The term Modernism as a literary term is largely used as a catchall for a global movement that was centered in the United States and Europe, for literature written during the two wars, which is said to be the first industrialized modern period. In another sense, Modernism refers to the general theme: much of the literature of the period is written in reaction to these accelerated times.

Modernism as a literary movement was influenced by thinkers who questioned the certainties that had provided support for traditional modes of social organization, religion, morality, and human identity, or the self. These thinkers included the socialist Karl Marx (1818-1883); Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), whose philosophical studies encouraged accepting concepts as occurring within (and therefore defined by) perspectives, and that critiqued Christianity; Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), who founded psychoanalysis; and Sir James Frazer (1854-1941), who examined mythology and religion syncretically. Modernism rebelled against traditional literary forms and subjects. Modernists subverted basic conventions of prose fiction by breaking up narrative continuity, violating traditional syntax, and disrupting the coherence of narration—through the use of stream-of-consciousness, that is, a narrative style providing the uninterrupted flow of an individual’s thoughts and feelings—among other innovative modes of narration. They also departed from standard ways of representing characters by questioning identity as a real as opposed to an artificial construct, by eliminating the possibility of character coherence, and by conflating characters’ inwardness with their external representation….

Modernist Literature in Great Britain

Although Victorian themes and authors influenced writers like William Butler Yeats (1865-1939), James Joyce (1882- 1941), Virginia Woolf (1882-1941), T. S. Eliot (1888-1965), and D. H. Lawrence (1885-1930), modernism defined itself against Victorianism. Lytton Strachey (1880-1932) in his Eminent Victorians (1918) punctured Victorian stuffiness and pretensions to moral and cultural superiority by critically examining such revered Victorian figures as Henry Edward Manning (1808-1892), a Roman Catholic Cardinal; Florence Nightingale (1820- 1910), the founder of modern nursing; and General Charles George Gordon (1833- 1885), who quelled the Taiping Rebellion. A prominent feature of modernism was its interest in the avant-garde; as Ezra Pound (1885-1972) directed, modernists wanted to make it new.

Joyce in Zürich, c. 1918

Victorian realism gave way to obviously artificial structures. To the modernists, the visible, space, and time are not reality; rather, they are modes through which we apprehend reality. When reviewing Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), T. S. Eliot lauded Joyce’s mythical method in using the paradigm of Ulysses’ journey from Troy to his home in Ithaca to give shape and significance to modern futility and anarchy as Leopold Bloom travels through Dublin. Through this mythical method, writers could be realistic in portraying modern chaos while also suggesting, through psychological insights, a continuing “buried life” (to use Arnold’s phrase) that rises in mythic or archetypal patterns, patterns that express the meeting of mind with nature.

The sense of the individual’s place in the world became tenuous, especially through what modernists identified as the dissociation of the mind and body. Modernists examined this dissociation through such themes as the inorganic and artificial, alienation, and estrangement. While some modernists, like D.H. Lawrence, suggest strategies for reintegrating the body and mind, others, like Virginia Woolf, face this dissociation with a sense of tragedy and overwhelming despair. Another dissociation that modernists pointed to was that between the perceived and the “real” self, between an autonomous self and one created by society and the world. Some writers, like James Joyce, indicated ways to develop a strong individuality that rejected old values and created new ones; others suggested that such a strong individuality can make a world of itself and claim universality; and still others suggested that “real” individuality ceased to exist at all. Such writers considered how individuals could develop “honest” relationships with the world around them.

Modernist Literature in America

After World War I, many writers felt betrayed by the United States, but even more than that, there was a general feeling of change, of progress, of questioning the ways of the past. Throughout the art of this time period, whether it is painting, sculpture, poetry, fiction, or non-fiction, all question the truths of the past, all question the status quo. Largely, this attitude goes hand-in-hand with the disaffection with politics caused by World War I.

Poetry

There is no single style that would encompass all of Modernist poetry; rather, a lot of Modernist poetry could be separated as High Modernism and Low Modernism. These terms are not meant to serve as an aesthetic judgment about the quality of the work, but rather help us understand the range of experimentation occurring during this period. High Modernism features poets who are much more formal, such as T. S. Eliot with his “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” and who look at the modern era as a period of loss, in some ways, looking at how much America has changed and fearing that the change might be for the worse. Essentially, in high modernist works, the authors realize that society has shifted so much, it will never be possible to return to the old ways, so they often represent the world as fragmented, disjointed, or chaotic. High Modernist poetry also maintains a traditional structure and form and often contains explicit allusions to history, myth, or religion, such as the epigraph from Dante’s Inferno which begins T. S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.”

Eliot in 1934 by Lady Ottoline Morrell

Read these excerpts from “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” (1915):

[They will say: “How his hair is growing thin!”]

My morning coat, my collar mounting firmly to the chin,

My necktie rich and modest, but asserted by a simple pin –

[They will say: “But how his arms and legs are thin…! And I have known the eyes already, known them all –

The eyes that fix you in a formulated phrase,

And when I am formulated, sprawling on a pin,

When I am pinned and wriggling on the wall … And I have known the arms already, known them all –

Arms that are braceleted and white and bare

[But in the lamplight, downed with light brown hair!]

It is perfume from a dress

That makes me so digress?

Arms that lie along a table, or wrap about a shawl…. Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach?

I shall wear white flannel trousers, and walk upon the beach.

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each….

Low Modernism is much less formal, experimenting with form. The poetry of William Carlos Williams, the doctor turned poet, is a great example of Low Modernism. His poetry—like “This is Just to Say” and “The Red Wheelbarrow”—often plays with the traditional structure of a poem. These writers tend to be so different that first-time readers often questioned whether these works—Williams’s “This is Just to Say”; Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro”; Cummings’s “In Just”—are poems. Ezra Pound did not even consider himself a poet; rather, in his essay, “A Few Don’ts by an Imagiste,” he refers to himself as an imagiste, or one who creates images.

Read “In Just” by e.e. cumming’s poet (1920):

in Just-

spring when the world is mud-

luscious the little

lame balloonman

whistles far and wee

and eddieandbill come

running from marbles and

piracies and it’s

spring

when the world is puddle-wonderful

the queer

old balloonman whistles

far and wee

and bettyandisbel come dancing

from hop-scotch and jump-rope and

it’s

spring

and

the

goat-footed

balloonMan whistles

far

and

wee

Prose

Experimentation was not limited to Modernist poetry, as prose (fiction and non-fiction) writers were also challenging form, style, and content, that is, what you could or could not write about. Authors such as Faulkner experimented with how to tell a story, especially by using a rotating cast of characters often set in the same county of Yoknapatawpha, while Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons experimented with what exactly was a story. Sherwood Anderson’s book, Winesburg, Ohio, was able to blur the line between short stories and the novel by writing a book of short stories that fit together as a novel. In much the same way, Jean Toomer’s Cane combined poetry, prose, and drama in one strange and beautiful book, foregrounding the dangerous racial politics of the time. Modernist prose was much more than just experimentation, though, in that it also introduced new subject matter. Writers no longer felt the need to veil their opinions; instead, many were explicit in their political critiques. The Great Depression gave rise to Communism among many artists, especially in the works of Ellison and Baldwin, while the Women’s Suffrage Movement highlighted early feminism. Furthermore, the widespread distribution of easily affordable magazines and paperbacks meant that these writers were reaching a wider audience with a more radical message.

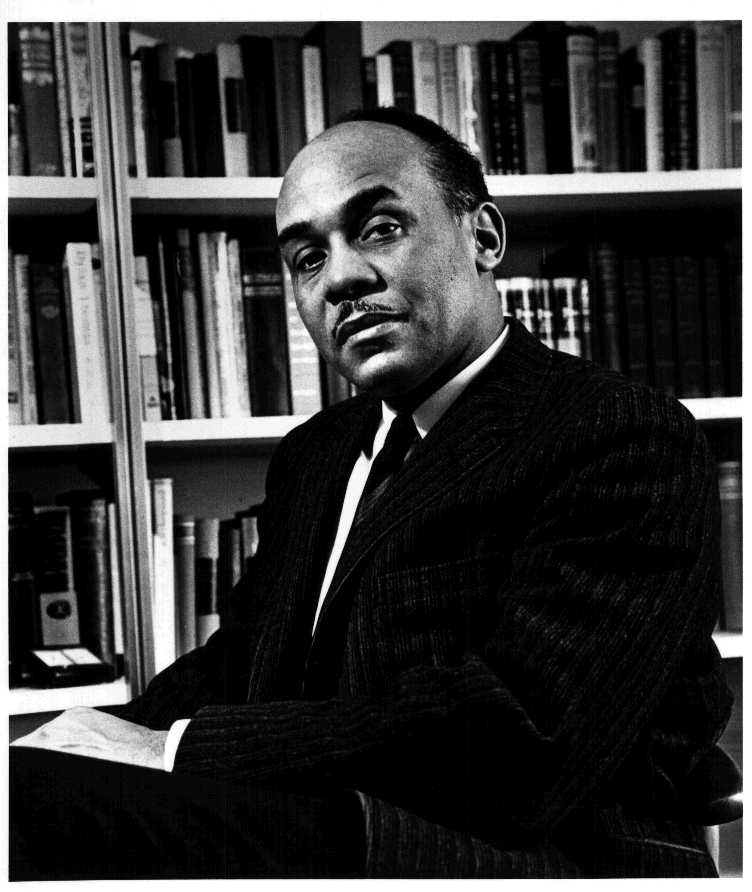

Ralph Ellison, noted author and professor

Read this excerpt from Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952)

I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids – and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination – indeed, everything and anything except me.

Nor is my invisibility exactly a matter of a biochemical accident to my epidermis. That invisibility to which I refer occurs because of a peculiar disposition of the eyes of those with whom I come in contact. A matter of the construction of their inner eyes, those eyes with which they look through their physical eyes upon reality.

Drama

The Modernist period was perhaps the birth of the American playwright. Before Modernism, theater consisted of largely vaudeville or productions of European works. However, the success of Eugene O’Neil paved the way for several other successful American playwrights, such as Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams.

Portrait of O’Neill by Alice Boughton

Experiments in Drama

Although drama had not been a major art form in the 19th century, no type of writing was more experimental than a new drama that arose in rebellion against the glib commercial stage. In the early years of the 20th century, Americans traveling in Europe encountered a vital, flourishing theatre; returning home, some of them became active in founding the Little Theatre movement throughout the country. Freed from commercial limitations, playwrights experimented with dramatic forms and methods of production, and in time producers, actors, and dramatists appeared who had been trained in college classrooms and community playhouses. Some Little Theatre groups became commercial producers—for example, the Washington Square Players, founded in 1915, which became the Theatre Guild (first production in 1919). The resulting drama was marked by a spirit of innovation and by a new seriousness and maturity.

Eugene O’Neill, the most admired dramatist of the period, was a product of this movement. He worked with the Provincetown Players before his plays were commercially produced. His dramas were remarkable for their range. Beyond the Horizon (first performed 1920), Anna Christie (1921), Desire Under the Elms (1924), and The Iceman Cometh (1946) were naturalistic works, while The Emperor Jones (1920) and The Hairy Ape (1922) made use of the Expressionistic techniques developed in German drama in the period 1914–24. He also employed a stream-of-consciousness form of psychological monologue in Strange Interlude (1928) and produced a work that combined myth, family drama, and psychological analysis in Mourning Becomes Electra (1931).

No other dramatist was as generally praised as O’Neill, but many others wrote plays that reflected the growth of a serious and varied drama, including Maxwell Anderson, whose verse dramas have dated badly, and Robert E. Sherwood, a Broadway professional who wrote both comedy (Reunion in Vienna [1931]) and tragedy (There Shall Be No Night [1940]). Marc Connelly wrote touching fantasy in an African American folk biblical play, The Green Pastures (1930). Like O’Neill, Elmer Rice made use of both Expressionistic techniques (The Adding Machine [1923]) and naturalism (Street Scene [1929]). Lillian Hellman wrote powerful, well-crafted melodramas in The Children’s Hour (1934) and The Little Foxes (1939). Radical theatre experiments included Marc Blitzstein’s savagely satiric musical The Cradle Will Rock (1937) and the work of Orson Welles and John Houseman for the government-sponsored Works Progress Administration (WPA) Federal Theatre Project. The premier radical theatre of the decade was the Group Theatre (1931–41) under Harold Clurman and Lee Strasberg, which became best known for presenting the work of Clifford Odets. In Waiting for Lefty (1935), a stirring plea for labour unionism, Odets roused the audience to an intense pitch of fervour, and in Awake and Sing (1935), perhaps the best play of the decade, he created a lyrical work of family conflict and youthful yearning. Other important plays by Odets for the Group Theatre were Paradise Lost (1935), Golden Boy (1937), and Rocket to the Moon (1938). Thornton Wilder used stylized settings and poetic dialogue in Our Town (1938) and turned to fantasy in The Skin of Our Teeth (1942). William Saroyan shifted his lighthearted, anarchic vision from fiction to drama with My Heart’s in the Highlands and The Time of Your Life (both 1939).

Conclusion

Although theirs was a time of great change, the common thread that ties the Modernist writers together—whether they write poetry, prose, or drama—is the techniques they invented. Writers such as Faulkner, whose novel The Sound and the Fury offered an entirely new way to narrate a book, or Langston Hughes, whose poetry blended music and verse, developed entirely new ways of telling a story. Modernist writers radically rejected previous standards in an attempt to “make it new” and, in the process, changed the course of literary history.

Candela Citations

- Writing the Nation: A Concise Introduction to American Literature 1865 to Present. Authored by: Amy Berke, et al.. Provided by: University of North Georgia Press. Located at: https://ung.edu/university-press/_uploads/files/Writing-the-Nation.pdf?t=1510261164762. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- British Literature II: Romantic Era to the Twentieth Century and Beyond. Authored by: Bonnie J. Robinson. Provided by: University of North Georgia Press. Located at: https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1016&context=english-textbooks. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Authored by: Walter Blair, et al.. Provided by: Encyclopedia Britannica Inc.. Located at: https://www.britannica.com/art/American-literature/The-20th-century#ref42272. License: All Rights Reserved

- Joyce in Zurich. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Joyce#/media/File:Revolutionary_Joyce_Better_Contrast.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Eliot in 1934 by Lady Ottoline Morrell. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T._S._Eliot#/media/File:Thomas_Stearns_Eliot_by_Lady_Ottoline_Morrell_(1934).jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Portrait of O'Neill by Alice Boughton. Authored by: Alice Boughton. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eugene_O'Neill#/media/File:ONeill-Eugene-LOC.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Ralph Ellison, noted author and professor. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ralph_Ellison#/media/File:Ralph_Ellison_photo_portrait_seated.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Excerpt from Invisible Man. Authored by: Ralph Ellison. Located at: http://www.umsl.edu/virtualstl/phase2/1950/events/perspectives/documents/invisibleexp.html. Project: Virtual City Project. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Authored by: T.S. Eliot. Provided by: bartleby. Located at: https://www.bartleby.com/198/1.html. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- In Just. Authored by: e.e. cummings. Provided by: Poetry Foundation. Located at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47247/in-just. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright