Learning Objectives

- Describe the functions of the skeletal system.

- Distinguish between long bones, short bones, flat bones, and irregular bones and provide an example of each.

- Identify the anatomical features of a long bone

- Describe the microscopic structure of compact bone, and compare it with that of spongy bone.

- Identify all the bones of the axial and appendicular skeleton.

- Describe various skeletal joints and the movements possible

- Describe the steps involved in bone development and bone repair

- Describe the effect exercise has on bone tissue

- Describe the disorders of the skeletal system

- Describe the effects of hormones on bone tissue, the process of calcium homeostasis

Bone, or osseous tissue, is a hard, dense connective tissue that forms most of the adult skeleton, the support structure of the body. In the areas of the skeleton where bones move (for example, the ribcage and joints), cartilage, a semi-rigid form of connective tissue, provides flexibility and smooth surfaces for movement.

The skeletal system is the body system composed of bones and cartilage and performs the following critical functions for the human body:

- protection of vital structures, such as the spinal cord, brain, heart, and lungs.

- support of body structures.

- body locomotion through coordination with the muscular system.

- hematopoiesis, or generation of blood cells, within the red marrow spaces of bones.

- storage and release of the inorganic minerals calcium and phosphorous, which are needed for functions such as muscle contraction and neural signal conduction.

The most apparent functions of the skeletal system are the gross functions—those visible by observation. Simply by looking at a person, you can see how the bones support, facilitate movement, and protect the human body.

Figure 1. Bones Protect Brain. The cranium completely surrounds and protects the brain from non-traumatic injury.

Just as the steel beams of a building provide a scaffold to support its weight, the bones and cartilage of your skeletal system compose the scaffold that supports the rest of your body. Without the skeletal system, you would be a limp mass of organs, muscle, and skin.

Bones also facilitate movement by serving as points of attachment for your muscles. While some bones only serve as a support for the muscles, others also transmit the forces produced when your muscles contract. From a mechanical point of view, bones act as levers and joints serve as fulcrums.

Unless a muscle spans a joint and contracts, a bone is not going to move. For information on the interaction of the skeletal and muscular systems, that is, the musculoskeletal system, seek additional content.

Bones also protect internal organs from injury by covering or surrounding them. For example, your ribs protect your lungs and heart, the bones of your vertebral column (spine) protect your spinal cord, and the bones of your cranium (skull) protect your brain (Figure 1).

Career Connection: Orthopedist

An orthopedist is a doctor who specializes in diagnosing and treating disorders and injuries related to the musculoskeletal system. Some orthopedic problems can be treated with medications, exercises, braces, and other devices, but others may be best treated with surgery (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Arm Brace. An orthopedist will sometimes prescribe the use of a brace that reinforces the underlying bone structure it is being used to support. (credit: Juhan Sonin)

While the origin of the word “orthopedics” (ortho- = “straight”; paed- = “child”), literally means “straightening of the child,” orthopedists can have patients who range from pediatric to geriatric. In recent years, orthopedists have even performed prenatal surgery to correct spina bifida, a congenital defect in which the neural canal in the spine of the fetus fails to close completely during embryologic development.

Orthopedists commonly treat bone and joint injuries but they also treat other bone conditions including curvature of the spine. Lateral curvatures (scoliosis) can be severe enough to slip under the shoulder blade (scapula) forcing it up as a hump. Spinal curvatures can also be excessive dorsoventrally (kyphosis) causing a hunch back and thoracic compression. These curvatures often appear in preteens as the result of poor posture, abnormal growth, or indeterminate causes. Mostly, they are readily treated by orthopedists. As people age, accumulated spinal column injuries and diseases like osteoporosis can also lead to curvatures of the spine, hence the stooping you sometimes see in the elderly.

Some orthopedists sub-specialize in sports medicine, which addresses both simple injuries, such as a sprained ankle, and complex injuries, such as a torn rotator cuff in the shoulder. Treatment can range from exercise to surgery.

Mineral Storage, Energy Storage, and Hematopoiesis

Figure 3. Head of Femur Showing Red and Yellow Marrow. The head of the femur contains both yellow and red marrow. Yellow marrow stores fat. Red marrow is responsible for hematopoiesis. (credit: modification of work by “stevenfruitsmaak”/Wikimedia Commons)

On a metabolic level, bone tissue performs several critical functions. For one, the bone matrix acts as a reservoir for a number of minerals important to the functioning of the body, especially calcium, and potassium. These minerals, incorporated into bone tissue, can be released back into the bloodstream to maintain levels needed to support physiological processes. Calcium ions, for example, are essential for muscle contractions and controlling the flow of other ions involved in the transmission of nerve impulses.

Bone also serves as a site for fat storage and blood cell production. The softer connective tissue that fills the interior of most bone is referred to as bone marrow (Figure 3). There are two types of bone marrow: yellow marrow and red marrow. Yellow marrow contains adipose tissue; the triglycerides stored in the adipocytes of the tissue can serve as a source of energy. Red marrow is where hematopoiesis—the production of blood cells—takes place. Red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets are all produced in the red marrow.

Classify bones according to their shapes

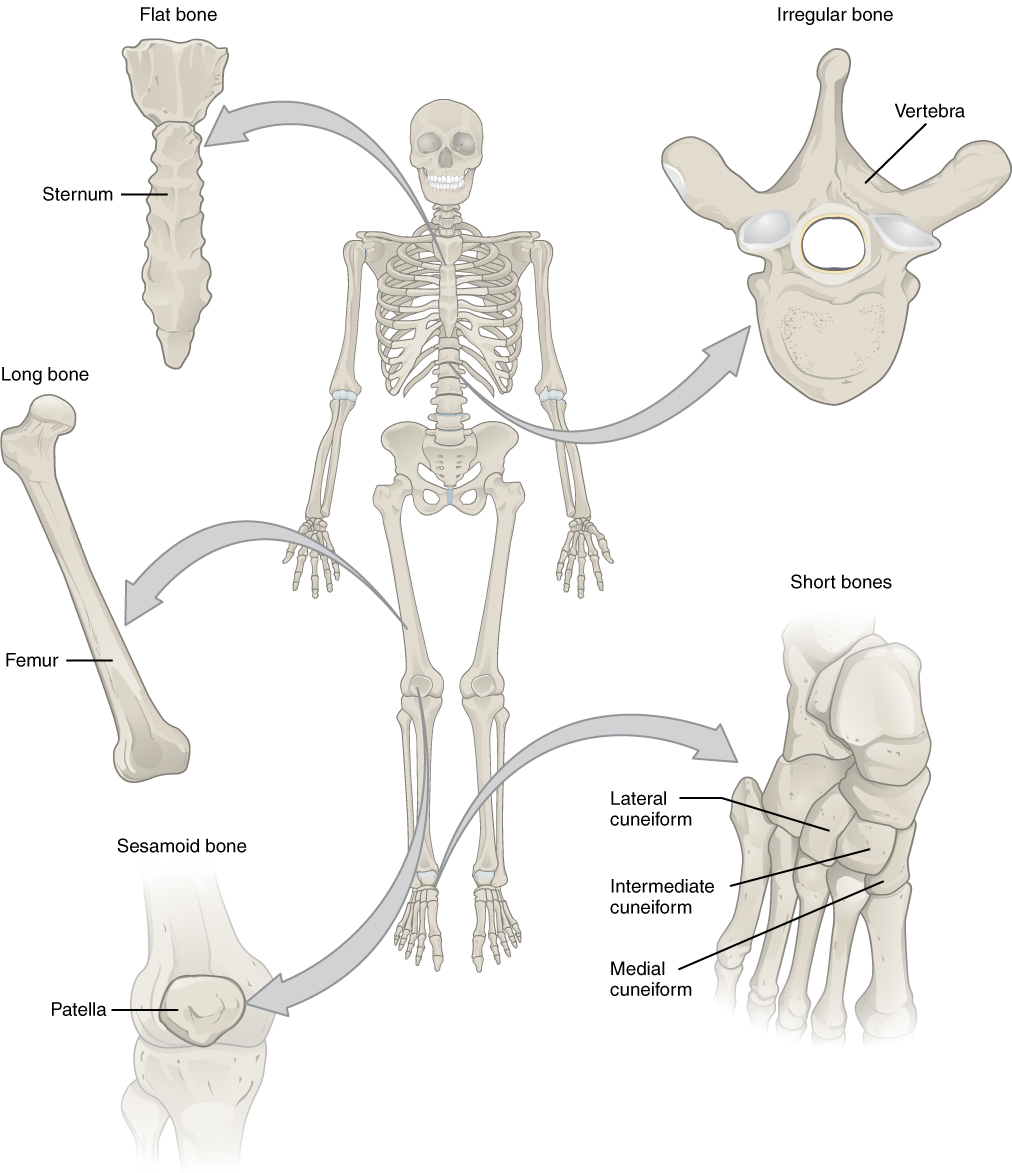

The 206 bones that compose the adult skeleton are divided into five categories based on their shapes (Figure 4). Their shapes and their functions are related such that each categorical shape of bone has a distinct function.

Figure 4. Classifications of Bones. Bones are classified according to their shape.

Long Bones: A long bone is one that is cylindrical in shape, being longer than it is wide. Keep in mind, however, that the term describes the shape of a bone, not its size. Long bones are found in the arms (humerus, ulna, radius) and legs (femur, tibia, fibula), as well as in the fingers (metacarpals, phalanges) and toes (metatarsals, phalanges). Long bones function as levers; they move when muscles contract.

Short Bones: A short bone is one that is cube-like in shape, being approximately equal in length, width, and thickness. The only short bones in the human skeleton are in the carpals of the wrists and the tarsals of the ankles. Short bones provide stability and support as well as some limited motion.

Flat Bones: The term flat bone is somewhat of a misnomer because, although a flat bone is typically thin, it is also often curved. Examples include the cranial (skull) bones, the scapulae (shoulder blades), the sternum (breastbone), and the ribs. Flat bones serve as points of attachment for muscles and often protect internal organs.

Irregular Bones: An irregular bone is one that does not have any easily characterized shape and therefore does not fit any other classification. These bones tend to have more complex shapes, like the vertebrae that support the spinal cord and protect it from compressive forces. Many facial bones, particularly the ones containing sinuses, are classified as irregular bones.

Sesamoid Bones: A sesamoid bone is a small, round bone that, as the name suggests, is shaped like a sesame seed. These bones form in tendons (the sheaths of tissue that connect bones to muscles) where a great deal of pressure is generated in a joint. The sesamoid bones protect tendons by helping them overcome compressive forces. Sesamoid bones vary in number and placement from person to person but are typically found in tendons associated with the feet, hands, and knees. The patellae (singular = patella) are the only sesamoid bones found in common with every person. Table 1 reviews bone classifications with their associated features, functions, and examples.

| Table 1. Bone Classifications | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone classification | Features | Function(s) | Examples |

| Long | Cylinder-like shape, longer than it is wide | Leverage | Femur, tibia, fibula, metatarsals, humerus, ulna, radius, metacarpals, phalanges |

| Short | Cube-like shape, approximately equal in length, width, and thickness | Provide stability, support, while allowing for some motion | Carpals, tarsals |

| Flat | Thin and curved | Points of attachment for muscles; protectors of internal organs | Sternum, ribs, scapulae, cranial bones |

| Irregular | Complex shape | Protect internal organs | Vertebrae, facial bones |

| Sesamoid | Small and round; embedded in tendons | Protect tendons from compressive forces | Patellae |

Candela Citations

- Chapter 6. Authored by: OpenStax College. Provided by: Rice University. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/14fb4ad7-39a1-4eee-ab6e-3ef2482e3e22@15.1.. Project: Anatomy & Physiology. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/content/col11496/latest/