In the late Middle Ages earlier ways of philosophizing were continued and formalized into distinct schools of thought. In the Dominican order, Thomism, the theological and philosophical system of Thomas Aquinas, was made the official teaching, though the Dominicans did not always adhere to it rigorously. Averroism, cultivated by philosophers such as John of Jandun (c. 1286–1328), remained a significant, though sterile, movement into the Renaissance. In the Franciscan order, John Duns Scotus (c. 1266–1308) and William of Ockham (c. 1285–c. 1347) developed new styles of theology and philosophy that vied with Thomism throughout the late Middle Ages.

The Radical Aristotelians

Efforts to incorporate elements of Aristotelian metaphysics within the general scheme of Christian thought continued to stir controversy for a long time. Although Aquinas himself showed great caution in applying the ideas of Ibn Rushd to Christian theology, others were far more daring. Boetius of Dacia, for example, raised serious questions about individual immortality, and Siger of Brabant explicitly declared that human thought occurs only within the context of a comprehensive, single, unified intellect—a notion that would re-emerge during the modern period in the philosophy of Spinoza.

Philosophical dispute about such matters has theological implications, and the church was not reluctant to express its concern. In 1270 Etienne Tempier, the Bishop of Paris (encouraged by Henry of Ghent) issued a formal condemnation of thirteen doctrines held by “radical Aristotelians,” including the unity of intellect, causal necessity, and the eternity of the world. In 1277 he expanded the number of condemned doctrines to 219, this time including on the list some clearly Thomistic teachings on the nature and individuation of substances and the role of reason in knowledge of god. This encouraged the (mostly) neoplatonic Franciscans of the late thirteenth century to pursue their attacks on the Dominican order’s more enthusiastic reliance upon the offensive use of Aristotle. Giles of Rome, with a notable effort to synthesize the chief doctrines of Aquinas with the neoplatonic tradition, was a rare exception.

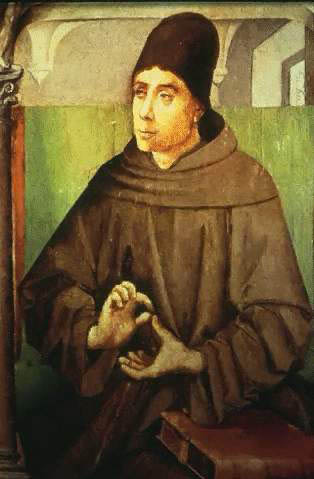

Duns Scotus

In the next generation, John Duns Scotus criticized many of the notions at the heart of the Thomistic philosophy, placing more emphasis on the traditional Augustinian theology in his own subtle and idiosyncratic exposition of a critical metaphysics. Since the natural object of human intellect is Being itself, as comprehended under the universal Forms, sensory information is often a misleading distraction from reality. Thus, the truest knowledge of god and self is to be derived by revelation and reason rather than from experience.

Since he conceived of god as the truest Being, which universally encompasses all of the perfections, Scotus followed Anselm in relying upon the Ontological Argument for god’s existence. Sensory information, excluded from this proof, cannot corrupt or distort its theological and even devotional significance, which establishes the perfect reality and freedom of the divine. Still, Scotus granted that from a common-sense, rational standpoint the more empirical Aristotelian arguments used by Aquinas have the virtue of greater clarity and certainty.

Scotus earned a reputation for great subtlety in reasoning…. Much of this reputation derives from his frequent use of a sophisticated doctrine regarding three different kinds of distinction that may be drawn among things:

- Everyone granted that a real distinction is drawn between genuinely separable things, each of which is capable of existing independently of all others.

- A merely mental (or conceptual) distinction, on the other hand, is drawn wholly within our imaginations, between aspects or descriptions that in fact apply to a single thing.

- Between these extremes, Scotus now added the formal distinction, a genuine, objective difference that holds between things that are inseparable from each other in reality.

Thus, for example, god’s attributes of omnipotence, omniscience, benevolence, and freedom are only formally distinct from each other, as are the concrete particular instantiations of universal Forms. This distinction among distinctions has significant implications for the description of human nature. Scotus conceded to Aquinas the now-standard hylomorphic view of the soul as the form of the human body. But the functions of the soul are formally distinct for Scotus, so that the will can be radically free in its choices, even though the intellect is constrained by the structure of reason and evidence. The immortality of the individual human soul, though not natural in any sense, is guaranteed by the benevolent intervention of god.

William of Ockham

An even more strikingly modern conception of philosophy appeared in the work of William of Ockham, an English Franciscan who represented his Order in major controversies over papal authority and the vow of poverty. Concerned with the possibility that an over-emphasis on universal forms might undermine the theological doctrine of free will, Ockham secured his voluntaristic convictions by mounting a full-scale attack on essentialism.

Thus, Ockham’s metaphysics is thoroughly nominalistic: everything that exists is particular, and relations among these individuals are purely conceptual. Thus, if we see a red shirt and a red car, there is no third thing (the form or essence of Redness) that they share. Between this red button and that red button there is only our own mental act of noticing their resemblance with respect to color. Only concrete individual substances and their particular features are real for Ockham; all else is manufactured by the human mind.

This treatment of the problem of universals is the most notable application of the famous principle of parsimony that came to be known as Ockham’s Razor. Ockham declared that “plurality is not to be posited without necessity.” By this standard, the ontological analysis of any situation should make reference to existing entities only when the features at issue cannot be explained in any other way. Although opinions may differ about whether or not the postulation of a new kind of beings is genuinely necessary in certain circumstances, general acceptance of the Razor places the burden of proof firmly on the side of those who would defend a more complex view of the world.

Theologically, Ockham agreed with Scotus that god is universal and has all of the infinite attributes. But he emphasized even more strongly that god’s freedom is absolutely unlimited. According to Ockham’s conception of voluntarism, god can will anything at all, even an outright logical contradiction, even though we cannot conceive of the possibility in specific terms. Thus, the regularity of nature is guaranteed only by divine benevolence, not by any logical or causal necessity.

Genuine human knowledge is always intuitive and incorrigible for Ockham, but its scope and extent are severely restricted by the limitations of our finite understandings. Were we to depend solely upon such perfect awareness of the external world, skepticism would be our only recourse. In the practical conduct of life, however, Ockham supposed that mere belief, based on sensory information and therefore prone to error, is nevertheless adequate for our usual needs. This notion of the importance but limitations of empirical knowledge would become a significant feature of British philosophy for many centuries.

The Collapse of Scholasticism

During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the critical spirit fostered by Scotus and Ockham began to undermine confidence in the scholastic project of synthesizing the philosophical and religious traditions in a comprehensive system of thought. John of Mirecourt, for example, used the problem of devising an adequate account of causation to argue that knowledge of the natural world is severely limited, and Jean Buridan abandoned theological pretension in order to focus narrowly on logical analysis of arguments.

Nicholas of Autrecourt argued that efforts to apply philosophical reasoning to Christian doctrine had failed and should be abandoned. Hasdai Crescas among the Jews and Meister Eckhart among the Christians employed rational methods only in order to generate paradoxical results that would demonstrate the need to rely upon mystical union with god as the foundation for genuine human knowledge.

The most remarkable of these late scholastic figures was Nicolas of Cusa, who made one final attempt at drawing together all of the inconsistent strands of medieval philosophy by deliberately embracing contradiction. Just as god’s perfect unity can encompass otherwise contradictory attributes, Cusa argued, so the contradictions apparent in the philosophical tradition should simply be embraced in a single comprehensive whole, without any undue concern for its logical consistency.

Meister Eckehart

The trend away from Aristotelianism was accentuated by the German Dominican Meister Eckehart (c. 1260–c. 1327), who developed a speculative mysticism of both Christian and Neoplatonic inspiration. Eckehart depicted the ascent of the soul to God in Neoplatonic terms: by gradually purifying itself from the body, the soul transcends being and knowledge until it is absorbed in the One. The soul is then united with God at its highest point, or “citadel.” God himself transcends being and knowledge. Sometimes Eckehart describes God as the being of all things. This language, which was also used by Erigena and other Christian Neoplatonists, leaves him open to the charge of pantheism (the doctrine that the being of creatures is identical with that of God); but for Eckehart there is an infinite gulf between creatures and God. Eckehart meant that creatures have no existence of their own but are given existence by God, as the body is made to exist and is contained by the soul. Eckehart’s profound influence can be seen in the flowering of mysticism in the German Rhineland in the late Middle Ages.

Nicholas of Cusa

Nicholas of Cusa (1401–64) also preferred the Neoplatonists to the Aristotelians. To him the philosophy of Aristotle is an obstacle to the mind in its ascent to God because its primary rule is the principle of contradiction, which denies the compatibility of contradictories. But God is the “coincidence of opposites.” Because he is infinite, he embraces all things in perfect unity; he is at once the maximum and the minimum. Nicholas uses mathematical symbols to illustrate how, in infinity, contradictories coincide. If a circle is enlarged, the curve of its circumference becomes less; if a circle is infinite, its circumference is a straight line. As for human knowledge of the infinite God, one must be content with conjecture or approximation to the truth. The absolute truth escapes human beings; their proper attitude is “learned ignorance.”

For Nicholas, God alone is absolutely infinite. The universe reflects this divine perfection and is relatively infinite. It has no circumference, for it is limited by nothing outside of itself. Neither has it a centre; the Earth is neither at the centre of the universe nor is it completely at rest. Place and motion are not absolute but relative to the observer. This new, non-Aristotelian conception of the universe anticipated some of the features of modern theories.

Thus, at the end of the Middle Ages, some of the most creative minds were abandoning Aristotelianism and turning to newer ways of thought. The philosophy of Aristotle, in its various interpretations, continued to be taught in the universities, but it had lost its vitality and creativity. Christian philosophers were once again finding inspiration in Neoplatonism. The Platonism of the Renaissance was directly continuous with the Platonism of the Middle Ages.

Candela Citations

- Final Scholastic Developments. Authored by: Garth Kemerling. Provided by: The Philosophy Pages. Located at: http://www.philosophypages.com/hy/3q.htm. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- William of Ockham, from stained glass window at a church in Surrey. Authored by: Moscarlop. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_of_Ockham#/media/File:William_of_Ockham.png. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Western Philosophy. Authored by: Armand Maurer. Provided by: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.. Located at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Western-philosophy. License: All Rights Reserved

- JohnDunsScotus - full. Authored by: Justus van Gent. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duns_Scotus#/media/File:JohnDunsScotus_-_full.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright