Learning Objectives

- Recognize the basic limit laws.

- Use the limit laws to evaluate the limit of a function.

- Evaluate the limit of a function by factoring.

- Use the limit laws to evaluate the limit of a polynomial or rational function.

- Evaluate the limit of a function by factoring or by using conjugates.

- Evaluate the limit of a function by using the squeeze theorem.

In the previous section, we evaluated limits by looking at graphs or by constructing a table of values. In this section, we establish laws for calculating limits and learn how to apply these laws. In the Student Project at the end of this section, you have the opportunity to apply these limit laws to derive the formula for the area of a circle by adapting a method devised by the Greek mathematician Archimedes. We begin by restating two useful limit results from the previous section. These two results, together with the limit laws, serve as a foundation for calculating many limits.

Evaluating Limits with the Limit Laws

The first two limit laws were stated in (Figure) and we repeat them here. These basic results, together with the other limit laws, allow us to evaluate limits of many algebraic functions.

Basic Limit Results

For any real number [latex]a[/latex] and any constant [latex]c[/latex],

-

[latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}x=a[/latex]

-

[latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}c=c[/latex]

Evaluating a Basic Limit

Evaluate each of the following limits using (Figure).

- [latex]\underset{x\to 2}{\lim}x[/latex]

- [latex]\underset{x\to 2}{\lim}5[/latex]

We now take a look at the limit laws, the individual properties of limits. The proofs that these laws hold are omitted here.

Limit Laws

Let [latex]f(x)[/latex] and [latex]g(x)[/latex] be defined for all [latex]x\ne a[/latex] over some open interval containing [latex]a[/latex]. Assume that [latex]L[/latex] and [latex]M[/latex] are real numbers such that [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)=L[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}g(x)=M[/latex]. Let [latex]c[/latex] be a constant. Then, each of the following statements holds:

Sum law for limits: [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}(f(x)+g(x))=\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)+\underset{x\to a}{\lim}g(x)=L+M[/latex]

Difference law for limits: [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}(f(x)-g(x))=\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)-\underset{x\to a}{\lim}g(x)=L-M[/latex]

Constant multiple law for limits: [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}cf(x)=c \cdot \underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)=cL[/latex]

Product law for limits: [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}(f(x) \cdot g(x))=\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x) \cdot \underset{x\to a}{\lim}g(x)=L \cdot M[/latex]

Quotient law for limits: [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}=\frac{\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)}{\underset{x\to a}{\lim}g(x)}=\frac{L}{M}[/latex] for [latex]M\ne 0[/latex]

Power law for limits: [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}(f(x))^n=(\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x))^n=L^n[/latex] for every positive integer [latex]n[/latex].

Root law for limits: [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}\sqrt[n]{f(x)}=\sqrt[n]{\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)}=\sqrt[n]{L}[/latex] for all [latex]L[/latex] if [latex]n[/latex] is odd and for [latex]L\ge 0[/latex] if [latex]n[/latex] is even.

We now practice applying these limit laws to evaluate a limit.

Evaluating a Limit Using Limit Laws

Use the limit laws to evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to -3}{\text{lim}}(4x+2).[/latex]

Using Limit Laws Repeatedly

Use the limit laws to evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to 2}{\text{lim}}\frac{2{x}^{2}-3x+1}{{x}^{3}+4}.[/latex]

Use the limit laws to evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to 6}{\text{lim}}(2x-1)\sqrt{x+4}.[/latex] In each step, indicate the limit law applied.

Limits of Polynomial and Rational Functions

By now you have probably noticed that, in each of the previous examples, it has been the case that [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}f(x)=f(a).[/latex] This is not always true, but it does hold for all polynomials for any choice of [latex]a[/latex] and for all rational functions at all values of [latex]a[/latex] for which the rational function is defined.

Limits of Polynomial and Rational Functions

Let [latex]p(x)[/latex] and [latex]q(x)[/latex] be polynomial functions. Let [latex]a[/latex] be a real number. Then,

To see that this theorem holds, consider the polynomial [latex]p(x)={c}_{n}{x}^{n}+{c}_{n-1}{x}^{n-1}+\cdots +{c}_{1}x+{c}_{0}.[/latex] By applying the sum, constant multiple, and power laws, we end up with

It now follows from the quotient law that if [latex]p(x)[/latex] and [latex]q(x)[/latex] are polynomials for which [latex]q(a)\ne 0,[/latex] then

(Figure) applies this result.

Evaluating a Limit of a Rational Function

Evaluate the [latex]\underset{x\to 3}{\text{lim}}\frac{2{x}^{2}-3x+1}{5x+4}.[/latex]

Evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to -2}{\text{lim}}(3{x}^{3}-2x+7).[/latex]

Hint

Use (Figure)

Additional Limit Evaluation Techniques

As we have seen, we may evaluate easily the limits of polynomials and limits of some (but not all) rational functions by direct substitution. However, as we saw in the introductory section on limits, it is certainly possible for [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}f(x)[/latex] to exist when [latex]f(a)[/latex] is undefined. The following observation allows us to evaluate many limits of this type:

If for all [latex]x\ne a,f(x)=g(x)[/latex] over some open interval containing [latex]a[/latex], then [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}f(x)=\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}g(x).[/latex]

To understand this idea better, consider the limit [latex]\underset{x\to 1}{\text{lim}}\frac{{x}^{2}-1}{x-1}.[/latex]

The function

and the function [latex]g(x)=x+1[/latex] are identical for all values of [latex]x\ne 1.[/latex] The graphs of these two functions are shown in (Figure).

Figure 1. The graphs of [latex]f(x)[/latex] and [latex]g(x)[/latex] are identical for all [latex]x\ne 1.[/latex] Their limits at 1 are equal.

We see that

The limit has the form [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}\frac{f(x)}{g(x)},[/latex] where [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}f(x)=0[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}g(x)=0.[/latex] (In this case, we say that [latex]f(x)\text{/}g(x)[/latex] has the indeterminate form [latex]0\text{/}0\text{.)}[/latex] The following Problem-Solving Strategy provides a general outline for evaluating limits of this type.

Problem-Solving Strategy: Calculating a Limit When [latex]f(x)\text{/}g(x)[/latex] has the Indeterminate Form 0/0

- First, we need to make sure that our function has the appropriate form and cannot be evaluated immediately using the limit laws.

- We then need to find a function that is equal to [latex]h(x)=f(x)\text{/}g(x)[/latex] for all [latex]x\ne a[/latex] over some interval containing [latex]a[/latex]. To do this, we may need to try one or more of the following steps:

- If [latex]f(x)[/latex] and [latex]g(x)[/latex] are polynomials, we should factor each function and cancel out any common factors.

- If the numerator or denominator contains a difference involving a square root, we should try multiplying the numerator and denominator by the conjugate of the expression involving the square root.

- If [latex]f(x)\text{/}g(x)[/latex] is a complex fraction, we begin by simplifying it.

- Last, we apply the limit laws.

The next examples demonstrate the use of this Problem-Solving Strategy. (Figure) illustrates the factor-and-cancel technique; (Figure) shows multiplying by a conjugate. In (Figure), we look at simplifying a complex fraction.

Evaluating a Limit by Factoring and Canceling

Evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to 3}{\text{lim}}\frac{{x}^{2}-3x}{2{x}^{2}-5x-3}.[/latex]

Evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to -3}{\text{lim}}\frac{{x}^{2}+4x+3}{{x}^{2}-9}.[/latex]

Hint

Follow the steps in the Problem-Solving Strategy and (Figure).

Evaluating a Limit by Multiplying by a Conjugate

Evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to -1}{\text{lim}}\frac{\sqrt{x+2}-1}{x+1}.[/latex]

Evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to 5}{\text{lim}}\frac{\sqrt{x-1}-2}{x-5}.[/latex]

Hint

Follow the steps in the Problem-Solving Strategy and (Figure).

Evaluating a Limit by Simplifying a Complex Fraction

Evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to 1}{\text{lim}}\frac{\frac{1}{x+1}-\frac{1}{2}}{x-1}.[/latex]

Evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to -3}{\text{lim}}\frac{\frac{1}{x+2}+1}{x+3}.[/latex]

Hint

Follow the steps in the Problem-Solving Strategy and (Figure).

(Figure) does not fall neatly into any of the patterns established in the previous examples. However, with a little creativity, we can still use these same techniques.

Evaluating a Limit When the Limit Laws Do Not Apply

Evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to 0}{\text{lim}}(\frac{1}{x}+\frac{5}{x(x-5)}).[/latex]

Evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to 3}{\text{lim}}(\frac{1}{x-3}-\frac{4}{{x}^{2}-2x-3}).[/latex]

Hint

Use the same technique as (Figure). Don’t forget to factor [latex]{x}^{2}-2x-3[/latex] before getting a common denominator.

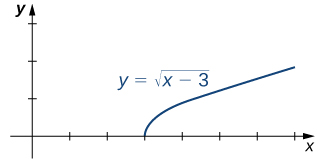

Let’s now revisit one-sided limits. Simple modifications in the limit laws allow us to apply them to one-sided limits. For example, to apply the limit laws to a limit of the form [latex]\underset{x\to {a}^{-}}{\text{lim}}h(x),[/latex] we require the function [latex]h(x)[/latex] to be defined over an open interval of the form [latex](b,a);[/latex] for a limit of the form [latex]\underset{x\to {a}^{+}}{\text{lim}}h(x),[/latex] we require the function [latex]h(x)[/latex] to be defined over an open interval of the form [latex](a,c).[/latex] (Figure) illustrates this point.

Evaluating a One-Sided Limit Using the Limit Laws

Evaluate each of the following limits, if possible.

- [latex]\underset{x\to {3}^{-}}{\text{lim}}\sqrt{x-3}[/latex]

- [latex]\underset{x\to {3}^{+}}{\text{lim}}\sqrt{x-3}[/latex]

In (Figure) we look at one-sided limits of a piecewise-defined function and use these limits to draw a conclusion about a two-sided limit of the same function.

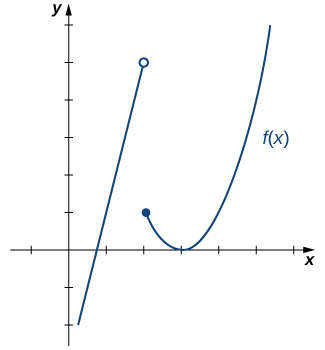

Evaluating a Two-Sided Limit Using the Limit Laws

For [latex]f(x)=\bigg\{\begin{array}{cc}4x-3\hfill & \text{ if }x<2\hfill \\ {(x-3)}^{2}\hfill & \text{ if }x\ge 2\hfill \end{array},[/latex] evaluate each of the following limits:

- [latex]\underset{x\to {2}^{-}}{\text{lim}}f(x)[/latex]

- [latex]\underset{x\to {2}^{+}}{\text{lim}}f(x)[/latex]

- [latex]\underset{x\to 2}{\text{lim}}f(x)[/latex]

Graph [latex]f(x)=\bigg\{\begin{array}{c}-x-2\text{ if }x<\text{−}1\\ 2\text{ if }x=-1\\ {x}^{3}\text{ if }x>\text{−}1\end{array}[/latex] and evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to {-1}^{-}}{\text{lim}}f(x).[/latex]

Hint

Use the method in (Figure) to evaluate the limit.

We now turn our attention to evaluating a limit of the form [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}\frac{f(x)}{g(x)},[/latex] where [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}f(x)=K,[/latex] where [latex]K\ne 0[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}g(x)=0.[/latex] That is, [latex]f(x)\text{/}g(x)[/latex] has the form [latex]K\text{/}0,K\ne 0[/latex] at [latex]a[/latex].

Evaluating a Limit of the Form [latex]K\text{/}0,K\ne 0[/latex] Using the Limit Laws

Evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to {2}^{-}}{\text{lim}}\frac{x-3}{{x}^{2}-2x}.[/latex]

Evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to 1}{\text{lim}}\frac{x+2}{{(x-1)}^{2}}.[/latex]

Hint

Use the methods from (Figure).

The Squeeze Theorem

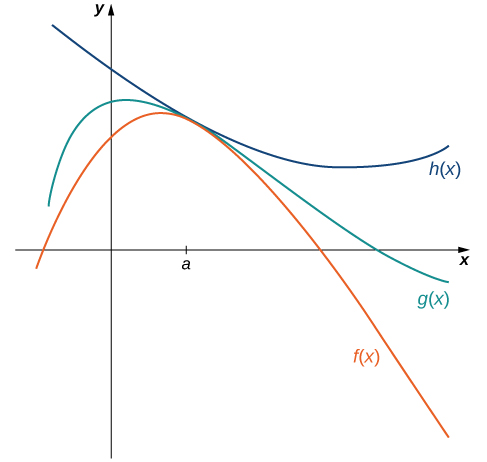

The techniques we have developed thus far work very well for algebraic functions, but we are still unable to evaluate limits of very basic trigonometric functions. The next theorem, called the squeeze theorem, proves very useful for establishing basic trigonometric limits. This theorem allows us to calculate limits by “squeezing” a function, with a limit at a point [latex]a[/latex] that is unknown, between two functions having a common known limit at [latex]a[/latex]. (Figure) illustrates this idea.

Figure 4. The Squeeze Theorem applies when [latex]f(x)\le g(x)\le h(x)[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}f(x)=\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}h(x).[/latex]

The Squeeze Theorem

Let [latex]f(x),g(x),[/latex] and [latex]h(x)[/latex] be defined for all [latex]x\ne a[/latex] over an open interval containing [latex]a[/latex]. If

for all [latex]x\ne a[/latex] in an open interval containing [latex]a[/latex] and

where L is a real number, then [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}g(x)=L.[/latex]

Applying the Squeeze Theorem

Apply the squeeze theorem to evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to 0}{\text{lim}}x \cos x.[/latex]

[/caption]

Use the squeeze theorem to evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to 0}{\text{lim}}{x}^{2} \sin \frac{1}{x}.[/latex]

Hint

Use the fact that [latex]-{x}^{2}\le {x}^{2} \sin (1\text{/}x)\le {x}^{2}[/latex] to help you find two functions such that [latex]{x}^{2} \sin (1\text{/}x)[/latex] is squeezed between them.

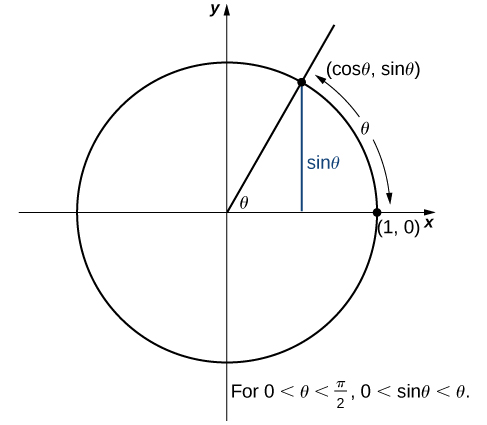

We now use the squeeze theorem to tackle several very important limits. Although this discussion is somewhat lengthy, these limits prove invaluable for the development of the material in both the next section and the next chapter. The first of these limits is [latex]\underset{\theta \to 0}{\text{lim}} \sin \theta .[/latex] Consider the unit circle shown in (Figure). In the figure, we see that [latex]\sin \theta[/latex] is the [latex]y[/latex]-coordinate on the unit circle and it corresponds to the line segment shown in blue. The radian measure of angle θ is the length of the arc it subtends on the unit circle. Therefore, we see that for [latex]0<\theta <\frac{\pi }{2},0< \sin \theta <\theta .[/latex]

Figure 6. The sine function is shown as a line on the unit circle.

Because [latex]\underset{\theta \to {0}^{+}}{\text{lim}}0=0[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to {0}^{+}}{\text{lim}}\theta =0,[/latex] by using the squeeze theorem we conclude that

To see that [latex]\underset{\theta \to {0}^{-}}{\text{lim}} \sin \theta =0[/latex] as well, observe that for [latex]-\frac{\pi }{2}<\theta <0,0<\text{−}\theta <\frac{\pi }{2}[/latex] and hence, [latex]0< \sin (-\theta )<\text{−}\theta .[/latex] Consequently, [latex]0<- \sin \theta <\text{−}\theta .[/latex] It follows that [latex]0> \sin \theta >\theta .[/latex] An application of the squeeze theorem produces the desired limit. Thus, since [latex]\underset{\theta \to {0}^{+}}{\text{lim}} \sin \theta =0[/latex] and [latex]\underset{\theta \to {0}^{-}}{\text{lim}} \sin \theta =0,[/latex]

Next, using the identity [latex]\cos \theta =\sqrt{1-{ \sin }^{2}\theta }[/latex] for [latex]-\frac{\pi }{2}<\theta <\frac{\pi }{2},[/latex] we see that

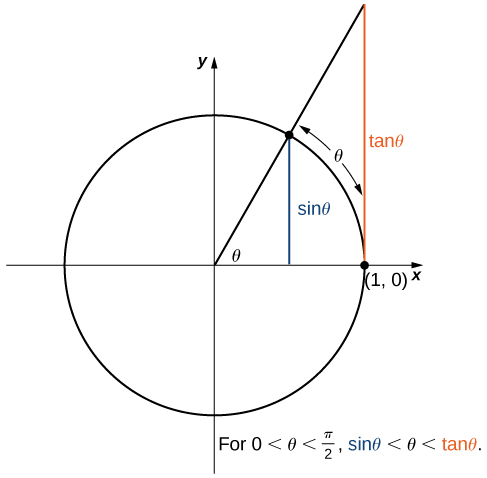

We now take a look at a limit that plays an important role in later chapters—namely, [latex]\underset{\theta \to 0}{\text{lim}}\frac{ \sin \theta }{\theta }.[/latex] To evaluate this limit, we use the unit circle in (Figure). Notice that this figure adds one additional triangle to (Figure). We see that the length of the side opposite angle θ in this new triangle is [latex]\tan \theta .[/latex] Thus, we see that for [latex]0<\theta <\frac{\pi }{2}, \sin \theta <\theta < \tan \theta .[/latex]

Figure 7. The sine and tangent functions are shown as lines on the unit circle.

By dividing by [latex]\sin \theta[/latex] in all parts of the inequality, we obtain

Equivalently, we have

Since [latex]\underset{\theta \to {0}^{+}}{\text{lim}}1=1=\underset{\theta \to {0}^{+}}{\text{lim}} \cos \theta ,[/latex] we conclude that [latex]\underset{\theta \to {0}^{+}}{\text{lim}}\frac{ \sin \theta }{\theta }=1.[/latex] By applying a manipulation similar to that used in demonstrating that [latex]\underset{\theta \to {0}^{-}}{\text{lim}} \sin \theta =0,[/latex] we can show that [latex]\underset{\theta \to {0}^{-}}{\text{lim}}\frac{ \sin \theta }{\theta }=1.[/latex] Thus,

In (Figure) we use this limit to establish [latex]\underset{\theta \to 0}{\text{lim}}\frac{1- \cos \theta }{\theta }=0.[/latex] This limit also proves useful in later chapters.

Evaluating an Important Trigonometric Limit

Evaluate [latex]\underset{\theta \to 0}{\text{lim}}\frac{1- \cos \theta }{\theta }.[/latex]

Evaluate [latex]\underset{\theta \to 0}{\text{lim}}\frac{1- \cos \theta }{ \sin \theta }.[/latex]

Hint

Multiply numerator and denominator by [latex]1+ \cos \theta .[/latex]

Deriving the Formula for the Area of a Circle

Some of the geometric formulas we take for granted today were first derived by methods that anticipate some of the methods of calculus. The Greek mathematician Archimedes (ca. 287−212; BCE) was particularly inventive, using polygons inscribed within circles to approximate the area of the circle as the number of sides of the polygon increased. He never came up with the idea of a limit, but we can use this idea to see what his geometric constructions could have predicted about the limit.

We can estimate the area of a circle by computing the area of an inscribed regular polygon. Think of the regular polygon as being made up of [latex]n[/latex] triangles. By taking the limit as the vertex angle of these triangles goes to zero, you can obtain the area of the circle. To see this, carry out the following steps:

- Express the height [latex]h[/latex] and the base [latex]b[/latex] of the isosceles triangle in (Figure) in terms of [latex]\theta[/latex] and [latex]r[/latex].

Figure 8.

- Using the expressions that you obtained in step 1, express the area of the isosceles triangle in terms of θ and [latex]r[/latex].

(Substitute [latex](1\text{/}2) \sin \theta[/latex] for [latex]\sin (\theta \text{/}2) \cos (\theta \text{/}2)[/latex] in your expression.) - If an [latex]n[/latex]-sided regular polygon is inscribed in a circle of radius [latex]r[/latex], find a relationship between θ and [latex]n[/latex]. Solve this for [latex]n[/latex]. Keep in mind there are 2π radians in a circle. (Use radians, not degrees.)

- Find an expression for the area of the [latex]n[/latex]-sided polygon in terms of [latex]r[/latex] and θ.

- To find a formula for the area of the circle, find the limit of the expression in step 4 as θ goes to zero. (Hint: [latex]\underset{\theta \to 0}{\text{lim}}\frac{( \sin \theta )}{\theta }=1\text{).}[/latex]

The technique of estimating areas of regions by using polygons is revisited in Introduction to Integration.

Key Concepts

- The limit laws allow us to evaluate limits of functions without having to go through step-by-step processes each time.

- For polynomials and rational functions, [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}f(x)=f(a).[/latex]

- You can evaluate the limit of a function by factoring and canceling, by multiplying by a conjugate, or by simplifying a complex fraction.

- The squeeze theorem allows you to find the limit of a function if the function is always greater than one function and less than another function with limits that are known.

Key Equations

- Basic Limit Results

[latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}x=a\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}c=c[/latex] - Important Limits

[latex]\underset{\theta \to 0}{\text{lim}} \sin \theta =0[/latex]

[latex]\underset{\theta \to 0}{\text{lim}} \cos \theta =1[/latex]

[latex]\underset{\theta \to 0}{\text{lim}}\frac{ \sin \theta }{\theta }=1[/latex]

[latex]\underset{\theta \to 0}{\text{lim}}\frac{1- \cos \theta }{\theta }=0[/latex]

In the following exercises, use the limit laws to evaluate each limit. Justify each step by indicating the appropriate limit law(s).

[latex]\underset{x\to 0}{\text{lim}}(4{x}^{2}-2x+3)[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 1}{\text{lim}}\frac{{x}^{3}+3{x}^{2}+5}{4-7x}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to -2}{\text{lim}}\sqrt{{x}^{2}-6x+3}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to -1}{\text{lim}}{(9x+1)}^{2}[/latex]

In the following exercises, use direct substitution to evaluate each limit.

[latex]\underset{x\to 7}{\text{lim}}{x}^{2}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to -2}{\text{lim}}(4{x}^{2}-1)[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 0}{\text{lim}}\frac{1}{1+ \sin x}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 2}{\text{lim}}{e}^{2x-{x}^{2}}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 1}{\text{lim}}\frac{2-7x}{x+6}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 3}{\text{lim}}\text{ln}{e}^{3x}[/latex]

In the following exercises, use direct substitution to show that each limit leads to the indeterminate form [latex]0\text{/}0.[/latex] Then, evaluate the limit.

[latex]\underset{x\to 4}{\text{lim}}\frac{{x}^{2}-16}{x-4}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 2}{\text{lim}}\frac{x-2}{{x}^{2}-2x}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 6}{\text{lim}}\frac{3x-18}{2x-12}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{h\to 0}{\text{lim}}\frac{{(1+h)}^{2}-1}{h}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{t\to 9}{\text{lim}}\frac{t-9}{\sqrt{t}-3}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{h\to 0}{\text{lim}}\frac{\frac{1}{a+h}-\frac{1}{a}}{h},[/latex] where [latex]a[/latex] is a real-valued constant

[latex]\underset{\theta \to \pi }{\text{lim}}\frac{ \sin \theta }{ \tan \theta }[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 1}{\text{lim}}\frac{{x}^{3}-1}{{x}^{2}-1}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 1\text{/}2}{\text{lim}}\frac{2{x}^{2}+3x-2}{2x-1}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to -3}{\text{lim}}\frac{\sqrt{x+4}-1}{x+3}[/latex]

In the following exercises, use direct substitution to obtain an undefined expression. Then, use the method of (Figure) to simplify the function to help determine the limit.

[latex]\underset{x\to {-2}^{-}}{\text{lim}}\frac{2{x}^{2}+7x-4}{{x}^{2}+x-2}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to {-2}^{+}}{\text{lim}}\frac{2{x}^{2}+7x-4}{{x}^{2}+x-2}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to {1}^{-}}{\text{lim}}\frac{2{x}^{2}+7x-4}{{x}^{2}+x-2}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to {1}^{+}}{\text{lim}}\frac{2{x}^{2}+7x-4}{{x}^{2}+x-2}[/latex]

In the following exercises, assume that [latex]\underset{x\to 6}{\text{lim}}f(x)=4,\underset{x\to 6}{\text{lim}}g(x)=9,[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to 6}{\text{lim}}h(x)=6.[/latex] Use these three facts and the limit laws to evaluate each limit.

[latex]\underset{x\to 6}{\text{lim}}2f(x)g(x)[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 6}{\text{lim}}\frac{g(x)-1}{f(x)}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 6}{\text{lim}}(f(x)+\frac{1}{3}g(x))[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 6}{\text{lim}}\frac{{(h(x))}^{3}}{2}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 6}{\text{lim}}\sqrt{g(x)-f(x)}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 6}{\text{lim}}x·h(x)[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 6}{\text{lim}}\left[(x+1)·f(x)\right][/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 6}{\text{lim}}(f(x)·g(x)-h(x))[/latex]

[T] In the following exercises, use a calculator to draw the graph of each piecewise-defined function and study the graph to evaluate the given limits.

[latex]f(x)=\bigg\{\begin{array}{ll}{x}^{2},& x\le 3\hfill \\ x+4,& x>3\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

- [latex]\underset{x\to {3}^{-}}{\text{lim}}f(x)[/latex]

- [latex]\underset{x\to {3}^{+}}{\text{lim}}f(x)[/latex]

[latex]g(x)=\bigg\{\begin{array}{ll}{x}^{3}-1,& x\le 0\hfill \\ 1,& x>0\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

- [latex]\underset{x\to {0}^{-}}{\text{lim}}g(x)[/latex]

- [latex]\underset{x\to {0}^{+}}{\text{lim}}g(x)[/latex]

[latex]h(x)=\bigg\{\begin{array}{ll}{x}^{2}-2x+1,& x<2\hfill \\ 3-x,& x\ge 2\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

- [latex]\underset{x\to {2}^{-}}{\text{lim}}h(x)[/latex]

- [latex]\underset{x\to {2}^{+}}{\text{lim}}h(x)[/latex]

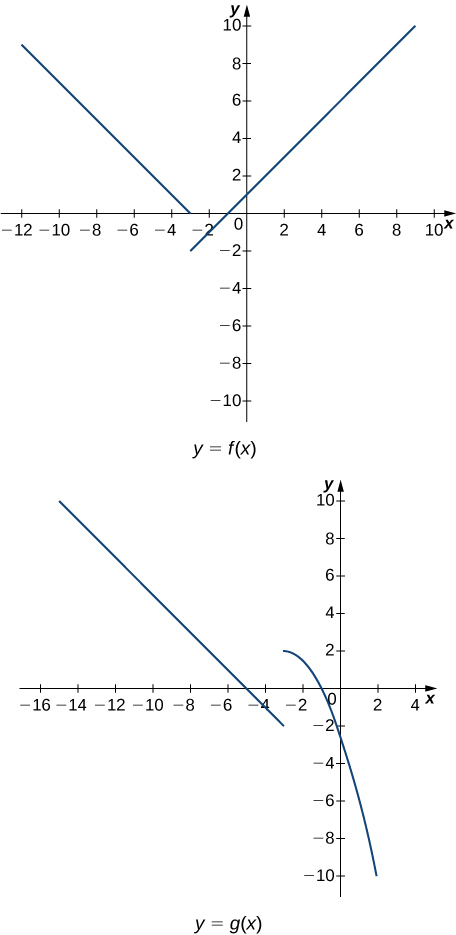

In the following exercises, use the following graphs and the limit laws to evaluate each limit.

[latex]\underset{x\to {-3}^{+}}{\text{lim}}(f(x)+g(x))[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to {-3}^{-}}{\text{lim}}(f(x)-3g(x))[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 0}{\text{lim}}\frac{f(x)g(x)}{3}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to -5}{\text{lim}}\frac{2+g(x)}{f(x)}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 1}{\text{lim}}{(f(x))}^{2}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 1}{\text{lim}}\sqrt{f(x)-g(x)}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 1}{\text{lim}}\sqrt[3]{f(x)-g(x)}=\sqrt[3]{\underset{x\to 1}{\text{lim}}f(x)-\underset{x\to 1}{\text{lim}}g(x)}=\sqrt[3]{2+5}=\sqrt[3]{7}[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to -7}{\text{lim}}(x·g(x))[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to -9}{\text{lim}}\left[x·f(x)+2·g(x)\right][/latex]

For the following problems, evaluate the limit using the squeeze theorem. Use a calculator to graph the functions [latex]f(x),g(x),[/latex] and [latex]h(x)[/latex] when possible.

[T] True or False? If [latex]2x-1\le g(x)\le {x}^{2}-2x+3,[/latex] then [latex]\underset{x\to 2}{\text{lim}}g(x)=0.[/latex]

[T][latex]\underset{\theta \to 0}{\text{lim}}{\theta }^{2} \cos (\frac{1}{\theta })[/latex]

[latex]\underset{x\to 0}{\text{lim}}f(x),[/latex] where [latex]f(x)=\bigg\{\begin{array}{ll}0,& x\text{rational}\hfill \\ {x}^{2},& x\text{irrrational}\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

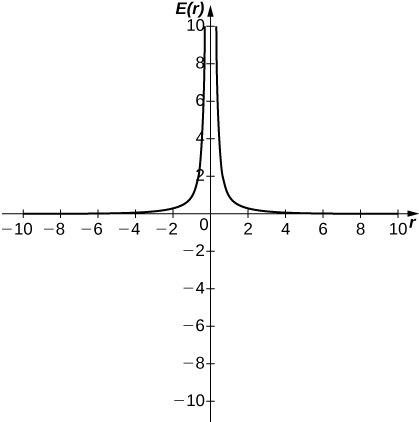

[T] In physics, the magnitude of an electric field generated by a point charge at a distance [latex]r[/latex] in vacuum is governed by Coulomb’s law: [latex]E(r)=\frac{q}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}{r}^{2}},[/latex] where E represents the magnitude of the electric field, [latex]q[/latex] is the charge of the particle, [latex]r[/latex] is the distance between the particle and where the strength of the field is measured, and [latex]\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}[/latex] is Coulomb’s constant: [latex]8.988×{10}^{9}\text{N}·{\text{m}}^{2}\text{/}{\text{C}}^{2}.[/latex]

- Use a graphing calculator to graph [latex]E(r)[/latex] given that the charge of the particle is [latex]q={10}^{-10}.[/latex]

- Evaluate [latex]\underset{r\to {0}^{+}}{\text{lim}}E(r).[/latex] What is the physical meaning of this quantity? Is it physically relevant? Why are you evaluating from the right?

[T] The density of an object is given by its mass divided by its volume: [latex]\rho =m\text{/}V.[/latex]

- Use a calculator to plot the volume as a function of density [latex](V=m\text{/}\rho ),[/latex] assuming you are examining something of mass 8 kg ([latex]m=8\text{).}[/latex]

- Evaluate [latex]\underset{\rho \to {0}^{+}}{\text{lim}}V(\rho )[/latex] and explain the physical meaning.

Glossary

- constant multiple law for limits

- the limit law [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}cf(x)=c·\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}f(x)=cL[/latex]

- difference law for limits

- the limit law [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}(f(x)-g(x))=\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}f(x)-\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}g(x)=L-M[/latex]

- limit laws

- the individual properties of limits; for each of the individual laws, let [latex]f(x)[/latex] and [latex]g(x)[/latex] be defined for all [latex]x\ne a[/latex] over some open interval containing [latex]a[/latex]; assume that L and M are real numbers so that [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}f(x)=L[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}g(x)=M;[/latex] let [latex]c[/latex] be a constant

- power law for limits

- the limit law [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}{(f(x))}^{n}={(\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}f(x))}^{n}={L}^{n}[/latex] for every positive integer [latex]n[/latex]

- product law for limits

- the limit law [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}(f(x)·g(x))=\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}f(x)·\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}g(x)=L·M[/latex]

- quotient law for limits

- the limit law [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}=\frac{\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}f(x)}{\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}g(x)}=\frac{L}{M}[/latex] for [latex]M\ne 0[/latex]

- root law for limits

- the limit law [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}\sqrt[n]{f(x)}=\sqrt[n]{\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}f(x)}=\sqrt[n]{L}[/latex] for all L if [latex]n[/latex] is odd and for [latex]L\ge 0[/latex] if [latex]n[/latex] is even

- squeeze theorem

- states that if [latex]f(x)\le g(x)\le h(x)[/latex] for all [latex]x\ne a[/latex] over an open interval containing [latex]a[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}f(x)=L=\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}h(x)[/latex] where L is a real number, then [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}g(x)=L[/latex]

- sum law for limits

- The limit law [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}(f(x)+g(x))=\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}f(x)+\underset{x\to a}{\text{lim}}g(x)=L+M[/latex]

Figure 5. The graphs of [latex]f(x),g(x),[/latex] and [latex]h(x)[/latex] are shown around the point [latex]x=0.[/latex]

Figure 5. The graphs of [latex]f(x),g(x),[/latex] and [latex]h(x)[/latex] are shown around the point [latex]x=0.[/latex]

![The graph of three functions over the domain [-1,1], colored red, green, and blue as follows: red: theta^2, green: theta^2 * cos (1/theta), and blue: - (theta^2). The red and blue functions open upwards and downwards respectively as parabolas with vertices at the origin. The green function is trapped between the two.](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/courses-images/wp-content/uploads/sites/2332/2018/01/11203457/CNX_Calc_Figure_02_03_206.jpg)

Hint

Begin by applying the product law.