All of the organ systems of your body are interdependent, and the skeletal system is no exception. The food you take in via your digestive system and the hormones secreted by your endocrine system affect your bones. Even using your muscles to engage in exercise has an impact on your bones.

Exercise and Bone Tissue

During long space missions, astronauts can lose approximately 1 to 2 percent of their bone mass per month. This loss of bone mass is thought to be caused by the lack of mechanical stress on astronauts’ bones due to the low gravitational forces in space. Lack of mechanical stress causes bones to lose mineral salts and collagen fibers, and thus strength. Similarly, mechanical stress stimulates the deposition of mineral salts and collagen fibers. The internal and external structure of a bone will change as stress increases or decreases so that the bone is an ideal size and weight for the amount of activity it endures. That is why people who exercise regularly have thicker bones than people who are more sedentary. It is also why a broken bone in a cast atrophies while its contralateral mate maintains its concentration of mineral salts and collagen fibers. The bones undergo remodeling as a result of forces (or lack of forces) placed on them.

Numerous, controlled studies have demonstrated that people who exercise regularly have greater bone density than those who are more sedentary. Any type of exercise will stimulate the deposition of more bone tissue, but resistance training has a greater effect than cardiovascular activities. Resistance training is especially important to slow down the eventual bone loss due to aging and for preventing osteoporosis.

Nutrition and Bone Tissue

The vitamins and minerals contained in all of the food we consume are important for all of our organ systems. However, there are certain nutrients that affect bone health.

Calcium and Vitamin D

You already know that calcium is a critical component of bone, especially in the form of calcium phosphate and calcium carbonate. Since the body cannot make calcium, it must be obtained from the diet. However, calcium cannot be absorbed from the small intestine without vitamin D. Therefore, intake of vitamin D is also critical to bone health. In addition to vitamin D’s role in calcium absorption, it also plays a role, though not as clearly understood, in bone remodeling.

Milk and other dairy foods are not the only sources of calcium. This important nutrient is also found in green leafy vegetables, broccoli, and intact salmon and canned sardines with their soft bones. Nuts, beans, seeds, and shellfish provide calcium in smaller quantities.

Except for fatty fish like salmon and tuna, or fortified milk or cereal, vitamin D is not found naturally in many foods. The action of sunlight on the skin triggers the body to produce its own vitamin D (Figure 1), but many people, especially those of darker complexion and those living in northern latitudes where the sun’s rays are not as strong, are deficient in vitamin D. In cases of deficiency, a doctor can prescribe a vitamin D supplement.

Figure 1. Synthesis of Vitamin D. Sunlight is one source of vitamin D.

Other Nutrients

Vitamin K also supports bone mineralization and may have a synergistic role with vitamin D in the regulation of bone growth. Green leafy vegetables are a good source of vitamin K.

The minerals magnesium and fluoride may also play a role in supporting bone health. While magnesium is only found in trace amounts in the human body, more than 60 percent of it is in the skeleton, suggesting it plays a role in the structure of bone. Fluoride can displace the hydroxyl group in bone’s hydroxyapatite crystals and form fluorapatite. Similar to its effect on dental enamel, fluorapatite helps stabilize and strengthen bone mineral. Fluoride can also enter spaces within hydroxyapatite crystals, thus increasing their density.

Omega-3 fatty acids have long been known to reduce inflammation in various parts of the body. Inflammation can interfere with the function of osteoblasts, so consuming omega-3 fatty acids, in the diet or in supplements, may also help enhance production of new osseous tissue. Table 1 summarizes the role of nutrients in bone health.

| Table 1. Nutrients and Bone Health | |

|---|---|

| Nutrient | Role in bone health |

| Calcium | Needed to make calcium phosphate and calcium carbonate, which form the hydroxyapatite crystals that give bone its hardness |

| Vitamin D | Needed for calcium absorption |

| Vitamin K | Supports bone mineralization; may have synergistic effect with vitamin D |

| Magnesium | Structural component of bone |

| Fluoride | Structural component of bone |

| Omega-3 fatty acids | Reduces inflammation that may interfere with osteoblast function |

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and OSTeoArthritis

Rheumatoid Arthritis:

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic inflammatory disorder that may affect many tissues and organs, but principally attacks flexible (synovial) joints. The process involves an inflammatory response of the capsule around the joints (synovium) secondary to swelling (hyperplasia) of synovial cells, excess synovial fluid, and the development of fibrous tissue (pannus) in the synovium. The pathology of the disease process often leads to the destruction of articular cartilage and ankylosis (fusion) of the joints. Rheumatoid arthritis can also produce diffuse inflammation in the lungs, the membrane around the heart (pericardium), the membranes of the lung (pleura), and the white of the eye (sclera), and also nodular lesions, most common in subcutaneous tissue. Although the cause of rheumatoid arthritis is unknown, autoimmunity plays a pivotal role in both its chronicity and progression, and RA is considered a systemic autoimmune disease.

There are over 100 different forms of arthritis. The most common form, osteoarthritis (degenerative joint disease), is a result of trauma to the joint, infection of the joint, or age. The major complaint by individuals who have arthritis is joint pain. Pain is often a constant and may be localized to the joint affected. The pain from arthritis is due to inflammation that occurs around the joint, damage to the joint from disease, daily wear and tear of joint, muscle strains caused by forceful movements against stiff, painful joints, and fatigue

Osteoarthritis

Arthritis is the most common cause of disability in the United States. More than 20 million individuals with arthritis have severe limitations in function on a daily basis. Absenteeism and frequent visits to the physician are common in individuals who have arthritis. Arthritis makes it very difficult for individuals to be physically active and many become home bound. Treatment options vary depending on the type of arthritis and include physical therapy, lifestyle changes (including exercise and weight control), orthopedic bracing, and medications. Joint replacement surgery may be required in eroding forms of arthritis. Medications can help reduce inflammation in the joint which decreases pain. Moreover, by decreasing inflammation, the joint damage may be slowed

Hormones and Bone Tissue

The endocrine system produces and secretes hormones, many of which interact with the skeletal system. These hormones are involved in controlling bone growth, maintaining bone once it is formed, and remodeling it.

Hormones That Influence Osteoblasts and/or Maintain the Matrix

Several hormones are necessary for controlling bone growth and maintaining the bone matrix. The pituitary gland secretes growth hormone (GH), which, as its name implies, controls bone growth in several ways. It triggers chondrocyte proliferation in epiphyseal plates, resulting in the increasing length of long bones. GH also increases calcium retention, which enhances mineralization, and stimulates osteoblastic activity, which improves bone density.

GH is not alone in stimulating bone growth and maintaining osseous tissue. Thyroxine, a hormone secreted by the thyroid gland promotes osteoblastic activity and the synthesis of bone matrix. During puberty, the sex hormones (estrogen in girls, testosterone in boys) also come into play. They too promote osteoblastic activity and production of bone matrix, and in addition, are responsible for the growth spurt that often occurs during adolescence. They also promote the conversion of the epiphyseal plate to the epiphyseal line (i.e., cartilage to its bony remnant), thus bringing an end to the longitudinal growth of bones. Additionally, calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D, is produced by the kidneys and stimulates the absorption of calcium and phosphate from the digestive tract.

Aging and the Skeletal System

Figure 2. Graph Showing Relationship Between Age and Bone Mass. Bone density peaks at about 30 years of age. Women lose bone mass more rapidly than men.

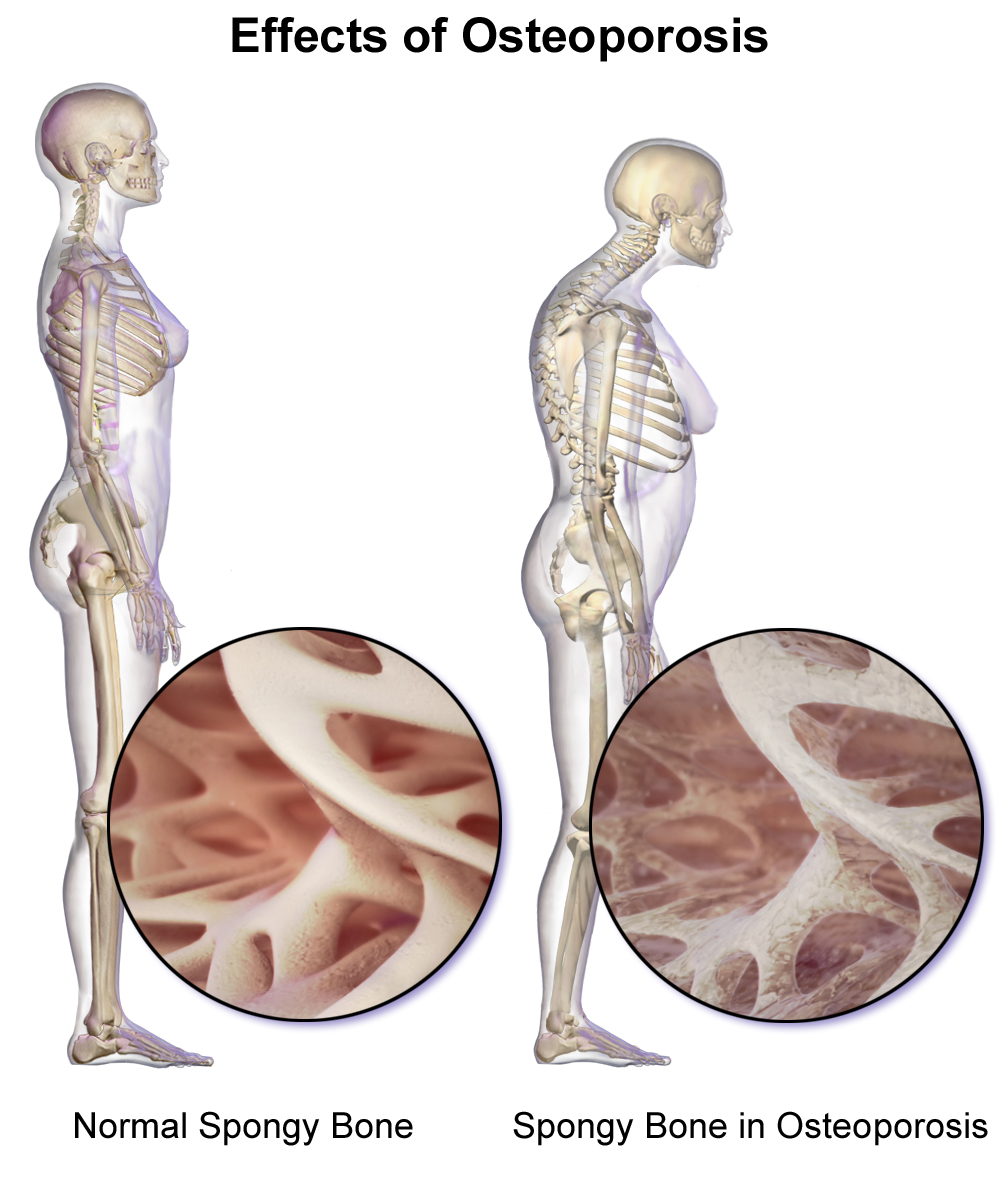

Figure 2 shows that women lose bone mass more quickly than men starting at about 50 years of age. This occurs because 50 is the approximate age at which women go through menopause. Not only do their menstrual periods lessen and eventually cease, but their ovaries reduce in size and then cease the production of estrogen, a hormone that promotes osteoblastic activity and production of bone matrix. Thus, osteoporosis is more common in women than in men, but men can develop it, too. Anyone with a family history of osteoporosis has a greater risk of developing the disease, so the best treatment is prevention, which should start with a childhood diet that includes adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D and a lifestyle that includes weight-bearing exercise. These actions, as discussed above, are important in building bone mass. Promoting proper nutrition and weight-bearing exercise early in life can maximize bone mass before the age of 30, thus reducing the risk of osteoporosis.

For many elderly people, a hip fracture can be life threatening. The fracture itself may not be serious, but the immobility that comes during the healing process can lead to the formation of blood clots that can lodge in the capillaries of the lungs, resulting in respiratory failure; pneumonia due to the lack of poor air exchange that accompanies immobility; pressure sores (bed sores) that allow pathogens to enter the body and cause infections; and urinary tract infections from catheterization.

Osteoporosis is the weakening of bones in the body. It is caused by lack of calcium deposited in the bones. This lack of calcium causes the bones to become brittle. They break easily. Side effects include limping. Some symptoms late in the disease include pain in the bones, bones breaking very easily and lower back pain due to spinal bone fractures. It is more likely for a woman to get osteoporosis than a man. Elderly people are more likely to develop osteoporosis than younger people. The amount of calcium in the bones decreases as a person gets older.

Treatment of Osteoporosis

There is no cure for osteoporosis. Osteoporosis risks can be reduced with lifestyle changes and sometimes medication, or treatment may involve both. Lifestyle change includes diet, exercise, and preventing falls. Medication includes calcium, vitamin D, bisphosphonates, and several others.

Consuming too much alcohol and caffeine can cause an increase in the risk of weak bones. Too much salt increases the amount of calcium lost in urine. This is bad because calcium makes bones strong. People should not take iron and calcium supplements at the same time. This is because calcium competes with the absorption of minerals such as iron.

Hormones That Influence Osteoclasts

Bone modeling and remodeling require osteoclasts to resorb unneeded, damaged, or old bone, and osteoblasts to lay down new bone. Two hormones that affect the osteoclasts are parathyroid hormone (PTH) and calcitonin.

PTH stimulates osteoclast proliferation and activity. As a result, calcium is released from the bones into the circulation, thus increasing the calcium ion concentration in the blood. PTH also promotes the reabsorption of calcium by the kidney tubules, which can affect calcium homeostasis (see below).

The small intestine is also affected by PTH, albeit indirectly. Because another function of PTH is to stimulate the synthesis of vitamin D, and because vitamin D promotes intestinal absorption of calcium, PTH indirectly increases calcium uptake by the small intestine. Calcitonin, a hormone secreted by the thyroid gland, has some effects that counteract those of PTH. Calcitonin inhibits osteoclast activity and stimulates calcium uptake by the bones, thus reducing the concentration of calcium ions in the blood. As evidenced by their opposing functions in maintaining calcium homeostasis, PTH and calcitonin are generally not secreted at the same time. Table 2 summarizes the hormones that influence the skeletal system.

| Table 2. Hormones That Affect the Skeletal System | |

|---|---|

| Hormone | Role |

| Growth hormone | Increases length of long bones, enhances mineralization, and improves bone density |

| Thyroxine | Stimulates bone growth and promotes synthesis of bone matrix |

| Sex hormones | Promote osteoblastic activity and production of bone matrix; responsible for adolescent growth spurt; promote conversion of epiphyseal plate to epiphyseal line |

| Calcitriol | Stimulates absorption of calcium and phosphate from digestive tract |

| Parathyroid hormone | Stimulates osteoclast proliferation and resorption of bone by osteoclasts; promotes reabsorption of calcium by kidney tubules; indirectly increases calcium absorption by small intestine |

| Calcitonin | Inhibits osteoclast activity and stimulates calcium uptake by bones |

Calcium Homeostasis: Interactions of the Skeletal System and Other Organ Systems

Calcium is not only the most abundant mineral in bone, it is also the most abundant mineral in the human body. Calcium ions are needed not only for bone mineralization but for tooth health, regulation of the heart rate and strength of contraction, blood coagulation, contraction of smooth and skeletal muscle cells, and regulation of nerve impulse conduction. The normal level of calcium in the blood is about 10 mg/dL. When the body cannot maintain this level, a person will experience hypo- or hypercalcemia.

Hypocalcemia, a condition characterized by abnormally low levels of calcium, can have an adverse effect on a number of different body systems including circulation, muscles, nerves, and bone. Without adequate calcium, blood has difficulty coagulating, the heart may skip beats or stop beating altogether, muscles may have difficulty contracting, nerves may have difficulty functioning, and bones may become brittle. The causes of hypocalcemia can range from hormonal imbalances to an improper diet. Treatments vary according to the cause, but prognoses are generally good.

Conversely, in hypercalcemia, a condition characterized by abnormally high levels of calcium, the nervous system is underactive, which results in lethargy, sluggish reflexes, constipation and loss of appetite, confusion, and in severe cases, coma.

Obviously, calcium homeostasis is critical. The skeletal, endocrine, and digestive systems play a role in this, but the kidneys do, too. These body systems work together to maintain a normal calcium level in the blood

Figure 3. Pathways in Calcium Homeostasis. The body regulates calcium homeostasis with two pathways; one is signaled to turn on when blood calcium levels drop below normal and one is the pathway that is signaled to turn on when blood calcium levels are elevated.

Calcium is a chemical element that cannot be produced by any biological processes. The only way it can enter the body is through the diet. The bones act as a storage site for calcium: The body deposits calcium in the bones when blood levels get too high, and it releases calcium when blood levels drop too low. This process is regulated by PTH, vitamin D, and calcitonin.

Cells of the parathyroid gland have plasma membrane receptors for calcium. When calcium is not binding to these receptors, the cells release PTH, which stimulates osteoclast proliferation and resorption of bone by osteoclasts. This demineralization process releases calcium into the blood. PTH promotes reabsorption of calcium from the urine by the kidneys, so that the calcium returns to the blood. Finally, PTH stimulates the synthesis of vitamin D, which in turn, stimulates calcium absorption from any digested food in the small intestine.

When all these processes return blood calcium levels to normal, there is enough calcium to bind with the receptors on the surface of the cells of the parathyroid glands, and this cycle of events is turned off

When blood levels of calcium get too high, the thyroid gland is stimulated to release calcitonin, which inhibits osteoclast activity and stimulates calcium uptake by the bones, but also decreases reabsorption of calcium by the kidneys. All of these actions lower blood levels of calcium. When blood calcium levels return to normal, the thyroid gland stops secreting calcitonin.

Candela Citations

- Chapter 6. Authored by: OpenStax College. Provided by: Rice University. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/14fb4ad7-39a1-4eee-ab6e-3ef2482e3e22@7.1@7.1.. Project: Anatomy & Physiology. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/content/col11496/latest/.