Equity Theory

In contrast to the need-based theories we have covered so far, process-based theories view motivation as a rational process. Individuals analyze their environment, develop reactions and feelings, and respond in certain predictable ways.

Equity theory attempts to explain relational satisfaction in terms of perceived fairness: that is, people evaluate the extent to which there is a fair or unfair distribution of resources within their interpersonal relationships. Regarded as one of many theories of justice, equity theory was first developed in 1963 by John Stacey Adams. Adams, a workplace and behavioral psychologist, asserted that employees seek to maintain equity between what they put into a job and what they receive from it against the perceived inputs and outcomes of others.

Equity theory proposes that people value fair treatment, which motivates them to maintain a similar standard of fairness with their coworkers and the organization. Accordingly, equity structure in the workplace is based on the ratio of inputs to outcomes.

Inputs are the employee’s contribution to the workplace. Inputs include time spent working and level of effort but can also include less tangible contributions such as loyalty, commitment, and enthusiasm.

Outputs are what the employee receives from the employer and can also be tangible or intangible. Tangible outcomes include salary and job security. Intangible outcomes might be recognition, praise, or a sense of achievement.

For example, let’s look at Ross and Monica, two employees who work for a large magazine-publishing company doing very similar jobs. If Ross received a raise in pay but saw that Monica was given a larger raise for the same amount of work, Ross would evaluate this change, perceive an inequality, and be distressed. However, if Ross perceived that Monica were being given more responsibility and therefore relatively more work along with the salary increase, then he would see no loss in equality status and not object to the change.

An employee will feel that he is treated fairly if he perceives the ratio of his inputs to his outcomes to be equivalent to those around him.

Equity theory includes the following primary propositions:

- Individuals will try to maximize their outcomes.

- Individuals can maximize collective rewards by evolving accepted systems for equitably apportioning resources among members. As a result, groups will evolve such systems of equity and will attempt to induce members to accept and adhere to these systems. In addition, groups will generally reward members who treat others equitably and punish members who treat others inequitably.

- When individuals find themselves participating in inequitable relationships, they will become distressed. The more inequitable the relationship, the more distress they will feel. According to equity theory, the person who gets “too much” and the person who gets “too little” both feel distressed. The person who gets too much may feel guilt or shame. The person who gets too little may feel angry or humiliated.

- Individuals who discover they are in inequitable relationships will attempt to eliminate their distress by restoring equity.

The focus of equity theory is on determining whether the distribution of resources is fair to both relational partners. Partners do not have to receive equal benefits (such as receiving the same amount of love, care, and financial security) or make equal contributions (such as investing the same amount of effort, time, and financial resources), as long as the ratio between these benefits and contributions is similar.

In other words, Ross perceives equity if Monica makes more money but also has more job responsibilities, because the ratio of inputs (job responsibilities) to outcomes (salary) is about the same. On the other hand, Ross would perceive inequity if the ratio were different—say if Monica made more money for the same job or if Monica made a salary equal to Ross’s but had fewer job responsibilities.

When an employee is comparing his input/outcome ratio to his fellow workers’, he will look for other employees with similar jobs or skill sets. For example, Ross would not compare his salary and responsibilities to those of the magazine company’s CEO. However, he might look outside the organization for comparison—for instance, he might visit glassdoor.com to check salaries for positions like his at other publishing houses.

Much like other prevalent theories of motivation, such as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, equity theory acknowledges that subtle and variable factors affect people’s assessment and perception of their standing relative to others. According to Adams, underpayment inequity induces anger, while overpayment induces guilt. Compensation, whether hourly or salaried, is a central concern for employees and is therefore the cause of equity or inequity in most, but not all, cases.

In any position, employees want to feel that their contributions and work performance are being rewarded with fair pay. An employee who feels underpaid may experience feelings of hostility toward the organization and perhaps coworkers. This hostility may cause the employee to underperform and breed job dissatisfaction among others.

Subtle or intangible compensation also plays an important role in feelings about equity. Receiving recognition and being thanked for strong job performance can help employees feel valued and satisfied with their jobs, resulting in better outcomes for both the individual and the organization.

Equity theory has several implications for business managers, as follow:

- Employees measure the totals of their inputs and outcomes. This means a working parent may accept lower monetary compensation in return for more flexible working hours.

- Different employees ascribe different personal values to inputs and outcomes. Thus, two employees of equal experience and qualification performing the same work for the same pay may have quite different perceptions of the fairness of the deal.

- Employees are able to adjust for purchasing power and local market conditions. Thus a teacher from Vancouver, Washington, may accept lower compensation than his colleague in Seattle if his cost of living is different, while a teacher in a remote African village may accept a totally different pay structure.

- Although it may be acceptable for more senior staff to receive higher compensation, there are limits to the balance of the scales of equity, and employees can find excessive executive pay demotivating.

- Staff perceptions of inputs and outcomes of themselves and others may be incorrect, and perceptions need to be managed effectively.

Expectancy Theory

Expectancy theory, initially put forward by Victor Vroom at the Yale School of Management, suggests that behavior is motivated by anticipated results or consequences. Vroom proposed that a person decides to behave in a certain way based on the expected result of the chosen behavior. For example, people will be willing to work harder if they think the extra effort will be rewarded.

In essence, individuals make choices based on estimates of how well the expected results of a given behavior are going to match up with or eventually lead to the desired results. This process begins in childhood and continues throughout a person’s life. Expectancy theory has three components: expectancy, instrumentality, and valence.

Expectancy is the individual’s belief that effort will lead to the intended performance goals. Expectancy describes the person’s belief that “I can do this.” Usually, this belief is based on an individual’s past experience, self-confidence, and the perceived difficulty of the performance standard or goal. Factors associated with the individual’s expectancy perception are competence, goal difficulty, and control.

Instrumentality is the belief that a person will receive a desired outcome if the performance expectation is met. Instrumentality reflects the person’s belief that, “If I accomplish this, I will get that.” The desired outcome may come in the form of a pay increase, promotion, recognition, or sense of accomplishment. Having clear policies in place—preferably spelled out in a contract—guarantees that the reward will be delivered if the agreed-upon performance is met. Instrumentality is low when the outcome is vague or uncertain, or if the outcome is the same for all possible levels of performance.

Valence is the unique value an individual places on a particular outcome. Valence captures the fact that “I find this particular outcome desirable because I’m me.” Factors associated with the individual’s valence are needs, goals, preferences, values, sources of motivation, and the strength of an individual’s preference for a particular outcome. An outcome that one employee finds motivating and desirable—such as a bonus or pay raise—may not be motivating and desirable to another (who may, for example, prefer greater recognition or more flexible working hours).

Expectancy theory, when properly followed, can help managers understand how individuals are motivated to choose among various behavioral alternatives. To enhance the connection between performance and outcomes, managers should use systems that tie rewards very closely to performance. They can also use training to help employees improve their abilities and believe that added effort will, in fact, lead to better performance.

It’s important to understand that expectancy theory can run aground if managers interpret it too simplistically. Vroom’s theory entails more than just the assumption that people will work harder if they think the effort will be rewarded. The reward needs to be meaningful and take valence into account. Valence has a significant cultural as well as personal dimension, as illustrated by the following case: When Japanese motor company ASMO opened a plant in the U.S., it brought with it a large Japanese workforce but hired American managers to oversee operations. The managers, thinking to motivate their workers with a reward system, initiated a costly employee-of-the-month program that included free parking and other perks. The program was a huge flop, and participation was disappointingly low. Why? The program required employees to nominate their coworkers to be considered for the award. Japanese culture values modesty, teamwork, and conformity, and to be put forward or singled out for being special is considered inappropriate and even shameful. To be named Employee of the Month would be a very great embarrassment indeed—not at all the reward that management assumed. Especially as companies become more culturally diverse, the lesson is that managers need to get to know their employees and their needs—their unique valences—if they want to understand what makes them feel motivated, happy, and valued.

Reinforcement Theory

Operant Conditioning

The basic premise of the theory of reinforcement is both simple and intuitive: An individual’s behavior is a function of the consequences of that behavior. You can think of it as simple cause and effect. If I work hard today, I’ll make more money. If I make more money, I’m more likely to want to work hard. Such a scenario creates behavioral reinforcement, where the desired behavior is enabled and promoted by the desired outcome of a behavior.

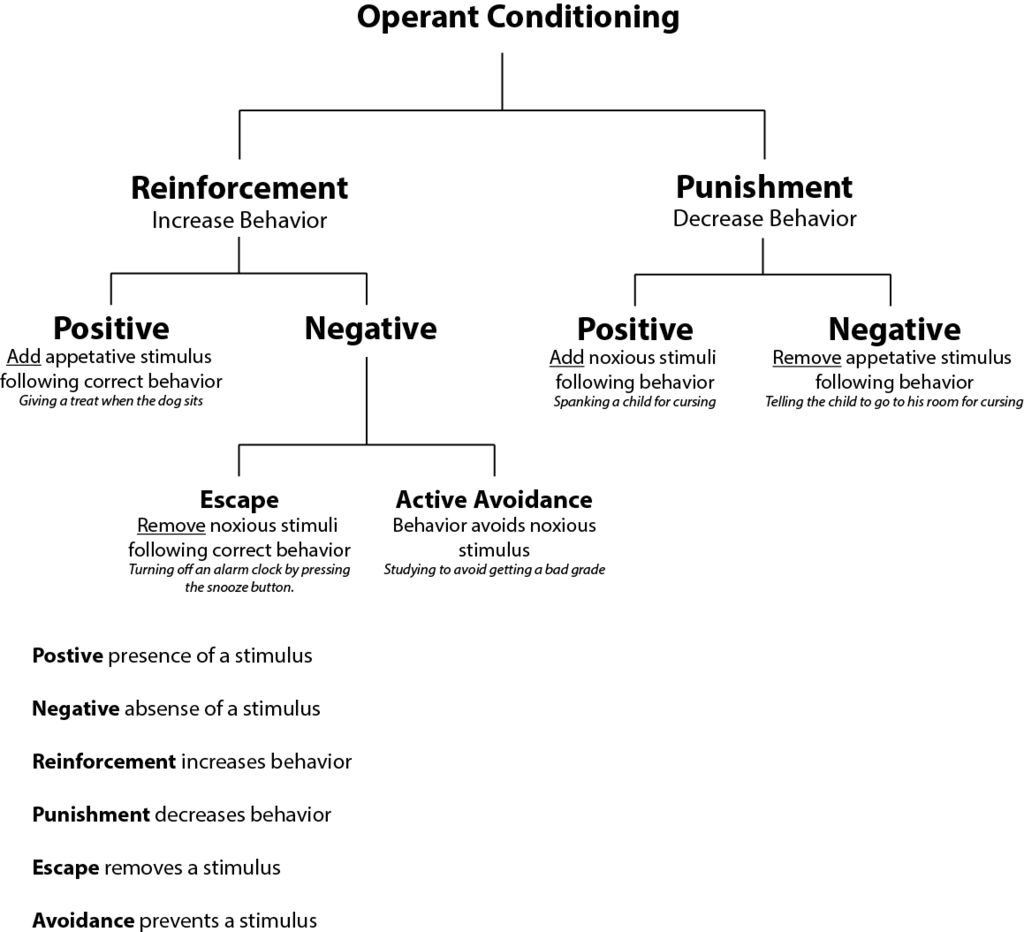

Reinforcement theory is based on work done by B. F. Skinner in the field of operant conditioning. The theory relies on four primary inputs, or aspects of operant conditioning, from the external environment. These four inputs are positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment.

Reinforcement

Positive reinforcement attempts to increase the frequency of a behavior by rewarding that behavior. For example, if an employee identifies a new market opportunity that creates profit, an organization may give her a bonus. This will positively reinforce the desired behavior.

Negative reinforcement, on the other hand, attempts to increase the frequency of a behavior by removing something the individual doesn’t like. For example, an employee demonstrates a strong work ethic and wraps up a few projects faster than expected. This employee happens to have a long commute. The manager tells the employee to go ahead and work from home for a few days, considering how much progress she has made. This is an example of removing a negative stimulus as way of reinforcing a behavior.

Reinforcement can be affected by various factors, including the following:

- Satiation: the degree of need. If an employee is quite wealthy, for example, it may not be particularly reinforcing (or motivating) to offer a bonus.

- Immediacy: the time elapsed between the desired behavior and the reinforcement. The shorter the time between the two, the more likely it is that the employee will correlate the reinforcement with the behavior. If an employee does something great but isn’t rewarded until two months after, he or she may not connect the desired behavior with the outcome. The reinforcement loses meaning and power.

- Size: the magnitude of a reward or punishment can have a big effect on the degree of response. For example, a bigger bonus often has a bigger impact (to an extent; see the satiation factor, above).

In a management context, reinforcers include salary increases, bonuses, promotions, variable incomes, flexible work hours, and paid sabbaticals.Managers are responsible for identifying the behaviors that should be promoted, the ones that should be discouraged, and carefully consider how those behaviors related to organizational objectives. Implementing rewards and punishments that are aligned with the organization’s goals helps to create a more consistent, efficient work culture.

One particularly common positive-reinforcement technique is the incentive program, a formal scheme used to promote or encourage specific actions, behaviors, or results from employees during a defined period of time. Incentive programs can reduce turnover, boost morale and loyalty, improve wellness, increase retention, and drive daily performance among employees. Motivating staff can, in turn, help businesses increase productivity and meet goals.

Let’s look at an IT sales team as an example: The team’s overarching goal is to sell their new software to businesses. The manager may want to emphasize sales to partners of a certain size (i.e., big contracts). To this end, the manager may reward team members who gain clients of 5,000 or more employees with a commission of 5 percent of the overall sales volume for each such partner. This reward reinforces the behavior of closing big contracts, strongly motivating team members to work toward that goal, and likely increases the total number of big contracts closed.

To maximize the impact of such a reinforcement, every feature of the incentive program must be tailored to the participants’ interests. A successful incentive program contains clearly defined rules, suitable rewards, efficient communication strategies, and measurable success metrics. By adapting each element of the program to fit the target audience, companies are better able to engage participating employees and enhance the overall program efficacy.

Punishment

Positive punishment is conditioning at its most straightforward: identifying a negative behavior and providing an adverse stimulus to discourage future occurrences. A simple example would be suspending an employee for inappropriate behavior.

Negative punishment entails the removal or withholding of something in order to condition a response. For example, an employee in the IT department prefers to work unconventional hours, from 10:30 a.m. to 7 p.m. However, her performance has been suffering lately. A negative punishment would be to revoke her right to keep the preferred schedule until performance improves.

The purpose of punishment is to prevent future occurrences of a particular socially unacceptable or undesirable behavior. According to deterrence theory, the awareness of a punishment can prevent people from engaging in the behavior. This can be accomplished either by punishing someone immediately after the undesirable behavior, so they are reluctant to do it again, or by educating people about the punishment preemptively, so they are inclined not to engage in the behavior at all. In a management context, punishment tools can include demotions, salary cuts, and terminations.

In business organizations, punishment and deterrence theory play a vital role in shaping the work culture to be in line with operational expectations and to avoid conflicts and negative outcomes both internally and externally. If employees know exactly what they are not supposed to do, and they understand the possible repercussions of violating those expectations, they will generally try to avoid crossing the line. Prevention is a much cheaper and easier approach than waiting for something bad to happen, so preemptive education regarding rules—and the penalties for violations—is common practice, especially in the area of business ethics.

For a humorous take on operant conditioning, take a look at the following videos from the show The Big Bang Theory:

https://youtu.be/Mt4N9GSBoMI

Check Your Understanding

Answer the question(s) below to see how well you understand the topics covered above. This short quiz does not count toward your grade in the class, and you can retake it an unlimited number of times.

Use this quiz to check your understanding and decide whether to (1) study the previous section further or (2) move on to the next section.

Candela Citations

- Revision and adaptation. Authored by: Linda Williams and Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Check Your Understanding. Authored by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Boundless Business. Provided by: Boundless. Located at: https://www.boundless.com/business/textbooks/boundless-business-textbook/motivation-theories-and-applications-11/modern-views-on-motivation-76/equity-theory-360-3209/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless Management. Provided by: Boundless. Located at: https://www.boundless.com/management/textbooks/boundless-management-textbook/organizational-behavior-5/process-and-motivation-47/equity-theory-240-3949/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Scales of Justice. Authored by: Michael Coghlan. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/mikecogh/8035396680/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless Management. Provided by: Boundless. Located at: https://www.boundless.com/management/textbooks/boundless-management-textbook/organizational-behavior-5/process-and-motivation-47/expectancy-theory-242-3951/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Expectation. Authored by: Yossi Gurvitz. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/ygurvitz/551720499/. License: CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- Boundless Business. Provided by: Boundless. Located at: https://www.boundless.com/business/textbooks/boundless-business-textbook/motivation-theories-and-applications-11/modern-views-on-motivation-76/reinforcement-theory-363-10337/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless Management. Provided by: Boundless. Located at: https://www.boundless.com/management/textbooks/boundless-management-textbook/organizational-behavior-5/reinforcement-and-motivation-48/reinforcement-as-a-management-tool-245-3538/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless Management. Provided by: Boundless. Located at: https://www.boundless.com/management/textbooks/boundless-management-textbook/organizational-behavior-5/reinforcement-and-motivation-48/punishment-as-a-management-tool-248-3541/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless Management. Provided by: Boundless. Located at: https://www.boundless.com/management/textbooks/boundless-management-textbook/organizational-behavior-5/reinforcement-and-motivation-48/managerial-perspectives-on-motivation-249-10517/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Dog Trick. Authored by: Keith Bacongco. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/kitoy/3239635945/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Big Bang Theory-operant conditioning. Authored by: TeachingBizVids. Located at: https://youtu.be/Mt4N9GSBoMI. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Operant Conditioning - Negative Reinforcement vs Positive Punishment. Authored by: Megan Deering. Located at: https://youtu.be/LhI5h5JZi-U. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license