Greek Drama

The theatrical culture of ancient Greece flourished from approximately 700 BCE onward. The city-state of Athens was the center of cultural power during this period and held a drama festival in honor of the god Dionysus, called the Dionysia. This festival was exported to many of Athens’ numerous colonies to promote a common cultural identity across the empire. Two dramatic genres to emerge from this era of Greek theater were tragedy and comedy, both of which rose to prominence around 500-490 BCE.

The creation of drama emerged from the worship of the gods. Specifically, the celebrations of the god Dionysus, god of wine and revelry, brought about the first recognizable “plays” and “actors.” Not surprisingly, religious festivals devoted to Dionysus involved a lot of celebrating, and part of that celebration was choruses of singing and chanting. Greek writers started scripting these performances, eventually creating what we now recognize as plays. A prominent feature of Greek drama left over from the Dionysian rituals remained the chorus, a group of performers who chanted or sang together and served as the narrator to the stories depicted by the main characters.

Greek drama depicted life in human terms, even when using mythological or ancient settings. Playwrights would set their plays in the past or among the gods, but the experiences of the characters in the plays were recognizable critiques of the playwrights’ contemporary society. Among the most powerful were the tragedies: stories in which the frailty of humanity, most importantly the problem of pride, served to undermine the happiness of otherwise powerful individuals. Typically, in a Greek tragedy, the main character is a powerful male leader, a king or a military captain, who enjoys great success in his endeavors until a fatal flaw of his own personality and psyche causes him to do something foolish and self-destructive. Very often this took the form of hubris, overweening pride and lack of self-control, which the Greeks believed was offensive to the gods and could bring about divine retribution. Other tragedies emphasized the power of fate, when cruel circumstances conspired to lead even great heroes to failure….

Greek drama, both tragedy and comedy, is of enormous historical importance because even when it used the gods as characters or fate as an explanation for problems, it put human beings front and center in being responsible for their own errors. It depicted human choice as being the centerpiece of life against a backdrop of often uncontrollable circumstances. Tragedy gave the Greeks the option of lamenting that condition, while comedy offered the chance of laughing at it. In the surviving plays of the ancient Greeks, there were very few happy endings, but plenty of opportunities to relate to the fate of, or make fun of, the protagonists. In turn, almost every present-day movie and television show is deeply indebted to Greek drama. Greek drama was the first time human beings acted out stories that were meant to entertain, and sometimes to inform, their audiences.

Greek Tragedy

Sometimes referred to as Attic tragedy, Greek tragedy is an extension of the ancient rites carried out in honor of Dionysus, and it heavily influenced the theater of ancient Rome and the Renaissance. Tragic plots were often based upon myths from the oral traditions of archaic epics, and took the form of narratives presented by actors. Tragedies typically began with a prologue, in which one or more characters introduce the plot and explain the background to the ensuing story. The prologue is then followed by paraodos, after which the story unfolds through three or more episodes. The episodes are interspersed by stasima, or choral interludes that explain or comment on the situation that is developing. The tragedy then ends with an exodus, which concludes the story.

Aeschylus and the Codification of Tragic Drama

Aeschylus was the first tragedian to codify the basic rules of tragic drama. He is often described as the father of tragedy. He is credited with inventing the trilogy, a series of three tragedies that tell one long story. Trilogies were often performed in sequence over the course of a day, from sunrise to sunset. At the end of the last play, a satyr play was staged to revive the spirits of the public after they had witnessed the heavy events of the tragedy that had preceded it.

Marble bust of Aeschylus.

According to Aristotle, Aeschylus also expanded the number of actors in theater to allow for the dramatization of conflict on stage. Previously, it was standard for only one character to be present and interact with the homogeneous chorus, which commented in unison on the dramatic action unfolding on stage. Aeschylus’s works show an evolution and enrichment in dialogue, contrasts, and theatrical effects over time, due to the rich competition that existed among playwrights of this era. Unfortunately, his plays, and those of Sophocles and Euripides, are the only works of classical Greek literature to have survived mostly intact, so there are not many rival texts to examine his works against.

The Reforms of Sophocles

Cast of Sophocles’ bust in the Pushkin Museum.

Sophocles was one such rival who triumphed against the famous and previously unchallenged Aeschylus. Sophocles introduced a third actor to staged tragedies, increased the chorus to 15 members, broke the cycle of trilogies (making possible the production of independent dramas), and introduced the concept of scenery to theater. Compared to the works of Aeschylus, choruses in Sophocles’ plays did less explanatory work, shifting the focus to deeper character development and staged conflict. The events that took place were often left unexplained or unjustified, forcing the audience to reflect upon the human condition.

The Realism of Euripides

Euripides differs from Aeschylus and Sophocles in his search for technical experimentation and increased focus on feelings as a mechanism to elaborate the unfolding of tragic events. In Euripides’ tragedies, there are three experimental aspects that reoccur. The first is the transition of the prologue to a monologue performed by an actor informing spectators of a story’s background. The second is the introduction of deus ex machina, or a plot device whereby a seemingly unsolvable problem is suddenly and abruptly resolved by the unexpected intervention of some new event, character, ability, or object. Finally, the use of a chorus was minimized in favor of a monody sung by the characters.

Statue of Euripides.

Another novelty introduced by Euripidean drama is the realism with which characters’ psychological dynamics are portrayed. Unlike in Aeschylus or Sophocles’ works, heroes in Euripides’ plays were portrayed as insecure characters troubled by internal conflict rather than simply resolute. Female protagonists were also used to portray tormented sensitivity and irrational impulses that collided with the world of reason.

Greek Comedy

In addition to tragedy, the Greeks invented comedy. The essential difference is that tragedy revolves around pathos, or suffering, from which the English word “pathetic” derives. Pathos is meant to inspire sympathy and understanding in the viewer. Watching a Greek tragedy should, the playwrights hoped, lead the audience to relate to and sympathize with the tragic hero. Comedy, however, is meant to inspire mockery and gleeful contempt of the failings of others, rather than sympathy. The most prominent comic playwright (whose works survive) was Aristophanes, a brilliant writer whose plays are full of lying, hypocritical Athenian politicians and merchants who reveal themselves as the frauds they are to the delight of audiences.

As Aristotle wrote in his Poetics, comedy is defined by the representation of laughable people, and involves some kind of blunder or ugliness that does not cause pain or disaster. Athenian comedy is divided into three periods: Old Comedy, Middle Comedy, and New Comedy. The Old Comedy period is largely represented by the 11 surviving plays of Aristophanes, whereas much of the work of the Middle Comedy period has been lost. New Comedy is known primarily by the substantial papyrus fragments of Menander. In general, the divisions between these periods is largely arbitrary, and ancient Greek comedy almost certainly developed constantly over the years.

Old Comedy and Aristophanes

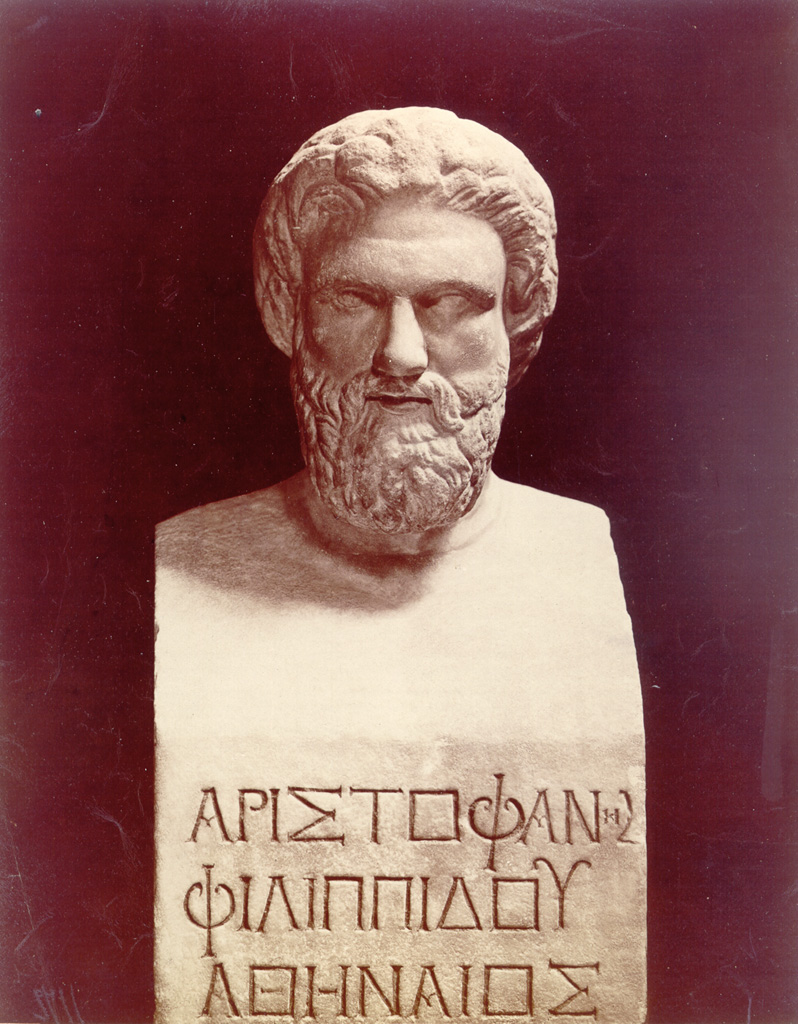

Aristophanes, the most important Old Comic dramatist, wrote plays that abounded with political satire, as well as sexual and scatological innuendo. He lampooned the most important personalities and institutions of his day, including Socrates in The Clouds. His works are characterized as definitive to the genre of comedy even today.

Bust of Aristophanes in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy

One famous play by Aristophanes, Lysistrata, was set in the Peloponnesian War. The women of Athens are fed up with the pointless conflict and use the one thing they have some power over, their bodies, to force the men to stop the fighting by withholding sex. A Spartan contingent appears begging to open peace negotiations because, it turns out, the Spartan women have done the same thing. Here, Aristophanes not only indulged in the ribald humor that was popular with the Greeks (even by present-day standards, Lysistrata is full of “dirty” jokes) but showed a remarkable awareness of, and sympathy for, the social position of Greek women. In fact, in plays like Lysistrata we see evidence that Greek women were not in fact always secluded and rendered mute by male-dominated society, even though (male) Greek commentators generally argued that they should be.

Middle Comedy

Although the line between Old and Middle Comedy is not clearly marked chronologically, there are some important thematic differences between the two. For instance, the role of the chorus in Middle Comedy was largely diminished to the point where it had no influence on the plot. Additionally, public characters were no longer impersonated or personified onstage, and objects of ridicule tended to be more general rather than personal, and in many instances, literary rather than political. For some time, mythological burlesque was popular among Middle Comic poets. Stock characters also were employed during this period. In-depth assessment and critique of the styling of Middle Comedy is difficult, given the lack of complete bodies of work. However, given the revival of this style in Sicily and Magna Graecia, it appears that the works of this period did have considerable widespread literary and social impact.

New Comedy

The style of New Comedy is comparable to what is contemporarily referred to as situation comedy or comedy of manners. The playwrights of Greek New Comedy built upon the devices, characters, and situations their predecessors had developed. Prologues to shape the audience’s understanding of events, messengers’ speeches to announce offstage action, and ex machina endings were all well established tropes that were used in New Comedies. Satire and farce occupied less importance in the works of this time, and mythological themes and subjects were replaced by everyday concerns. Gods and goddesses were, at best, personified abstractions rather than actual characters, and no miracles or metamorphoses occurred. For the first time, love became a principal element in this type of theater.

Three playwrights are well known from this period: Menander, Philemon, and Diphilus. Menander was the most successful of the New Comedians. Menander’s comedies focused on the fears and foibles of the ordinary man, as opposed to satirical accounts of political and public life, which perhaps lent to his comparative success within the genre. His comedies are the first to demonstrate the five-act structure later to become common in modern plays. Philemon’s comedies dwell on philosophical issues, whereas Diphilus was noted for his use of farcical violence.

Candela Citations

- Classical Greek Theater. Authored by: Boundless. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hccc-worldhistory/chapter/classical-greek-theater/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Culture. Authored by: Christopher Brooks. Provided by: LibreTexts. Located at: https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/History/World_History/Book%3A_Western_Civilization_-_A_Concise_History_I_(Brooks)/07%3A_The_Classical_Age_of_Greece/7.02%3A_Culture. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Bust of Aristophanes in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aristophanes#/media/File:Aristofanes.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright