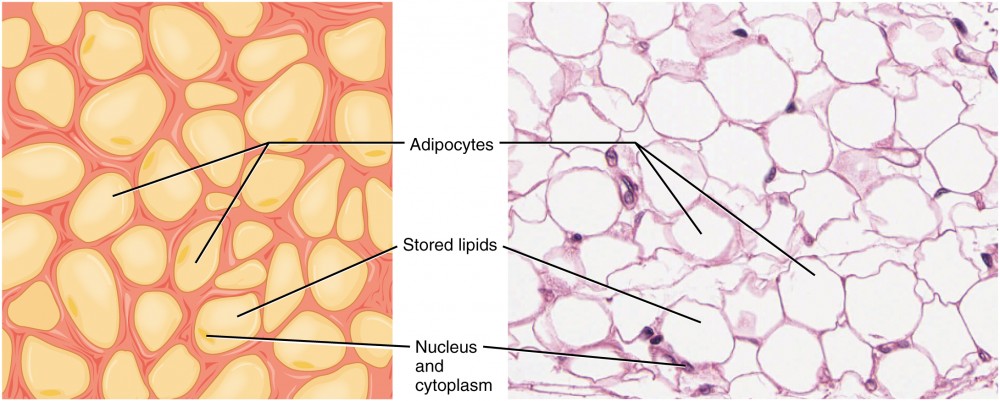

Adipose Tissue

Adipose tissue, or fat tissue, is considered a connective tissue even though it does not have fibroblasts or a real matrix and only has a few fibers. Adipose tissue is made up of cells called adipocytes that collect and store fat in the form of triglycerides, for energy metabolism. Adipose tissues additionally serve as insulation to help maintain body temperatures, allowing animals to be endothermic, and they function as cushioning against damage to body organs. Under a microscope, adipose tissue cells appear empty due to the extraction of fat during the processing of the material for viewing, as seen in (Figure 13). The thin lines in the image are the cell membranes, and the nuclei are the small, black dots at the edges of the cells.

Figure 13. Adipose Tissue. This is a loose connective tissue that consists of fat cells with little extracellular matrix. It stores fat for energy and provides insulation. LM × 800. (Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

Blood

Blood is considered a connective tissue because it has a matrix, as shown in (Figure 14). The living cell types are red blood cells (RBC), also called erythrocytes, and white blood cells (WBC), also called leukocytes. The fluid portion of whole blood, its matrix, is commonly called plasma.

Figure 14. Blood is a connective tissue that has a fluid matrix, called plasma, and no fibers. Erythrocytes (red blood cells), the predominant cell type, are involved in the transport of oxygen and carbon dioxide. Also present are various leukocytes (white blood cells) involved in immune response.

The cell found in greatest abundance in blood is the erythrocyte. Erythrocytes are counted in millions in a blood sample: the average number of red blood cells in primates is 4.7 to 5.5 million cells per microliter. Erythrocytes are consistently the same size in a species, but vary in size between species. For example, the average diameter of a primate red blood cell is 7.5 µl, a dog is close at 7.0 µl, but a cat’s RBC diameter is 5.9 µl. Sheep erythrocytes are even smaller at 4.6 µl. Mammalian erythrocytes lose their nuclei and mitochondria when they are released from the bone marrow where they are made. Fish, amphibian, and avian red blood cells maintain their nuclei and mitochondria throughout the cell’s life. The principal job of an erythrocyte is to carry and deliver oxygen to the tissues.

Leukocytes are the predominant white blood cells found in the peripheral blood. Leukocytes are counted in the thousands in the blood with measurements expressed as ranges: primate counts range from 4,800 to 10,800 cells per µl, dogs from 5,600 to 19,200 cells per µl, cats from 8,000 to 25,000 cells per µl, cattle from 4,000 to 12,000 cells per µl, and pigs from 11,000 to 22,000 cells per µl.

Lymphocytes function primarily in the immune response to foreign antigens or material. Different types of lymphocytes make antibodies tailored to the foreign antigens and control the production of those antibodies. Neutrophils are phagocytic cells and they participate in one of the early lines of defense against microbial invaders, aiding in the removal of bacteria that has entered the body. Another leukocyte that is found in the peripheral blood is the monocyte. Monocytes give rise to phagocytic macrophages that clean up dead and damaged cells in the body, whether they are foreign or from the host animal. Two additional leukocytes in the blood are eosinophils and basophils—both help to facilitate the inflammatory response.

The slightly granular material among the cells is a cytoplasmic fragment of a cell in the bone marrow. This is called a platelet or thrombocyte. Platelets participate in the stages leading up to coagulation of the blood to stop bleeding through damaged blood vessels. Blood has a number of functions, but primarily it transports material through the body to bring nutrients to cells and remove waste material from them.

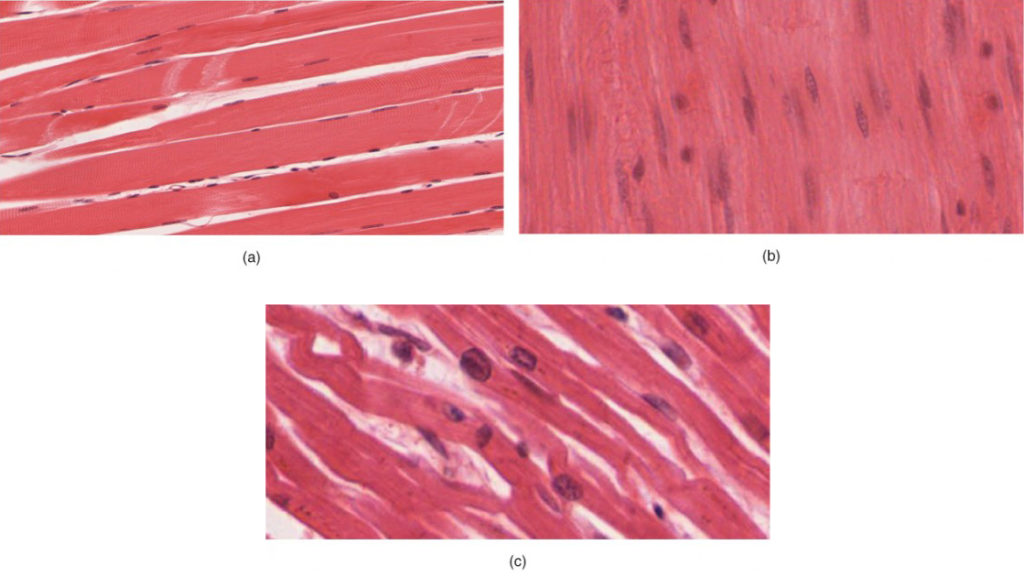

Muscle Tissues

There are three types of muscle in animal bodies: smooth, skeletal, and cardiac. They differ by the presence or absence of striations or bands, the number and location of nuclei, whether they are voluntarily or involuntarily controlled, and their location within the body. (Figure 15) summarizes these differences.

| Table 1. Comparison of Structure and Properties of Muscle Tissue Types | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | Histology | Function | Location |

| Skeletal | Long cylindrical fiber, striated, many peripherally located nuclei | Voluntary movement, produces heat, protects organs | Attached to bones and around entrance points to body (e.g., mouth, anus) |

| Cardiac | Short, branched, striated, single central nucleus | Contracts to pump blood | Heart |

| Smooth | Short, spindle-shaped, no evident striation, single nucleus in each fiber | Involuntary movement, moves food, involuntary control of respiration, moves secretions, regulates flow of blood in arteries by contraction | Walls of major organs and passageways, visceral organs |

Figure 15. Muscle Tissue. (a) Skeletal muscle cells have prominent striation and nuclei on their periphery. (b) Smooth muscle cells have a single nucleus and no visible striations. (c) Cardiac muscle cells appear striated and have a single nucleus. From top, LM × 1600, LM × 1600, LM × 1600. (Micrographs provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

Smooth Muscle

Smooth muscle does not have striations in its cells. It has a single, centrally located nucleus.. Constriction of smooth muscle occurs under involuntary, autonomic nervous control and in response to local conditions in the tissues. Smooth muscle tissue is also called non-striated as it lacks the banded appearance of skeletal and cardiac muscle. The walls of blood vessels, the tubes of the digestive system, and the tubes of the reproductive systems are composed of mostly smooth muscle.

Skeletal Muscle

Skeletal muscle has striations across its cells caused by the arrangement of the contractile proteins actin and myosin. These muscle cells are relatively long and have multiple nuclei along the edge of the cell. Skeletal muscle is under voluntary, somatic nervous system control and is found in the muscles that move bones.

Cardiac Muscle

Cardiac muscle is found only in the heart. Like skeletal muscle, it has cross striations in its cells, but cardiac muscle has a single, centrally located nucleus. Cardiac muscle is not under voluntary control but can be influenced by the autonomic nervous system to speed up or slow down. An added feature to cardiac muscle cells is a line than extends along the end of the cell as it abuts the next cardiac cell in the row. This line is called an intercalated disc: it assists in passing electrical impulse efficiently from one cell to the next and maintains the strong connection between neighboring cardiac cells.

Nervous Tissues

Nervous tissues are made of cells specialized to receive and transmit electrical impulses from specific areas of the body and to send them to specific locations in the body. Two main classes of cells make up nervous tissue: the neuron and neuroglia (Figure 16). The large structure with a central nucleus is the cell body of the neuron.

Figure 16. The Neuron. The cell body of a neuron, also called the soma, contains the nucleus and mitochondria. The dendrites transfer the nerve impulse to the soma. The axon carries the action potential away to another excitable cell. LM × 1600. (Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

Projections from the cell body are either dendrites specialized in receiving input or a single axon specialized in transmitting impulses. Some neuroglial cells are also shown. Astrocytes regulate the chemical environment of the nerve cell, and oligodendrocytes insulate the axon so the electrical nerve impulse is transferred more efficiently. Other glial cells that are not shown support the nutritional and waste requirements of the neuron. Some of the glial cells are phagocytic and remove debris or damaged cells from the tissue. A nerve consists of neurons and glial cells.

Figure 17. Nervous Tissue. Nervous tissue is made up of neurons and neuroglia. The cells of nervous tissue are specialized to transmit and receive impulses. LM × 872. (Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

Nervous tissue is characterized as being excitable and capable of sending and receiving electrochemical signals that provide the body with information. Neurons propagate information via electrochemical impulses, called action potentials, which are biochemically linked to the release of chemical signals. Neuroglia play an essential role in supporting neurons and modulating their information propagation.

Neurons display distinctive morphology, well suited to their role as conducting cells, with three main parts. The cell body includes most of the cytoplasm, the organelles, and the nucleus. Dendrites branch off the cell body and appear as thin extensions. A long “tail,” the axon, extends from the neuron body and can be wrapped in an insulating layer known as myelin, which is formed by accessory cells. The synapse is the gap between nerve cells, or between a nerve cell and its target, for example, a muscle or a gland, across which the impulse is transmitted by chemical compounds known as neurotransmitters.

Career Connections

Pathologist

A pathologist is a medical doctor or veterinarian who has specialized in the laboratory detection of disease in animals, including humans. These professionals complete medical school education and follow it with an extensive post-graduate residency at a medical center. A pathologist may oversee clinical laboratories for the evaluation of body tissue and blood samples for the detection of disease or infection. They examine tissue specimens through a microscope to identify cancers and other diseases. Some pathologists perform autopsies to determine the cause of death and the progression of disease.

Candela Citations

- Biology 2e. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: https://openstax.org/details/books/biology-2e. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/8d50a0af-948b-4204-a71d-4826cba765b8@8.19

- Chapter 4. Authored by: OpenStax College. Provided by: Rice University. Located at: http://openstaxcollege.org/files/textbook_version/low_res_pdf/13/col11496-lr.pdf. Project: Anatomy & Physiology. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/content/col11496/latest/