Modernism in the 20th Century

The world was engaged in world war and localized civil wars in the early part of the 20th century, generating a turbulent time for art. Established territories were realigned, only to be redefined again after the second world war. The 20th-century modern art movement was a liberation of communication in art, depicting art as what ‘you don’t’ see instead of the reality right in front of you. Modern art became a ‘free for all,’ artists were free to use any color to represent anything; the object of modern art was to paint an interpretation instead of authenticity. Distortion of people and objects became the artistic, political statement and emphasized the abnormal. Evolving on the heels of the Post-impressionism movement, which had liberated art from the traditional rules, the philosophy driving the modern art movement was the spirit of experimentation and innovation.

It was a time of experimentation, and artists used wild brush strokes, vibrant colors, overlapping lines, and unnatural positions, all abstracted into a painting. Artists tried to invoke emotions instead of realistic images. Materials moved beyond paint and canvas, introducing the concept of collage, adding fragmented pieces of paper or other material producing a layered look. Out of the industrial revolution came synthetic plastics bringing new chemicals to produce dyes, paper, textiles, and architectural constructions.

In painting, during the 1920s and the 1930s and the Great Depression, modernism is defined by Surrealism, late Cubism, Bauhaus, De Stijl, Dada, German Expressionism, and Modernist and masterful color painters like Henri Matisse as well as the abstractions of artists like Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky, which characterized the European art scene. In Germany, Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, George Grosz, and others politicized their paintings, foreshadowing the coming of World War II, while in America, modernism is seen in the form of American Scene painting and the social realism and regionalism movements that contained both political and social commentary dominated the art world.

American Modernism

American modernism was a cultural movement in the United States, showing both progressive transformation and optimism in the future. It is a reflection of life in America during the 20th century and the continuing socially climbing middle class. Modernism was all about life in the new century, modern art, modern sculpture, and modern architecture, all supporting life in the modern world.

The Girl at a Sewing Machine, painted by Edward Hopper (1882-1967), an American realist, is an iconic genre scene where Hopper rendered his reflection of modern life in America. Born in New York and traveling to Europe, influenced by the great painters of the impressionism and post-impressionism periods…. His art borders on sadness, generated by the loneliness of the scene. Most of Hopper’s paintings are at night, when few are out, increasing the sense of solitude. In the painting, the faces are hidden and emotionless, heightening the feeling of loneliness.

Painting the American dream mural for a department store in the mid-west, Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975), used a mythological analogy and intense colors to depict the story. The twenty-two-foot mural, Achelous and Hercules was a post-war depiction of how a bountiful agricultural society, represented by the power and strength of the two Greeks, can harness the flooding rivers (the bull) to produce food. The story is the origin of the cornucopia, a symbol of cultivated abundance.

European Modernism

Some European Modernists questioned the elitism of the art world, which had always dictated the separation of common, everyday experience from the rarefied, contemplative realm of artistic creation. Of equal importance, their work highlighted—and separated—the role of technical skill from art-making.

Cubism

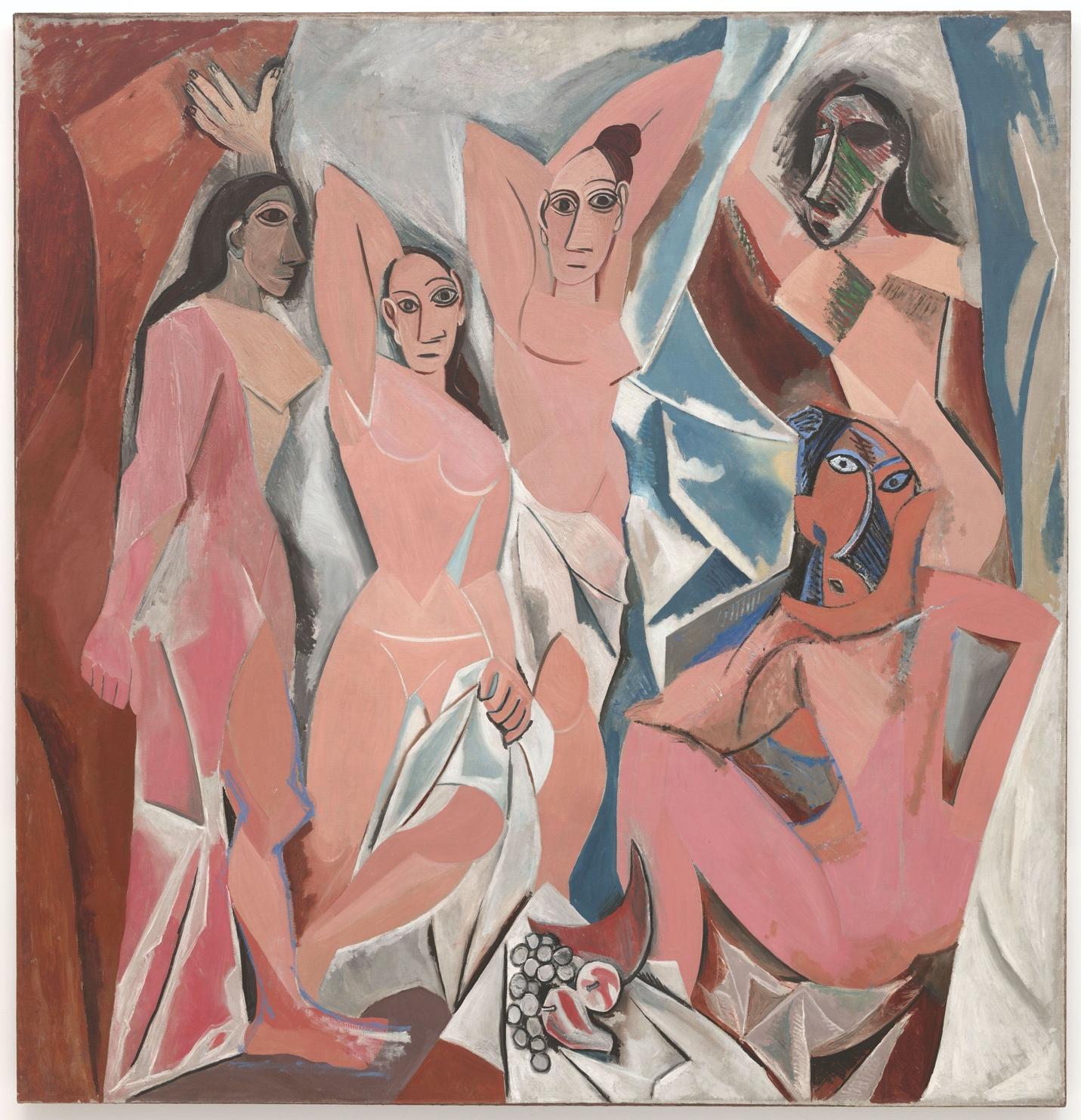

Starting around 1907 and peaking in 1914, Cubism was one of the most important art movements of the 20th century, still influencing artists today. At the turn of the 20th century, political, social, and innovations continued to change daily, and artists began to paint in a new style to reflect the struggles of life in the world around them, painting two-dimensional styles with cubes from multiple perspectives and giving the movement its name. Cubist artists painted the essence of their subjects in fragmented pieces forming multiple perspectives in one painting.

The father of Cubism is Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), yet in his first years of painting, he created works in a naturalistic manner, similar to other artists at the time. Au Lapin Agile (1905) is an iconic painting of the Bohemian life in Paris at the turn of the century.

Au Lapin Agile (At the Lapin Agile), oil on canvas, 99.1 x 100.3 cm (39 x 39 1/2 in.)

The Girl with a Mandolin is noted for the progressive elimination of a subject and pushing the boundaries of abstraction. The color palette is subdued, and he uses monochromatic colors for depth. In 1910, the painting approached the apex of the cubism period and was rectangles, squares, and circles. The Cubist period opened the door for abstracted geometric forms. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was a monumental change from the traditional depiction of females as he painted the flat, splintered figures all compressed into a small overlapping space.

Dada or Dadaism

Dada was an art movement of the European avant-garde in the early 20th century, with early centers in Zürich, Switzerland and in New York. Developed in reaction to World War I, the Dada movement consisted of artists who rejected the logic, reason, and aestheticism of modern capitalist society, instead expressing nonsense, irrationality, and anti-bourgeois protest in their works. The art of the movement spanned visual, literary, and sound media, including collage, sound poetry, cut-up writing, and sculpture. Dadaist artists expressed their discontent with violence, war, and nationalism, and maintained political affinities with the radical left.

The roots of Dada lay in pre-war avant-garde. The term anti-art, a precursor to Dada, was coined by Marcel Duchamp around 1913 to characterize works which challenge accepted definitions of art. Cubism and the development of collage and abstract art would inform the movement’s detachment from the constraints of reality and convention. The work of French poets, Italian Futurists and the German Expressionists would influence Dada’s rejection of the tight correlation between words and meaning.

The Dadaist movement included public gatherings, demonstrations, and publication of art/literary journals; passionate coverage of art, politics, and culture were topics often discussed in a variety of media. Key figures in the movement included Hugo Ball, Marcel Duchamp, Emmy Hennings, Hans Arp, Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, Francis Picabia, George Grosz, Man Ray, Beatrice Wood, Kurt Schwitters, Hans Richter, and Max Ernst, among others. The movement influenced later styles like the avant-garde and downtown music movements, and groups including surrealism and pop art.

‘Fountain’ by Marcel Duchamp (replica), Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

Perhaps the most famous work of Dada art is Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, one of his “readymades” (everyday objects found or purchased and declared art) such as a bottle rack, and was active in the Society of Independent Artists. In 1917 he submitted the now famous Fountain, a urinal signed R. Mutt, to the Society of Independent Artists exhibition only to have the piece rejected. First an object of scorn within the arts community, the Fountain has since become almost canonized by some as one of the most recognizable modernist works of sculpture. Art world experts polled by the sponsors of the 2004 Turner Prize, Gordon’s gin, voted it “the most influential work of modern art.” As recent scholarship documents, the work is likely more collaborative than it has been given credit for in twentieth-century art history. Duchamp indicates in a 1917 letter to his sister that a female friend was centrally involved in the conception of this work. As he writes: “One of my female friends who had adopted the pseudonym Richard Mutt sent me a porcelain urinal as a sculpture.”

Surrealism

One of the most important and subversive movements of the twentieth century, Surrealism flourished particularly in the 1920s and 1930s and provided a radical alternative to the rational and formal qualities of Cubism. Unlike Dada, from which in many ways it sprang, it emphasized the positive, rather than the pessimistic rejection of earlier traditions.

Alberto Giacometti, The Palace at 4 a.m., 1932. Wood, glass, wire, and string, 25 x 28-1/4 x 15-3/4 inches (The Museum of Modern Art)

Surrealism sought access to the subconscious and to translate this flow of thought into terms of art. Originally a literary movement, it was famously defined by the poet André Breton in the First Manifesto of Surrealism (1924):

SURREALISM, noun, masc. Pure psychic automatism by which it is intended to express either verbally or in writing the true function of thought. Thought dictated in the absence of all control exerted by reason, and outside all aesthetic or moral preoccupations.

A number of distinct strands can be discerned in the visual manifestation of Surrealism. Artists such as Max Ernst and André Masson favoured automatism in which conscious control is suppressed and the subconscious is allowed to take over. Conversely, Salvador Dali and René Magritte pursued an hallucinatory sense of super-reality in which the scenes depicted make no real sense. A third variation was the juxtaposition of unrelated items, setting up a startling unreality outside the bounds of normal reality.

Common to all Surrealistic enterprises was a post-Freudian desire to set free and explore the imaginative and creative powers of the mind. Surrealism was originally Paris based. Its influence spread through a number of journals and international exhibitions, the most important examples of the latter being the International Surrealist Exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries, London and the Fantastic Art Dada, Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, both held in 1936.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, the centre of Surrealist activity transferred to New York and by the end of the War the movement had lost its coherence. It has retained a potent influence, however, clearly evident in aspects of Abstract Expressionism and various other artistic manifestations of the second half of the twentieth century.

Abstract Expressionism

Abstract expressionism was an American post–World War II art movement that can be thought of a bridge between modern and postmodern painting (around 1960). Although it is true that spontaneity or the impression of spontaneity characterized many of the abstract expressionists’ works, in reality most of these paintings involved careful planning, especially since their large size demanded it. In many instances, abstract art implied the expression of ideas that concern the spiritual, the unconscious, and the mind.

As the term suggests, the work was characterized by highly abstract or non-objective imagery that appeared emotionally charged with personal meaning. The artists, however, rejected these implications of the name. They insisted their subjects were not “abstract,” but rather primal images, deeply rooted in society’s collective unconscious. Their paintings did not express mere emotion. They communicated universal truths about the human condition

Barnett Newman wrote:

We felt the moral crisis of a world in shambles, a world destroyed by a great depression and a fierce World War, and it was impossible at that time to paint the kind of paintings that we were doing—flowers, reclining nudes, and people playing the cello.[1]

Although distinguished by individual styles, the Abstract Expressionists shared common artistic and intellectual interests. While not expressly political, most of the artists held strong convictions based on Marxist ideas of social and economic equality. Many had benefited directly from employment in the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project. There, they found influences in Regionalist styles of American artists such as Thomas Hart Benton, as well as the Socialist Realism of Mexican muralists including Diego Rivera and José Orozco….

Whereas Surrealism had found inspiration in the theories of Sigmund Freud, the Abstract Expressionists looked more to the Swiss psychologist Carl Jung and his explanations of primitive archetypes that were a part of our collective human experience. They also gravitated toward Existentialist philosophy, made popular by European intellectuals such as Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre.

Given the atrocities of World War II, Existentialism appealed to the Abstract Expressionists. Sartre’s position that an individual’s actions might give life meaning suggested the importance of the artist’s creative process. Through the artist’s physical struggle with his materials, a painting itself might ultimately come to serve as a lasting mark of one’s existence. Each of the artists involved with Abstract Expressionism eventually developed an individual style that can be easily recognized as evidence of his artistic practice and contribution.

Jackson Pollock’s energetic action paintings (such as No. 5 on the left), with their busy feel, are different both technically and aesthetically from the violent and grotesque Women series of Willem de Kooning Woman V on the right). In contrast to the emotional energy and gestural surface marks of Pollock and de Kooning, the color-field painters initially appeared to be cool and austere, eschewing the individual mark in favor of large, flat areas of color, which these artists considered to be the essential nature of visual abstraction, along with the actual shape of the canvas.

Postmodern-Contemporary Art

Postmodernism (also known as post-structuralism ) is skeptical of explanations that claim to be valid for all groups, cultures, traditions, or races, and instead focuses on the relative truths of each person (i.e. postmodernism = relativism). In the postmodern understanding, interpretation is everything; reality only exists through our interpretations of what the world means to us individually. Postmodernism relies on concrete experience over abstract principles, arguing that the outcome of one’s own experience will necessarily be fallible and relative rather than certain or universal…. Postmodernism frequently serves as an ambiguous, overarching term for skeptical interpretations of culture, literature, art, philosophy, economics, architecture, fiction, and literary criticism….

Postmodernism postulates that many, if not all, apparent realities are only social constructs and therefore subject to change. It claims that there is no absolute truth and that the way people perceive the world is subjective and emphasizes the role of language, power relations, and motivations in the formation of ideas and beliefs. In particular, it attacks the use of binary classifications such as male versus female, straight versus gay, white versus black, and imperial versus colonial; it holds realities to be plural, relative, and dependent on who the interested parties are and the nature of these interests. Postmodernist approaches consider that the ways in which social dynamics, such as power and hierarchy, affect human conceptualizations of the world have important effects on the way knowledge is constructed and used. Postmodernist thought often emphasizes constructivism, idealism, pluralism, relativism, and skepticism in its approaches to knowledge and understanding.

“Getting” Contemporary Art

It’s ironic that many people say they don’t “get” contemporary art because, unlike Egyptian tomb painting or Greek sculpture, art made since 1960 reflects our own recent past. It speaks to the dramatic social, political and technological changes of the last fifty years, and it questions many of society’s values and assumptions—a tendency of postmodernism, a concept sometimes used to describe contemporary art. What makes today’s art especially challenging is that, like the world around us, it has become more diverse and cannot be easily defined through a list of visual characteristics, artistic themes or cultural concerns.

Minimalism and Pop Art, two major art movements of the early 1960s, offer clues to the different directions of art in the late 20th and 21st century. Both rejected established expectations about art’s aesthetic qualities and need for originality. Minimalist objects are spare geometric forms, often made from industrial processes and materials, which lack surface details, expressive markings, and any discernible meaning. Pop Art took its subject matter from low-brow sources like comic books and advertising. Like Minimalism, its use of commercial techniques eliminated emotional content implied by the artist’s individual approach, something that had been important to the previous generation of modern painters. The result was that both movements effectively blurred the line distinguishing fine art from more ordinary aspects of life, and forced us to reconsider art’s place and purpose in the world.

Shifting Strategies

Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Cans, 1962, synthetic polymer paint on 32 canvases, each 20 x 16″ (The Museum of Modern Art) (photo: Steven Zucker)

Minimalism and Pop Art paved the way for later artists to explore questions about the conceptual nature of art, its form, its production, and its ability to communicate in different ways. In the late 1960s and 1970s, these ideas led to a “dematerialization of art,” when artists turned away from painting and sculpture to experiment with new formats including photography, film and video, performance art, large-scale installations and earth works. Although some critics of the time foretold “the death of painting,” art today encompasses a broad range of traditional and experimental media, including works that rely on Internet technology and other scientific innovations.

Popular culture, “popular” art

At first glance, Pop Art might seem to glorify popular culture by elevating soup cans, comic strips and hamburgers to the status of fine art on the walls of museums. But, then again, a second look may suggest a critique of the mass marketing practices and consumer culture that emerged in the United States after World War II. Andy Warhol’s Gold Marilyn Monroe (1962) clearly reflects this inherent irony of Pop. The central image on a gold background evokes a religious tradition of painted icons, transforming the Hollywood starlet into a Byzantine Madonna that reflects our obsession with celebrity. Notably, Warhol’s spiritual reference was especially poignant given Monroe’s suicide a few months earlier. Like religious fanatics, the actress’s fans worshipped their idol; yet, Warhol’s sloppy silk-screening calls attention to the artifice of Marilyn’s glamorous façade and places her alongside other mass-marketed commodities like a can of soup or a box of Brillo pads.

Andy Warhol, Gold Marilyn Monroe, 1962, silkscreen on canvas,

6′ 11 1/4″ x 57″ (211.4 x 144.7 cm) (Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Richard Hamilton, Just what is it that makes today’s home so different, so appealing?,

1956, collage, 26 cm × 24.8 cm (10.25 in × 9.75 in)

(Kunsthalle Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany)

Genesis of Pop

In this light, it’s not surprising that the term “Pop Art” first emerged in Great Britain, which suffered great economic hardship after the war. In the late 1940s, artists of the “Independent Group,” first began to appropriate idealized images of the American lifestyle they found in popular magazines as part of their critique of British society. Critic Lawrence Alloway and artist Richard Hamilton are usually credited with coining the term, possibly in the context of Hamilton’s famous collage from 1956. Just what is it that makes today’s home so different, so appealing? Made to announce the Independent Group’s 1956 exhibition “This Is Tomorrow,” in London, the image prominently features a muscular semi-nude man, holding a phallically positioned Tootsie Pop.

Robert Rauschenberg, Bed, 1955, oil and pencil on pillow, quilt, and sheet on wood supports,

191.1 x 80 x 20.3 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Pop Art’s origins, however, can be traced back even further. In 1917, Marcel Duchamp asserted that any object—including his notorious example of a urinal—could be art, as long as the artist intended it as such. Artists of the 1950s built on this notion to challenge boundaries distinguishing art from real life, in disciplines of music and dance, as well as visual art. Robert Rauschenberg’s desire to “work in the gap between art and life,” for example, led him to incorporate such objects as bed pillows, tires and even a stuffed goat in his “combine paintings” that merged features of painting and sculpture. Likewise, Claes Oldenberg created The Store, an installation in a vacant storefront where he sold crudely fashioned sculptures of brand-name consumer goods. These “Proto-pop” artists were, in part, reacting against the rigid critical structure and lofty philosophies surrounding Abstract Expressionism, the dominant art movement of the time; but their work also reflected the numerous social changes taking place around them.

Post-War Consumer Culture Grabs Hold (and Never Lets Go)

1950s Advertisement for the American Gas Association

The years following World War II saw enormous growth in the American economy, which, combined with innovations in technology and the media, spawned a consumer culture with more leisure time and expendable income than ever before. The manufacturing industry that had expanded during the war now began to mass-produce everything from hairspray and washing machines to shiny new convertibles, which advertisers claimed all would bring ultimate joy to their owners. Significantly, the development of television, as well as changes in print advertising, placed new emphasis on graphic images and recognizable brand logos—something that we now take for granted in our visually saturated world.

It was in this artistic and cultural context that Pop artists developed their distinctive style of the early 1960s. Characterized by clearly rendered images of popular subject matter, it seemed to assault the standards of modern painting, which had embraced abstraction as a reflection of universal truths and individual expression.

Irony and Iron-Ons

(L) Roy Lichtenstein, Girl with a Ball, 1961, oil on canvas, 60 1/4 x 36 1/4″ (153 x 91.9 cm)

(Museum of Modern Art, New York);

(R) Detail of face showing Lichtenstein’s painted Benday dots)

In contrast to the dripping paint and slashing brushstrokes of Abstract Expressionism—and even of Proto-Pop art—Pop artists applied their paint to imitate the look of industrial printing techniques. This ironic approach is exemplified by Lichtenstein’s methodically painted Benday dots, a mechanical process used to print pulp comics.

As the decade progressed, artists shifted away from painting towards the use of industrial techniques. Warhol began making silkscreens, before removing himself further from the process by having others do the actual printing in his studio, aptly named “The Factory.” Similarly, Oldenburg abandoned his early installations and performances, to produce the large-scale sculptures of cake slices, lipsticks, and clothespins that he is best known for today.

Contemporary artists continue to use a varied vocabulary of abstract and representational forms to convey their ideas. It is important to remember that the art of our time did not develop in a vacuum; rather, it reflects the social and political concerns of its cultural context. For example, artists like Judy Chicago, who were inspired by the feminist movement of the early 1970s, embraced imagery and art forms that had historical connections to women.

The Dinner Party, art installation by Judy Chicago, installed at the Elizabeth A Sackler Center for Feminist Art in the Brooklyn Museum in Brooklyn, NY

In the 1980s, artists appropriated the style and methods of mass media advertising to investigate issues of cultural authority and identity politics. More recently, artists like Maya Lin (Sculpture made of multiple wood 2×4 pieces on the left), who designed the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial Wall in Washington D.C., and Richard Serra (Tilted Spheres on the right), who was loosely associated with Minimalism in the 1960s, have adapted characteristics of Minimalist art to create new abstract sculptures that encourage more personal interaction and emotional response among viewers.

These shifting strategies to engage the viewer show how contemporary art’s significance exists beyond the object itself. Its meaning develops from cultural discourse, interpretation and a range of individual understandings, in addition to the formal and conceptual problems that first motivated the artist. In this way, the art of our times may serve as a catalyst for an on-going process of open discussion and intellectual inquiry about the world today.

Postmodernist Sculpture

The characteristics of postmodernism, such as collage, pastiche, appropriation, and the destruction of barriers between fine art and popular culture, can be applied to sculptural works.

The characteristics of postmodernism, including bricolage, collage, appropriation, the recycling of past styles and themes in a modern-day context, and destruction of the barriers between fine arts, craft and popular culture, can be applied to sculpture. While inherently difficult to define by nature, postmodernism began with pop art and continued within many following movements including conceptual art, neo-expressionism, feminist art, and the young British artists of the 1990s. The plurality of idea and form that defines postmodernism essentially allow any medium to be considered postmodern. In terms of sculpture, characteristics like mixed media, installation art, conceptual art, video light art, and sound art are often regarded as postmodern.

Typewriter Eraser by Claes Oldenburg, 1999: Claes Oldenburg is known for memorializing everyday objects in his works, challenging the idea that public monuments must commemorate historical figures or events.