John Locke (1637 – 1704)

Locke was an Englishman who, along with Newton, was among the founding figures of the Enlightenment itself. Locke was a great political theorist of the period of the English Civil Wars and Glorious Revolution, arguing that sovereignty was granted by the people to a government but could be revoked if that government violated the laws and traditions of the country. He was also a major advocate for religious tolerance; he was even bold enough to note that people tended to be whatever religion was prevalent in their family and social context, so it was ridiculous for anyone to claim exclusive access to religious truth.

Locke was also the founding figure of Enlightenment educational thought, arguing that all humans are born “blank slates” – Tabula Rasa in Latin – and hence access to the human faculty of reason had entirely to do with the proper education. Cruelty, selfishness, and destructive behavior were because of a lack of education and a poor environment, while the right education would lead anybody and everybody to become rational, reasonable individuals. This idea was hugely inspiring to other Enlightenment thinkers, because it implied that society could be perfected if education was somehow improved and rationalized.

Voltaire (1694 – 1778)

The pen name of François-Marie Arouet, Voltaire was arguably the single most influential figure of the Enlightenment. The greatest novelist, poet, and philosopher of France during the height of the Enlightenment period, Voltaire became famous across Europe for his wit, intelligence, and moral battles against what he perceived as injustice and superstition.

In addition to writing hilarious novellas lambasting everything from Prussia’s obsession with militarism to the idiotic fanaticism of the Spanish Inquisition, Voltaire was well known for publicly intervening against injustice. He wrote essays and articles decrying the unjust punishment of innocents and personally convinced the French king Louis XV to commute the sentences of certain individuals unjustly convicted of crimes. He was also an amateur scientist and philosopher – he wrote many of the most important articles in the “official” handbook of the Enlightenment, the Encyclopedia (described below).

Portrait of Voltaire holding a book.

While he was a tireless advocate of reason and justice, it is also important to note the ambiguities of Voltaire’s philosophy. He was a deep skeptic about human nature, despite believing in the existence and desirability of reason. He acknowledged the power of the ignorance and outmoded traditions to govern human behavior, and he expressed considerable skepticism that society could ever be significantly improved. For example, despite his personal disdain for Christian (especially Catholic) institutions, he noted that “if God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent Him,” because without a religious structure shoring up their morality, the ignorant masses would descend into violence and barbarism.

Emilie de Châtelet (1706 – 1749)

A major scientist and philosopher of the period, Châtelet published works on subjects as diverse as physics, mathematics, the Bible, and the very nature of happiness. Perhaps her best-known work during her lifetime was an annotated translation of Newton’s Mathematical Principles, which explained the Newtonian concepts to her (French) readers. Despite the gendered biases of most of her scientific contemporaries, she was accepted as an equal member of the “republic of science.” In Châtelet the link between the legacy of the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment is clearest: while her companion (and lover) Voltaire was keenly interested in science and engaged in modest efforts at his own experiments, Châtelet was a full-fledged physicist and mathematician.

The Encyclopedia of Diderot and D’Alembert (1751)

The brainchild of two major French philosophes, the Encyclopedia was a full-scale attempt to catalog, categorize, and explain all of human knowledge. While its co-inventors, Jean le Rond D’Alembert and Denis Diderot, themselves wrote many of the articles, the majority were written by other philosophes, including (as noted above) Voltaire. The first volume was published in 1751, with other volumes following. In the end the Encyclopedia consisted of 28 volumes containing 60,000 articles with 2,885 illustrations. While its volumes were far too expensive for most of the reading public to access directly, pirated chapters ensured that its ideas reached a much broader audience.

Technical diagram of agricultural equipment in one of the volumes of the Encyclopedia.

The Encyclopedia was explicitly organized to refute traditional knowledge, namely that provided by the church and (to a lesser extent) the state. The claim was that the application of reason to any problem could result in its solution. It also attempted to be a technical resource for would-be scientists and inventors, not only describing aspects of science but including detailed technical diagrams of everything from windmills to mines. In short, the Encyclopedia was intended to be a kind of guide to the entire realm of human thought and technique – a cutting-edge description of all of the knowledge a typical philosophe might think necessary to improve the world.

David Hume (1711 – 1776)

Hume was the major philosopher associated with the Scottish Enlightenment, an outpost of the movement centered in the Scottish capital of Edinburgh. Hume was one of the most powerful critics of all forms of organized religion, which he argued smacked of superstition. To him, any religion based on “miracles” was automatically invalid, since miracles do not happen in an orderly universe knowable through science. In fact, Hume went so far to suggest that belief in a God who resembled a kind of omnipotent version of a human being, with a personality, intentions, and emotions, was simply an expression of primitive ignorance and fear early in human history, as people sought an explanation for a bewildering universe.

Hume also expressed enormous contempt for the common people, who were ignorant and susceptible to superstition. Hume is important to consider because he embodied one of the characteristics of the Enlightenment that often seems the most surprising from a contemporary perspective, namely the fact that it did not champion the rights, let alone anything like the right to political expression, of regular people. To a philosopher like Hume, the average commoner (whether a peasant or a member of the poor urban classes) was so mired in ignorance, superstition, and credulity that he or she should be held in check and ruled by his or her betters.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778)

Rousseau was the great contrarian philosophe of the Enlightenment. He rose to prominence by winning an essay contest in 1749, penning a scathing critique of his contemporary French society and claiming that its so-called “civilization” was a corrupt facade that undermined humankind’s natural moral character. He went on to write both novels and essays that attracted enormous attention both in France and abroad, claiming among other things that children should learn from nature by experiencing the world, allowing their natural goodness and character to develop. He also championed the idea that political sovereignty arose from the “general will” of the people in a society, and that citizens in a just society had to be fanatically devoted to both that general will and to their own moral standards (Rousseau claimed, in a grossly inaccurate and anachronistic argument, that ancient Sparta was an excellent model for a truly enlightened and moral polity). Rousseau’s concept of a moralistic, fanatical government justified by a “general will” of the people would go on to become of the ideological bases of the French Revolution that began just a decade after his death.

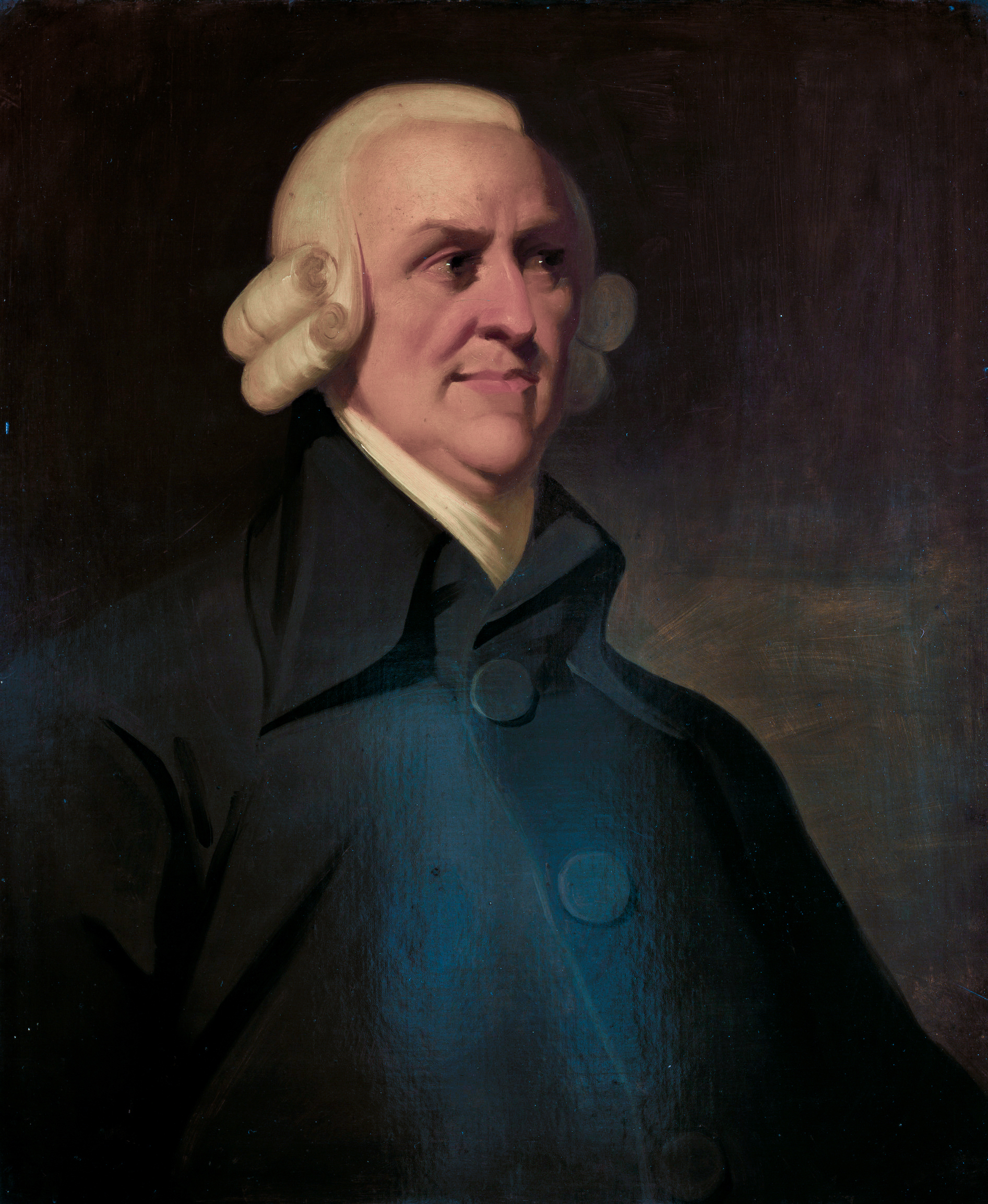

Adam Smith (1723 – 1790)

Smith was another Scotsman who did his work in Edinburgh. He is generally credited with being the first real economist: a social scientist devoted to analyzing how markets function. In his most famous work, The Wealth of Nations, Smith argued that a (mostly) free market, one that operated without the undue interference of the state, would naturally result in never-ending economic growth and nearly universal prosperity. His targets were the monopolies and protectionist taxes and tariffs that limited trade between nations; he argued that if states dropped those kind of burdensome practices, the market itself would increase wealth as if the general prosperity of the nation was lifted by an “invisible hand.”

A sketch of Adam Smith facing to the right

Smith’s importance, besides founding the discipline of economics itself, was that he applied precisely the same kind of Enlightenment ideas and ideals to market exchange as did the other philosophes to morality, science, and so on. Smith, too, insisted that something in human affairs – economics – operated according to rational and knowable laws that could be discovered and explained. His ideas, along with those of David Ricardo, an English economist a generation younger than Smith, are normally considered the founding concepts of “classical” economics.

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804)

Immanuel Kant is the central figure in modern philosophy. He synthesized early modern rationalism and empiricism, set the terms for much of nineteenth and twentieth century philosophy, and continues to exercise a significant influence today in metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, political philosophy, aesthetics, and other fields. The fundamental idea of Kant’s “critical philosophy” – especially in his three Critiques: the Critique of Pure Reason (1781, 1787), the Critique of Practical Reason (1788), and the Critique of the Power of Judgment (1790) – is human autonomy. He argues that the human understanding is the source of the general laws of nature that structure all our experience; and that human reason gives itself the moral law, which is our basis for belief in God, freedom, and immortality. Therefore, scientific knowledge, morality, and religious belief are mutually consistent and secure because they all rest on the same foundation of human autonomy, which is also the final end of nature according to the teleological worldview of reflecting judgment that Kant introduces to unify the theoretical and practical parts of his philosophical system….

Immanuel Kant – Gemaelde 1.jpg

Kant wrote toward the end of the Enlightenment, which was then in a state of crisis. Hindsight enables us to see that the 1780’s was a transitional decade in which the cultural balance shifted decisively away from the Enlightenment toward Romanticism, but of course Kant did not have the benefit of such hindsight….

The problem is that to some it seemed unclear whether [the Enlightenment conception of] progress would in fact ensue if reason enjoyed full sovereignty over traditional authorities; or whether unaided reasoning would instead lead straight to materialism, fatalism, atheism, skepticism, or even libertinism and authoritarianism. The Enlightenment commitment to the sovereignty of reason was tied to the expectation that it would not lead to any of these consequences but instead would support certain key beliefs that tradition had always sanctioned….

Yet the original inspiration for the Enlightenment was the new physics, which was mechanistic. If nature is entirely governed by mechanistic, causal laws, then it may seem that there is no room for freedom, a soul, or anything but matter in motion. This threatened the traditional view that morality requires freedom. We must be free in order to choose what is right over what is wrong, because otherwise we cannot be held responsible. It also threatened the traditional religious belief in a soul that can survive death or be resurrected in an afterlife….

Kant’s main goal is to show that a critique of reason by reason itself, unaided and unrestrained by traditional authorities, establishes a secure and consistent basis for both Newtonian science and traditional morality and religion. In other words, free rational inquiry adequately supports all of these essential human interests and shows them to be mutually consistent. So reason deserves the sovereignty attributed to it by the Enlightenment.

Woman’s Voice at the Age of Enlightenment: Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797)

Mary Wollstonecraft was an English writer, philosopher, and advocate of women’s rights. During her brief career, she wrote novels, treatises, a travel narrative, a history of the French Revolution, a conduct book, and a children’s book. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft’s life, which encompassed an illegitimate child, passionate love affairs, and suicide attempts, received more attention than her writing…. She died at the age of 38, eleven days after giving birth to her second daughter, leaving behind several unfinished manuscripts. The second daughter, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, became an accomplished writer herself as Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein.

After Wollstonecraft’s death, her widower published a memoir (1798) of her life, revealing her unorthodox lifestyle, which inadvertently destroyed her reputation for almost a century. However, with the emergence of the feminist movement at the turn of the twentieth century, Wollstonecraft’s advocacy of women’s equality and critiques of conventional femininity became increasingly important. Today, Wollstonecraft is regarded as one of the founding feminist philosophers, and feminists often cite both her life and work as important influences.

Mary Wollstonecraft by John Opie (c. 1797), National Portrait Gallery, London

Despite the controversial topic, the Rights of Woman received favorable reviews and was a great success. It was almost immediately released in a second edition in 1792, several American editions appeared, and it was translated into French. It was only the later revelations of her personal life that resulted in negative views towards Wollstonecraft, which persisted for over a century.

Education Theory

The majority of Wollstonecraft’s early works focus on education. She assembled an anthology of literary extracts “for the improvement of young women” entitled The Female Reader. In both her conduct book Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787) and her children’s book Original Stories from Real Life (1788), Wollstonecraft advocates educating children into the emerging middle-class ethos of self-discipline, honesty, frugality, and social contentment. Both books also emphasize the importance of teaching children to reason, revealing Wollstonecraft’s intellectual debt to the important 17th-century educational philosopher John Locke. Both texts also advocate the education of women, a controversial topic at the time, and one which she would return to throughout her career. Wollstonecraft argues that well-educated women will be good wives and mothers, and ultimately contribute positively to the nation.

A Vindication of the Rights of Man

Published in response to Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), which was a defense of constitutional monarchy, aristocracy, and the Church of England, and an attack on Wollstonecraft’s friend, Richard Price, Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Man (1790) attacks aristocracy and advocates republicanism. Wollstonecraft attacked not only monarchy and hereditary privilege, but also the gendered language that Burke used to defend and elevate it. Burke associated the beautiful with weakness and femininity, and the sublime with strength and masculinity. Wollstonecraft turns these definitions against him, arguing that his theatrical approach turns Burke’s readers—the citizens—into weak women who are swayed by show. In her first unabashedly feminist critique, Wollstonecraft indicts Burke’s defense of an unequal society founded on the passivity of women.

In her arguments for republican virtue, Wollstonecraft invokes an emerging middle-class ethos in opposition to what she views as the vice-ridden aristocratic code of manners. Influenced by Enlightenment thinkers, she believed in progress, and derides Burke for relying on tradition and custom. She argues for rationality, pointing out that Burke’s system would lead to the continuation of slavery, simply because it had been an ancestral tradition.

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) is one of the earliest works of feminist philosophy. In it, Wollstonecraft argues that women ought to have an education commensurate with their position in society, and then proceeds to redefine that position, claiming that women are essential to the nation because they educate its children and because they could be “companions” to their husbands rather than just wives. Instead of viewing women as ornaments to society or property to be traded in marriage, Wollstonecraft maintains that they are human beings deserving of the same fundamental rights as men. Large sections of the Rights of Woman respond vitriolically to the writers, who wanted to deny women an education.

While Wollstonecraft does call for equality between the sexes in particular areas of life, such as morality, she does not explicitly state that men and women are equal. She claims that men and women are equal in the eyes of God. However, such statements of equality stand in contrast to her statements respecting the superiority of masculine strength and valor. Her ambiguous position regarding the equality of the sexes have since made it difficult to classify Wollstonecraft as a modern feminist. Her focus on the rights of women does distinguish Wollstonecraft from most of her male Enlightenment counterparts. However, some of them, most notably Marquis de Condorcet, expressed a much more explicit position on the equality of men and women. Already in 1790, Condorcet advocated women’s suffrage.

Wollstonecraft addresses her text to the middle class, which she describes as the “most natural state,” and in many ways the Rights of Woman is inflected by a bourgeois view of the world. It encourages modesty and industry in its readers and attacks the uselessness of the aristocracy. But Wollstonecraft is not necessarily a friend to the poor. For example, in her national plan for education, she suggests that, after the age of nine, the poor, except for those who are brilliant, should be separated from the rich and taught in another school.