Somewhere in La Mancha, in a place whose name I do not care to remember…

This line, arguably the most famous in the history of Spanish literature, is the opening of The Ingenious Nobleman Don Quixote of La Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes, the first modern novel.

Published in two parts in 1605 and 1615, this is the story of Alonso Quijano, a 16th-century Spanish hidalgo, a noble, who is so passionate about reading that he leaves home in search of his own chivalrous adventures. He becomes a knight-errant himself: Don Quixote de la Mancha. By imitating his admired literary heroes, he finds new meaning in his life: aiding damsels in distress, battling giants and righting wrongs… mostly in his own head.

But Don Quixote is much more. It is a book about books, reading, writing, idealism vs. materialism, life … and death. Don Quixote is mad. “His brain’s dried up” due to his reading, and he is unable to separate reality from fiction, a trait that was appreciated at the time as funny. However, Cervantes was also using Don Quixote’s insanity to probe the eternal debate between free will and fate. The misguided hero is actually a man fighting against his own limitations to become who he dreams to be.

Open-minded, well-travelled, and very well-educated, Cervantes was, like Don Quixote himself, an avid reader. He also served the Spanish crown in adventures that he would later include in the novel. After defeating the Ottoman Empire in the battle of Lepanto (and losing the use of his left hand, becoming “the one-handed of Lepanto”), Cervantes was captured and held for ransom in Algiers.

This autobiographical episode and his escape attempts are depicted in “The Captive’s Tale” (in Don Quixote Part I), where the character recalls “a Spanish soldier named something de Saavedra”, referring to Cervantes’s second last name. Years later, back in Spain, he completed Don Quixote in prison, due to irregularities in his accounts while he worked for the government.

Tilting at windmills

In Part I, Quijano with his new name, Don Quixote, gathers other indispensable accessories to any knight-errant: his armour; a horse, Rocinante; and a lady, an unwitting peasant girl he calls Dulcinea of Toboso, in whose name he will perform great deeds of chivalry.

While Don Quixote recovers from a disastrous first campaign as a knight, his close friends, the priest and the barber, decide to examine the books in his library. Their comments about his chivalric books combine literary criticism with a parody of the Inquisition’s practices of burning texts associated with the devil. Although a few volumes are saved (Cervantes’s own La Galatea among them), most books are burned for their responsibility in Don Quixote’s madness.

In Don Quixote’s second expedition, the peasant Sancho Panza joins him as his faithful squire, with the hopes of becoming the governor of his own island one day. The duo diverges in every aspect. Don Quixote is tall and thin, Sancho is short and fat (panza means “pot belly”). Sancho is an illiterate commoner and responds to Don Quixote’s elaborate speeches with popular proverbs. The mismatched couple has remained as a key literary archetype since then.

In perhaps the most famous scene from the novel, Don Quixote sees three windmills as fearful giants that he must combat, which is where the phrase “tilting at windmills” comes from. At the end of Part I, Don Quixote and Sancho are tricked into returning to their village. Sancho has become “quixotized”, now increasingly obsessed with becoming rich by ruling his own island.

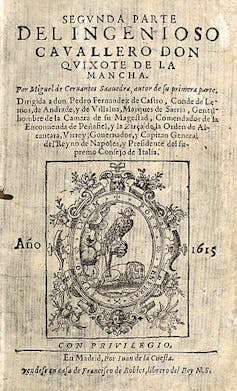

The cover of Don Quixote Part II (1615)

Don Quixote was an enormous success, being translated from Spanish into the main European languages and even reaching North America. In 1614 an unknown author, Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda, published an apocryphal second part. Cervantes incorporated this spurious Don Quixote and its characters into his own Part II, adding yet another chapter to the history of modern narrative.

Whereas Part I was a reaction to chivalric romances, Part II is a reaction to Part I. The book is set only one month after Don Quixote and Sancho’s return from their first literary quest, after they are notified that a book retelling their story has been published (Part I).

The rest of Part II operates as a game of mirrors, recalling and rewriting episodes. New characters, such as aristocrats who have also read Part I, use their knowledge to play tricks on Don Quixote and Sancho for their own amusement. Deceived by the rest of the characters, Sancho and a badly wounded Don Quixote finally return again to their village.

After being in bed for several days, Don Quixote’s final hour arrives. He decides to abandon his existence as Don Quixote for good, giving up his literary identity and physically dying. He leaves Sancho – his best and most faithful reader – in tears, and avoids further additions by any future imitators by dying.

The original unreliable narrator

The narrator of Part I’s prologue claims to write a sincere and uncomplicated story. Nothing is further from reality. Distancing himself from textual authority, the narrator declares that he merely compiled a manuscript translated by some Arab historian – an untrustworthy source at the time. The reader has to decide what’s real and what’s not.

Don Quixote is also a book made of preexisting books. Don Quixote is obsessed with chivalric romances, and includes episodes parodying other narrative subgenres such as pastoral romances, picaresque novels and Italian novellas (of which Cervantes himself wrote a few).

Don Quixote’s transformation from nobleman to knight-errant is particularly profound given the events in Europe at the time the novel was published. Spain had been reconquered by Christian royals after centuries of Islamic presence. Social status, ethnicity and religion were seen as determining a person’s future, but Don Quixote defied this. “I know who I am,” he answered roundly to whoever tried to convince him of his “true” and original identity.

Don Quixote through the ages

Many writers have been inspired by Don Quixote: from Goethe, Stendhal, Melville, Flaubert and Dickens, to Borges, Faulkner and Nabokov.

In fact, for many critics, the whole history of the novel could justifiably be considered “a variation of the theme of Don Quixote”. Since its early success, there have also been many valuable English translations of the novel. John Rutherford and more recently Edith Grossman have been praised for their versions.

Apart from literature, Don Quixote has inspired many creative works. Based on the episode of the wedding of Camacho in Part II, Marius Petipa choreographed a ballet in 1896. Also created for the stage, Man of La Mancha, the 1960s’ Broadway musical, is one of the most popular reimaginings. In 1992, the State Spanish TV launched a highly successful adaptation of Part I. Terry Gilliam’s much-awaited The Man Who Killed Don Quixote is only the most recent addition to a long list of films inspired by Don Quixote.

More than 400 years after its publication and great success, Don Quixote is widely considered the world’s best book by other celebrated authors. In our own times, full of windmills and giants, Don Quixote’s still-valuable message is that the way we filter reality through any ideology affects our perception of the world.

Excerpt from the “windmill scene” of Don Quixote

Just then, they discovered thirty or forty windmills in that plain. And as soon as don Quixote saw them, he said to his squire: “Fortune is guiding our affairs better than we could have ever hoped. Look over there, Sancho Panza, my friend, where there are thirty or more monstrous giants with whom I plan to do battle and take all their lives, and with their spoils we’ll start to get rich. This is righteous warfare, and it’s a great service to God to rid the earth of such a wicked seed.”

“What giants?” said Sancho Panza.

“Those that you see over there,” responded his master, “with the long arms—some of them almost two leagues long.”

“Look, your grace,” responded Sancho, “what you see over there aren’t giants—they’re windmills; and what seems to be arms are the sails that rotate the millstone when they’re turned by the wind.”

“It seems to me,” responded don Quixote, “that you aren’t well-versed in adventures—they are giants; and if you’re afraid, get away from here and start praying while I go into fierce and unequal battle with them.”

And saying this, he spurred his horse Rocinante without heeding what his squire Sancho was shouting to him, that he was attacking windmills and not giants. But he was so certain they were giants that he paid no attention to his squire Sancho’s shouts, nor did he see what they were, even though he was very close. Rather, he went on shouting: “Do not flee, cowards and vile creatures, for it’s just one knight attacking you!”

At this point, the wind increased a bit and the large sails began to move, which don Quixote observed and said: “Even though you wave more arms than Briaræus, you’ll have to answer to me.”

When he said this—and commending himself with all his heart to his lady Dulcinea, asking her to aid him in that peril, well-covered by his shield, with his lance on the lance rest —he attacked at Rocinante’s full gallop and assailed the first windmill he came to. He gave a thrust into the sail with his lance just as a rush of air accelerated it with such fury that it broke the lance to bits, taking the horse and knight with it, and tossed him rolling onto the ground, very battered.

Sancho went as fast as his donkey could take him to help his master, and when he got there, he saw that don Quixote couldn’t stir—such was the result of Rocinante’s landing on top of him. “God help us,” said Sancho. “Didn’t I tell you to watch what you were doing; that they were just windmills, and that only a person who had windmills in his head could fail to realize it?”

“Keep still, Sancho, my friend,” responded don Quixote. “Things associated with war, more than others, are subject to continual change. Moreover, I believe—and it’s true—that the sage Frestón—he who robbed me of my library—has changed these giants into windmills to take away the glory of my having conquered them, such is the enmity he bears me. But in the long run, his evil cunning will have little power over the might of my sword.”

“God’s will be done,” responded Sancho Panza.”