Learning outcomes

- Understand the social and interpersonal impacts of divorce

- Describe the social and interpersonal impact of family abuse

- Explain how financial status impacts marital stability. What other factors are associated with a couple’s financial status?

- Why do you think divorced males are more likely to remarry and to do so more quickly than their female counterparts?

- Describe the social and interpersonal impact of family abuse

- Explain why more than half of IPV goes unreported.

- Discuss why many CPS cases are not labeled as victims.

As the structure of family changes over time, so do the challenges families face. Events like divorce and remarriage present new difficulties for families and individuals. Other long-standing domestic issues such as abuse continue to strain the health and stability of today’s families.

Divorce and Remarriage

As the structure of family changes over time, so do the challenges families face. Events like divorce and remarriage present new difficulties for families and individuals. Other long-standing domestic issues such as abuse continue to strain the health and stability of today’s families.

Divorce

Divorce, while fairly common and accepted in modern U.S. society, was once a word that would only be whispered and was accompanied by gestures of disapproval. In 1960, divorce was generally uncommon, affecting only 9.1 out of every 1,000 married persons. That number more than doubled (to 20.3) by 1975 and peaked in 1980 at 22.6 (Popenoe, 2007). Over the last quarter century, divorce rates have dropped steadily and are now similar to those in 1970. The dramatic increase in divorce rates after the 1960s has been associated with the liberalization of divorce laws and the shift in societal make up due to women increasingly entering the workforce (Michael, 1978). The decrease in divorce rates can be attributed to two probable factors: an increase in the age at which people get married, and an increased level of education among those who marry—both of which have been found to promote greater marital stability.

Divorce does not occur equally among all people in the United States; some segments of the U.S. population are more likely to divorce than others. According the American Community Survey (ACS), men and women in the Northeast have the lowest rates of divorce at 7.2 and 7.5 per 1,000 people. The South has the highest rate of divorce at 10.2 for men and 11.1 for women. Divorce rates are likely higher in the South because marriage rates are higher and marriage occurs at younger-than-average ages in this region. In the Northeast, the marriage rate is lower and first marriages tend to be delayed; therefore, the divorce rate is lower (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). More specifically, our nation’s capital, Washington D.C. has the highest rates of divorce with a rate of 29.9 per 1,000 in 2015 and Hawaii and the lowest with 11.1 percent per 1,000 [1]

The rate of divorce also varies by race. In a 2009 ACS study, American Indian and Alaskan Natives reported the highest percentages of currently divorced individuals (12.6 percent) followed by blacks (11.5 percent), whites (10.8 percent), Pacific Islanders (8 percent), Latinos (7.8 percent) and Asians (4.9 percent) (ACS, 2011). In general those who marry at a later age, have a college education have lower rates of divorce.

So what causes divorce? While more young people are choosing to postpone or opt out of marriage, those who enter into the union do so with the expectation that it will last. A great deal of marital problems can be related to stress, especially financial stress. According to researchers participating in the University of Virginia’s National Marriage Project, couples who enter marriage without a strong asset base (like a home, savings, and a retirement plan) are 70 percent more likely to be divorced after three years than are couples with at least $10,000 in assets. This is connected to factors such as age and education level that correlate with low incomes.

The addition of children to a marriage creates added financial and emotional stress. Research has established that marriages enter their most stressful phase upon the birth of the first child (Popenoe and Whitehead, 2007). This is particularly true for couples who have multiples (twins, triplets, and so on). Married couples with twins or triplets are 17 percent more likely to divorce than those with children from single births (McKay, 2010). Another contributor to the likelihood of divorce is a general decline in marital satisfaction over time. As people get older, they may find that their values and life goals no longer match up with those of their spouse (Popenoe and Whitehead, 2004).

Figure 1. A study from Radford University indicated that bartenders are among the professions with the highest divorce rates (38.4 percent). Other traditionally low-wage industries (like restaurant service, custodial employment, and factory work) are also associated with higher divorce rates. (Aamodt and McCoy, 2010). (Photo courtesy of Daniel Lobo/flickr)

Remarriage

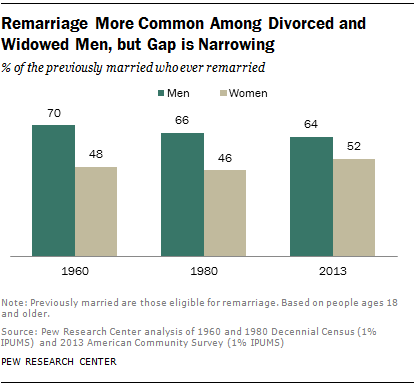

In 2013, 23 percent of married people had been married before,[2] compared with just 13 percent in 1960. In 2013, 4 out of 10 new marriages included at least one partner who had been previously married and half of these (2 out of 10) include two spouses who were remarrying (Geiger and Livingston, 2019). Previously married men are more likely to get married again, with 64 percent getting married twice compared to 52 percent of women, but this could be an indication of desire—54 percent of women say they do not want to remarry as opposed to 30 percent of men (Geiger and Livingston, 2019).

People in a second marriage account for approximately 19.3 percent of all married persons, and those who have been married three or more times account for 5.2 percent (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). The vast majority (91 percent) of remarriages occur after divorce; only 9 percent occur after death of a spouse (Kreider, 2006). Most men and women remarry within five years of a divorce, with the median length for men (three years) being lower than for women (4.4 years). This length of time has been fairly consistent since the 1950s. The majority of those who remarry are between the ages of twenty-five and forty-four (Kreider, 2006). The general pattern of remarriage also shows that whites are more likely to remarry than Hispanics, Blacks, or Asians.

Figure 2. Men are more likely than women to get remarried after divorce.

Marriage the second time around (or third or fourth) can be a very different process than the first. Remarriage lacks many of the classic courtship rituals of a first marriage. In a second marriage, individuals are less likely to deal with issues like parental approval, premarital sex, or desired family size (Elliot, 2010). In a survey of households formed by remarriage, a mere 8 percent included only biological children of the remarried couple. Of the 49 percent of homes that include children, 24 percent included only the woman’s biological children, 3 percent included only the man’s biological children, and 9 percent included a combination of both spouse’s children (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006).

Figure 3. Whites are more likely than other racial and ethnic groups to get remarried.

Children of Divorce and Remarriage

Divorce and remarriage can be stressful on partners and children alike. Divorce is often justified by the notion that children are better off in a divorced family than in a family with parents who do not get along, but many other variables are important specifically parental involvement of the non-custodial parent and the socioeconomic status of the custodial parent.

Children’s ability to deal with a divorce may depend on their age. Research has found that divorce may be most difficult for school-aged children, as they are old enough to understand the separation but not old enough to understand the reasoning behind it. Older teenagers are more likely to recognize the conflict that led to the divorce but may still feel fear, loneliness, guilt, and pressure to choose sides. Infants and preschool-age children may suffer the heaviest impact from the loss of routine that the marriage offered (Temke, 2006).

Proximity to parents also makes a difference in a child’s well-being after divorce. Boys who live or have joint arrangements with their fathers show less aggression than those who are raised by their mothers only. Similarly, girls who live or have joint arrangements with their mothers tend to be more responsible and mature than those who are raised by their fathers only. Nearly three-fourths of the children of parents who are divorced live in a household headed by their mother, leaving many boys without a father figure residing in the home (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011b). Still, researchers suggest that a strong parent-child relationship can greatly improve a child’s adjustment to divorce (Temke, 2006).

Families and inequality

Sociologist Annette Lareau studied class differences in family life by closely following 88 families from various socioeconomic backgrounds. She found middle-class parents to more involved in their children’s education, but not because lower-class parents were disinterested in their children’s learning. Both wanted the best for their children, but Lareau found that parents approached education and family life in different ways.

On the whole, middle-class parents were more likely to spend time investing in their children’s education while at home and through various extracurricular activities, whereas many of the lower-class parents viewed the schools as specialists and teachers as experts who had the primary responsibility for educating their children. Also due to time and monetary constraints, lower-class children had more unstructured time and autonomy, which also led to greater creativity. Middle-class parents were more likely to read and talk with their kids, be involved in their schoolwork, and supplement their school education.[3]

In her 2003 book, Unequal Childhoods, Lareau used the terms concerted cultivation and accomplishment of natural growth to describe the differences in parenting styles. Each parenting style is described below:

- Concerted Cultivation: The parenting style, favored by middle-class families, in which parents encourage negotiation and discussion and the questioning of authority, and enroll their children in extensive organized activity participation. This style helps children in middle-class careers, teaches them to question people in authority, develops a large vocabulary, and makes them comfortable in discussions with people of authority. However, it gives the children a sense of entitlement.

- Accomplishment of Natural Growth: The parenting style, favored by working-class and lower-class families, in which parents issue directives to their children rather than negotiations, encourage the following and trusting of people in authority positions, and do not structure their children’s daily activities, but rather let the children play on their own. This method has benefits that prepare the children for a job in the “working” or “poor-class” jobs, teaches the children to respect and take the advice of people in authority, and allows the children to become independent at a younger age.

Figure 4. Thirty percent of women who are murdered are killed by their intimate partner. What does this statistic reveal about societal patterns and norms concerning intimate relationships and gender roles? (Photo courtesy of Kathy Kimpel/flickr)

Domestic Violence

Domestic violence is a significant social problem in the United States. It is often characterized as violence between household or family members, specifically spouses. To include unmarried, cohabitating, and same-sex couples, family sociologists have created the term intimate partner violence (IPV). According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, nearly 20 people per minute are physically abused by an intimate partner in the United States. During one year, this equates to more than 10 million women and men. Women are the primary victims of intimate partner violence. It is estimated that one in four women has experienced some form of IPV in her lifetime (compared to one in seven men) (Catalano, 2007).

IPV may include physical violence, such as punching, kicking, or other methods of inflicting physical pain; sexual violence, such as rape or other forced sexual acts; threats and intimidation that imply either physical or sexual abuse; and emotional abuse, such as harming another’s sense of self-worth through words or controlling another’s behavior. IPV often starts as emotional abuse and then escalates to other forms or combinations of abuse. About 1 in 4 women and 1 in 10 men experienced contact sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner and reported an IPV-related impact during their lifetime (Centers for Disease Control, 2018).

According to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, IPV affects different segments of the population at different rates with American Indian and Alaskan Native women experiences the highest levels of IPV at 48 percent compared to 47 percent among multiracial women, 45 percent for black women, 37 percent for white women, 34 percent for Latinas, and 18 percent Asian/Pacific Islander women. Contact sexual violence, which includes rape and unwanted sexual contact, is experienced by 42.6 percent of women and 24.8 percent of men in the U.S. (Centers for Disease Control, 2018). Bisexual women are most likely (61 percent) to experience rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner compared to 44 percent of lesbians, 37 percent of bisexual men, 35 percent of heterosexual women, 29 percent of heterosexual men, and 26 percent of gay men.

Link to Learning

For visual representations of this survey data, please see the link at the Intimate Partner Violence Fact Sheet.

Accurate statistics on IPV are difficult to determine, as it is estimated that more than half of nonfatal IPV goes unreported. It is not until victims choose to report crimes that patterns of abuse are exposed. People who have the most to lose by reporting domestic violence, such as women who are in arranged marriages, lack U.S. citizenship, and/or are homeless or involved with the criminal justice system, are likely the most undercounted in these victimization surveys.

Sometimes abuse is reported to police by a third party, but it still may not be confirmed by victims. A study of domestic violence incident reports found that even when confronted by police about abuse, 29 percent of victims denied that abuse occurred. Surprisingly, 19 percent of their assailants were likely to admit to abuse (Felson, Ackerman, and Gallagher, 2005). According to the National Criminal Victims Survey, victims cite varied reason why they are reluctant to report abuse, as shown in the table below.

This chart shows reasons that victims give for why they fail to report abuse to police authorities (Catalano, 2007).

| Reason Abuse Is Unreported | % Females | % Males |

|---|---|---|

| Considered a Private Matter | 22 | 39 |

| Fear of Retaliation | 12 | 5 |

| To Protect the Abuser | 14 | 16 |

| Belief That Police Won’t Do Anything | 8 | 8 |

Why Does She Stay?

In the video below, Leslie Morgan Steiner tells her story of experiencing severe domestic violence as a young woman. Listen carefully as she describes the stages of domestic violence. What are the early signs?

After watching the TED Talk, do you have an answer to the question, “Why does she stay?”

What does a typical domestic violence survivor look like? What can you do to end domestic violence according to Steiner?

Child Abuse

In the fiscal year 2017, approximately 4.3 million children are the subjects of Child Protective Services (CPS) Reports and this number includes duplicates (more than one report for the same child) and the majority (65.7 percent) of these reports were made by professionals such as educational personnel (19.4 percent), legal and law enforcement personnel (18.3 percent), and social services personnel (11.7 percent) [4]. Of these, 17 percent or 674,000 are classified as victims, with 74.9 percent of victims described as neglected, 18.3 percent as physically abused, and 8.6 percent as sexually abused. These victims may suffer a single maltreatment type or a combination of two or more maltreatment types. An estimated 1,720 children died of abuse and neglect at a rate of 2.32 per 100,000 children in the national population.

Infants are also often victims of physical abuse, particularly in the form of violent shaking. This type of physical abuse is referred to as shaken-baby syndrome, or abusive head trauma, which describes a group of medical symptoms such as brain swelling and retinal hemorrhage resulting from forcefully shaking or causing impact to an infant’s head. A baby’s cry is the number one trigger for shaking. Parents may find themselves unable to soothe a baby’s concerns and may take their frustration out on the child by shaking him or her violently. Other stress factors such as a poor economy, unemployment, and general dissatisfaction with parental life may contribute this type of abuse. While there is no official central registry of shaken-baby syndrome statistics, it is estimated that each year 1,400 babies die or suffer serious injury from being shaken (Barr, 2007).

In a study conducted by the Medill Justice Project using nearly 3,000 cases nationwide, 72.5 percent of those accused of shaken-baby syndrome crimes are men, while 27.5 percent are women [5]. The gender discrepancy found in this study has been attributed to socialization and teaching men how to care for infants. Other studies have questioned whether males are more likely to be the perpetrators or are just more easily convicted given their size and strength.

Corporal Punishment

Physical abuse in children may come in the form of beating, kicking, throwing, choking, hitting with objects, burning, or other methods. Injury inflicted by such behavior is considered abuse even if the parent or caregiver did not intend to harm the child. Other types of physical contact that are characterized as discipline (spanking, for example) are not considered abuse as long as no injury results (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2008).

This issue is rather controversial among modern-day people in the United States. While some parents feel that physical discipline, or corporal punishment, is an effective way to respond to bad behavior, others feel that it is a form of abuse. According to a poll conducted by ABC News, 65 percent of respondents approve of spanking and 50 percent said that they sometimes spank their child.

Tendency toward physical punishment may be affected by culture and education. Those who live in the South are more likely than those who live in other regions to spank their child. Those who do not have a college education are also more likely to spank their child (Crandall, 2011). Currently, 19 states officially allow spanking in the school system; however, many parents may object and school officials must follow a set of clear guidelines when administering this type of punishment.[6] Studies have shown that spanking is not an effective form of punishment and may lead to aggression by the victim, particularly in those who are spanked at a young age (Berlin, 2009).

Although definitions of child abuse vary, international studies conducted by the World Health Organization have shown that a quarter of all adults report having been physically abused as children and 1 in 5 women and 1 in 13 men report having been sexually abused as a child. Additionally, many children are subject to emotional abuse (sometimes referred to as psychological abuse) and to neglect.

In armed conflict and refugee settings, girls are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence, exploitation and abuse by combatants, security forces, members of their communities, aid workers and others.

Watch the UNICEF clip below about the story of a child soldier in South Sudan.

Child abuse occurs at all socioeconomic and education levels and crosses ethnic and cultural lines. Just as child abuse is often associated with stresses felt by parents, including financial stress, parents who demonstrate resilience to these stresses are less likely to abuse (Samuels, 2011). As a parents age increases, the risk of abuse decreases. Children born to mothers who are fifteen years old or younger are twice as likely to be abused or neglected by age five than are children born to mothers ages twenty to twenty-one (George and Lee, 1997).

Drug and alcohol use is also a known contributor to child abuse. Children raised by substance abusers have a risk of physical abuse three times greater than other kids, and neglect is four times as prevalent in these families (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2011). Other risk factors include social isolation, depression, low parental education, and a history of being mistreated as a child. Approximately 30 percent of abused children later abuse their own children (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2006).

Link to Learning

The Child Welfare Information Gateway from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services provides tools, resources, and publications related to child welfare: https://www.childwelfare.gov/.

glossary

- intimate partner violence (IPV):

- violence that occurs between individuals who maintain a romantic or sexual relationship

- "Divorce Rates in the U.S.: Geographic Variation," 2015. Bowling Green State University, https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/anderson-divorce-rate-us-geo-2015-fp-16-21.html. ↵

- Livingston, Gretchen. "Growing Number of Adults Have Remarried." Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2014/11/14/four-in-ten-couples-are-saying-i-do-again/. ↵

- McKenna, Laura (February 2012). Explaining Annette Lareau, or, Why Parenting Style Ensures Inequality. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2012/02/explaining-annette-lareau-or-why-parenting-style-ensures-inequality/253156/ ↵

- "Child Maltreatment 2017," U.S. Department of Child and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm2017.pdf#page=20. ↵

- "Study: Men More Likely to be Accused of Shaking Infants," Northwestern University. https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2013/08/the-medill-justice-projects-study-shows-men-far-more-likely-than-women-to-be-accused-of-violently-shaking-infants/. ↵

- Gershoff, E. T., & Font, S. A. (2016). Corporal Punishment in U.S. Public Schools: Prevalence, Disparities in Use, and Status in State and Federal Policy. Social policy report, 30, 1. ↵