Early Christian Art

The beginnings of an identifiable Christian art can be traced to the end of the second century and the beginning of the third century. Considering the Old Testament prohibitions against graven images, it is important to consider why Christian art developed in the first place. The use of images will be a continuing issue in the history of Christianity. The best explanation for the emergence of Christian art in the early church is due to the important role images played in Greco-Roman culture.

As Christianity gained converts, these new Christians had been brought up on the value of images in their previous cultural experience and they wanted to continue this in their Christian experience. For example, there was a change in burial practices in the Roman world away from cremation to inhumation. Outside the city walls of Rome, adjacent to major roads, catacombs were dug into the ground to bury the dead. Families would have chambers or cubicula dug to bury their members. Wealthy Romans would also have sarcophagi or marble tombs carved for their burial. The Christian converts wanted the same things. Christian catacombs were dug frequently adjacent to non-Christian ones, and sarcophagi with Christian imagery were apparently popular with the richer Christians.

Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, marble, 359 C.E. (Treasury of Saint Peter’s Basilica)

Junius Bassus, a Roman praefectus urbi or high ranking government administrator, died in 359 C.E. Scholars believe that he converted to Christianity shortly before his death accounting for the inclusion of Christ and scenes from the Bible. (Photograph above shows a plaster cast of the original.)

Themes of Death and Resurrection (Borrowed from the Old Testament)

A striking aspect of the Christian art of the third century is the absence of the imagery that will dominate later Christian art. We do not find in this early period images of the Nativity, Crucifixion, or Resurrection of Christ, for example. This absence of direct images of the life of Christ is best explained by the status of Christianity as a mystery religion. The story of the Crucifixion and Resurrection would be part of the secrets of the cult.

While not directly representing these central Christian images, the theme of death and resurrection was represented through a series of images, many of which were derived from the Old Testament that echoed the themes. For example, the story of Jonah—being swallowed by a great fish and then after spending three days and three nights in the belly of the beast is vomited out on dry ground—was seen by early Christians as an anticipation or prefiguration of the story of Christ’s own death and resurrection. Images of Jonah, along with those of Daniel in the Lion’s Den, the Three Hebrews in the Firey Furnace, Moses Striking the Rock, among others, are widely popular in the Christian art of the third century, both in paintings and on sarcophagi.

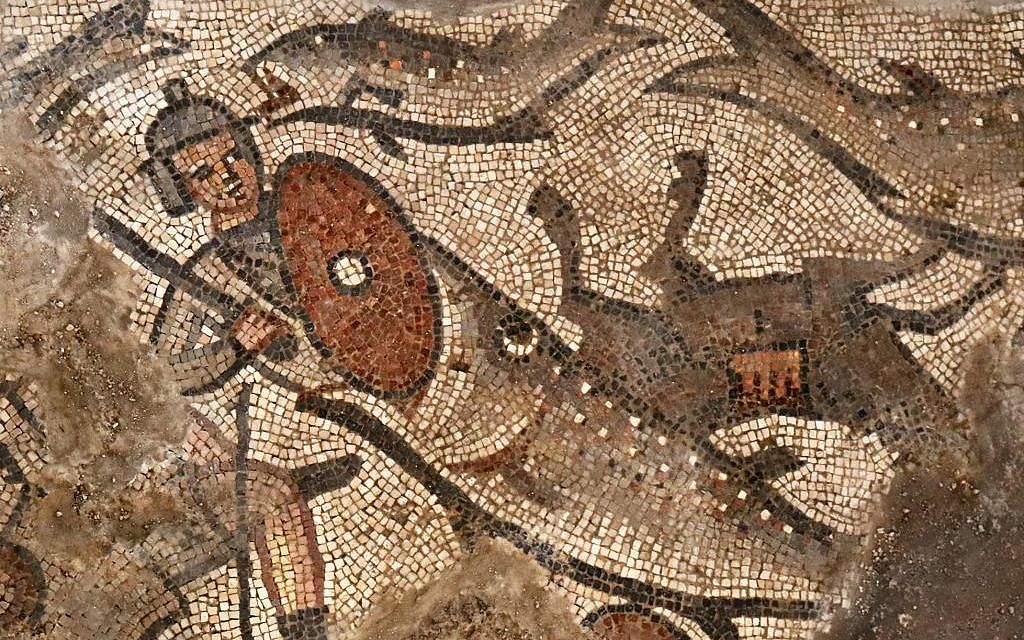

A fish swallows an Egyptian soldier in a mosaic scene depicting the splitting of the Red Sea from the Exodus story, from the 5th-century synagogue at Huqoq, in northern Israel. (Jim Haberman/University of North Carolina Chapel Hill)

All of these can be seen to allegorically allude to the principal narratives of the life of Christ. The common subject of salvation echoes the major emphasis in the mystery religions on personal salvation. The appearance of these subjects frequently adjacent to each other in the catacombs and sarcophagi can be read as a visual litany: save me Lord as you have saved Jonah from the belly of the great fish, save me Lord as you have saved the Hebrews in the desert, save me Lord as you have saved Daniel in the Lion’s den, etc.

One can imagine that early Christians—who were rallying around the nascent religious authority of the Church against the regular threats of persecution by imperial authority—would find great meaning in the story of Moses of striking the rock to provide water for the Israelites fleeing the authority of the Pharaoh on their exodus to the Promised Land.

Early Representations of Christ and the Apostles

Christ, the Catacomb of Domitilla

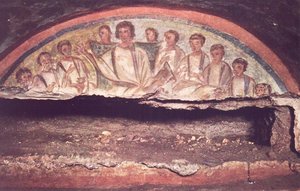

An early representation of Christ found in the Catacomb of Domitilla shows the figure of Christ flanked by a group of his disciples or students. Those experienced with later Christian imagery might mistake this for an image of the Last Supper, but instead this image does not tell any story. It conveys rather the idea that Christ is the true teacher.

Christ draped in classical garb holds a scroll in his left hand while his right hand is outstretched in the so-called ad locutio gesture, or the gesture of the orator. The dress, scroll, and gesture all establish the authority of Christ, who is placed in the center of his disciples. Christ is thus treated like the philosopher surrounded by his students or disciples.

St. Paul |

Sophocles |

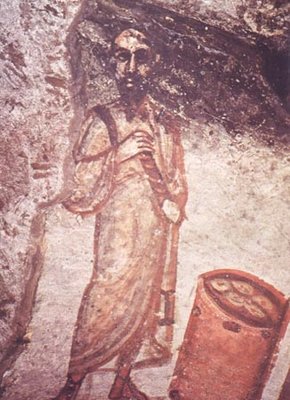

Comparably, an early representation of the apostle Paul, identifiable with his characteristic pointed beard and high forehead, is based on the convention of the philosopher, as exemplified by a Roman copy of a late fourth century B.C.E. portrait of the fifth century B.C.E. playwright Sophocles.

Christianity’s canonical texts and the New Testament

One of the major differences between Christianity and the public cults was the central role faith plays in Christianity and the importance of orthodox beliefs. The history of the early Church is marked by the struggle to establish a canonical set of texts and the establishment of orthodox doctrine.

Questions about the nature of the Trinity and Christ would continue to challenge religious authority. Within the civic cults there were no central texts and there were no orthodox doctrinal positions. The emphasis was on maintaining customary traditions. One accepted the existence of the gods, but there was no emphasis on belief in the gods.

The Christian emphasis on orthodox doctrine has its closest parallels in the Greek and Roman world to the role of philosophy. Schools of philosophy centered around the teachings or doctrines of a particular teacher. The schools of philosophy proposed specific conceptions of reality. Ancient philosophy was influential in the formation of Christian theology. For example, the opening of the Gospel of John: “In the beginning was the word and the word was with God…,” is unmistakably based on the idea of the “logos” going back to the philosophy of Heraclitus (ca. 535 – 475 BCE). Christian apologists like Justin Martyr writing in the second century understood Christ as the Logos or the Word of God who served as an intermediary between God and the World.

Early Medieval Art

An illusion of reality

Classical art, or the art of ancient Greece and Rome, sought to create a convincing illusion for the viewer. Artists sculpting the images of gods and goddesses tried to make their statues appear like an idealized human figure. Some of these sculptures, such as the Aphrodite of Knidos by Praxiteles, were so lifelike that legends spread about the statues coming to life and speaking to people. After all, a statue of a god or goddess in the ancient world was believed to embody deity.

The problem for early Christians

The illusionary quality of classical art posed a significant problem for early Christian theologians. When God dictated the ten commandments to Moses on Mount Sinai, God expressly forbade the Israelites from making any “any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth” (Exodus 20:4). Early Christians saw themselves as the spiritual progeny of the Israelites and tried to comply with this commandment. Nevertheless, many early Christians were converted pagans who were accustomed to images in religious worship. The use of images in religious ritual was visually compelling and difficult to abandon.

Praxiteles, Aphrodite of Cnidos, Roman marble copy after 4th century Greek original (Palazzo Altemps, Rome)

Tertillian asks: Can artists be Christians?

Tertullian, an influential early Christian author living in the second and third centuries, wrote a treatise titled On Idolatry in which he asks if artists could, in fact, be Christians. In this text, he argues that all illusionary art, or all art that seeks to look like something or someone in nature, has the potential to be worshiped as an idol. Arguing fervently against artists as Christians, he acknowledges that there are many artists who are Christians and indeed some who are even priests. In the end, Tertullian asks artists to quit their work and become craftsmen.

St. Augustine: illusionary images are lies

Another influential early Christian writer, St. Augustine of Hippo, was also concerned about images, but for different reasons. In his Soliloquies (386-87), Augustine observes that illusionary images, like actors, are lying. An actor on a stage lies because he is playing a part, trying to convince you that he is a character in the script when in truth he is not. An image lies because it is not the thing it claims to be. A painting of a cat is not a cat, but the artist tries to convince the viewer that it is. Augustine cannot reconcile these lies with patterns of divine truth and therefore does not see a place for images in Christian practice.[1]

Fortunately for art and history, not everyone agreed with Tertullian and Augustine and the use of images persisted. Nevertheless their style and appearance changed in order to be more compatible with theology.

Mosaic in the apse of the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe, 6th century (Ravenna, Italy)

Towards abstraction (and away from illusion)

Christian art, which was initially influenced by the illusionary quality of classical art, started to move away from naturalistic representation and instead pushed toward abstraction. Artists began to abandon classical artistic conventions like shading, modeling and perspective—conventions that make the image appear more real. They no longer observed details in nature to record them in paint, bronze, marble, or mosaic.

Instead, artists favored flat representations of people, animals and objects that only looked nominally like their subjects in real life. Artists were no longer creating the lies that Augustine warned against, as these abstracted images removed at least some of the temptations for idolatry. This new style, adopted over several generations, created a comfortable distance between the new Christian empire and its pagan past.

In Western Europe, this approach to the visual arts dominated until the imperial rule of Charlemagne (800-814) and the accompanying Carolingian Renaissance. This controversy over the legitimacy and orthodoxy of images continued and intensified in the Byzantine Empire. The issue was eventually resolved, in favor of images, during the Second Council of Nicaea in 787.

Carolingian Art

Charlemagne, King of the Franks and later Holy Roman Emperor, instigated a cultural revival known as the Carolingian Renaissance. This revival used Constantine’s Christian empire as its model, which flourished between 306 and 337. Constantine was the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity and left behind an impressive legacy of military strength and artistic patronage.

Charlemagne saw himself as the new Constantine and instigated this revival by writing his Admonitio generalis (789) and Epistola de litteris colendis (c.794-797). In the Admonitio generalis, Charlemagne legislates church reform, which he believes will make his subjects more moral and in the Epistola de litteris colendis, a letter to Abbot Baugulf of Fulda, he outlines his intentions for cultural reform. Most importantly, he invited the greatest scholars from all over Europe to come to court and give advice for his renewal of politics, church, art and literature.

Carolingian art survives in manuscripts, sculpture, architecture and other religious artifacts produced during the period 780-900. These artists worked exclusively for the emperor, members of his court, and the bishops and abbots associated with the court. Geographically, the revival extended through present-day France, Switzerland, Germany and Austria.

Odo of Metz, Palatine Chapel Interior, Aachen, 805

Charlemagne commissioned the architect Odo of Metz to construct a palace and chapel in Aachen, Germany. The chapel was consecrated in 805 and is known as the Palatine Chapel. This space served as the seat of Charlemagne’s power and still houses his throne today.

The Palatine Chapel is octagonal with a dome, recalling the shape of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy (completed in 548), but was built with barrel and groin vaults, which are distinctively late Roman methods of construction. The chapel is perhaps the best surviving example of Carolingian architecture and probably influenced the design of later European palace chapels.

Charlemagne had his own scriptorium, or center for copying and illuminating manuscripts, at Aachen. Under the direction of Alcuin of York, this scriptorium produced a new script known as Carolingian miniscule. Prior to this development, writing styles or scripts in Europe were localized and difficult to read. A book written in one part of Europe could not be easily read in another, even when the scribe and reader were both fluent in Latin. Knowledge of Carolingian miniscule spread from Aachen was universally adopted, allowing for clearer written communication within Charlemagne’s empire. Carolingian miniscule was the most widely used script in Europe for about 400 years.

Figurative art from this period is easy to recognize. Unlike the flat, two-dimensional work of Early Christian and Early Byzantine artists, Carolingian artists sought to restore the third dimension. They used classical drawings as their models and tried to create more convincing illusions of space.

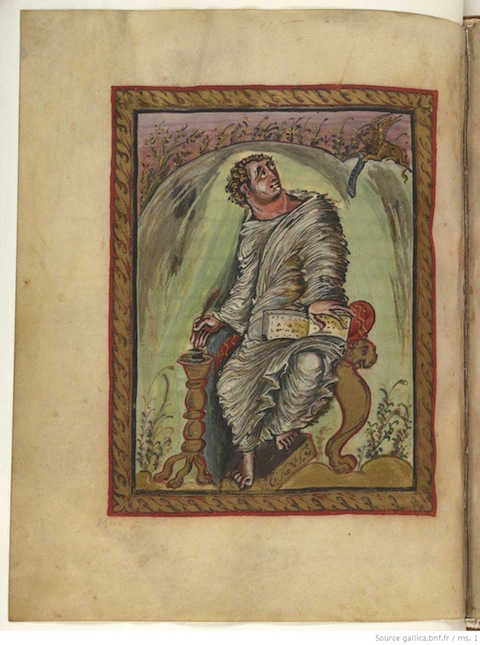

St. Mark from the Godescalc Gospel Lectionary, folio 1v., c. 781-83

This development is evident in tracing author portraits in illuminated manuscripts. The Godescalc Gospel Lectionary, commisioned by Charlemagne and his wife Hildegard, was made circa 781-83 during his reign as King of the Franks and before the beginning of the Carolingian Renaissance. In the portrait of St. Mark, the artist employs typical Early Byzantine artistic conventions. The face is heavily modeled in brown, the drapery folds fall in stylized patterns and there is little or no shading. The seated position of the evangelist would be difficult to reproduce in real life, as there are spatial inconsistencies. The left leg is shown in profile and the other leg is show straight on. This author portrait is typical of its time.

St. Mark from the Ebbo Gospels, folio 18v., c. 816-35

The Ebbo Gospels were made c. 816-35 in the Benedictine Abbey of Hautvillers for Ebbo, Archbishop of Rheims. The author portrait of St. Mark is characteristic of Carolingian art and the Carolingian Renaissance. The artist used distinctive frenzied lines to create the illusion of the evangelist’s body shape and position. The footstool sits at an awkward unrealistic angle, but there are numerous attempts by the artist to show the body as a three-dimensional object in space. The right leg is tucked under the chair and the artist tries to show his viewer, through the use of curved lines and shading, that the leg has form. There is shading and consistency of perspective. The evangelist sitting on the chair strikes a believable pose.

Ottonian Art

Charlemagne, like Constantine before him, left behind an almost mythic legacy. The Carolingian Renaissance marked the last great effort to revive classical culture before the Late Middle Ages. Charlemagne’s empire was led by his successors until the late ninth century. In early tenth century, the Ottonians rose to power and espoused different artistic ideals.

After Charlemagne’s legacy had begun to die out, the warlike tribes in what is now Germany (then Saxony) banded together to elect a king from among their nobility. In 919 C.E., they chose Henry the Liudolfing, the son of a high-ranking duke, a brilliant military strategist and a well-respected leader. Henry, dubbed “the Fowler” because of his hobby of bird hunting, led the Saxon armies to a number of decisive victories against the Magyars and the Danes. These newly secured borders ushered in a period of immense prosperity and artistic productivity for the Saxon empire.

Henry’s son Otto I (who became emperor in 962) lends his name to the “Ottonian” period. He forged an important alliance with the Pope, which allowed him to be crowned the first official Holy Roman Emperor since 924. This contact with Rome was extremely important to Ottonian artistic development, since each Ottonian king was determined to define himself as a Roman Emperor in the style of Constantine and Charlemagne. This meant perpetuating a highly intellectual court and creating an extensive artistic legacy.

Ottonian art takes a number of traditional medieval forms, including elegantly illuminated manuscripts, lavish metalwork, intricate carving, and Romanesque churches and cathedrals. Perhaps the most famous of the Ottonian artistic innovations is the Saxon Romanesque architecture style, which is marked by a careful attention to balance and mathematical harmony. This focus on geometry is based on the texts de Arithmatica and Ars Geometriae by the 6th century philosopher Boethius. The Ottonians held mathematical sciences in high regard and this is reflected in many of their artistic productions.

Church Tower of St Peter Barton on Humber

The illuminated manuscripts produced by Ottonian “scriptoria,” or monastery painting and writing schools, provide documentation of both Ottonian religious and political customs and the stylistic preferences of the period. Manuscripts were most often produced of religious texts, and usually included a dedication portrait commemorating the book’s creation. The royal or religious donor is usually shown presenting the book to the saint of his or her choice.

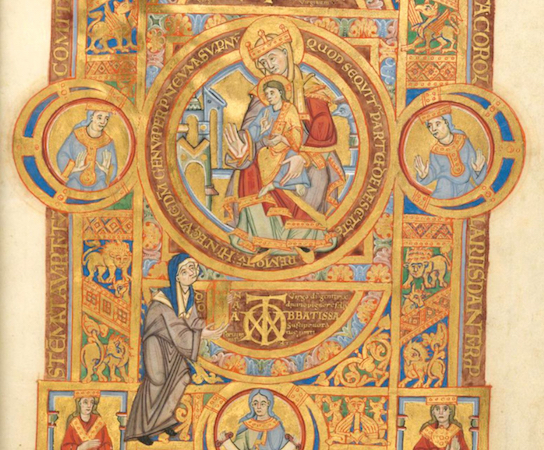

Uta Codex (Uta Presents the Codex to Mary), c. 1020, Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm. 13601, f. 2, recto (digitized)

Here we see a powerful abbess, Uta, presenting her codex to St. Mary. Many manuscripts also included a page depicting the artist or scribe of the work, acknowledging that the production of a book required not only money but also artistic labor.

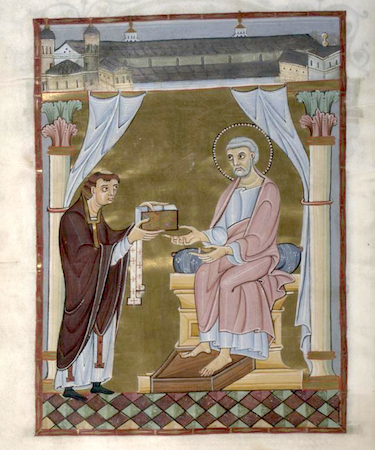

Hillinus Codex (Hillinus Presents the Codex to St. Peter), c.1020, Cologne Dombibliothek, folio 16, verso, manuscript 12 (digitized)

In the Hillinus Codex, a monk presents the codex that he has written or painted (or both!) to St. Peter. The work of the artist and scribe were often one and the same, as can be seen in many of the fantastic decorated initials that begin books or chapters in Ottonian Manuscripts. As you can see from the dedication pictures, the manuscripts in question are often depicted as they were frequently displayed, that is with the text securely enclosed between lavish metal covers.

(Left) Cover, “Dormition of the Virgin,” Gospels of Otto III, c. 998–1001, Munich, Staatsbibliothek, Clm. 4453 ; (right) Doors of the Hildesheim Church, c. 1015

Ottonian metalwork took many forms, but one of the most common productions was bejeweled book covers for their precious manuscripts. This cover on the left is one of the most expensive that survives; it includes not only numerous jewels, but an ivory carving of the death of the Virgin Mary. On a larger scale, clerics like Bernward of Hildesheim, who designed the church we saw earlier, cast his 15′ doors depicting the fall and redemption of mankind out of single pieces of metal (on the right). This was an enormous undertaking, and the process was so complex that it would not be replicated until the Renaissance.

For a modern viewer, Ottonian art can be a little difficult to understand. The depictions of people and places don’t conform to a naturalistic style, and the symbolism is often obscure. When you look at Ottonian art, keep in mind that the aim for these artists was not to create something that looked “realistic,” but rather to convey abstract concepts, many of which are deeply philosophical in nature. The focus on symbolism can also be one of the most fascinating aspects of studying Ottonian art, since you can depend on each part of the compositions to mean something specific. The more time you spend on each composition, the more rewarding discoveries emerge.

Romanesque art

The first international style since antiquity

The term “Romanesque,” meaning in the manner of the Romans, was first coined in the early nineteenth century. Today it is used to refer to the period of European art from the second half of the eleventh century throughout the twelfth (with the exception of the region around Paris where the Gothic style emerged in the mid-12th century). In certain regions, such as central Italy, the Romanesque continued to survive into the thirteenth century. The Romanesque is the first international style in Western Europe since antiquity—extending across the Mediterranean and as far north as Scandinavia. The transmission of ideas was facilitated by increased travel along the pilgrimage routes to shrines such as Santiago de Compostela in Spain (a pilgrimage is a journey to a sacred place) or as a consequence of the crusades which passed through the territories of the Byzantine empire. There are, however, distinctive regional variants—Tuscan Romanesque art (in Italy) for example is very different from that produced in northern Europe.

The relation of art to architecture—especially church architecture—is fundamental in this period. For example, wall-paintings may follow the curvature of the apse of a church as in the apse wall-painting from the church of San Clemente in Taüll (to be discussed), and the most important art form to emerge at this period was architectural sculpture—with sculpture used to decorate churches built of stone.

Sculpture and architecture

Many sculptors may have begun their career as stone masons, and there is a remarkable coherence between architecture and sculpture in churches at this period. The two most important sculptural forms to emerge at this time were the tympanum (the lunette-shaped space above the entrance to a church), and the historiated capital (a capital incorporating a narrative element usually an episode from the Bible or the life of a saint).

One influence on the Romanesque is, as the name implies, ancient Roman art—especially sculpture—which survived in large quantities particularly in southern Europe. This can be seen, for example, in a marble relief representing the calling of St. Peter and St. Andrew from the front frieze of the abbey church of Sant Pere de Rodes on the Catalonian coast. The imprint of the antique can be seen in the deep undercutting in the drapery folds, an effect achieved by the Roman device of the drill, and the individualization of the faces.

Painting and illustration

Classical influence was also frequently mediated through an intermediary—most importantly Byzantine art (especially textiles and painting), but also through earlier medieval styles which had absorbed elements of the classical tradition such as Ottonian art.

The illustrations in the Bury Bible have, for example, been convincingly compared to Byzantine wall-paintings in a church at Asinou in Cyprus which suggests that its artist—a certain Master Hugo (having the name of the artist is unusual during this period) had seen them or a similar source. Monasteries such as that of Bury St. Edmunds in East Anglia in England (where the Bury Bible was made) were important centers of production—especially for the writing and decorating of manuscripts. The Bury Bible is a good example of the remarkable achievements of monastic scriptoria in the Romanesque period.

Pietro Lorenzetti fresco detail, Assisi Basilica, 1310–1329

Monasteries were not the only centers of production. Romanesque art is also associated with towns that were revived and expanded during this period—for the first time since the fall of the Roman empire—a consequence of broad economic expansion (examples include Assisi in Umbria with its Romanesque cathedral–above–or the newly founded town of Puente La Reina in northern Spain on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela).

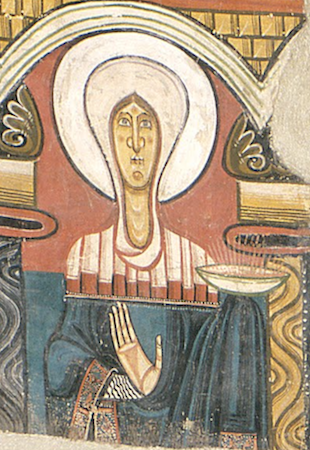

Below him is an equally elongated and distorted figure of the Virgin Mary who holds a chalice with Christ’s blood, a representation of the Holy Grail which predates the earliest written description of the subject. Her presence in the scheme is symptomatic of the growing cult of the Virgin Mary at this period. It would be just as much a mistake to regard the lack of naturalism found in this painting as indicating lack of artistic competence as it would be in a work by Picasso. Rather it indicates that its artist (whose real name we do not know) is not interested in replicating external appearances but rather in conveying a sense of the sacred and communicating the religious teachings of the church. Picasso (who was brought up in Barcelona) greatly admired Catalonian Romanesque, and it is significant that later in his life he kept a poster of this painting in his studio in southern France. We live in a world saturated with images but in the Romanesque period people would rarely encounter them and an image such as this would have made an immense impression.

Metalwork

The distinction between the fine and decorative arts is one that emerges only in the Renaissance and does not apply at this earlier period. If anything the most highly valued works of art during the Romanesque period were objects of metalwork made from precious metals that were frequently produced to house relics (characteristically the body part of a saint, or—in the case of Christ who, the faithful believe ascended to heaven—objects associated with him such as fragments of the so-called true cross on which Christ was thought to have been crucified).

An example of this is the reliquary known as the Stavelot Triptych. It consists of a central panel flanked by side wings that can be closed, a design format derived from Byzantine art but made at the Benedictine monastery of Stavelot in the Mosan region in present day Belgium in the mid-twelfth century. The triptych was commissioned by the abbot, a man called Wibald, whom we know travelled extensively and who acquired, during a trip to Constantinople, the two Byzantine enamel plaques incorporated into the center of the triptych that contain what were believed to be fragments of the true cross.

Secular Romanesque

- There is some irony here since Augustine's position echoes, to some extent, the writing of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato. In book X of The Republic (c. 360 B.C.E.), Plato describes a true thing as having been made by God, while in the earthly sphere, a carpenter, for example, can only build a replica of this truth (Plato uses a bed to illustrate his point). Plato states that a painter who renders the carpenter's bed creates an illusion that is two steps from the truth of God. ↵