Learning outcomes

- Describe types of economic systems and their historical development

- Use primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary sectors of an economy to compare types of economies

- Compare and contrast capitalism and socialism both in theory and in practice

- Discuss how functionalists, conflict theorists, and symbolic interactionists view the economy and work

The Agricultural Revolution led to development of the first economies that were based on trading goods. Mechanization of the manufacturing process led to the Industrial Revolution and gave rise to two major competing economic systems: capitalism and socialism. Under capitalism, private owners invest their capital and that of others to produce goods and services they can sell in an open market. Prices and wages are set by supply and demand and competition. Under socialism, the means of production is commonly owned, and part or all of the economy is centrally controlled by government. There is no nation that is completely capitalist or socialist; many countries’ economies feature a mix of both systems.

Figure 1. Companies pay to advertise their goods and services in Times Square in New York City, NY. Advertisements are an important facet of the U.S. capitalist economic system. (Photo courtesy of Chris Tagupa/unsplash)

The Development of Economic Systems

Economy is one of human society’s earliest social structures. In sociology, economy refers to the social institution through which a society’s resources are exchanged and managed. The earliest economies were based on trade, which was often a simple exchange in which people traded one item for another. Our earliest forms of writing (such as Sumerian clay tablets) were developed to record transactions, payments, and debts between merchants. As societies grow and change, so do their economies—the economy of a small farming community is very different from the economy of a large nation with advanced technology.

While today’s economic activities are more complex than those early trades, the underlying goals remain the same: exchanging goods and services allows individuals to meet their needs and wants. In 1893, Émile Durkheim noted the change in the way society was held together and was interested in how the division of labor in modern society impacted social solidarity (Ritzer, 2008) [1] Durkheim described what he called “mechanical” and “organic” solidarity that correlates to a society’s economy. Mechanical solidarity exists in simpler societies where social cohesion comes from sharing similar work, education, and religion. Organic solidarity arises out of the mutual interdependence created by the specialization of work. The complex U.S. economy, and the economies of other industrialized nations, meet the definition of organic solidarity. Most individuals perform a specialized task to earn money they use to trade for goods and services provided by others who perform different specialized tasks. In a simplified example, an elementary school teacher relies on farmers for food, doctors for healthcare, carpenters to build shelter, and so on. The farmers, doctors, and carpenters all rely on the teacher to educate their children. They are all dependent on each other and their work.

The dominant economic systems of the modern era are capitalism and socialism, and there have been many variations of each system across the globe. Countries have switched systems as their rulers and economic fortunes have changed. For example, Russia has been transitioning to a market-based economy since the fall of communism in that region of the world. Vietnam, where the economy was devastated by the Vietnam War, restructured to a state-run economy in response, and more recently has been moving toward a socialist-style market economy. In the past, other economic systems reflected the societies that formed them. Many of these earlier systems lasted centuries. These changes in economies raise many questions for sociologists. What are these older economic systems? How did they develop? Why did they fade away? What are the similarities and differences between older economic systems and modern ones?

Economics of Agricultural, Industrial, and Postindustrial Societies

Figure 2. In an agricultural economy, crops and seeds are the most important commodity. Commodities are raw materials or basic goods that are often used as inputs to create other products. They are easily interchangeable, or fungible, meaning that there is little to no difference with other commodities of the same time—for example, wheat grown in Texas is essentially the same as wheat grown in Idaho. Or a barrel of oil from Saudi Arabia is the same as a barrel of oil from the Gulf of Mexico. In a postindustrial society, information is the most valuable resource. (Photo (a) courtesy of Edward S. Curtis/Wikimedia Commons. Photo (b) courtesy of Kārlis Dambrāns/flickr)

Our earliest ancestors lived as hunter-gatherers. Small groups of extended families roamed from place to place looking for subsistence. They would settle in an area for a brief time when there were abundant resources. They hunted animals for their meat and gathered wild fruits, vegetables, and cereals. They ate what they caught or gathered more or less immediately, as they had no way of preserving or transporting it. Once the resources of an area ran low, the group had to move on, and everything they owned had to travel with them. Food reserves only consisted of what they could carry. Many sociologists contend that hunter-gatherers did not have a true economy, because groups did not typically trade with other groups due to the scarcity of goods.

The Agricultural Revolution

The first true economies arrived when people started raising crops and domesticating animals, both of which required staying in one place for a period of time. Although there is still a great deal of disagreement among archaeologists as to the exact timeline, research indicates that agriculture began independently and at different times in several places around the world. The earliest agriculture was in the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East around 11,000–10,000 years ago. Next were the valleys of the Indus, Yangtze, and Yellow rivers in India and China, between 10,000 and 9,000 years ago. The people living in the highlands of New Guinea developed agriculture between 9,000 and 6,000 years ago, while people were farming in Sub-Saharan Africa between 5,000 and 4,000 years ago. Agriculture developed later in the western hemisphere, arising in what would become the eastern United States, central Mexico, and northern South America between 5,000 and 3,000 years ago (Diamond, 2003).

Figure 3. Agricultural practices have emerged in different societies at different times. (Information courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Agriculture began with the simplest of technologies—for example, a pointed stick to break up the soil—but advanced dramatically when people harnessed animals to pull an even more efficient tool for the same task: a plow. With this new technology, one family could grow enough crops not only to feed themselves but also to feed others. Knowing there would be abundant food each year as long as crops were tended, led people to abandon the nomadic life of hunter-gatherers and settle down to farm.

The improved efficiency in food production meant that not everyone had to toil all day in the fields. As agriculture grew, new jobs emerged, along with new technologies. Excess crops needed to be stored, processed, protected, and transported. Farming equipment and irrigation systems needed to be built and maintained. Wild animals needed to be domesticated and herds shepherded. Economies begin to develop because people now had goods and services to trade. At the same time, farmers eventually came to labor for the propertied ruling class.

As more people specialized in non-farming jobs, villages grew into towns and then into cities. Urban areas created the need for administrators and public servants. Disputes over ownership, payments, debts, compensation for damages, and the like led to the need for laws and courts—and the judges, clerks, lawyers, and police who administered and enforced those laws.

At first, most goods and services were traded between small social groups by exchanging one form of goods or services for another known as bartering (Mauss, 1922). This system only works when one person happens to have something the other person needs at the same time. To solve this problem, people developed the idea of a means of exchange that could be used at any time: that is, money. Money refers to an object that a society agrees to assign a value to so it can be exchanged for payment. In early economies, money was often objects like cowry shells, rice, barley, or even rum. Precious metals quickly became the preferred means of exchange in many cultures because of their durability and portability. The first coins were minted in Lydia in what is now Turkey around 650–600 B.C.E. (Goldsborough, 2010). Early legal codes established the value of money and the rates of exchange for various commodities. They also established the rules for inheritance, fines as penalties for crimes, and how property was to be divided and taxed (Horne, 1915). A symbolic interactionist would note that bartering and money are systems of symbolic exchange that require the negotiation of value. Monetary objects took on a symbolic meaning, one that carries into our modern-day use of cash, checks, and debit cards.

The Woman Who Lives without Money

Imagine having no money. If you wanted some french fries, needed a new pair of shoes, or were due to get an oil change for your car, how would you get those goods and services?

This isn’t just a theoretical question. Think about it. What do those on the outskirts of society do in these situations? Think of someone escaping domestic abuse who gave up everything and has no resources. Or an immigrant who wants to build a new life but who had to leave another life behind to find that opportunity. Or a homeless person who simply wants a meal to eat.

This last example, homelessness, is what caused Heidemarie Schwermer to give up money. She was a divorced high school teacher in Germany, and her life took a turn when she relocated her children to a rural town with a significant homeless population. She began to question what serves as currency in a society and decided to try something new.

Schwermer founded a business called Gib und Nimm—in English, “give and take.” It operated on a moneyless basis and strove to facilitate people swapping goods and services for other goods and services—no cash allowed (Schwermer, 2007). What began as a short experiment has become a new way of life. Schwermer says the change has helped her focus on people’s inner value instead of their outward wealth. She wrote two books that tell her story (she’s donated all proceeds to charity) and, most importantly, a richness in her life she was unable to attain with money.

How might our three sociological perspectives view her actions? What would most interest them about her unconventional ways? Would a functionalist consider her aberration of norms a social dysfunction that upsets the normal balance? How would a conflict theorist place her in the social hierarchy? What might a symbolic interactionist make of her choice not to use money—such an important symbol in the modern world?

What do you make of Gib und Nimm?

As city-states grew into countries and countries grew into empires, their economies grew as well. When large empires broke up, their economies broke up too. The governments of newly formed nations sought to protect and increase their markets. They financed voyages of discovery to find new markets and resources all over the world, which ushered in a rapid progression of economic development.

Colonies were established to secure these markets, and wars were financed to take over territory. These ventures were funded in part by raising capital from investors who were paid back from the goods obtained. Governments and private citizens also set up large trading companies that financed their enterprises around the world by selling stocks and bonds.

Governments tried to protect their share of the markets by developing a system called mercantilism. Mercantilism is an economic policy based on accumulating silver and gold by controlling colonial and foreign markets through taxes and other charges. The resulting restrictive practices and exacting demands included monopolies, bans on certain goods, high tariffs, and exclusivity requirements. Mercantilistic governments also promoted manufacturing and, with the ability to fund technological improvements, they helped create the equipment that led to the Industrial Revolution.

The Industrial Revolution

Until the end of the eighteenth century, most manufacturing was done by manual labor. This changed as inventors devised machines to manufacture goods. A small number of innovations led to a large number of changes in the British economy. In the textile industries, the spinning of cotton, worsted yarn, and flax could be done more quickly and less expensively using new machines with names like the Spinning Jenny and the Spinning Mule (Bond 2003). Another important innovation was made in the production of iron: coke from coal could now be used in all stages of smelting rather than charcoal from wood, which dramatically lowered the cost of iron production while increasing availability (Bond, 2003). James Watt ushered in what many scholars recognize as the greatest change, revolutionizing transportation and thereby the entire production of goods with his improved steam engine.

As people moved to cities to fill factory jobs, factory production also changed. Workers did their jobs in assembly lines and were trained to complete only one or two steps in the manufacturing process. These advances meant that more finished goods could be manufactured with more efficiency and speed than ever before.

The Industrial Revolution also changed agricultural practices. Until that time, many people practiced subsistence farming in which they produced only enough to feed themselves and pay their taxes. New technology introduced gasoline-powered farm tools such as tractors, seed drills, threshers, and combine harvesters. Farmers were encouraged to plant large fields of a single crop to maximize profits. With improved transportation and the invention of refrigeration, produce could be shipped safely all over the world.

The Industrial Revolution modernized the world. With growing resources came growing societies and economies. Between 1800 and 2000, the world’s population grew sixfold, while per capita income saw a tenfold jump (Maddison, 2003). While many people’s lives were improving, the Industrial Revolution also birthed many societal problems. There were inequalities in the system. Owners amassed vast fortunes while laborers, including young children, toiled for long hours in unsafe conditions. Workers’ rights, wage protection, and safe work environments are issues that arose during this period and remain concerns today.

Watch this video for a summary of the agriculture and industrial revolution and see how these changes connect with economic growth.

Postindustrial Societies and the Information Age

Postindustrial societies, also known as information societies, have evolved in modernized nations. One of the most valuable goods of the modern era is information. Those who have the means to produce, store, and disseminate information are leaders in this type of society. One way scholars understand the development of different types of societies (like agricultural, industrial, and postindustrial) is by examining their economies in terms of four sectors: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary. Each has a different focus. The primary sector extracts and produces raw materials (like metals and crops). The secondary sector turns those raw materials into finished goods. The tertiary sector provides services: child care, healthcare, and money management. Finally, the quaternary sector produces ideas; these include the research that leads to new technologies, the management of information, and a society’s highest levels of education and the arts (Kenessey, 1987).

In underdeveloped countries, the majority of the people work in the primary sector. As economies develop, more and more people are employed in the secondary sector. In well-developed economies, such as those in the United States, Japan, and Western Europe, the majority of the workforce is employed in service industries. In the United States, for example, almost 80 percent of the workforce is employed in the tertiary sector (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011).

The rapid increase in computer use in all aspects of daily life is a main reason for the transition to an information economy. Fewer people are needed to work in factories because computerized robots now handle many of the tasks. Other manufacturing jobs have been outsourced to less-developed countries as a result of the developing global economy. The growth of the Internet has created industries that exist almost entirely online. Within industries, technology continues to change how goods are produced. For instance, the music and film industries used to produce physical products like CDs and DVDs for distribution. Now those goods are increasingly produced digitally and streamed or downloaded at a much lower physical manufacturing cost. Information and the means to use it creatively have become commodities in a postindustrial economy.

Capitalism and Socialism

Figure 4. Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was one of the founders of Russian communism. J.P. Morgan was one of the most influential capitalists in history. They have very different views on how economies should be run. (Photos (a) and (b) courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Mechanization of the manufacturing process led to the Industrial Revolution which gave rise to two major competing economic systems: capitalism and socialism. Under capitalism, private owners invest their capital and that of others to produce goods and services they can sell in an open market. Prices and wages are set by supply and demand and competition. Under socialism, the means of production is commonly owned, and part or all of the economy is centrally controlled by government. Several countries’ economies feature a mix of both systems.

Watch this video to review the sectors of the economy and then to learn more about economic revolution and the main distinctions between capitalism and socialism.

Capitalism

Figure 5. The New York Stock Exchange is where shares of stock in companies that are registered for public trading are traded (Photo courtesy of Ryan Lawler/Wikimedia Commons)

Scholars don’t always agree on a single definition of capitalism. For our purposes, we will define capitalism as an economic system in which there is private ownership (as opposed to state ownership) and where there is an impetus to produce profit, and thereby wealth. This is the type of economy in place in the United States today. Under capitalism, people invest capital (money or property invested in a business venture) in a business to produce a product or service that can be sold in a market to consumers. The investors in the company are generally entitled to a share of any profit made on sales after the costs of production and distribution are taken out. These investors often reinvest their profits to improve and expand the business or acquire new ones. To illustrate how this works, consider this example. Sarah, Antonio, and Chris each invest $250,000 into a start-up company that offers an innovative baby product. When the company nets $1 million in profits its first year, a portion of that profit goes back to Sarah, Antonio, and Chris as a return on their investment. Sarah reinvests with the same company to fund the development of a second product line, Antonio uses his return to help another start-up in the technology sector, and Chris buys a yacht.

To provide their product or service, owners hire workers to whom they pay wages. The cost of raw materials, the retail price they charge consumers, and the amount they pay in wages are determined through the law of supply and demand and by competition. When demand exceeds supply, prices tend to rise. When supply exceeds demand, prices tend to fall. When multiple businesses market similar products and services to the same buyers, there is competition. Competition can be good for consumers because it can lead to lower prices and higher quality as businesses try to get consumers to buy from them rather than from their competitors.

Wages tend to be set in a similar way. People who have talents, skills, education, or training that is in short supply and is needed by businesses tend to earn more than people without comparable skills. Competition in the workforce helps determine how much people will be paid. In times when many people are unemployed and jobs are scarce, people are often willing to accept less than they would when their services are in high demand. In this scenario, businesses are able to maintain or increase profits by not increasing workers’ wages.

Capitalism in Practice

As capitalists began to dominate the economies of many countries during the Industrial Revolution, the rapid growth of businesses and their tremendous profitability gave some owners the capital they needed to create enormous corporations that could monopolize an entire industry. Many companies controlled all aspects of the production cycle for their industry, from the raw materials, to the production, to the stores in which they were sold. These companies were able to use their wealth to buy out or stifle any competition.

In the United States, the predatory tactics used by these large monopolies caused the government to take action. Starting in the late 1800s, the government passed a series of laws that broke up monopolies and regulated how key industries—such as transportation, steel production, and oil and gas exploration and refining—could conduct business. The main statutes were the Sherman Act of 1890, the Clayton Act of 1914, and the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914. These Acts, first, restricted the formation of cartels and prohibit other collusive practices regarded as being in restraint of trade. Second, they restricted the mergers and acquisitions of organizations that could substantially lessen competition. Third, they prohibited the creation of a monopoly and the abuse of monopoly power.

The United States is considered a capitalist country. However, the U.S. government has a great deal of influence on private companies through the laws it passes and the regulations enforced by government agencies. Through taxes, regulations on wages, guidelines to protect worker safety and the environment, plus financial rules for banks and investment firms, the government exerts a certain amount of control over how all companies do business. State and federal governments also own, operate, or control large parts of certain industries, such as the post office, schools, hospitals, highways and railroads, and many water, sewer, and power utilities. Debate over the extent to which the government should be involved in the economy remains an issue of contention today. Some criticize such involvements as socialism (a type of state-run economy), while others believe intervention and oversight is necessary to protect the rights of workers and the well-being of the general population.

Figure 6. This chart shows how Amazon has developed monopoly-like power in retail when compared with other major corporations like Walmart, Target and JCPenny. How do you think monopolies are in direct contradiction to the idea of competition in capitalist societies? Source: Visual Capitalist, https://www.visualcapitalist.com/extraordinary-size-amazon-one-chart/.

Further Research

One alternative to traditional capitalism is to have the workers own the company for which they work. To learn more about company-owned businesses check out The National Center for Employee Ownership.

Socialism

Figure 7. The economies of China and Russia after World War II were both based on a communist system. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Socialism is an economic system in which there is government ownership (often referred to as “state run”) of goods and their production, with an impetus to share work and wealth equally among the members of a society. Under socialism, everything that people produce, including services, is considered a social product. Everyone who contributes to the production of a good or to providing a service is entitled to a share in any benefits that come from its sale or use. To make sure all members of society get their fair share, governments must be able to control property, production, and distribution.

The focus in socialism is on benefiting society, whereas capitalism seeks to benefit the individual. Socialists claim that a capitalistic economy leads to inequality, with unfair distribution of wealth and individuals who use their power at the expense of society. Socialism strives, ideally, to control the economy to avoid the problems inherent in capitalism.

Within socialism, there are diverging views on the extent to which the economy should be controlled. One extreme believes all but the most personal items are public property. Other socialists believe only essential services such as healthcare, education, and utilities (electrical power, telecommunications, and sewage) need direct control. Under this form of socialism, farms, small shops, and businesses can be privately owned but are subject to government regulation.

The other area on which socialists disagree is on what level society should exert its control. In communist countries like the former Soviet Union, or modern-day China, Vietnam, and North Korea, the national government controls both politics and the economy, and many goods are owned in common. Ideally, these goods would be available to all as needed, although this often plays out differently in theory than in practice. Communist governments generally have the power to tell businesses what to produce, how much to produce, and what to charge for it. There are varying practices within and between communist nations; for example, while China is still considered to be a communist nation, it has adopted many aspects of a market economy. Other socialists believe control should be decentralized so it can be exerted by those most affected by the industries being controlled. An example of this would be a town collectively owning and managing the businesses on which its residents depend.

Because of challenges in their economies, several of these communist countries have moved from central planning to letting market forces help determine many production and pricing decisions. Market socialism describes a sub-type of socialism that adopts certain traits of capitalism, like allowing limited private ownership or consulting market demands. This could involve situations like profits generated by a company going directly to the employees of the company or being used as public funds (Gregory and Stuart, 2003). Many Eastern European and some South American countries have mixed economies. Key industries are nationalized and directly controlled by the government; however, most businesses are privately owned but regulated by the government.

LInk to Learning

Watch this Crash Course video on capitalism and socialism to learn more about the historical context and modern applications of these two political and economic systems.

Organized socialism never became powerful in the United States. The success of labor unions and the government in securing workers’ rights, joined with the high standard of living enjoyed by most of the workforce, made socialism less appealing than the controlled capitalism practiced here.

Figure 8. This map shows countries that have self-proclaimed to be a socialist state at some point. Most of these followed Marxist-Leninist socialism and were also considered communist. The colors indicate the duration that socialism prevailed. (Map courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Socialism in Practice

As with capitalism, the basic ideas behind socialism go far back in history. Plato, in ancient Greece, suggested a republic in which people shared their material goods. Early Christian communities believed in common ownership, as did the systems of monasteries set up by various religious orders. Many of the leaders of the French Revolution called for the abolition of all private property, not just the estates of the aristocracy they had overthrown. Thomas More’s Utopia, published in 1516, imagined a society with little private property and mandatory labor on a communal farm. A utopia has since come to mean an imagined place or situation in which everything is perfect. Most experimental Utopian communities have had the abolition of private property as a founding principle.

Modern socialism really began as a reaction to the excesses of uncontrolled industrial capitalism in the 1800s and 1900s. The enormous wealth and lavish lifestyles enjoyed by the propertied classes contrasted sharply with the miserable conditions of the workers.

Some of the first great sociological thinkers studied the rise of socialism. Max Weber admired some aspects of socialism, especially its rationalism and its emphasis on social reform, but he worried that letting the government have complete control could result in an “iron cage of future bondage” from which there is no escape (Greisman and Ritzer, 1981). Pierre-Joseph Proudon (1809−1865) was another early socialist who thought socialism could be used to create Utopian communities. In his 1840 book, What Is Property?, he famously stated that “property is theft” (Proudon, 1840). By this he meant that if an owner did not work to produce or earn the property, then the owner was stealing it from those who did. Proudon believed economies could work using a principle called mutualism, under which individuals and cooperative groups would exchange products with one another on the basis of mutually satisfactory contracts (Proudon, 1840).

By far the most important influential thinker on socialism is Karl Marx. Through his own writings and those with his collaborator, industrialist Friedrich Engels, Marx used a scientific analytical process to show that throughout history, the resolution of class struggles caused economic and cultural changes. He saw the relationships evolving from slave and owner, to serf and lord, to journeyman and master, to worker and owner. Neither Marx nor Engels thought socialism could be used to set up small Utopian communities. Rather, they believed a socialist society would be created after workers rebelled against capitalistic owners and seized the means of production. They felt industrial capitalism was a necessary step that raised the level of production in society to a point where it could then be reconfigured so as to produce a more egalitarian socialist and then communist state (Marx and Engels, 1848). Marxist ideas have provided much of the foundation for the influential sociological paradigm called conflict theory.

Politics and Socialism: A Few Definitions

In the 2008 presidential election, the Republican Party latched onto what is often considered a dirty word to describe then-Senator Barack Obama’s politics: socialist. (Watch this clip from the History channel, How did ‘Socialism’ Become a Dirty Word, to learn more about the history of the word “socialism.”) It may have been because the president was campaigning by telling workers it’s good for everybody to “spread the wealth around.” But whatever the reason, the label became a weapon of choice for Republicans during and after the campaign. In 2012, Republican presidential aspirant Rick Perry continued this pitch. A New York Times article quotes him as telling a group of Republicans in Texas that President Obama is “hell bent on taking America towards a socialist country” (Wheaton, 2011). Meanwhile, during the first few years of his presidency, Obama worked to create universal healthcare coverage and pushed forth a partial bailout of the nation’s failing automotive industry. President Obama is not the first president to be called a socialist. Franklin D. Roosevelt, 32nd president of the U.S., was attacked as being a socialist when he proposed his New Deal, which included Social Security and unemployment insurance, both of which Americans still enjoy today [2].

In 2016, Bernie Sanders ran for president on the Democratic party platform as a self-described democratic socialist. Two prominent democratic socialists were elected to Congress during the 2018 midterm elections: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, from New York’s 14th congressional district, and Rashida Tlaib, representing Michigan’s 13th congressional district. They are all part of a broader movement within the Democratic party to address inequality in the United States with the goal of instituting some socialist policies alongside existing democratic features.

In Donald Trump’s 2019 State of the Union address, he said, “Here, in the United States, we are alarmed by new calls to adopt socialism in our country. … Tonight, we renew our resolve that America will never be a socialist country,”[3]

Are Rick Perry and Donald Trump correct? Is America headed towards socialism?

Socialism can be interpreted in different ways; however it generally refers to an economic or political theory that advocates for shared or governmental ownership and administration of production and distribution of goods. Often held up in counterpoint to capitalism, which encourages private ownership and production, socialism is not typically an all-or-nothing plan. For example, both the United Kingdom and France, as well as other European countries, have socialized medicine, meaning that medical services are run nationally to reach as many people as possible. These nations are, of course, still essentially capitalist countries with free-market economies.

It seems as though the complicated past of the word socialism, especially as that term has been confused with the repressive totalitarian communism of the Cold War period (1945-1991), has many people worried that any sort of socialist policy, such as universal healthcare, is also an attack on personal freedom. Watch this clip from a Washington Post opinion piece, This is Not Your Grandfather’s Concept of Socialism that explains how socialism today is not the same as in previous generations. Do you think the term means the same thing that it used to?

Convergence Theory

We have seen how the economies of some capitalist countries such as the United States have features that are very similar to socialism. Some industries, particularly utilities, are either owned by the government or controlled through regulations. Public programs such as welfare, Medicare, and Social Security exist to provide public funds for private needs. We have also seen how several large communist (or formerly communist) countries such as Russia, China, and Vietnam have moved from state-controlled socialism with central planning to market socialism, which allows market forces to dictate prices and wages and for some business to be privately owned. In many formerly communist countries, these changes have led to economic growth compared to the stagnation they experienced under communism (Fidrmuc, 2002).

In studying the economies of developing countries to see if they go through the same stages as previously developed nations did, sociologists have observed a pattern they call convergence. This describes the theory that societies move toward similarity over time as their economies develop.

Convergence theory explains that as a country’s economy grows, its societal organization changes to become more like that of an industrialized society. Rather than staying in one job for a lifetime, people begin to move from job to job as conditions improve and opportunities arise. This means the workforce needs continual training and retraining. Workers move from rural areas to cities as they become centers of economic activity, and the government takes a larger role in providing expanded public services (Kerr et al., 1960).

Supporters of the theory point to Germany, France, and Japan—countries that rapidly rebuilt their economies after World War II. They point out how, in the 1960s and 1970s, East Asian countries like Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan converged with countries with developed economies. They are now considered developed countries themselves.

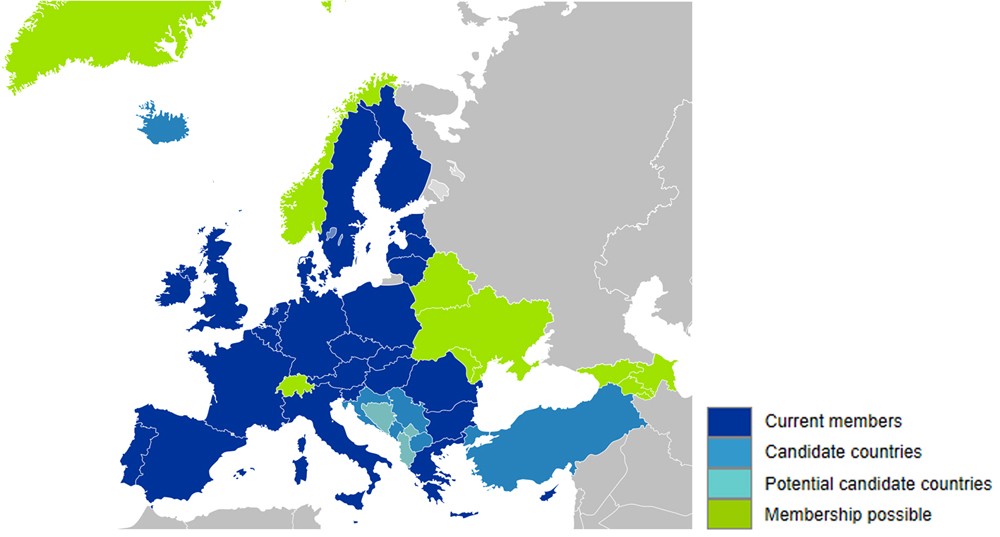

Figure 9. Sociologists look for signs of convergence and divergence in the societies of countries that have joined the European Union. (Map courtesy of the European Union)

To experience this rapid growth, the economies of developing countries must to be able to attract inexpensive capital to invest in new businesses and to improve traditionally low productivity. They also need access to new, international markets for buying and selling goods. If these characteristics are not in place, then their economies cannot catch up. This is why the economies of some countries are diverging rather than converging (Abramovitz, 1986).

Another key characteristic of economic growth regards the implementation of technology. A developing country can bypass some steps of implementing technology that other nations faced earlier. Television and telephone systems are a good example. While developed countries spent significant time and money establishing elaborate system infrastructures based on metal wires or fiber-optic cables, developing countries today can go directly to cell phone and satellite transmission with much less investment.

Another factor affects convergence concerning social structure. Early in their development, countries such as Brazil and Cuba had economies based on cash crops (coffee or sugarcane, for instance) grown on large plantations by unskilled workers. The elite ran the plantations and the government, with little interest in training and educating the populace for other endeavors. This restricted economic growth until the power of the wealthy plantation owners was challenged (Sokoloff and Engerman, 2000). Improved economies generally lead to wider social improvement. Society benefits from improved educational systems, and more broadly shared prosperity will ideally allow people more time for learning and leisure.

- George Ritzer (2008). Sociological Theory. McGraw Hill. New York ↵

- Roosevelt Institute (2012). Franklin D. Roosevelt: Socialist or “Champion of Freedom”? Retrieved from http://rooseveltinstitute.org/rediscovering-governmentfranklin-d-roosevelt-socialist-or-champion-freedom/. ↵

- Pramuk, Jacob (2019). Expect Trump to make more ‘socialism’ jabs as he faces tough 2020 re-election fight. CNBC. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2019/02/06/trump-warns-of-socialism-in-state-of-the-union-as-2020-election-starts.html. ↵