Introduction: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Like his contemporary Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892), Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wedded sound and sense in epic poetry on the nation’s lore and history. Unlike Tennyson, Longfellow drew not upon Arthurian legend but upon American stories and legends. He wrote about Native American lives, particularly that of the Ojibwe in The Song of Hiawatha (1855) and the Plymouth Colony in The Courtship of Miles Standish (1858). The metrical facility, flexible rhyming, and romantic characterizations in Longfellow’s poetry made his work immensely popular with readers in both America and England. However, he was dismissed by later generations for a time as overly traditional and didactic. Now, readers appreciate the nuance and diversity, wide-ranging scholarship, and linguistic knowledge available in Longfellow’s work. With T. S. Eliot, Longfellow is the only American poet memorialized at Westminster Abbey’s Poet’s Corner.

Born in Maine, Longfellow studied there, first at Portland Academy then at Bowdoin College, where Nathaniel Hawthorne and Franklin Pierce were among his classmates. Upon graduation, he was offered a professorship of modern languages at Bowdoin. To prepare for this position, Longfellow traveled to Europe, visiting France, Spain, Italy, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and England. Longfellow translated from the original the texts he taught at Bowdoin, to the neglect of his own creative work. In 1831, he married Mary Storer Potter (1812–1835) and published prose travel pieces in The New-England Magazine. From 1835 to 1836, he once more traveled abroad to prepare for another teaching position, at Harvard University, for which he acquired a greater knowledge of Germanic and Scandinavian languages. While in Holland, his wife miscarried and died. While touring Austria and Switzerland, he met Fanny Appleton, the woman he would marry seven years later.

Residing at Craigie House in Cambridge, a wedding gift from his wealthy, industrialist father-in-law, Longfellow became a leading literary figure not only in New England but also across the nation. He consolidated this position by leaving academic life in 1854 to devote himself entirely to writing. In 1861, Fanny Appleton Longfellow was burned to death after her dress caught fire; subsequently, Longfellow’s cosmopolitan and religious interests came to the fore in such works as a three-volume translation in unrhymed triplets of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1865–1871) and Christus: A Mystery, published in three parts (1872).

The Song of Hiawatha – Excerpts (1855)

III.

HIAWATHA’S CHILDHOOD.

In the days that are forgotten,

In the unremembered ages,

From the full moon fell Nokomis,

Fell the beautiful Nokomis,

She a wife but not a mother.

She was sporting with her women,

Swinging in a swing of grape-vines,

When her rival, the rejected,

Full of jealousy and hatred,

Cut the leafy swing asunder,

Cut in twain the twisted grape-vines,

And Nokomis fell affrighted

Downward through the evening twilight,

On the Muskoday, the meadow,

On the prairie full of blossoms.

“See! a star falls!” said the people;

“From the sky a star is falling!”

There among the ferns and mosses,

There among the prairie lilies,

On the Muskoday, the meadow,

In the moonlight and the starlight,

Fair Nokomis bore a daughter.

And she called her name Wenonah,

As the first-born of her daughters.

And the daughter of Nokomis

Grew up like the prairie lilies,

Grew a tall and slender maiden,

With the beauty of the moonlight,

With the beauty of the starlight.

And Nokomis warned her often,

Saying oft, and oft repeating,

“Oh, beware of Mudjekeewis,

Of the West-Wind, Mudjekeewis;

Listen not to what he tells you;

Lie not down upon the meadow,

Stoop not down among the lilies,

Lest the West-Wind come and harm you!”

But she heeded not the warning,

Heeded not those words of wisdom.

And the West-Wind came at evening,

Walking lightly o’er the prairie,

Whispering to the leaves and blossoms,

Bending low the flowers and grasses,

Found the beautiful Wenonah,

Lying there among the lilies,

Wooed her with his words of sweetness,

Wooed her with his soft caresses,

Till she bore a son in sorrow,

Bore a son of love and sorrow,

Thus was born my Hiawatha,

Thus was born the child of wonder;

But the daughter of Nokomis,

Hiawatha’s gentle mother,

55In her anguish died deserted

By the West-Wind, false and faithless,

By the heartless Mudjekeewis.

For her daughter, long and loudly

Wailed and wept the sad Nokomis;

“Oh that I were dead!” she murmured,

“Oh that I were dead, as thou art!

No more work, and no more weeping,

Wahonowin! Wahonowin!”

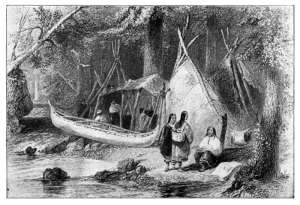

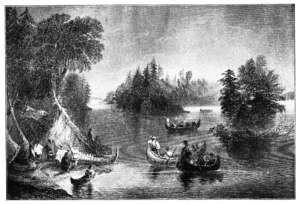

By the shores of Gitche Gumee,

By the shining Big-Sea-Water,

Stood the wigwam of Nokomis

Daughter of the Moon, Nokomis.

Dark behind it rose the forest,

Rose the black and gloomy pine-trees,

Rose the firs with cones upon them;

Bright before it beat the water,

Beat the clear and sunny water,

Beat the shining Big-Sea-Water.

There the wrinkled old Nokomis

Nursed the little Hiawatha,

Rocked him in his linden cradle,

Bedded soft in moss and rushes,

Safely bound with reindeer sinews;

Stilled his fretful wail by saying,

“Hush! the Naked Bear will hear thee!”

Lulled him into slumber, singing,

“Ewa-yea! my little owlet!

Who is this, that lights the wigwam?

With his great eyes lights the wigwam?

Ewa-yea! my little owlet!”

Many things Nokomis taught him

Of the stars that shine in heaven;

Showed him Ishkoodah, the comet,

Ishkoodah, with fiery tresses;

Showed the Death-Dance of the spirits,

Warriors with their plumes and war-clubs

Flaring far away to northward

In the frosty nights of Winter;

Showed the broad white road in heaven,

Pathway of the ghosts, the shadows,

Running straight across the heavens,

Crowded with the ghosts, the shadows.

At the door on summer evenings

Sat the little Hiawatha;

Heard the whispering of the pine-trees,

Heard the lapping of the waters,

Sounds of music, words of wonder;

“Minne-wawa!” said the pine-trees.

“Mudway-aushka!” said the water.

Saw the fire-fly, Wah-wah-taysee,

Flitting through the dusk of evening,

With the twinkle of its candle

Lighting up the brakes and bushes,

And he sang the song of children,

Sang the song Nokomis taught him:

“Wah-wah-taysee, little fire-fly,

Little, flitting, white-fire insect,

Little, dancing, white-fire creature,

Light me with your little candle,

115Ere upon my bed I lay me,

Ere in sleep I close my eyelids!”

Saw the moon rise from the water

Rippling, rounding from the water,

Saw the flecks and shadows on it,

Whispered, “What is that, Nokomis?”

And the good Nokomis answered:

“Once a warrior, very angry,

Seized his grandmother, and threw her

Up into the sky at midnight;

Right against the moon he threw her;

‘T is her body that you see there.”

Saw the rainbow in the heaven,

In the eastern sky, the rainbow,

Whispered, “What is that, Nokomis?”

And the good Nokomis answered:

“‘T is the heaven of flowers you see there;

All the wild-flowers of the forest,

All the lilies of the prairie,

When on earth they fade and perish,

Blossom in that heaven above us.”

When he heard the owls at midnight,

Hooting, laughing in the forest,

“What is that?” he cried in terror;

“What is that,” he said, “Nokomis?”

And the good Nokomis answered:

“That is but the owl and owlet,

Talking in their native language,

Talking, scolding at each other.”

Then the little Hiawatha

Learned of every bird its language,

Learned their names and all their secrets,

How they built their nests in Summer,

Where they hid themselves in Winter,

Talked with them whene’er he met them,

Called them “Hiawatha’s Chickens.”

Of all beasts he learned the language,

Learned their names and all their secrets,

How the beavers built their lodges,

Where the squirrels hid their acorns,

How the reindeer ran so swiftly,

Why the rabbit was so timid,

Talked with them whene’er he met them,

Called them “Hiawatha’s Brothers.”

Then Iagoo, the great boaster,

He the marvellous story-teller,

He the traveller and the talker,

He the friend of old Nokomis,

Made a bow for Hiawatha;

From a branch of ash he made it,

From an oak-bough made the arrows,

Tipped with flint, and winged with feathers,

And the cord he made of deer-skin.

Then he said to Hiawatha:

“Go, my son, into the forest,

Where the red deer herd together,

Kill for us a famous roebuck,

Kill for us a deer with antlers!”

Forth into the forest straightway

All alone walked Hiawatha

Proudly, with his bow and arrows;

And the birds sang round him, o’er him,

“Do not shoot us, Hiawatha!”

Sang the Opechee, the robin,

Sang the bluebird, the Owaissa,

“Do not shoot us, Hiawatha!”

Up the oak-tree, close beside him,

Sprang the squirrel, Adjidaumo,

In and out among the branches,

Coughed and chattered from the oak-tree,

Laughed, and said between his laughing,

“Do not shoot me, Hiawatha!”

And the rabbit from his pathway

Leaped aside, and at a distance

Sat erect upon his haunches,

Half in fear and half in frolic,

Saying to the little hunter,

“Do not shoot me, Hiawatha!”

But he heeded not, nor heard them,

For his thoughts were with the red deer;

On their tracks his eyes were fastened,

Leading downward to the river,

To the ford across the river,

And as one in slumber walked he.

Hidden in the alder-bushes,

There he waited till the deer came,

Till he saw two antlers lifted,

Saw two eyes look from the thicket,

Saw two nostrils point to windward,

And a deer came down the pathway,

Flecked with leafy light and shadow.

And his heart within him fluttered,

Trembled like the leaves above him,

Like the birch-leaf palpitated,

As the deer came down the pathway.

Then, upon one knee uprising,

Hiawatha aimed an arrow;

Scarce a twig moved with his motion,

Scarce a leaf was stirred or rustled,

But the wary roebuck started,

Stamped with all his hoofs together,

Listened with one foot uplifted,

Leaped as if to meet the arrow;

Ah! the singing, fatal arrow;

Like a wasp it buzzed and stung him!

Dead he lay there in the forest,

By the ford across the river;

Beat his timid heart no longer,

But the heart of Hiawatha

Throbbed and shouted and exulted,

As he bore the red deer homeward,

And Iagoo and Nokomis

Hailed his coming with applauses.

From the red deer’s hide Nokomis

Made a cloak for Hiawatha,

From the red deer’s flesh Nokomis

Made a banquet in his honor.

All the village came and feasted,

All the guests praised Hiawatha,

Called him Strong-Heart, Soan-ge-taha!

Called him Loon-Heart, Mahn-go-taysee!

IV.

HIAWATHA AND MUDJEKEEWIS.

Now had grown my Hiawatha,

Skilled in all the craft of hunters,

Learned in all the lore of old men,

In all youthful sports and pastimes,

In all manly arts and labors.

Swift of foot was Hiawatha;

He could shoot an arrow from him,

And run forward with such fleetness,

That the arrow fell behind him!

Strong of arm was Hiawatha;

He could shoot ten arrows upward,

Shoot them with such strength and swiftness,

That the tenth had left the bow-string

Ere the first to earth had fallen!

He had mittens, Minjekahwun,

Magic mittens made of deer-skin;

When upon his hands he wore them,

He could smite the rocks asunder,

He could grind them into powder.

He had moccasins enchanted,

Magic moccasins of deer-skin;

When he bound them round his ankles,

When upon his feet he tied them,

At each stride a mile he measured!

Much he questioned old Nokomis

Of his father Mudjekeewis;

Learned from her the fatal secret

Of the beauty of his mother,

Of the falsehood of his father;

And his heart was hot within him,

Like a living coal his heart was.

Then he said to old Nokomis,

“I will go to Mudjekeewis,

See how fares it with my father,

At the doorways of the West-Wind,

At the portals of the Sunset!”

From his lodge went Hiawatha,

Dressed for travel, armed for hunting;

Dressed in deer-skin shirt and leggings,

Richly wrought with quills and wampum

On his head his eagle-feathers,

Round his waist his belt of wampum,

In his hand his bow of ash-wood,

Strung with sinews of the reindeer;

In his quiver oaken arrows,

Tipped with jasper, winged with feathers;

With his mittens, Minjekahwun,

With his moccasins enchanted.

Warning said the old Nokomis,

“Go not forth, O Hiawatha!

To the kingdom of the West-Wind,

To the realms of Mudjekeewis,

Lest he harm you with his magic,

Lest he kill you with his cunning!”

But the fearless Hiawatha

Heeded not her woman’s warning;

Forth he strode into the forest,

At each stride a mile he measured;

Lurid seemed the sky above him,

Lurid seemed the earth beneath him,

Hot and close the air around him,

Filled with smoke and fiery vapors,

As of burning woods and prairies.

For his heart was hot within him,

Like a living coal his heart was.

So he journeyed westward, westward,

Left the fleetest deer behind him,

Left the antelope and bison;

Crossed the rushing Esconaba,

Crossed the mighty Mississippi,

Passed the Mountains of the Prairie,

Passed the land of Crows and Foxes,

Passed the dwellings of the Blackfeet,

Came unto the Rocky Mountains,

To the kingdom of the West-Wind,

Where upon the gusty summits

Sat the ancient Mudjekeewis,

Ruler of the winds of heaven.

Filled with awe was Hiawatha

At the aspect of his father.

On the air about him wildly

Tossed and streamed his cloudy tresses,

Gleamed like drifting snow his tresses,

Glared like Ishkoodah, the comet,

Like the star with fiery tresses.

Filled with joy was Mudjekeewis

When he looked on Hiawatha,

Saw his youth rise up before him

In the face of Hiawatha,

Saw the beauty of Wenonah

From the grave rise up before him.

“Welcome!” said he, “Hiawatha,

To the kingdom of the West-Wind!

Long have I been waiting for you!

Youth is lovely, age is lonely,

Youth is fiery, age is frosty;

You bring back the days departed,

You bring back my youth of passion,

And the beautiful Wenonah!”

Many days they talked together,

Questioned, listened, waited, answered;

Much the mighty Mudjekeewis

Boasted of his ancient prowess,

Of his perilous adventures,

His indomitable courage,

His invulnerable body.

Patiently sat Hiawatha,

Listening to his father’s boasting;

With a smile he sat and listened,

Uttered neither threat nor menace,

Neither word nor look betrayed him,

But his heart was hot within him,

Like a living coal his heart was.

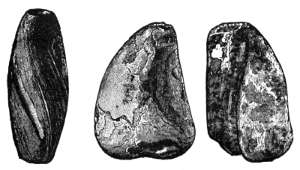

Then he said, “O Mudjekeewis,

Is there nothing that can harm you?

Nothing that you are afraid of?”

And the mighty Mudjekeewis,

Grand and gracious in his boasting,

Answered, saying, “There is nothing,

Nothing but the black rock yonder,

Nothing but the fatal Wawbeek!”

And he looked at Hiawatha

With a wise look and benignant,

With a countenance paternal,

Looked with pride upon the beauty

Of his tall and graceful figure,

Saying, “O my Hiawatha!

Is there anything can harm you?

Anything you are afraid of?”

But the wary Hiawatha

Paused awhile, as if uncertain,

Held his peace, as if resolving,

And then answered, “There is nothing,

Nothing but the bulrush yonder,

Nothing but the great Apukwa!”

And as Mudjekeewis, rising,

Stretched his hand to pluck the bulrush,

Hiawatha cried in terror,

Cried in well-dissembled terror,

“Kago! kago! do not touch it!”

“Ah, kaween!” said Mudjekeewis,

“No indeed, I will not touch it!”

Then they talked of other matters;

First of Hiawatha’s brothers,

First of Wabun, of the East-Wind,

Of the South-Wind, Shawondasee,

Of the North, Kabibonokka;

Then of Hiawatha’s mother,

Of the beautiful Wenonah,

Of her birth upon the meadow,

Of her death, as old Nokomis

Had remembered and related.

And he cried, “O Mudjekeewis,

It was you who killed Wenonah,

Took her young life and her beauty,

Broke the Lily of the Prairie,

Trampled it beneath your footsteps;

You confess it! you confess it!”

And the mighty Mudjekeewis

Tossed his gray hairs to the West-Wind,

Bowed his hoary head in anguish,

With a silent nod assented.

And with threatening look and gesture

Laid his hand upon the black rock,

On the fatal Wawbeek laid it,

With his mittens, Minjekahwun,

Rent the jutting crag asunder,

Smote and crushed it into fragments,

Hurled them madly at his father,

The remorseful Mudjekeewis,

For his heart was hot within him,

Like a living coal his heart was.

But the ruler of the West-Wind

Blew the fragments backward from him,

With the breathing of his nostrils,

With the tempest of his anger,

Blew them back at his assailant;

Seized the bulrush, the Apukwa,

Dragged it with its roots and fibres

From the margin of the meadow,

From its ooze, the giant bulrush;

Long and loud laughed Hiawatha!

Then began the deadly conflict,

Hand to hand among the mountains;

From his eyry screamed the eagle,

The Keneu, the great war-eagle,

Sat upon the crags around them,

Wheeling flapped his wings above them.

Like a tall tree in the tempest

Bent and lashed the giant bulrush;

And in masses huge and heavy

Crashing fell the fatal Wawbeek;

Till the earth shook with the tumult

And confusion of the battle,

And the air was full of shoutings,

And the thunder of the mountains,

Starting, answered, “Baim-wawa!”

Back retreated Mudjekeewis,

Rushing westward o’er the mountains,

Stumbling westward down the mountains

Three whole days retreated fighting,

Still pursued by Hiawatha

To the doorways of the West-Wind,

To the portals of the Sunset,

To the earth’s remotest border,

Where into the empty spaces

Sinks the sun, as a flamingo

Drops into her nest at nightfall,

In the melancholy marshes.

“Hold!” at length cried Mudjekeewis,

“Hold, my son, my Hiawatha!

‘T is impossible to kill me,

For you cannot kill the immortal.

I have put you to this trial,

But to know and prove your courage;

Now receive the prize of valor!

“Go back to your home and people,

Live among them, toil among them,

Cleanse the earth from all that harms it,

Clear the fishing-grounds and rivers,

Slay all monsters and magicians,

All the giants, the Wendigoes,

All the serpents, the Kenabeeks,

As I slew the Mishe-Mokwa,

Slew the Great Bear of the mountains.

“And at last when Death draws near you,

When the awful eyes of Pauguk

Glare upon you in the darkness,

I will share my kingdom with you,

Ruler shall you be thenceforward

Of the Northwest-Wind, Keewaydin,

Of the home-wind, the Keewaydin.”

Thus was fought that famous battle

In the dreadful days of Shah-shah,

In the days long since departed,

In the kingdom of the West-Wind.

Still the hunter sees its traces

Scattered far o’er hill and valley;

Sees the giant bulrush growing

By the ponds and water-courses,

Sees the masses of the Wawbeek

Lying still in every valley.

Homeward now went Hiawatha;

Pleasant was the landscape round him,

Pleasant was the air above him,

For the bitterness of anger

Had departed wholly from him,

From his brain the thought of vengeance,

From his heart the burning fever.

Only once his pace he slackened,

Only once he paused or halted,

Paused to purchase heads of arrows

Of the ancient Arrow-maker,

In the land of the Dacotahs,

Where the Falls of Minnehaha

Flash and gleam among the oak-trees,

Laugh and leap into the valley.

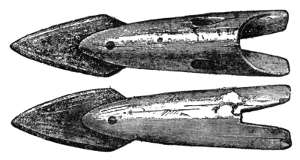

There the ancient Arrow-maker

Made his arrow-heads of sandstone,

Arrow-heads of chalcedony,

Arrow-heads of flint and jasper,

Smoothed and sharpened at the edges,

Hard and polished, keen and costly.

With him dwelt his dark-eyed daughter,

Wayward as the Minnehaha,

With her moods of shade and sunshine,

Eyes that smiled and frowned alternate,

Feet as rapid as the river,

Tresses flowing like the water,

And as musical a laughter;

And he named her from the river,

From the water-fall he named her,

Minnehaha, Laughing Water.

Was it then for heads of arrows,

Arrow-heads of chalcedony,

Arrow-heads of flint and jasper,

That my Hiawatha halted

In the land of the Dacotahs?

Was it not to see the maiden,

See the face of Laughing Water

Peeping from behind the curtain,

Hear the rustling of her garments

From behind the waving curtain,

As one sees the Minnehaha

Gleaming, glancing through the branches,

As one hears the Laughing Water

From behind its screen of branches?

Who shall say what thoughts and visions

Fill the fiery brains of young men?

Who shall say what dreams of beauty

Filled the heart of Hiawatha?

All he told to old Nokomis,

When he reached the lodge at sunset,

Was the meeting with his father,

Was his fight with Mudjekeewis;

Not a word he said of arrows,

Not a word of Laughing Water!

V.

HIAWATHA’S FASTING.

Prayed and fasted in the forest,

Not for greater skill in hunting,

Not for greater craft in fishing,

Not for triumphs in the battle,

And renown among the warriors,

But for profit of the people,

For advantage of the nations.

First he built a lodge for fasting,

Built a wigwam in the forest,

By the shining Big-Sea-Water,

In the blithe and pleasant Spring-time,

In the Moon of Leaves he built it,

And, with dreams and visions many,

Seven whole days and nights he fasted.

On the first day of his fasting

Through the leafy woods he wandered;

Saw the deer start from the thicket,

Saw the rabbit in his burrow,

Heard the pheasant, Bena, drumming,

Heard the squirrel, Adjidaumo,

Rattling in his hoard of acorns,

Saw the pigeon, the Omeme,

Building nests among the pine-trees,

And in flocks the wild goose, Wawa,

Flying to the fen-lands northward,

Whirring, wailing far above him.

“Master of Life!” he cried, desponding,

“Must our lives depend on these things?”

On the next day of his fasting

By the river’s brink he wandered,

Through the Muskoday, the meadow,

Saw the wild rice, Mahnomonee,

Saw the blueberry, Meenahga,

And the strawberry, Odahmin,

And the gooseberry, Shahbomin,

And the grape-vine, the Bemahgut,

Trailing o’er the alder-branches,

Filling all the air with fragrance!

“Master of Life!” he cried, desponding,

“Must our lives depend on these things?”

On the third day of his fasting

By the lake he sat and pondered,

By the still, transparent water;

Saw the sturgeon, Nahma, leaping,

Scattering drops like beads of wampum,

Saw the yellow perch, the Sahwa,

Like a sunbeam in the water,

Saw the pike, the Maskenozha,

And the herring, Okahahwis,

And the Shawgashee, the craw-fish!

“Master of Life!” he cried, desponding,

“Must our lives depend on these things?”

On the fourth day of his fasting

In his lodge he lay exhausted;

From his couch of leaves and branches

Gazing with half-open eyelids,

Full of shadowy dreams and visions,

On the dizzy, swimming landscape,

On the gleaming of the water,

On the splendor of the sunset.

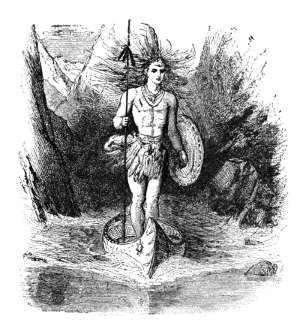

And he saw a youth approaching,

Dressed in garments green and yellow,

Coming through the purple twilight,

Through the splendor of the sunset;

Plumes of green bent o’er his forehead,

And his hair was soft and golden.

Standing at the open doorway,

Long he looked at Hiawatha,

Looked with pity and compassion

On his wasted form and features,

And, in accents like the sighing

Of the South-Wind in the tree-tops,

Said he, “O my Hiawatha!

All your prayers are heard in heaven,

For you pray not like the others;

Not for greater skill in hunting,

Not for greater craft in fishing,

Not for triumph in the battle,

Nor renown among the warriors,

But for profit of the people,

For advantage of the nations.

“From the Master of Life descending,

I, the friend of man, Mondamin,

Come to warn you and instruct you,

How by struggle and by labor

You shall gain what you have prayed for.

Rise up from your bed of branches,

Rise, O youth, and wrestle with me!”

Faint with famine, Hiawatha

Started from his bed of branches,

From the twilight of his wigwam

Forth into the flush of sunset

Came, and wrestled with Mondamin;

At his touch he felt new courage

Throbbing in his brain and bosom,

Felt new life and hope and vigor

Run through every nerve and fibre.

So they wrestled there together

In the glory of the sunset,

And the more they strove and struggled,

Stronger still grew Hiawatha;

Till the darkness fell around them,

And the heron, the Shuh-shuh-gah,

From her haunts among the fen-lands,

Gave a cry of lamentation,

Gave a scream of pain and famine.

“‘T is enough!” then said Mondamin,

Smiling upon Hiawatha,

I will come again to try you.”

And he vanished, and was seen not;

Whether sinking as the rain sinks,

Whether rising as the mists rise,

Hiawatha saw not, knew not,

Only saw that he had vanished,

Leaving him alone and fainting,

With the misty lake below him,

And the reeling stars above him.

On the morrow and the next day,

When the sun through heaven descending,

Like a red and burning cinder

From the hearth of the Great Spirit,

Fell into the western waters,

Came Mondamin for the trial,

For the strife with Hiawatha;

Came as silent as the dew comes,

From the empty air appearing,

Into empty air returning,

Taking shape when earth it touches

But invisible to all men

In its coming and its going.

Thrice they wrestled there together

In the glory of the sunset,

Till the darkness fell around them,

Till the heron, the Shuh-shuh-gah,

From her haunts among the fen-lands,

Uttered her loud cry of famine,

And Mondamin paused to listen.

Tall and beautiful he stood there,

In his garments green and yellow;

To and fro his plumes above him

Waved and nodded with his breathing,

And the sweat of the encounter

Stood like drops of dew upon him.

And he cried, “O Hiawatha!

Bravely have you wrestled with me,

Thrice have wrestled stoutly with me,

And the Master of Life, who sees us,

He will give to you the triumph!”

Then he smiled and said: “To-morrow

Is the last day of your conflict,

Is the last day of your fasting.

You will conquer and o’ercome me;

Make a bed for me to lie in,

Where the rain may fall upon me,

Where the sun may come and warm me;

Strip these garments, green and yellow,

Strip this nodding plumage from me,

Lay me in the earth and make it

Soft and loose and light above me.

“Let no hand disturb my slumber,

Let no weed nor worm molest me,

Let not Kahgahgee, the raven,

Come to haunt me and molest me,

Only come yourself to watch me,

Till I wake, and start, and quicken,

Till I leap into the sunshine.”

And thus saying, he departed;

Peacefully slept Hiawatha,

But he heard the Wawonaissa,

Heard the whippoorwill complaining,

Perched upon his lonely wigwam;

Heard the rushing Sebowisha,

Heard the rivulet rippling near him,

Talking to the darksome forest;

Heard the sighing of the branches,

As they lifted and subsided

At the passing of the night-wind,

Heard them, as one hears in slumber

Far-off murmurs, dreamy whispers:

Peacefully slept Hiawatha.

On the morrow came Nokomis,

On the seventh day of his fasting,

Came with food for Hiawatha,

Came imploring and bewailing,

Lest his hunger should o’ercome him,

Lest his fasting should be fatal.

But he tasted not, and touched not,

Only said to her, “Nokomis,

Wait until the sun is setting,

Till the darkness falls around us,

Till the heron, the Shuh-shuh-gah,

Crying from the desolate marshes,

Tells us that the day is ended.”

Homeward weeping went Nokomis,

Sorrowing for her Hiawatha,

Fearing lest his strength should fail him,

Lest his fasting should be fatal.

He meanwhile sat weary waiting

For the coming of Mondamin,

Till the shadows, pointing eastward,

Lengthened over field and forest,

Till the sun dropped from the heaven,

Floating on the waters westward,

As a red leaf in the Autumn

Falls and floats upon the water,

Falls and sinks into its bosom.

And behold! the young Mondamin,

With his soft and shining tresses,

With his garments green and yellow,

With his long and glossy plumage,

Stood and beckoned at the doorway.

And as one in slumber walking,

Pale and haggard, but undaunted,

From the wigwam Hiawatha

Came and wrestled with Mondamin.

Round about him spun the landscape,

Sky and forest reeled together,

And his strong heart leaped within him,

As the sturgeon leaps and struggles

In a net to break its meshes.

Like a ring of fire around him

Blazed and flared the red horizon,

And a hundred suns seemed looking

At the combat of the wrestlers.

Suddenly upon the greensward

All alone stood Hiawatha,

Panting with his wild exertion,

Palpitating with the struggle;

And before him, breathless, lifeless,

Lay the youth, with hair dishevelled,

Plumage torn, and garments tattered,

Dead he lay there in the sunset.

And victorious Hiawatha

Made the grave as he commanded,

Stripped the garments from Mondamin,

Stripped his tattered plumage from him,

Laid him in the earth, and made it

Soft and loose and light above him;

And the heron, the Shuh-shuh-gah,

From the melancholy moorlands,

Gave a cry of lamentation,

Gave a cry of pain and anguish!

Homeward then went Hiawatha

To the lodge of old Nokomis,

And the seven days of his fasting

Were accomplished and completed.

But the place was not forgotten

Where he wrestled with Mondamin;

Nor forgotten nor neglected

Was the grave where lay Mondamin,

Sleeping in the rain and sunshine,

Where his scattered plumes and garments

Faded in the rain and sunshine.

Day by day did Hiawatha

Go to wait and watch beside it;

Kept the dark mould soft above it,

Kept it clean from weeds and insects,

Drove away, with scoffs and shoutings,

Kahgahgee, the king of ravens.

Till at length a small green feather

From the earth shot slowly upward,

Then another and another,

And before the Summer ended

Stood the maize in all its beauty,

With its shining robes about it,

And its long, soft, yellow tresses;

And in rapture Hiawatha

Cried aloud, “It is Mondamin!

Yes, the friend of man, Mondamin!”

Then he called to old Nokomis

And Iagoo, the great boaster,

Showed them where the maize was growing,

Told them of his wondrous vision,

Of his wrestling and his triumph,

Of this new gift to the nations,

Which should be their food forever.

And still later, when the Autumn

Changed the long, green leaves to yellow,

And the soft and juicy kernels

Grew like wampum hard and yellow,

Then the ripened ears he gathered,

Stripped the withered husks from off them,

As he once had stripped the wrestler,

Gave the first Feast of Mondamin,

And made known unto the people

This new gift of the Great Spirit.

VII.

HIAWATHA’S SAILING

Of your yellow bark, O Birch-Tree!

Growing by the rushing river,

Tall and stately in the valley!

I a light canoe will build me,

Build a swift Cheemaun for sailing,

That shall float upon the river,

Like a yellow leaf in Autumn,

Like a yellow water-lily!

“Lay aside your cloak, O Birch-Tree!

Lay aside your white-skin wrapper,

For the summer-time is coming,

And the sun is warm in heaven,

And you need no white-skin wrapper!”

Thus aloud cried Hiawatha

In the solitary forest,

By the rushing Taquamenaw,

When the birds were singing gayly,

In the Moon of Leaves were singing,

And the sun, from sleep awaking,

Started up and said, “Behold me!

Gheezis, the great Sun, behold me!”

And the tree with all its branches

Rustled in the breeze of morning,

Saying, with a sigh of patience,

“Take my cloak, O Hiawatha!”

With his knife the tree he girdled;

Just beneath its lowest branches,

Just above the roots, he cut it,

Till the sap came oozing outward;

Down the trunk, from top to bottom,

Sheer he cleft the bark asunder,

With a wooden wedge he raised it,

Stripped it from the trunk unbroken.

“Give me of your boughs, O Cedar!

Of your strong and pliant branches,

My canoe to make more steady,

Make more strong and firm beneath me!”

Through the summit of the Cedar

Went a sound, a cry of horror,

Went a murmur of resistance;

But it whispered, bending downward,

“Take my boughs, O Hiawatha!”

Down he hewed the boughs of cedar,

Shaped them straightway to a framework,

Like two bows he formed and shaped them,

Like two bended bows together.

“Give me of your roots, O Tamarack!

Of your fibrous roots, O Larch-Tree!

My canoe to bind together,

So to bind the ends together

That the water may not enter,

That the river may not wet me!”

And the Larch, with all its fibres,

55Shivered in the air of morning,

Touched his forehead with its tassels,

Said, with one long sigh of sorrow,

“Take them all, O Hiawatha!”

From the earth he tore the fibres,

Tore the tough roots of the Larch-Tree,

Closely sewed the bark together,

Bound it closely to the framework.

“Give me of your balm, O Fir-Tree!

Of your balsam and your resin,

So to close the seams together

That the water may not enter,

That the river may not wet me!”

And the Fir-Tree, tall and sombre,

Sobbed through all its robes of darkness,

Rattled like a shore with pebbles,

Answered wailing, answered weeping,

“Take my balm, O Hiawatha!”

And he took the tears of balsam,

Took the resin of the Fir-Tree,

Smeared therewith each seam and fissure,

Made each crevice safe from water.

“Give me of your quills, O Hedgehog!

All your quills, O Kagh, the Hedgehog!

I will make a necklace of them,

Make a girdle for my beauty,

And two stars to deck her bosom!”

From a hollow tree the Hedgehog

With his sleepy eyes looked at him,

Shot his shining quills, like arrows,

Saying, with a drowsy murmur,

Through the tangle of his whiskers,

“Take my quills, O Hiawatha!”

From the ground the quills he gathered,

All the little shining arrows,

Stained them red and blue and yellow,

With the juice of roots and berries;

Into his canoe he wrought them,

Round its waist a shining girdle,

Round its bows a gleaming necklace,

On its breast two stars resplendent.

In the valley by the river,

In the bosom of the forest;

And the forest’s life was in it.

In the valley, by the river,

In the bosom of the forest;

And the forest’s life was in it,

All its mystery and its magic,

All the lightness of the birch-tree,

All the toughness of the cedar,

All the larch’s supple sinews;

And it floated on the river,

Like a yellow leaf in Autumn,

Like a yellow water-lily.

Down the rushing Taquamenaw,

Sailed through all its bends and windings.”

Paddles none he had or needed,

For his thoughts as paddles served him,

And his wishes served to guide him;

Swift or slow at will he glided,

Veered to right or left at pleasure.

Then he called aloud to Kwasind,

To his friend, the strong man, Kwasind,

Saying, “Help me clear this river

Of its sunken logs and sand-bars,”

Straight into the river Kwasind

Plunged as if he were an otter,

Dived as if he were a beaver,

Stood up to his waist in water,

To his arm-pits in the river,

Swam and shouted in the river,

Tugged at sunken logs and branches,

With his hands he scooped the sand-bars,

With his feet the ooze and tangle.

And thus sailed my Hiawatha

Down the rushing Taquamenaw,

Sailed through all its bends and windings,

Sailed through all its deeps and shallows,

While his friend, the strong man, Kwasind,

Swam the deeps, the shallows waded.

Up and down the river went they,

In and out among its islands,

Cleared its bed of root and sand-bar,

Dragged the dead trees from its channel,

Made its passage safe and certain,

Made a pathway for the people,

From its springs among the mountains,

To the waters of Pauwating,

To the bay of Taquamenaw.

XXI.

THE WHITE MAN’S FOOT.

Close beside a frozen river,

Sat an old man, sad and lonely.

White his hair was as a snow-drift;

Dull and low his fire was burning,

And the old man shook and trembled,

Folded in his Waubewyon,

In his tattered white-skin-wrapper,

Hearing nothing but the tempest

As it roared along the forest,

Seeing nothing but the snow-storm,

As it whirled and hissed and drifted.

All the coals were white with ashes,

And the fire was slowly dying,

As a young man, walking lightly,

At the open doorway entered.

Red with blood of youth his cheeks were,

Soft his eyes, as stars in Spring-time,

Bound his forehead was with grasses,

Bound and plumed with scented grasses;

On his lips a smile of beauty,

Filling all the lodge with sunshine,

In his hand a bunch of blossoms

Filling all the lodge with sweetness.

“Ah, my son!” exclaimed the old man,

“Happy are my eyes to see you.

Sit here on the mat beside me,

Sit here by the dying embers,

Let us pass the night together.

Tell me of your strange adventures,

Of the lands where you have travelled;

I will tell you of my prowess,

Of my many deeds of wonder.”

From his pouch he drew his peace-pipe,

Very old and strangely fashioned;

Made of red stone was the pipe-head,

And the stem a reed with feathers;

Filled the pipe with bark of willow,

Placed a burning coal upon it,

Gave it to his guest, the stranger,

And began to speak in this wise:

“When I blow my breath about me,

When I breathe upon the landscape,

Motionless are all the rivers,

Hard as stone becomes the water!”

And the young man answered, smiling:

“When I blow my breath about me,

When I breathe upon the landscape,

Flowers spring up o’er all the meadows,

Singing, onward rush the rivers!”

“When I shake my hoary tresses,”

Said the old man, darkly frowning,

“All the land with snow is covered;

All the leaves from all the branches

Fall and fade and die and wither,

For I breathe, and lo! they are not.

From the waters and the marshes

Rise the wild goose and the heron,

Fly away to distant regions,

For I speak, and lo! they are not.

And where’er my footsteps wander,

All the wild beasts of the forest

Hide themselves in holes and caverns,

And the earth becomes as flintstone!”

“When I shake my flowing ringlets,”

Said the young man, softly laughing,

“Showers of rain fall warm and welcome,

Plants lift up their heads rejoicing,

Back unto their lakes and marshes

Come the wild goose and the heron,

Homeward shoots the arrowy swallow,

Sing the bluebird and the robin,

And where’er my footsteps wander,

All the meadows wave with blossoms,

All the woodlands ring with music,

All the trees are dark with foliage!”

While they spake, the night departed:

From the distant realms of Wabun,

From his shining lodge of silver,

Like a warrior robed and painted,

Came the sun, and said, “Behold me!

Gheezis, the great sun, behold me!”

Then the old man’s tongue was speechless

And the air grew warm and pleasant,

And upon the wigwam sweetly

Sang the bluebird and the robin,

And the stream began to murmur,

And a scent of growing grasses

Through the lodge was gently wafted.

And Segwun, the youthful stranger,

More distinctly in the daylight

Saw the icy face before him;

It was Peboan, the Winter!

From his eyes the tears were flowing,

As from melting lakes the streamlets,

And his body shrunk and dwindled

As the shouting sun ascended,

Till into the air it faded,

Till into the ground it vanished,

And the young man saw before him,

On the hearth-stone of the wigwam,

Where the fire had smoked and smouldered,

Saw the earliest flower of Spring-time,

Saw the Beauty of the Spring-time,

Saw the Miskodeed in blossom.

Thus it was that in the North-land

After that unheard-of coldness,

That intolerable Winter,

Came the Spring with all its splendor,

All its birds and all its blossoms,

All its flowers and leaves and grasses.

Sailing on the wind to northward,

Flying in great flocks, like arrows,

Like huge arrows shot through heaven,

Passed the swan, the Mahnahbezee,

Speaking almost as a man speaks;

And in long lines waving, bending

Like a bow-string snapped asunder,

Came the white goose, Waw-be-wawa;

And in pairs, or singly flying,

Mahng the loon, with clangorous pinions,

The blue heron, the Shuh-shuh-gah,

And the grouse, the Mushkodasa.

In the thickets and the meadows

Piped the bluebird, the Owaissa,

On the summit of the lodges

Sang the Opechee, the robin,

In the covert of the pine-trees

Cooed the pigeon, the Omemee,

And the sorrowing Hiawatha,

Speechless in his infinite sorrow,

Heard their voices calling to him,

Went forth from his gloomy doorway,

Stood and gazed into the heaven,

Gazed upon the earth and waters.

From the regions of the morning,

From the shining land of Wabun,

Homeward now returned Iagoo,

The great traveller, the great boaster,

Full of new and strange adventures,

Marvels many and many wonders.

And the people of the village

Listened to him as he told them

Of his marvellous adventures,

Laughing answered him in this wise:

“Ugh! it is indeed Iagoo!

No one else beholds such wonders!”

He had seen, he said, a water

Bigger than the Big-Sea-Water,

Broader than the Gitche Gumee,

Bitter so that none could drink it!

At each other looked the warriors,

Looked the women at each other,

Smiled, and said, “It cannot be so!

Kaw!” they said, “it cannot be so!”

O’er it, said he, o’er this water

Came a great canoe with pinions,

A canoe with wings came flying,

Bigger than a grove of pine-trees,

Taller than the tallest tree-tops!

And the old men and the women

Looked and tittered at each other;

“Kaw!” they said, “we don’t believe it!”

From its mouth, he said, to greet him,

Came Waywassimo, the lightning,

Came the thunder, Annemeekee!

And the warriors and the women

Laughed aloud at poor Iagoo;

“Kaw!” they said, “what tales you tell us!”

In it, said he, came a people,

In the great canoe with pinions

Came, he said, a hundred warriors;

Painted white were all their faces,

And with hair their chins were covered!

And the warriors and the women

Laughed and shouted in derision,

Like the ravens on the tree-tops,

Like the crows upon the hemlocks.

“Kaw!” they said, “what lies you tell us!

Do not think that we believe them!”

Restless, struggling, toiling, striving

Rushed their great canoes of thunder.

But he gravely spake and answered

To their jeering and their jesting:

“True is all Iagoo tells us;

I have seen it in a vision,

Seen the great canoe with pinions,

Seen the people with white faces,

Seen the coming of this bearded

People of the wooden vessel

From the regions of the morning,

From the shining land of Wabun.

“Gitche Manito the Mighty,

The Great Spirit, the Creator,

Sends them hither on his errand,

Sends them to us with his message.

Wheresoe’er they move, before them

Swarms the stinging fly, the Ahmo,

Swarms the bee, the honey-maker;

Wheresoe’er they tread, beneath them

Springs a flower unknown among us,

Springs the White-man’s Foot in blossom.

“Let us welcome, then, the strangers,

Hail them as our friends and brothers,

And the heart’s right hand of friendship

Give them when they come to see us.

Gitche Manito, the Mighty,

Said this to me in my vision.

“I beheld, too, in that vision

All the secrets of the future,

Of the distant days that shall be.

I beheld the westward marches

Of the unknown, crowded nations.

All the land was full of people,

Restless, struggling, toiling, striving,

Speaking many tongues, yet feeling

But one heart-beat in their bosoms.

In the woodlands rang their axes,

Smoked their towns in all the valleys,

Rushed their great canoes of thunder.

“Then a darker, drearier vision

Passed before me, vague and cloud-like:

I beheld our nation scattered,

All forgetful of my counsels,

Weakened, warring with each other;

Saw the remnants of our people

Sweeping westward, wild and woful,

Like the cloud-rack of a tempest,

Like the withered leaves of Autumn!”

XXII.

HIAWATHA’S DEPARTURE.

By the shining Big-Sea-Water,

At the doorway of his wigwam,

In the pleasant summer morning,

Hiawatha stood and waited.

All the air was full of freshness,

All the earth was bright and joyous,

And before him, through the sunshine,

Westward toward the neighboring forest

Passed in golden swarms the Ahmo,

Passed the bees, the honey-makers,

Burning, singing in the sunshine.

Bright above him shone the heavens,

Level spread the lake before him;

From its bosom leaped the sturgeon,

Sparkling, flashing in the sunshine;

On its margin the great forest

Stood reflected in the water,

Every tree-top had its shadow,

Motionless beneath the water.

From the brow of Hiawatha

Gone was every trace of sorrow,

As the fog from off the water,

As the mist from off the meadow.

With a smile of joy and triumph,

With a look of exultation,

As of one who in a vision

Sees what is to be, but is not,

Stood and waited Hiawatha.

Toward the sun his hands were lifted,

Both the palms spread out against it,

And between the parted fingers

Fell the sunshine on his features,

Flecked with light his naked shoulders,

As it falls and flecks an oak-tree

Through the rifted leaves and branches.

O’er the water floating, flying,

Something in the hazy distance,

Something in the mists of morning,

Loomed and lifted from the water,

Now seemed floating, now seemed flying,

Coming nearer, nearer, nearer.

Was it Shingebis the diver?

Was it the pelican, the Shada?

Or the heron, the Shuh-shuh-gah?

Or the white goose, Waw-be-wawa,

With the water dripping, flashing

From its glossy neck and feathers?

It was neither goose nor diver,

Neither pelican nor heron,

O’er the water, floating, flying,

Through the shining mist of morning,

But a birch canoe with paddles,

Rising, sinking on the water,

Dripping, flashing in the sunshine;

And within it came a people

From the distant land of Wabun,

From the farthest realms of morning

Came the Black-Robe chief, the Prophet,

He the Priest of Prayer, the Pale-face,

With his guides and his companions.

And the noble Hiawatha,

With his hands aloft extended,

Held aloft in sign of welcome,

Waited, full of exultation,

Till the birch canoe with paddles

Grated on the shining pebbles,

Stranded on the sandy margin,

Till the Black-Robe chief, the Pale-face,

With the cross upon his bosom,

Landed on the sandy margin.

Then the joyous Hiawatha

Cried aloud and spake in this wise:

“Beautiful is the sun, O strangers,

When you come so far to see us!

All our town in peace awaits you;

All our doors stand open for you;

You shall enter all our wigwams,

For the heart’s right hand we give you.

“Never bloomed the earth so gayly,

Never shone the sun so brightly,

As to-day they shine and blossom

When you come so far to see us!

Never was our lake so tranquil,

Nor so free from rocks and sand-bars;

For your birch canoe in passing

Has removed both rock and sand-bar.

“Never before had our tobacco

Such a sweet and pleasant flavor,

Never the broad leaves of our corn-fields

Were so beautiful to look on,

As they seem to us this morning,

When you come so far to see us!”

And the Black-Robe chief made answer,

Stammered in his speech a little,

Speaking words yet unfamiliar:

“Peace be with you, Hiawatha,

Peace be with you and your people,

Peace of prayer, and peace of pardon,

Peace of Christ, and joy of Mary!”

Then the generous Hiawatha

Led the strangers to his wigwam,

Seated them on skins of bison,

Seated them on skins of ermine,

And the careful old Nokomis

Brought them food in bowls of bass-wood,

Water brought in birchen dippers,

And the calumet, the peace-pipe,

Filled and lighted for their smoking.

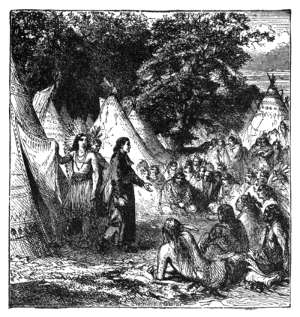

NAVAJO MATRON WEAVING A BLANKET.

Heart and hand that move together.”

Cried aloud and spoke on this wise:

For the heart’s right hand we give you”

All the warriors of the nation,

All the Jossakeeds, the prophets,

The magicians, the Wabenos,

And the medicine-men, the Medas,

Came to bid the strangers welcome;

“It is well,” they said, “O brothers,

That you come so far to see us;”

In a circle round the doorway,

With their pipes they sat in silence,

Waiting to behold the strangers,

Waiting to receive their message;

Till the Black-Robe chief, the Pale-face,

From the wigwam came to greet them,

Stammering in his speech a little,

Speaking words yet unfamiliar;

“It is well,” they said, “O brother,

That you come so far to see us!”

Then the Black-Robe chief, the prophet,

Told his message to the people,

Told the purport of his mission,

Told them of the Virgin Mary,

And her blessed Son, the Saviour,

How in distant lands and ages

He had lived on earth as we do;

How he fasted, prayed, and labored;

How the Jews, the tribe accursed,

Mocked him, scourged him, crucified him;

How he rose from where they laid him,

Walked again with his disciples,

And ascended into heaven.

And the chiefs made answer, saying:

“We have listened to your message,

We have heard your words of wisdom,

We will think on what you tell us.

It is well for us, O brothers,

That you come so far to see us!”

Then they rose up and departed

Each one homeward to his wigwam,

To the young men and the women

Told the story of the strangers

Whom the Master of Life had sent them

From the shining land of Wabun.

Grew the afternoon of Summer,

With a drowsy sound the forest

Whispered round the sultry wigwam,

With a sound of sleep the water

Rippled on the beach below it;

From the corn-fields shrill and ceaseless

Sang the grasshopper, Pah-puk-keena;

And the guests of Hiawatha,

Weary with the heat of Summer,

Slumbered in the sultry wigwam.

Slowly o’er the simmering landscape

Fell the evening’s dusk and coolness,

And the long and level sunbeams

Shot their spears into the forest,

Breaking through its shields of shadow,

Rushed into each secret ambush,

Searched each thicket, dingle, hollow;

Still the guests of Hiawatha

Slumbered in the silent wigwam.

From his place rose Hiawatha,

Bade farewell to old Nokomis,

Spake in whispers, spake in this wise,

Did not wake the guests, that slumbered:

“I am going, O Nokomis,

On a long and distant journey,

To the portals of the Sunset,

To the regions of the home-wind,

Of the Northwest wind, Keewaydin.

But these guests I leave behind me,

In your watch and ward I leave them;

See that never harm comes near them,

See that never fear molests them,

Never danger nor suspicion,

Never want of food or shelter,

In the lodge of Hiawatha!”

Forth into the village went he,

Bade farewell to all the warriors,

Bade farewell to all the young men,

Spake persuading, spake in this wise:

“I am going, O my people,

On a long and distant journey;

Many moons and many winters

Will have come, and will have vanished,

Ere I come again to see you.

But my guests I leave behind me;

Listen to their words of wisdom,

Listen to the truth they tell you,

For the Master of Life has sent them

From the land of light and morning!”

On the shore stood Hiawatha,

Turned and waved his hand at parting;

On the clear and luminous water

Launched his birch canoe for sailing,

From the pebbles of the margin

Shoved it forth into the water;

Whispered to it, “Westward! westward!”

And with speed it darted forward.

And the evening sun descending

Set the clouds on fire with redness,

Burned the broad sky, like a prairie,

Left upon the level water

One long track and trail of splendor,

Down whose stream, as down a river,

Westward, westward Hiawatha

Sailed into the fiery sunset,

Sailed into the purple vapors,

Sailed into the dusk of evening.

And the people from the margin

Watched him floating, rising, sinking,

Till the birch canoe seemed lifted

High into that sea of splendor,

Till it sank into the vapors

Like the new moon slowly, slowly

Sinking in the purple distance.

And they said, “Farewell forever!”

Said, “Farewell, O Hiawatha!”

And the forests, dark and lonely,

Moved through all their depths of darkness,

Sighed, “Farewell, O Hiawatha!”

And the waves upon the margin

Rising, rippling on the pebbles,

Sobbed, “Farewell, O Hiawatha!”

And the heron, the Shuh-shuh-gah,

From her haunts among the fen-lands,

Screamed, “Farewell, O Hiawatha!”

Thus departed Hiawatha,

Hiawatha the Beloved,

In the glory of the sunset,

In the purple mists of evening,

To the regions of the home-wind,

Of the Northwest wind, Keewaydin,

To the Islands of the Blessed,

To the kingdom of Ponemah,

To the land of the Hereafter!

questions to consider

- What emotions does the poem create, and how does Longfellow’s use of language, symbols, sentence structures – the tools of writing – help to create those emotions?

- What characteristics of the poem place it as an example of American Romanticism?

Candela Citations

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Hiawatha. Authored by: Susan Oaks. Project: American Literature 1600-1865. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Introduction text and image from Becoming America. Authored by: Wendy Kurant. Provided by: University of North Georgia. Located at: https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Literature_and_Literacy/Book%3A_Becoming_America_-_An_Exploration_of_American_Literature_from_Precolonial_to_Post-Revolution/04%3A_Nineteenth_Century_Romanticism_and_Transcendentalism/4.13%3A_Henry_Wadsworth_Longfellow_(1807%E2%80%931882). Project: Becoming America - An Exploration of American Literature from Precolonial to Post-Revolution, sourced from GALILEO Open Learning Materials. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Song of Hiawatha. Authored by: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Provided by: Project Gutenberg. Located at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/30795/30795-h/30795-h.htm#XXI. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright