Learning outcomes

- Explain functionalist views on deviance

- Explain how conflict theorists understand deviance

- Describe and differentiate between symbolic interactionists’ approach to deviance

- Differentiate between functionalist, conflict theorist, and symbolic interactionist explanations for deviance and crime

Since the early days of sociology, scholars have developed theories that attempt to explain what deviance and crime mean to society. These theories can be grouped according to the three major sociological paradigms: functionalism, symbolic interactionism, and conflict theory. Let’s revisit marijuana legalization from a theoretical perspective. How can sociological theories help explain the trends and corresponding human behavior and group patterns we discussed in the first section?

Conflict theorists would focus their attention on power and inequality. Who has the power to criminalize, decriminalize, and legalize marijuana use? How has the criminalization of marijuana disproportionately affected minorities and the poor?

Functionalist theorists might examine how the legalization of marijuana might benefit state economies and also how this issue has served to increase social solidarity and redefine social norms.

Interactionist theorists would likely focus on the perceptions of marijuana use and the symbolic nature of the marijuana leaf over time. Labeling is also of interest to interactionists–who gets labeled (the by whom is examined by conflict theorists).

Functionalism and Deviance

Figure 1. Functionalists believe that deviance plays an important role in society and can be used to challenge people’s views. Protesters, such as these PETA members, often use this method to draw attention to their cause. (Photo courtesy of David Shankbone/flickr)

Functionalism

Sociologists who follow the functionalist approach are concerned with the way the different elements of a society contribute to the whole. They view deviance as a key component of a functioning society. Social disorganization theory, strain theory, and social control theory represent the main functionalist perspectives on deviance in society.

Émile Durkheim: The Essential Nature of Deviance

Émile Durkheim believed that deviance is a necessary part of a successful society and that it serves three functions: 1) it clarifies norms and increases conformity, 2) it strengthens social bonds among the people reacting to the deviant, and 3) it can help lead to positive social change and challenges to people’s present views (1893).

For instance, segregation laws remained intact for nearly a century in the United States after slavery was abolished. Those who violated these norms reinforced their legitimacy for those in power, which often led to even harsher laws and sanctions, which in turn led to increased conformity or adherence to the norms. Norm violators were often severely punished, even lynched, which led to increased social bonds among racist whites. On the other hand, when norm violations became more widespread and collective, as a result of various historical and cultural factors (i.e. war in Vietnam, other social movements, televised police brutality, etc.), this cycle of continued deviance eventually led to social and legal change. A key example of this dynamic is the Civil Rights Movement, which corrected many historical wrongs by continuously challenging the dominant society’s values and norms.

Social Disorganization Theory

Developed by researchers at the University of Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s, social disorganization theory asserts that crime is most likely to occur in communities with weak social ties and the absence of social control. Several sociologists at the time, who viewed the city as a laboratory for study, were dubbed “The Chicago School.” These sociologists included Robert Park and Ernest Burgess (1916 and 1925) became the first to utilize an ecological approach, which examined society much as an ecologist examines an organisms and their environment—by paying attention to the social, institutional, and cultural contexts of people-environment relations. They studied deviance by examining rapid changes to the neighborhoods, caused by population increases, immigration, and urbanization in Chicago. Park, a journalist and sociologist, suggested a program to increase the number of playgrounds to counteract social disorganization and juvenile delinquency.

Proponents of social disorganization theory believe that individuals who grow up in impoverished areas are more likely to participate in deviant or criminal behaviors than an individual from a wealthy neighborhood with a good school system and families who are involved positively in the community. Social disorganization theory points to broad social factors as the cause of deviance. A person isn’t born a criminal but becomes one over time, often based on factors in his or her social environment.

Figure 2. Camden, New Jersey. (Photo courtesy of Apollo 1758/Wikimedia Commons)

Although this theory sounds like common sense, critics argue that it places blame on the neighborhoods themselves, which opens the door for politicians to point out social issues like drug use, disrupted families, and violence as endemic to low income neighborhoods, thus allowing them to circumvent the larger structural issues that give rise to these predicaments.

Let’s examine Camden, New Jersey, once one of America’s deadliest cities. As a city of 74,000, there were 58 homicide victims in 1995, and 67 in 2012 (a rate of about 87 murders per 100,000 residents), which ranked Camden fifth nationwide. In 2017, there were 22 homicides [1].

In 2013, the Camden Police Department was disbanded, reimagined, and renamed the Camden County Police Department, with fewer officers, lower pay—and a strategic shift toward “community policing” (Holder, 2018). The police chief, who has been on the Camden force for over 25 years, says “Nothing stops a bullet like a job” and stresses the importance of increasing access to social services, economic opportunities, and good public schools. In his emphasis on multiple causal factors, he sounds like a functionalist!

By strengthening essential social institutions in communities (a macro approach) and working to increase citizen-police relations, that is, how police see themselves and how residents view police (a micro intervention), Camden provides us an example of how sociological theories can help explain deviance but also inform social policy.

Strain Theory/Anomie Theory of Deviance

In 1938 Robert Merton expanded on Durkheim’s idea that deviance is an inherent part of a functioning society by developing strain theory (also called the anomie theory of deviance), which notes that access to the means of achieving socially acceptable goals plays a part in determining whether a person conforms and accepts these goals or rebels and rejects them. For example, from birth we’re encouraged to achieve the American Dream of financial success. A woman who attends business school, receives her MBA, and goes on to make a million-dollar income as CEO of a company is said to be a success. However, not everyone in our society stands on equal footing. A person may have the socially acceptable goal of financial success but lack a socially acceptable way to reach that goal. Much more common might be the young person who wants financial security and success but attends a failing school and is not able to attend college, does not have connections in business or finance, and might not have any CEOs in their immediate circle. The young person might be attracted to other types of entrepreneurial activities outside of the corporate world that are more accessible, such as selling stolen goods and/or drugs, gambling, and/or other types of street-level commerce. Another path might be to embezzle from his employer. These types of crimes will be discussed later, but this is one example of the contrast between “crime in the streets” and “crime in the suites.”

Merton defined five ways people respond to this gap between having a socially accepted goal and having no socially accepted way to pursue it.

- Conformity: Those who conform choose not to deviate. Conformists pursue their goals to the extent that they can through socially accepted means. This is the most common option.

- Innovation: Innovators pursue goals they cannot reach through legitimate means by instead using criminal or deviant means.

- Ritualism: People who ritualize lower their goals until they can reach them through socially acceptable ways. These members of society focus on conformity rather than pursuing an unrealistic dream.

- Retreatism: Others retreat and reject society’s goals and means. For example, some beggars and street people have withdrawn from society’s normative goal of financial success.

- Rebellion: A handful of people rebel and replace a society’s goals and means with their own. Terrorists or freedom fighters look to overthrow a society’s goals through socially unacceptable means.

In Table 1, you can see how conformists accept societal goals and means, while innovators, ritualists, retreatists, and rebels reject either societal goals or societal means, or both.

| Table 1. Strain Theory. |

|||

| Societal Goals | Societal Means | Examples | |

| Conformists | Accept | Accept | college students, professionals who strive to do their best and excel at their job |

| Innovators | Reject | Reject | drug dealers, embezzlers, gamblers |

| Ritualists | Reject | Accept | workers who “punch the clock” |

| Retreatists | Reject | Accept | homeless, drug addicted |

| Rebels | Reject/ Replace | Reject/ Replace | radicals, revolutionaries, terrorists |

Watch this video to learn about how structural functionalists think about deviance:

Deviant Subcultures

During the 1950s, a group of sociologists theorized deviance as subcultural. As you recall from an earlier module about culture, a subculture is a group that operates within larger society but is distinctive in the values and norms that govern membership (formal or informal). A subculture usually exhibits some type of resistance to the existing social structure and/or social norms. Oftentimes a subcultural group is visibly, aesthetically distinctive (i.e. goths, emo, skaters, etc.).

Much of this early research was a response to a growing concern about street gangs in Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s, with notorious gangsters like Al Capone in national headlines. In 1927, Frederick Thrasher’s The Gang: A Study of 1,313 Gangs in Chicago highlighted the geography of gang activity within Chicago and examined the “Poverty Belt” as an area within which gang membership would be particularly enticing. Deviant subcultures theorists also utilized The Chicago School’s models and methods to study delinquency.

Albert K. Cohen (1955) stated that “the crucial condition for the emergence of new cultural forms is the existence, in effective interaction with one another, of a number of actors with similar problems of adjustment” (no emphasis added, pp. 12 and 59). Cohen (1955) observed that a “sympathetic moral climate” within which actors’ perception of norms and shared norms is a result of the subculture’s benefit from those norms, which are a “repudiation of the middle class standards.” Walter Miller (1958) broadened Cohen’s framework by looking beyond the “delinquent boys” and using “over eight thousand pages of direct and observational data” in a “slum” district of Chicago. He lists the following six “focal concerns of lower-class culture”: trouble, toughness, smartness, excitement, fate, and autonomy.

This scholarship from the 1950s reflected a growing unrest in post-World War 2 America as the Cold War gained momentum, demonstrating both a fear of ideological dissent from within and a new concern with low income immigrant communities. The work was also implied a gendered exclusionary focus, negating the agency of females as potential deviant actors.

Marvin Wolfgang and Franco Ferracuti published The Subculture of Violence in 1967, which blended criminology, psychology, and sociology in an attempt to theorize the causes of assault behavior and homicide. They used empirical data which showed violence as being localized among specific groups and said it “reflects differences in learning about violence as a problem-solving mechanism” (1967, p. 159). Wolfgang and Ferracuti suggest the value systems in subcultural groups, particularly inner city men, differ from central value systems and result in more violence (1967, 97).

Social Control Theory

Another functionalist theory of deviance is Travis Hirschi’s (1969) social control theory. Similar to Comte’s original question, “What holds society together?” Hirschi asked, “Why do people adhere to social norms?” In other words, why aren’t people more deviant? Building from Durkheim’s work on social solidarity, Hirschi looked at bonds to conventional social institutions as reasons people feel connected to society and thereby less likely to be deviant. He identified four types of bonds: attachment, commitment, involvement, and belief.

Let’s apply these types of bonds to an example. Say a high school student is trying to decide whether to skip a class to go to the mall with friends. He or she might consider the following:

- Attachment: how their teacher and school administration would think about them if they skipped school and/or how their parent/s’ opinion would be affected (“If my parents find out they will be very disappointed”).

- Commitment: how much they value their education and what they would miss (“I like my American history class and would miss the unit on school desegregation”).

- Involvement: how much time has been invested in school up until this point (“Why spoil a “clean record” by skipping one class?”).

- Belief: how the school’s attendance policy reflects societal beliefs about the importance of education (“I want to go to college and know that attending class will be important to my success and future job prospects”).

We can also imagine more serious forms of deviance and consider how attachment, commitment, involvement, and belief might operate in other scenarios. In what ways can this theory help inform prevention strategies, especially for young people? How can we strengthen attachment and commitment, for example?

Conflict Theory and Deviance

Conflict theory looks to social and economic factors as the causes of crime and deviance. Unlike functionalists, conflict theorists don’t see these factors as positive functions of society. They see them as evidence of inequality in the system. They also challenge social disorganization theory and control theory and argue that both ignore racial and socioeconomic issues and oversimplify social trends (Akers, 1991). Conflict theorists also look for answers to the correlation of gender and race with wealth and crime.

Karl Marx: An Unequal System

Conflict theory was greatly influenced by the work of 19th-century German philosopher, economist, and social scientist Karl Marx. Marx believed that the general population was divided into two groups. He labeled the wealthy, who controlled the means of production and business, the bourgeoisie. He labeled the workers who depended on the bourgeoisie for employment and survival the proletariat. Marx believed that the bourgeoisie centralized their power and influence through government, laws, and other authority agencies in order to maintain and expand their positions of power in society. Thus, Marx viewed the laws as instruments of oppression for the proletariat that are written and enforced to maintain the economic status quo and to protect the interests of the ruling class. Though Marx spoke little of deviance, he wrote a great deal about laws and developed a legal theory that created the foundation for conflict theorists.

C. Wright Mills: The Power Elite

In his book The Power Elite (1956), sociologist C. Wright Mills described the existence of what he dubbed the power elite, a small group of wealthy and influential people at the top of society who disproportionately control power and resources. Wealthy executives, politicians, celebrities, and military leaders often have access to national and international power, and in some cases, their decisions affect everyone in society. Because of this, the rules of society are stacked in favor of a privileged few who then manipulate them to maintain their positions. It is these people who decide what is criminal and what is not, and the effects are often felt most by those who have little power. Mills’ theories explain why celebrities such as Chris Brown and Paris Hilton, or once-powerful politicians such as Eliot Spitzer and Tom DeLay, can commit crimes and suffer little or no legal retribution.

Crime, Social Class, and Race

While crime is often associated with the underprivileged, crimes committed by the wealthy and powerful remain an under-punished and costly problem within society. The American Sociological Association’s 1939 President Edwin Sutherland coined the term “white-collar crime” in his address “White Collar Criminality,” which was one of the few such addresses to make front-page news.[2] He defined the term as “crime committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of his occupation.” Typically, these are “nonviolent crimes committed in commercial situations for financial gain” and according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), white-collar crime is estimated to cost the United States more than $300 billion annually. [3] When former advisor and financier Bernie Madoff was arrested in 2008, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission reported that the estimated losses of his financial Ponzi scheme fraud were close to $50 billion (SEC, 2009). In contrast, property crimes, which include burglary, larceny-theft, motor vehicle theft, and arson, in 2015 resulted in losses estimated at $14.3 billion (FBI, 2015).

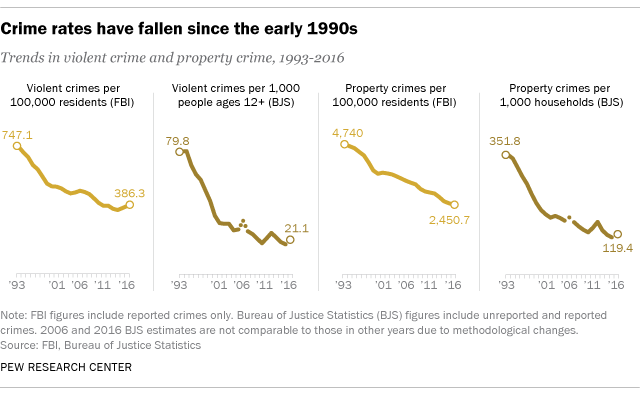

Conflict theorists also quickly point out that “crime in the suites” is often committed by white men, whereas “crime in the streets” disproportionately affects communities of color as both perpetrators and victims of property crimes. Property crimes have fallen dramatically over the past twenty years (see chart below); it is also important to keep in mind that only 36 percent of property crimes are reported to police[4] .

Figure 3. Although public perception tends to contradict this data, crime rates have fallen since the early 1990s. “5 facts about crime in the U.S..” Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. (January 30, 2018). “Crime Rates Have Fallen since the Early 1990s.” Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. (February 15, 2017).

Crack, Cocaine, and Opioids

In the 1980s, there was a “crack epidemic” that swept the country’s poorest urban communities. Its pricier counterpart, cocaine, was often the drug of choice for wealthy whites. Most studies show rates of drug use among whites and blacks were similar. From a pharmaceutical standpoint, crack and cocaine are nearly the same in terms of effect.

In 1986, federal law mandated that being caught in possession of 50 grams of crack was punishable by a ten-year prison sentence. An equivalent prison sentence for cocaine possession, however, required possession of 5,000 grams. In other words, the sentencing disparity was 1 to 100 (New York Times Editorial Staff, 2011). This inequality in the severity of punishment for crack versus cocaine paralleled the class and race of the respective users.

A conflict theorist would note that those in society who hold the power make the laws concerning crime that benefit their own interests, while the powerless classes who lack the resources to make such decisions suffer the consequences. Thus, since powder cocaine use was associated with wealthy whites, the laws were enacted to be lenient on powder cocaine but extremely punitive toward crack-cocaine. The crack-cocaine punishment disparity remained until 2010, when President Obama signed the Fair Sentencing Act, which decreased the disparity to 1 to 18 (The Sentencing Project, 2010).

Today, we are in the midst of an “opioid epidemic.” Unlike the 1980s crack epidemic, the opioid epidemic is considered a public health crisis and has widespread support for prevention and treatment programs. Since disproportionate numbers of drug overdose deaths have been among white Americans, conflict theorists would suggest that those in power are more likely to advocate policy changes to help these drug addicts rather than punish them. Why are whites more likely to overdose? The answer, ironically, might be racism; studies show that doctors are more reluctant to prescribe painkillers to minorities because they mistakenly believe minority patients feel less pain and/or are more likely to misuse or sell the prescribed drugs[5]

Feminist Theory and Deviance

Women who are regarded as criminally deviant are often seen as being doubly deviant. They have broken the laws but they have also violated gender norms governing appropriate female behavior, whereas men’s criminal behavior is seen as consistent with their ostensibly aggressive, self-assertive character. This double standard also explains the tendency to medicalize women’s deviance, to see it as the product of physiological or psychiatric pathology. For example, in the late 19th century, kleptomania was a diagnosis used in legal defenses that linked an extreme desire for department store commodities with various forms of female physiological or psychiatric illness. The fact that “good” middle- and upper-class women, who were at that time coincidentally beginning to experience the benefits of independence from men, would turn to stealing in department stores to obtain the new feminine consumer items on display there, could not be explained without resorting to diagnosing the activity as an illness of the “weaker” sex (Kramar, 2011).

Feminist analysis focuses on the way gender inequality influences the opportunities to commit crime and the definition, detection, and prosecution of crime. In part the gender difference revolves around patriarchal attitudes toward women and the disregard for matters considered to be of a private or domestic nature.

For example, until 1969, abortion was illegal in Canada, meaning that hundreds of women died or were injured each year when they received illegal abortions (McLaren and McLaren, 1997). It was not until the Canadian Supreme Court ruling in 1988 that struck down the law that it was acknowledged that women are capable of making their own choice, in consultation with a doctor, about the procedure. The U.S. Supreme Court in Roe v. Wade (1973) decided in a 7-2 decision that states cannot unduly restrict abortions. Since then, a plethora of restrictions including waiting periods, restrictions on public funding for abortions, mandated counseling, parental involvement for minors, and others have made it exceedingly difficult. The State of Mississippi, for example, has one abortion clinic in the state, whereas California has 152 clinics as of 2014. Read about other differences between the most restrictive state, Mississippi, and the least restrictive state, California.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an African-American woman is almost five times as likely to have an abortion than a white woman, and a Latina more than twice as likely.[6]

Abortion has been declining with approximately 1.1 million abortions performed in 2011, at a rate of 16.9 abortions for every 1,000 women of childbearing age, down from a peak of 29.3 per 1,000 in 1981 (Dutton, 2014). Low-income women in all racial groups are more likely to experience unintended pregnancies, largely due to a lack of health insurance and access to contraception. The most effective and long-term contraception, an intrauterine device or IUD, costs between $500-1000 and office visit fees are in addition to the cost of the IUD itself; community health centers and Medicaid typically do not cover 100% of the costs, but often IUDs are covered by private insurance.

Regulating women’s bodies is nothing new, particularly when it comes to minority women in the U.S. White slave owners raped black female slaves with impunity and then increased their “property” with the offspring. Nearly one-third of women of child-bearing age in Puerto Rico were sterilized between 1930 and 1970, as funded by the U.S. Department of Health, Welfare, and Funding to mitigate high levels of unemployment and poverty. Although this was “voluntary,” women were often pressured to undergo sterilization after giving birth[7]

In addition to examining the ways in which the state regulates women’s bodies, feminist theorists also look at violent crimes against women that are sexual in nature. In the #MeToo era, women from many different groups (i.e. actors, gymnasts, students) have come forward to say that they were sexually harassed and/or sexually assaulted by a boss or supervisor, a team doctor, a university gynecologist, or other co-workers. The broadcast media and social media have been rife with stories of #MeToo, which feminists are examining from a macrosociological approach (power and structures of power) and a microsociological approach (hashtag movement, personal identification with others who have similar experiences).

Sexual Assault in Canada: A Case Study

Until the 1970s, two major types of criminal deviance were largely ignored or were difficult to prosecute as crimes: sexual assault and spousal assault. Through the 1970s, women worked to change the criminal justice system and establish rape crisis centers and battered women’s shelters, bringing attention to domestic violence. In 1983 the Criminal Code was amended to replace the crimes of rape and indecent assault with a three-tier structure of sexual assault (ranging from unwanted sexual touching that violates the integrity of the victim to sexual assault with a weapon or threats or causing bodily harm to aggravated sexual assault that results in wounding, maiming, disfiguring, or endangering the life of the victim) (Kong et al., 2003). Johnson (1996) reported that in the mid-1990s, when violence against women began to be surveyed systematically in Canada, 51 percent of Canadian women had been subject to at least one sexual or physical assault since the age of 16.

The goal of the amendments was to emphasize that sexual assault is an act of violence, not a sexual act. Previously, rape had been defined as an act that involved penetration and was perpetrated against a woman who was not the wife of the accused. This had excluded spousal sexual assault as a crime and had also exposed women to secondary victimization by the criminal justice system when they tried to bring charges. Secondary victimization occurs when the women’s own sexual history and her willingness to consent are questioned in the process of laying charges and reaching a conviction, which as feminists pointed out, increased victims’ reluctance to press charges.

In particular feminists challenged the twin myths of rape that were often the subtext of criminal justice proceedings presided over largely by men (Kramar, 2011). The first myth is that women are untrustworthy and tend to lie about assault out of malice toward men, as a way of getting back at them for personal grievances. The second myth, is that women will say “no” to sexual relations when they really mean “yes.” Typical of these types of issues was the judge’s comment in a Manitoba Court of Appeals case in which a man pleaded guilty to sexually assaulting his twelve- or thirteen-year-old babysitter:

The girl, of course, could not consent in the legal sense, but nonetheless was a willing participant. She was apparently more sophisticated than many her age and was performing many household tasks including babysitting the accused’s children. The accused and his wife were somewhat estranged (cited in Kramar, 2011).

Because the girl was willing to perform household chores in place of the man’s estranged wife, the judge assumed she was also willing to engage in sexual relations. In order to address this type of issue, feminists successfully pressed the Supreme Court to deliver rulings that restricted a defense attorney’s access to a victim’s medical and counseling records, and rules of evidence were changed to prevent a woman’s past sexual history from being used against her. Consent to sexual intercourse was redefined as what a woman actually says or does, not what the man believes to be signaling consent. Feminists also argued that spousal assault was a key component of patriarchal power. Typically it was hidden in the household and largely regarded as a private, domestic matter in which police were reluctant to get involved.

Interestingly, women and men report similar rates of spousal violence—in 2009, 6 percent had experienced spousal violence in the previous five years—but women are more likely to experience more severe forms of violence including multiple victimizations and violence leading to physical injury (Sinha, 2013). In order to empower women, feminists pressed lawmakers to develop zero-tolerance policies that would support aggressive policing and prosecution of offenders. These policies oblige police to pursue charges in cases of domestic violence when a complaint is made, whether or not the victim wishes to press charges (Kramar, 2011).

In 2009, 84 percent of violent spousal incidents reported by women to police resulted in charges being pursued. However, according to victimization surveys only 30 percent of actual incidents were reported to police. The majority of women who did not report incidents to the police stated that they either dealt with them in another way, felt they were a private matter, or did not think the incidents were important enough to report. A significant proportion, however, did not want anyone to find out (44 percent), did not want their spouse to be arrested (40 percent), or were too afraid of their spouse (19 percent) (Sinha, 2013).

Watch this video to examine how conflict theorists think about deviance:

Think It Over

- Pick a famous politician, business leader, or celebrity who has been arrested recently. What crime did he or she allegedly commit? Who was the victim? Explain his or her actions from the point of view of one of the major sociological paradigms. What factors best explain how this person might be punished if convicted of the crime?

- In what ways do race and class intersect when theorizing deviance from a conflict perspective?

Symbolic Interactionism and Deviance

Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism is a theoretical approach that can be used to explain how societies and/or social groups come to view behaviors as deviant or conventional. Labeling theory and differential association theory fall within the realm of symbolic interactionism.

Labeling Theory

Although all of us violate norms from time to time, few people would consider themselves deviant. Those who do, however, have often been labeled “deviant” by society and have gradually come to believe it themselves. Labeling theory examines the ascribing of a deviant behavior to another person by members of society. Thus, what is considered deviant is determined not so much by the behaviors themselves or the people who commit them, but by the reactions of others to these behaviors. As a result, what is considered deviant changes over time and can vary significantly across cultures.

Watch this video for an example of how labeling theory is applied in the case of a cancer patient who is interested in using medical marijuana.

Sociologist Edwin Lemert expanded on the concepts of labeling theory and identified two types of deviance that affect identity formation. Primary deviance is a violation of norms that does not result in any long-term effects on the individual’s self-image or interactions with others. Speeding is a deviant act, but receiving a speeding ticket generally does not make others view you as a bad person, nor does it alter your own self-concept. Individuals who engage in primary deviance still maintain a feeling of belonging in society and are likely to continue to conform to norms in the future.

Sometimes, in more extreme cases, primary deviance can morph into secondary deviance. Secondary deviance occurs when a person’s self-concept and behavior begin to change after his or her actions are labeled as deviant by members of society. The person may begin to take on and fulfill the role of a “deviant” as an act of rebellion against the society that has labeled that individual as such. For example, consider a high school student who often cuts class and gets into fights. The student is reprimanded frequently by teachers and school staff, and soon enough, he develops a reputation as a “troublemaker.” As a result, the student starts acting out even more and breaking more rules; he has adopted the “troublemaker” label and embraced this deviant identity. Secondary deviance can be so strong that it bestows a master status on an individual. A master status is a label that describes the chief characteristic of an individual. Some people see themselves primarily as doctors, artists, or grandfathers. Others see themselves as beggars, convicts, or addicts.

Differential Association Theory

One core premise of culture and socialization is that individuals learn the values and norms of a given culture and that this learning process is lifelong. This is particularly helpful when we think about deviance because differential association theorists apply this core premise to deviance. How many of you have committed a deviant act with someone else? A sibling? A friend? Consider something like underage drinking, which often occurs with peers and/or with older siblings. By the time many students arrive on college campuses (still underage), underage drinking has become normalized so that is seems “everyone” is doing it.

In criminology, differential association is a theory developed by Edwin Sutherland (1883–1950) proposing that through interaction with others, individuals learn the values, attitudes, techniques, and motives for criminal behavior. Differential association theory is the most talked-about of the learning theories of deviance. This theory focuses on how individuals learn to become criminals, but it does not concern itself with why they become criminals.

Differential association predicts that an individual will choose the criminal path when the balance of definitions for law-breaking exceeds those for law-abiding. This tendency will be reinforced if social association provides active people in the person’s life. The earlier in life an individual comes under the influence high status people within a group, the more likely the individual is to follow in their footsteps. This does not deny that there may be practical motives for crime. If a person is hungry but has no money, there is a temptation to steal. But the use of “needs” and “values” is equivocal. To some extent, both non-criminal and criminal individuals are motivated by the need for money and social gain.

Sutherland’s Nine Points

The principles of Sutherland’s theory of differential association can be summarized into nine key points.

- Criminal behavior is learned.

- Criminal behavior is learned in interaction with other persons in a process of communication.

- The principal part of the learning of criminal behavior occurs within intimate personal groups.

- When criminal behavior is learned, the learning includes techniques of committing the crime (which are sometimes very complicated, sometimes simple) and the specific direction of motives, drives, rationalizations, and attitudes.

- The specific direction of motives and drives is learned from definitions of the legal codes as favorable or unfavorable.

- A person becomes delinquent because of an excess of definitions favorable to violation of law over definitions unfavorable to violation of the law.

- Differential associations may vary in frequency, duration, priority, and intensity.

- The process of learning criminal behavior by association with criminal and anti-criminal patterns involves all of the mechanisms that are involved in any other learning.

- While criminal behavior is an expression of general needs and values, it is not explained by those needs and values, since non-criminal behavior is an expression of the same needs and values.

Figure 4. Differential association theory predicts that an individual will choose the criminal path when the balance of definitions for law-breaking exceeds those for law-abiding.

An important quality of differential association theory is the frequency and intensity of interaction. The amount of time that a person is exposed to a particular definition and at what point the interaction began are both crucial for explaining criminal activity. The process of learning criminal behavior is really not any different from the process involved in learning any other type of behavior. Sutherland maintains that there is no unique learning process associated with acquiring non-normative ways of behaving.

One very unique aspect of this theory is that it works to explain more than just juvenile delinquency and crime committed by lower class individuals. Since crime is understood to be learned behavior, the theory is also applicable to white-collar, corporate, and organized crime.

One critique leveled against differential association stems from the idea that people can be independent, rational actors and individually motivated. This notion of one being a criminal based on his or her environment is problematic—the theory does not take into account personality traits that might affect a person’s susceptibility to these environmental influences.

The Right to Vote

Figure 5. Should a former felony conviction permanently strip a U.S. citizen of the right to vote? (Photo courtesy of Joshin Yamada/flickr.

Before she lost her job as an administrative assistant, Leola Strickland postdated and mailed a handful of checks for amounts ranging from $90 to $500. By the time she was able to find a new job, the checks had bounced, and she was convicted of fraud under Mississippi law. Strickland pleaded guilty to a felony charge and repaid her debts; in return, she was spared from serving prison time.

<img class=”wp-image-3902″ src=”https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/courses-images/wp-content/uploads/sites/2034/2016/05/10144941/Screen-Shot-2018-09-10-at-9.49.12-AM.png” alt=” Cartogram showing mishapen states to show the disproportionate number of persons disenfranchised in each state. The Southern States of Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, and Florida are exceptionally large with rates between 2 to 10%. The Northern states such as Washington, Montana, North Dakota, Minnesota, and Wisconsin are shown to have lower rates between Figure 6. Cartogram of Total Disenfranchisement Rates by State, 2016. This Cartogram adjusts the size of the state to represent the number of persons disenfranchised in each state. You can see the the southeastern states have disproportionately high numbers of disenfranchised voters. Image from “6 million lost voters”, https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/6-million-lost-voters-state-level-estimates-felony-disenfranchisement-2016/.

Strickland appeared in court in 2001. More than ten years later, she is still feeling the sting of her sentencing. Why? Because Mississippi is one of twelve states in the United States that bans convicted felons from voting (ProCon, 2011).

To Strickland, who said she had always voted, the news came as a great shock. She isn’t alone. As of 2016, an estimated 6.1 million people are disenfranchised due to a felony conviction which equates to approximately 2.5 percent of the total U.S. voting age population or 1 in every 40 adults [8] These individuals include inmates, parolees, probationers, and even people who have never been jailed, such as Leola Strickland.

While 1 in 40 voting age adults is disenfranchised, when we begin to break it down by racial and ethnic groups the picture becomes much more stark, as 1 in 13 African Americans are disenfranchised. Since felon disenfranchisement is a state-by-state law, African American disenfranchisement rates in Florida, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia now exceed 20 percent of the adult voting age population (Uggen, Larson, & Shannon, 2016).

6 Million Lost Voters: State-Level Estimates of Felony Disenfranchisement, 2016 Christopher Uggen, Ryan Larson, and Sarah Shannon October 2016

Figure 7. African American Felony Disenfranchisement Rates, 2016. African American disenfranchisement numbers are high in many states, but in Florida, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia, over 20% of the African American voting population is disenfranchised. Image from “6 million lost voters”, https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/6-million-lost-voters-state-level-estimates-felony-disenfranchisement-2016/.

With two 21st century elections (2000 and 2016) in which the candidate with the most votes did not win (Al Gore in 2000 and Hillary Clinton in 2016), one of which led to an official recount (2000 Election), there has been increased pressure for states with prohibitive voting measures to examine them. Particularly in the State of Florida, a swing state, in which nearly 1.5 million individuals are currently disenfranchised post-sentence (Uggen, Larson & Shannon, 2016). On January 23, 2018 Floridians for a Fair Democracy garnered 766,200 signatures to get an amendment on the 2018 ballot that would give the ability to vote back to Floridians with felony convictions that have completed their sentences. To see what happened track the results at the Brennan Center for Justice, which includes state by state updates on disenfranchisement.

Think It Over

- Is it fair to deny citizens the right to vote? What factors are important? Should this be a federal issue or a state issue? Using your sociological imagination, what other states’ rights issues have become federal or constitutional issues and why?

Summary of Theoretical Explanations of Deviance

The three major sociological paradigms offer different explanations for the motivation behind deviance and crime. Functionalists point out that deviance is a social necessity since it reinforces norms by reminding people of the consequences of violating them. Violating norms can open society’s eyes to injustice in the system.

Conflict theorists argue that crime stems from a system of inequality that keeps those with power at the top and those without power at the bottom.

Symbolic interactionists focus attention on the socially constructed nature of the labels related to deviance. Crime and deviance are learned from the environment and enforced or discouraged by those around us.

Review each of the main theories associated with each perspective below.

| Functionalism | Associated Theorist | Deviance arises from: |

| Strain Theory | Robert Merton | A lack of ways to reach socially accepted goals by accepted methods |

| Social Disorganization Theory | University of Chicago researchers | Weak social ties and a lack of social control; society has lost the ability to enforce norms with some groups |

| Social Control Theory | Travis Hirschi | Deviance results from a feeling of disconnection from society; social control is directly affected by the strength of social bonds |

| Conflict Theory | Associated Theorist | Deviance arises from: |

| Unequal System | Karl Marx | Inequalities in wealth and power that arise from the economic system |

| Power Elite | C. Wright Mills | Ability of those in power to define deviance in ways that maintain the status quo |

| Symbolic Interactionism | Associated Theorist | Deviance arises from: |

| Labeling Theory | Edwin Lemert | The reactions of others, particularly those in power who are able to determine labels |

| Differential Association Theory | Edwin Sutherlin | Learning and modeling deviant behavior seen in other people close to the individual |

Watch this video to review some of the major theories covered in this module. You’ll examine the symbolic interactionist paradigms of differential association and labeling theory, and also the functionalist paradigm of strain theory.

Think It Over

- Choose a public figure who has effected a major, controversial political and or legal change. To what extant were this person’s actions or beliefs considered deviant when they first emerged? How can the process by which they were eventually accepted and became new norms be explained by applying the major sociological paradigms? What norms needed to be re-examined? Which paradigm seems most useful? Why?

glossary

- conflict theory:

- a theory that examines social and economic factors as the causes of criminal deviance

- deviant subcultures theory:

- several theories that posit poverty and other community conditions give rise to certain subcultures through which adolescents acquire values that promote deviant behavior

- differential association theory:

- a theory that states individuals learn deviant behavior from those close to them who provide models of and opportunities for deviance

- doubly deviant:

- a term used to refer to females who have broken the law and gender norms about appropriate female behavior

- labeling theory:

- the idea that the ascribing of a deviant behavior to another person by members of society affects how a person self-identifies and behaves; related to self-fulfilling prophecy

- master status:

- a label that describes the chief characteristic of an individual

- power elite:

- a small group of wealthy and influential people at the top of society who hold the power and resources

- primary deviance:

- a violation of norms that does not result in any long-term effects on the individual’s self-image or interactions with others

- secondary deviance:

- deviance that occurs when a person’s self-concept and behavior begin to change after his or her actions are labeled as deviant by members of society

- secondary victimization:

- occurs when the women’s own sexual history and her willingness to consent are questioned in the process of laying charges and reaching a conviction

- social control theory:

- a theory that states social control is directly affected by the strength of social bonds and that deviance results from a feeling of disconnection from society

- social disorganization theory:

- a theory that asserts crime occurs in communities with weak social ties and the absence of social control

- strain theory:

- a theory that addresses the relationship between having socially acceptable goals and having socially acceptable means to reach those goals

- twin myths of rape:

- the first myth is that women are untrustworthy and tend to lie about assault out of malice toward men, as a way of getting back at them for personal grievances and the second myth is that women will say “no” to sexual relations when they really mean “yes”

Candela Citations

- Introduction to Theories of Social Deviance. Authored by: Sarah Hoiland and Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by: Sarah Hoiland and Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Family dinner. Authored by: skeeze. Provided by: pixabay. Located at: https://pixabay.com/en/family-eating-at-the-table-dining-619142/. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Introduction and objectives, modified from Introduction to Sociology 2e. Authored by: OpenStax CNX. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d/Introduction_to_Sociology_2e. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@3.49

- Authored by: Get Budding. Provided by: Unsplash. Located at: https://unsplash.com/photos/Bu6BSErSL_M. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved. License Terms: https://unsplash.com/license

- Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance. Authored by: OpenStax CNX. Located at: https://cnx.org/contents/AgQDEnLI@10.1:OY7OWJCz@6/Theoretical-Perspectives-on-Deviance. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@3.49

- William Little. Provided by: BC Open Textbooks. Located at: https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/. Project: Introduction to Sociology. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Criminal Silhouette. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Criminal_Silhouette_L.svg. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Theory & Deviance: Crash Course Sociology #19. Provided by: CrashCourse. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=06IS_X7hWWI&index=20&list=PL8dPuuaLjXtMJ-AfB_7J1538YKWkZAnGA. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Pew Research Data, 5 facts about crime in the U.S.. Authored by: John Gramlich. Provided by: Pew Research Center. Located at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/01/30/5-facts-about-crime-in-the-u-s/. License: All Rights Reserved

- labeling theory video. Authored by: Sociology Live!. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QHSvZZ1pnm0. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- 6 million lost voters images. Authored by: Uggen, C. Larson, R. and S. Shannon. (2016). . Located at: https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/6-million-lost-voters-state-level-estimates-felony-disenfranchisement-2016. Project: The Sentencing Project. License: All Rights Reserved

- Perspectives on Deviance: Differential Association, Labeling Theory, and Strain Theory. Authored by: Jeffrey Walsh. Provided by: Khan Academy. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MSucylf4KhY. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Holder, S. 2018. What happened to crime in Camden? City Lab. ↵

- Edwin H. Sutherland, ASA Presidents, ASA. http://www.asanet.org/edwin-h-sutherland ↵

- "White-collar crime." Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/white-collar_crime. ↵

- Gramlich, J. "Five facts about crime," Pew Research Center.(2018) https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/10/17/facts-about-crime-in-the-u-s/ ↵

- Lopez, G. (2016). Why are black Americans less affected," Vox. https://www.vox.com/2016/1/25/10826560/opioid-epidemic-race-black ↵

- Dutton, Z. (2014). Abortion's racial gap. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/09/abortions-racial-gap/380251/ ↵

- Andrews, K. (2017) The dark history of Latina sterilization. https://www.panoramas.pitt.edu/health-and-society/dark-history-forced-sterilization-latina-women. ↵

- Uggen, C. Larson, R. and S. Shannon. (2016). 6 million lost voters. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/6-million-lost-voters-state-level-estimates-felony-disenfranchisement-2016/ ↵