Development of Photography

Background

The word “photograph” is based on the Greek phos meaning light and graphe meaning drawing, together meaning drawing with light. Essentially, a photograph is created when a light-sensitive surface is exposed to light, leaving a mark on said surface.

There are a number of important precursors to photography. In the 5th century BCE, before the first camera was ever invented, Chinese and Greek philosophers described the “pinhole camera,” a lightproof box with a tiny hole in one side that allowed light to pass through and project an inverted image one side. The camera obscura is a version of the pinhole camera, and was often used as a tool by artists such as Leonardo Da Vinci as a technique to create paintings. The process of photography was effectually engaged in creating a permanent image from the process outlined originally by the camera obscura.

Camera obscura design: This diagram illustrates the components of a camera obscura.

Camera photography was invented in the first decades of the 19th century, and even at this early point, it was able to capture more information, and with greater speed, than painting or sculpture. Nicephore Niepce was a French inventor who is known to have produced the first permanent photoetching in 1822. However, his process took a great deal of time; up to eight hours were needed to expose a single image. Niepce began to work with Louis Daguerre and the two conducted experiments with silver compounds, based on a theory of Johann Heinrich Schultz, who proved that the mixture of silver and chalk darkens when it is exposed to light. Niepce died in 1833 but Daguerre continued on this path and eventually invented the daguerreotype in 1837. The daguerreotype was an incredibly important discovery for photography due to its speed and ease of use. It represents the first commercially successful photographic process. Eventually, France agreed to pay Daguerre for his formula in exchange for announcing his discovery as the gift of France, which he did in 1839.

The Earliest Photography

The earliest photography consisted of monochromatic or black and white shots. Even after color photography was invented, black and white photography still prevailed due to its lower cost and preferable appearance. During the mid-19th century, many scientists and inventors began working on the development of photography. A number of chemical and physical photographic variations were made during the mid-19th century including the invention of the cyanotype, ambrotype, tintype, and negative on albumen.

John Herschel was an important figure to the development of photography. He is credited with creating the first glass negative, and was among the first to use the terms photography, negative, and positive. In addition, he discovered a solution that could be used to “fix” photographs in order to make them more permanent. William Fox Talbot worked to refine Daguerre’s process in order to make the new photographic medium more available to the masses. He also invented the calotype process, which produces a paper print from a negative image. Talbot’s photograph of the Oriel window in Lacock Abbey is the oldest negative in existence.

The 1860s were a defining decade for photography. In addition to the American Civil War (1861–65), the first war in American history to be documented with photographs, the 1860s also brought photography to the middle class. While the first half of the century introduced expensive daguerreotypes, the latter half of the century is defined by the development of cheaper photographic techniques. For example, the ambrotype mimicked the look of the daguerreotype with its reflective surface; however, the newer technology used a light-sensitized glass surface instead of copper, which made for a much cheaper photograph to produce and purchase. Likewise, the tintype eclipsed the ambrotype later in the decade by replacing glass with tin, an even cheaper material, and one that dried much quicker than glass. However, it was the albumen print, paper positives that retained the image quality of metal surfaces, that proved to be the winning technology, lasting well into the 20th century.

Albumen print by Alexander Gardner, 1862: This print by Alexander Gardner depicts bodies of Confederate artillerymen near Dunker church.

Since the earliest photographic developments, many scientists and artists have taken great interest in photography’s inherent abilities. Artists have used photography to study movement and motion, details that before this point could not be seen by the naked eye, as we see in Eadweard Muybridge’s studies from 1887. Photography represents the first instance of an artistic medium being used widely by the masses as a mode of visual expression.

The Horse in Motion, 1886, Eadweard Muybridge: The Horse in Motion by Eadweard Muybridge illustrates the artist’s preoccupation with documenting motion and his use of photography as a sequential art form.

In the arts, the medium was valued for its replication of exact details, and for its reproduction of artworks for publication. But photographers struggled for artistic recognition throughout the century. It was not until in Paris’s Universal Exposition of 1859, twenty years after the invention of the medium, that photography and “art” (painting, engraving, and sculpture) were displayed next to one another for the first time; separate entrances to each exhibition space, however, preserved a physical and symbolic distinction between the two groups. After all, photographs are mechanically reproduced images: Kodak’s marketing strategy (“You press the button, we do the rest,”) points directly to the “effortlessness” of the medium.

Since art was deemed the product of imagination, skill, and craft, how could a photograph (made with an instrument and light-sensitive chemicals instead of brush and paint) ever be considered its equivalent? And if its purpose was to reproduce details precisely, and from nature, how could photographs be acceptable if negatives were “manipulated,” or if photographs were retouched? Because of these questions, amateur photographers formed casual groups and official societies to challenge such conceptions of the medium. They—along with elite art world figures like Alfred Stieglitz—promoted the late nineteenth-century style of “art photography,” and produced low-contrast, warm-toned images like The Terminal that highlighted the medium’s potential for originality.

Alfred Stieglitz, The Terminal, photogravure, 1892

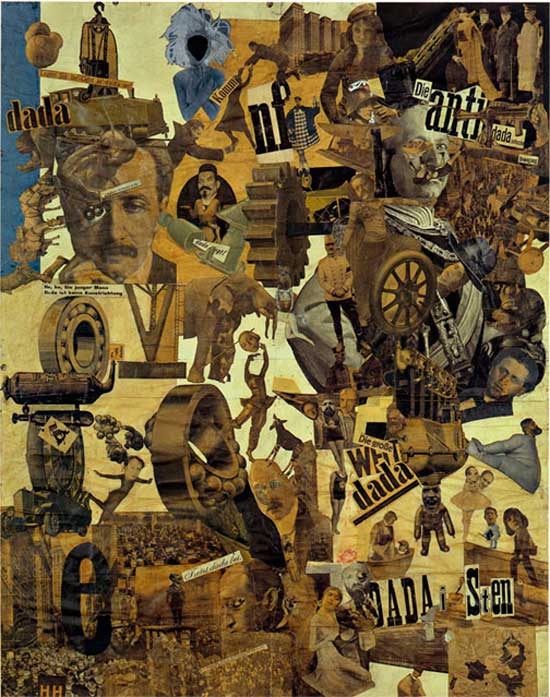

So what transforms the perception of photography in the early twentieth century? Social and cultural change—on a massive, unprecedented scale. Like everyone else, artists were radically affected by industrialization, political revolution, trench warfare, airplanes, talking motion pictures, radios, automobiles, and much more—and they wanted to create art that was as radical and “new” as modern life itself. If we consider the work of the Cubists and Futurists, we often think of their works in terms of simultaneity and speed, destruction and reconstruction. Dadaists, too, challenged the boundaries of traditional art with performances, poetry, installations, and photomontage that use the materials of everyday culture instead of paint, ink, canvas, or bronze.

Picasso, Still Life with Chair Caning, 1912, oil, oilcloth and pasted paper on canvas with rope frame

Giacomo Balla, Hand of the Violinist, 1912 (Hand of the Violinist, 1912, oil on canvas (London, priv. col.)

Hannah Höch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany, 1919-20, photomontage

By the early 1920s, technology becomes a vehicle of progress and change, and instills hope in many after the devastations of World War I. For avant-garde (“ahead of the crowd”) artists, photography becomes incredibly appealing for its associations with technology, the everyday, and science—precisely the reasons it was denigrated a half-century earlier. The camera’s technology of mechanical reproduction made it the fastest, most modern, and arguably, the most relevant form of visual representation in the post-WWI era. Photography, then, seemed to offer more than a new method of image-making—it offered the chance to change paradigms of vision and representation.

With August Sander’s portraits, such as Secretary at a Radio Station, Pastry Cook or Disabled Man, we see an artist attempting to document—systematically—modern types of people, as a means to understand changing notions of class, race, profession, ethnicity, and other constructs of identity. Sander transforms the practice of portraiture with these sensational, arresting images. These figures reveal as much about the German professions as they do about self-image.

August Sander, Disabled Man, 1926

August Sander, Pastry Chef, 1928

August Sander, Secretary at a Radio Station, Cologne, 1931

Cartier-Bresson’s leaping figure in Behind the Gare St. Lazare reflects the potential for photography to capture individual moments in time—to freeze them, hold them, and recreate them. Because of his approach, Cartier-Bresson is often considered a pioneer of photojournalism. This sense of spontaneity, of accuracy, and of the ephemeral corresponded to the racing tempo of modern culture (think of factories, cars, trains, and the rapid pace of people in growing urban centers).

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Behind the Gare St. Lazare, 1932

Umbo (Otto Umbehr), The Roving Reporter, photomontage, 1926

Umbo’s photomontage The Roving Reporter shows how modern technologies transform our perception of the world—and our ability to communicate within it. His camera-eyed, colossal observer (a real-life journalist named Egon Erwin Kisch) demonstrates photography’s ability to alter and enhance the senses. In the early twentieth-century, this medium offered a potentially transformative vision for artists, who sought new ways to see, represent, and understand the rapidly changing world around them.

Film

The first motion picture cameras were invented in Europe during the late nineteenth century. These early “movies” lacked a soundtrack and were normally shown along with a live pianist, organ player or orchestra in the theatre to provide the musical accompaniment. In the United States, film went from being a novelty to an art form with D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation in 1915. In it, Griffith presents a narrative of the Civil War and its aftermath but with a decidedly racist view of American blacks and the Ku Klux Klan.

Flying Gallop Hypothesis Falsified: Galloping horse, animated in 2006 using photos by Eadweard Muybridge.

Film scholars agree it contains many new cinematic innovations and refinements, technical effects and artistic advancements, including a color sequence at the end. It had a formative influence on future films and has had a recognized impact on film history and the development of film as art. In addition, at almost three hours in length, it was the longest film to date (from Filmsite Movie Review: The Birth of a Nation).

Unique to the moving image is its ability to unfold an idea or narrative over time, using the same elements and principles inherent in any artistic medium. Film stills show how dramatic use of lighting, staging and set compositions are embedded throughout an entire film.

Video art, first appearing in the 1960s and 70s, uses magnetic tape to record image and sound together. The advantage of video over film is its instant playback and editing capability. One of the pioneers in using video as an art form was Doris Chase. She began by integrating her sculptures with interactive dancers, using special effects to create dreamlike work, and spoke of her ideas in terms of painting with light. Unlike filmmakers, video artists frequently combine their medium with installation, an art form that uses entire rooms or other specific spaces, to achieve effects beyond mere projection. South Korean video artist Nam June Paik made breakthrough works that comment on culture, technology and politics. Contemporary video artist Bill Viola creates work that is more painterly and physically dramatic, often training the camera on figures within a staged set or spotlighted figures in dark surroundings as they act out emotional gestures and expressions in slow motion. Indeed, his work The Greeting reenacts the emotional embrace seen in the Italian Renaissance painter Jocopo Pontormo’s work The Visitation below.

Jacopo Pontormo, The Visitation, 1528, oil on canvas. The Church of San Francesco e Michele, Carmignano, Italy.

Video art came into existence during the late 1960s and early 1970s as new technology became available outside corporate broadcasting for the production of moving image work. The medium of video being used to create the work, which can then be broadcast, viewed in galleries, distributed as video tapes or DVD discs, or presented as sculptural installations incorporating one or more television sets or video monitors.

History of Video Art

Prior to the introduction of this new technology, moving image production was only available to the consumer through 8 or 16 millimeter film. Many artists found video more appealing than film, particularly when the medium’s greater accessibility was coupled with technologies able to edit or modify the video image. The relative affordability of video also led to its popularity as a medium.

The Art of Video Games Exhibition Crowd, March 16, 2012 – September 30, 2012: Exhibit at the Smithsonian American Art Museum that showcased video games as moving image art works. People walk through a dark gallery of video games that are displayed on the walls.

The first multi-channel video art was Wipe Cycle by Ira Schneider and Frank Gillette. An installation of nine television screens, Wipe Cycle combined live images of gallery visitors, found footage from commercial television, and shots from pre-recorded tapes. The material was alternated from one monitor to the next in an elaborate choreography.

Digital Art

Digital art is a general term for any art that uses digital technology as an essential part of the creative process. Since the 1970s, various names have been used to describe such artwork, including computer art and multimedia art, and digital art itself is placed under the larger umbrella term of new media art.

The impact of digital technology has transformed activities such as painting, drawing, sculpture, and music, while new forms (such as net art, digital installation art, and virtual reality) have become recognized as art. More generally, the term digital artist describes one who creates art using digital technologies. The term digital art is also applied to contemporary art that uses the methods of mass production or digital media.

Digital Production Techniques in Visual Media

Techniques of digital art are used extensively by the mainstream media in advertisements and by filmmakers to produce special effects. Both digital and traditional artists use many sources of electronic information and programs to create their work. Given the parallels between visual art and music, it seems likely that acceptance of the value of digital art parallels the progression to acceptance of electronic music over the last four decades.

Digital art can be purely computer-generated or taken from other sources, such as scanned photographs or images drawn using graphics software. The term may technically be applied to art done using other media or processes and merely scanned into a digital format, but digital art usually describes art that has been significantly modified by a computer program. Digitized text, raw audio, and video recordings are usually not considered digital art alone, but can be part of larger digital art projects. Digital painting is created in a similar fashion to non-digital painting, but it uses software to create and distribute the work.

Jeff Wall, A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai), 1993: The well-known photographer Jeff Wall often uses digital photography to create his works, thereby classifying them as a form of digital art that exemplifies the exceptionally wide-reaching nature of the term itself. Photo shows three figures near a river, bracing themselves against a strong gust of wind. Two thin trees are bending and a stack of papers is flying out of a person’s hands.

Computer-Generated Visual Media

Digital visual art consists of two-dimensional (2D) information displayed on a monitor as well as information mathematically translated into three-dimensional (3D) images and viewed through perspective projection on a monitor. The simplest form is 2D computer graphics, which reflect drawings made using a pencil and paper. In this case, however, the image is on the computer screen and the instrument used to draw might be a stylus or mouse. The creation might appear to be drawn with a pencil, pen, or paintbrush.

Another kind of digital video art is 3D computer graphics, where the screen becomes a window into a virtual environment of arranged objects that are “photographed” by the computer. Many software programs enable collaboration, lending such artwork to sharing and augmentation so users can collaborate on an artistic creation. Computer-generated animations are created with a computer from digital models. The term is usually applied to works created entirely with a computer. Movies make heavy use of computer-generated graphics, which are called computer-generated imagery (CGI) in the film industry.

Computer-generated animation: This example of computer-generated animation, produced using the “motion capture” technique, is another form of digital art. This image shows the different steps to creating a CGI character, from a person being used as a model to the final robot-like character.

Digital installation art constitutes a broad field of activity and incorporates many forms. Some resemble video installations, particularly large-scale works involving projections and live video capture. By using projection techniques that enhance an audience’s impression of sensory development, many digital installations attempt to create immersive environments.

Irrational Geometrics, Pascal Dombis (2008): Irrational Geometrics is a digital art installation. Photo of a man walking through the art installation. Green, swirly lines are projected on the wall behind him.

Candela Citations

- Photography. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-fmcc-hum140/chapter/4-92-photography/?preview_id=456&preview_nonce=98d89339d6&preview=true. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Photography in the Early 20th Century. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/atd-sac-artappreciation/chapter/reading-photography/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Time-Based Media: Film and Video. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/masteryart1/chapter/oer-1-41/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike