Classical Antiquity (or Ancient Greece and Rome) is a period of about 900 years, when ancient Greece and then ancient Rome (first as a Republic and then as an Empire) dominated the Mediterranean area, from about 500 B.C.E. – 400 C.E. We tend to lump ancient Greece and Rome together because the Romans adopted many aspects of Greek culture when they conquered the areas of Europe under Greek control (circa 145 – 30 B.C.E.).

For example, the Romans adopted the Greek pantheon of Gods and Godesses but changed their names—the Greek god of war was Ares, whereas the Roman god of war was Mars. The ancient Romans also copied ancient Greek art. However, the Romans often used marble to create copies of sculptures that the Greeks had originally made in bronze.

Art

Both the Ancient Greeks and the Ancient Romans had enormous respect for human beings, and what they could accomplish with their minds and bodies. They were Humanists (a frame of mind which was re-born in the Renaissance). This was very different from the period following Classical Antiquity—the Middle Ages, when Christianity (with its sense of the body as sinful) came to dominate Western Europe.

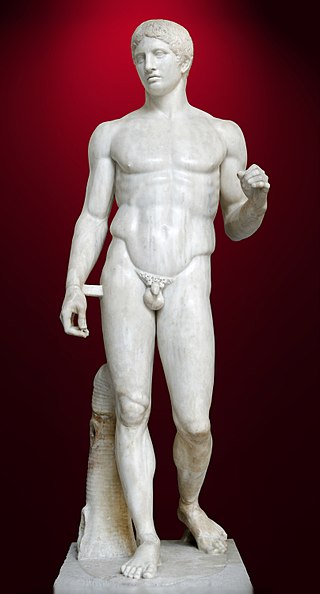

When you imagine Ancient Greek or Roman sculpture, you might think of a figure that is nude, athletic, young, idealized, and with perfect proportions—and this would be true of Ancient Greek art of the Classical period (5th century B.C.E.) as well as much of Ancient Roman art.

Roman Copies of Ancient Greek Art

When we study ancient Greek art, so often we are really looking at ancient Roman art, or at least their copies of ancient Greek sculpture (or paintings and architecture for that matter).

Basically, just about every Roman wanted ancient Greek art. For the Romans, Greek culture symbolized a desirable way of life—of leisure, the arts, luxury and learning.

The Popularity of Ancient Greek Art for the Romans

Greek art became the rage when Roman generals began conquering Greek cities (beginning in 211 B.C.E.), and returned triumphantly to Rome not with the usual booty of gold and silver coins, but with works of art. This work so impressed the Roman elite that studios were set up to meet the growing demand for copies destined for the villas of wealthy Romans. The Doryphoros was one of the most sought after, and most copied Greek sculptures.

A well-preserved Roman period copy of the Doryphoros of Polykleitos in the Naples National Archaeological Museum. Material: marble. Height: 2.12 metres (6 feet 11 inches).

Early Roman art was greatly influenced by the art of Greece and the neighboring Etruscans, who were also greatly influenced by Greek art via trade. As the Roman Republic conquered Greek territory, expanding its imperial domain throughout the Hellenistic world, official and patrician sculpture grew out of the Hellenistic style that many Romans encountered during their campaigns, making it difficult to distinguish truly Roman elements from elements of Greek style. This was especially true since much of what survives of Greek sculpture are actually copies made of Greek originals by Romans. By the 2nd century BCE, most sculptors working within Rome were Greek, many of whom were enslaved following military conquests, and whose names were rarely recorded with the work they created. Vast numbers of Greek statues were also imported to Rome as a result of conquest as well as trade.

Rather than create free-standing works depicting heroic exploits from history or mythology, as the Greeks had, the Romans produced historical works in relief. Small sculptures were considered luxury items and were frequently the object of client-patron relationships. The silver Warren Cup and glass Lycurgus cup are examples of the high quality works that were produced during this period. For a wider section of the population, moulded relief decoration in pottery vessels and small figurines were produced in great quantities, and were often of great quality.

A beardless man has sexual intercourse with a young boy, side B of the so-called Warren Cup.

Lycurgus Cup, no flash

In the 3rd century BCE, Greek art taken during wars became popular, and many Roman homes were decorated with landscapes by Greek artists.

Of the vast body of Roman painting that once existed, only a few examples survive to the modern-age. The most well-known surviving examples of Roman painting are the wall paintings from Pompeii and Herculaneum, that were preserved in the aftermath of the fatal eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE.

Roman fresco with a banquet scene from the Casa dei Casti Amanti, Pompeii

A large number of paintings also survived in the catacombs of Rome, dating from the 3rd century CE to 400, prior to the Christian age, demonstrating a continuation of the domestic decorative tradition for use in humble burial chambers. Wall painting was not considered high art in either Greece or Rome. Sculpture and panel painting, usually consisting of tempera or encaustic painting on wooden panels, were considered more prestigious art forms.

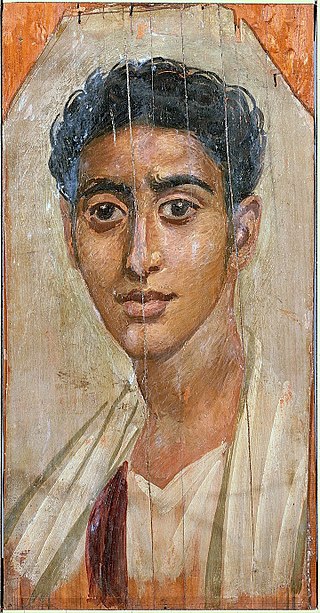

A large number of Fayum mummy portraits, bust portraits on wood added to the outside of mummies by the Romanized middle class, exist in Roman Egypt. Although these are in some ways distinctively local, they are also broadly representative of the Roman style of painted portraits.

A portrait from the late 1st century AD

Roman portraiture during the Republic is identified by its considerable realism, known as veristic portraiture. Verism refers to a hyper-realistic portrayal of the subject’s facial characteristics. The style originated from Hellenistic Greece; however, its use in Republican Rome and survival throughout much of the Republic is due to Roman values, customs, and political life. As with other forms of Roman art, Roman portraiture borrowed certain details from Greek art, but adapted these to their own needs. Veristic images often show their male subject with receding hairlines, deep winkles, and even with warts. While the face of the portrait was often shown with incredible detail and likeness, the body of the subject would be idealized, and did not seem to correspond to the age shown in the face.

Bust of an Old Man. Veristic portraiture of an Old Man. Verism refers to a hyper-realistic portrayal of the subject’s facial characteristics.

Portrait sculpture during the period utilized youthful and classical proportions, evolving later into a mixture of realism and idealism. Advancements were also made in relief sculptures, often depicting Roman victories. The Romans, however, completely lacked a tradition of figurative vase-painting comparable to that of the ancient Greeks, which the Etruscans had also emulated.

The Late Republic

The use of veristic portraiture began to diminish during the Late Republic in the 1st century BCE. During this time, civil wars threatened the empire and individual men began to gain more power. The portraits of Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar, two political rivals who were also the most powerful generals in the Republic, began to change the style of portraits and their use. The portraits of Pompey the Great were neither fully idealized, nor were they created in the same veristic style of Republican senators. Pompey borrowed a specific parting and curl of his hair from Alexander the Great, linking Pompey visually to Alexander’s likeness, and triggering his audience to associate him with Alexander’s characteristics and qualities.

Bust of Pompey the Great. The portraits of Pompey the Great were neither fully idealized, nor were they created in the same veristic style of Republican senators. This bust clearly shows the specific parting and curl of his hair that would have likened him to Alexander the Great.

Literature

Roman literature was, from its very inception, heavily influenced by Greek authors. Some of the earliest works we possess are historical epics telling the early military history of Rome, similar to the Greek epic narratives of Homer, Herodotus, and Thucydides.

Virgil (70 B.C.E.-19 B.C.E.), though generally considered to be an Augustan poet, represents the pinnacle of Roman epic poetry. His Aeneid tells the story of the flight of Aeneas from Troy, and his settlement of the city that would become Rome. The Aeneid is an epic poem in twelve books or chapters [that] tells the story of the Trojan warrior, Aeneas, in the aftermath of the Trojan War. During the sack of Troy, Aeneas fled the city with his father, Anchises, and his son, Ascanius. Led by the prophecies that promised him a future kingdom, he and his followers finally settled in Latium, a region of central Italy. From his descendants were said to come the Roman people.

Depiction of Virgil

The legend of Aeneas’ escape, his journey to Italy, and his role as the ancestor of the Roman people grew out of an episode in Homer’s Iliad that takes place during Achilleus’ rampage on the battlefield. With Apollo’s encouragement, Aeneas (=Aineias, in the Greek spelling) challenges Achilleus. As they fight, Poseidon, the god of the sea, sees that Aeneas is in danger of being slain by Achilleus. He says:

for no reason, for the sake of others’ unhappiness, and always

he gives gifts that please them to the gods who hold the wide heaven.

But come, let us ourselves get him away from death, for fear

the son of Kronos may be angered if now Achilleus

kills this man. It is destined that he shall be the survivor,

that the generation of Dardanos shall not die, without seed

obliterated, since Dardanos was dearest to Kronides

of all his sons that have been born to him from mortal women.

For Kronos’ son has cursed the generation of Priam,

and now the might of Aineias shall be lord over the Trojans,

and his sons’ sons, and those who are born of their seed hereafter. (20.297-308)”

Virgil’s poetry immediately became famous in Rome and was admired by the Romans for two main reasons—first, because he was regarded as their own national poet, spokesman of their ideals and achievements; second, because he seemed to have reached the ultimate of perfection in his art (his structure, diction, metre). For the latter reason, his poems were used as school textbooks, and the 1st-century Roman critic and teacher Quintilian recommended that the educational curriculum should be based on Virgil’s works.

As the Republic expanded, authors began to produce poetry, comedy, history, and tragedy. Lucretius, in his De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things), attempted to explicate science in an epic poem. The genre of satire was also common in Rome, and satires were written by, among others, Juvenal and Persius.

The Age of Cicero

Bust of Cicero. A mid-first century CE bust of Cicero, in the Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Cicero has traditionally been considered the master of Latin prose. The writing he produced from approximately 80 BCE until his death in 43 BCE, exceeds that of any Latin author whose work survives, in terms of quantity and variety of genre and subject matter. It also possesses unsurpassed stylistic excellence. Cicero’s many works can be divided into four groups: letters, rhetorical treatises, philosophical works, and orations. His letters provide detailed information about an important period in Roman history, and offers a vivid picture of public and private life among the Roman governing class. Cicero’s works on oratory are our most valuable Latin sources for ancient theories on education and rhetoric. His philosophical works were the basis of moral philosophy during the Middle Ages, and his speeches inspired many European political leaders, as well as the founders of the United States.

Read this excerpt from On Duty (44 B.C.E.) by Cicero:

Candela Citations

- Art and Literature in the Roman Republic. Authored by: Boundless World History. Provided by: Boundless. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hccc-worldhistory/chapter/art-and-literature-in-the-roman-republic/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- De Officiis. Authored by: M. Tullius Cicero. Provided by: Perseus. Located at: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:2007.01.0048. Project: Perseus Digital Library Project. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- A well-preserved Roman period copy of the Doryphoros of Polykleitos in the Naples National Archaeological Museum. . Authored by: Polykleitos. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doryphoros#/media/File:Doryphoros_MAN_Napoli_Inv6011-2.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Virgil. Authored by: Robert Deryck Williams. Provided by: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.. Located at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Virgil. License: All Rights Reserved

- Warren Cup, side B. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warren_Cup#/media/File:Warren_Cup_BM_GR_1999.4-26.1_n2.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Lycurgus Cup, no flash. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lycurgus_Cup#/media/File:Brit_Mus_13sept10_brooches_etc_046.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Virgil's Aeneid: An Introduction. Authored by: James d'Emilio. Provided by: University of South Florida. Located at: http://shell.cas.usf.edu/~demilio/2211unit3/vrglcint.htm. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Roman fresco with a banquet scene from the Casa dei Casti Amanti, Pompeii. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- A portrait from the late 1st century AD. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fayum_mummy_portraits#/media/File:Egyptian_-_Mummy_Portrait_of_a_Man_-_Walters_323.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright