Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe important physical features of wave forms

- Show how physical properties of light waves are associated with perceptual experience

- Show how physical properties of sound waves are associated with perceptual experience

Visual and auditory stimuli both occur in the form of waves. Although the two stimuli are very different in terms of composition, wave forms share similar characteristics that are especially important to our visual and auditory perceptions. In this section, we describe the physical properties of the waves as well as the perceptual experiences associated with them.

AMPLITUDE AND WAVELENGTH

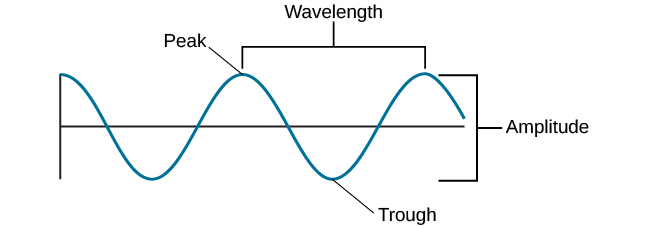

Two physical characteristics of a wave are amplitude and wavelength ([link]). The amplitude of a wave is the height of a wave as measured from the highest point on the wave (peak or crest) to the lowest point on the wave (trough). Wavelength refers to the length of a wave from one peak to the next.

The amplitude or height of a wave is measured from the peak to the trough. The wavelength is measured from peak to peak.

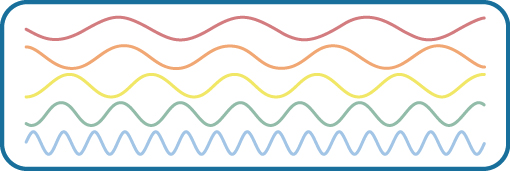

Wavelength is directly related to the frequency of a given wave form. Frequency refers to the number of waves that pass a given point in a given time period and is often expressed in terms of hertz (Hz), or cycles per second. Longer wavelengths will have lower frequencies, and shorter wavelengths will have higher frequencies ([link]).

This figure illustrates waves of differing wavelengths/frequencies. At the top of the figure, the red wave has a long wavelength/short frequency. Moving from top to bottom, the wavelengths decrease and frequencies increase.

LIGHT WAVES

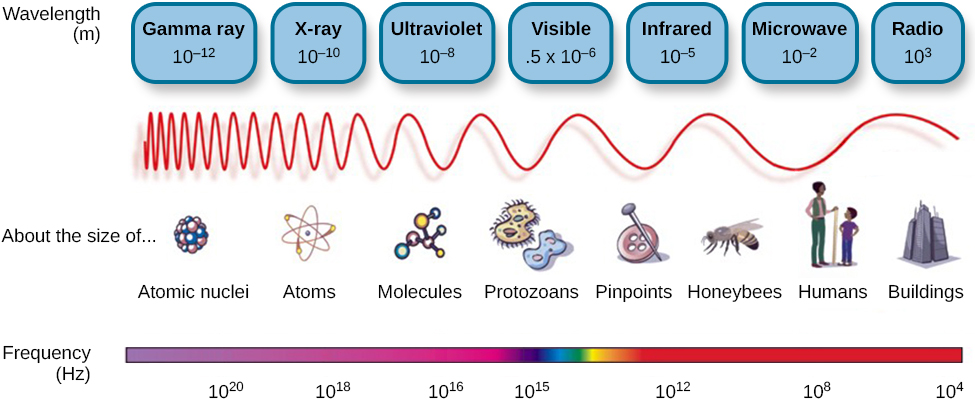

The visible spectrum is the portion of the larger electromagnetic spectrum that we can see. As [link] shows, the electromagnetic spectrum encompasses all of the electromagnetic radiation that occurs in our environment and includes gamma rays, x-rays, ultraviolet light, visible light, infrared light, microwaves, and radio waves. The visible spectrum in humans is associated with wavelengths that range from 380 to 740 nm—a very small distance, since a nanometer (nm) is one billionth of a meter. Other species can detect other portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. For instance, honeybees can see light in the ultraviolet range (Wakakuwa, Stavenga, & Arikawa, 2007), and some snakes can detect infrared radiation in addition to more traditional visual light cues (Chen, Deng, Brauth, Ding, & Tang, 2012; Hartline, Kass, & Loop, 1978).

Light that is visible to humans makes up only a small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum.

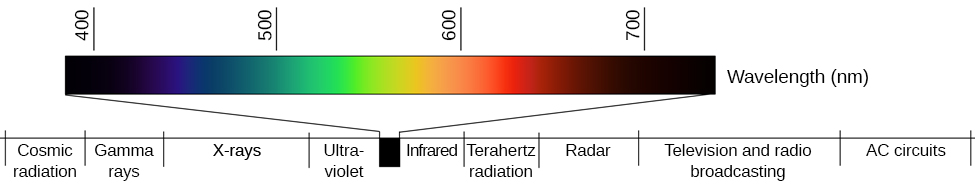

In humans, light wavelength is associated with perception of color ([link]). Within the visible spectrum, our experience of red is associated with longer wavelengths, greens are intermediate, and blues and violets are shorter in wavelength. (An easy way to remember this is the mnemonic ROYGBIV: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet.) The amplitude of light waves is associated with our experience of brightness or intensity of color, with larger amplitudes appearing brighter.

Different wavelengths of light are associated with our perception of different colors. (credit: modification of work by Johannes Ahlmann)

SOUND WAVES

Like light waves, the physical properties of sound waves are associated with various aspects of our perception of sound. The frequency of a sound wave is associated with our perception of that sound’s pitch. High-frequency sound waves are perceived as high-pitched sounds, while low-frequency sound waves are perceived as low-pitched sounds. The audible range of sound frequencies is between 20 and 20000 Hz, with greatest sensitivity to those frequencies that fall in the middle of this range.

As was the case with the visible spectrum, other species show differences in their audible ranges. For instance, chickens have a very limited audible range, from 125 to 2000 Hz. Mice have an audible range from 1000 to 91000 Hz, and the beluga whale’s audible range is from 1000 to 123000 Hz. Our pet dogs and cats have audible ranges of about 70–45000 Hz and 45–64000 Hz, respectively (Strain, 2003).

The loudness of a given sound is closely associated with the amplitude of the sound wave. Higher amplitudes are associated with louder sounds. Loudness is measured in terms of decibels (dB), a logarithmic unit of sound intensity. A typical conversation would correlate with 60 dB; a rock concert might check in at 120 dB ([link]). A whisper 5 feet away or rustling leaves are at the low end of our hearing range; sounds like a window air conditioner, a normal conversation, and even heavy traffic or a vacuum cleaner are within a tolerable range. However, there is the potential for hearing damage from about 80 dB to 130 dB: These are sounds of a food processor, power lawnmower, heavy truck (25 feet away), subway train (20 feet away), live rock music, and a jackhammer. The threshold for pain is about 130 dB, a jet plane taking off or a revolver firing at close range (Dunkle, 1982).

This figure illustrates the loudness of common sounds. (credit “planes”: modification of work by Max Pfandl; credit “crowd”: modification of work by Christian Holmér; credit “blender”: modification of work by Jo Brodie; credit “car”: modification of work by NRMA New Cars/Flickr; credit “talking”: modification of work by Joi Ito; credit “leaves”: modification of work by Aurelijus Valeiša)

Although wave amplitude is generally associated with loudness, there is some interaction between frequency and amplitude in our perception of loudness within the audible range. For example, a 10 Hz sound wave is inaudible no matter the amplitude of the wave. A 1000 Hz sound wave, on the other hand, would vary dramatically in terms of perceived loudness as the amplitude of the wave increased.

Link to Learning

Watch this brief video demonstrating how frequency and amplitude interact in our perception of loudness.

Of course, different musical instruments can play the same musical note at the same level of loudness, yet they still sound quite different. This is known as the timbre of a sound. Timbre refers to a sound’s purity, and it is affected by the complex interplay of frequency, amplitude, and timing of sound waves.

Link to Learning

Watch this video that provides additional information on sound waves.

Summary

Both light and sound can be described in terms of wave forms with physical characteristics like amplitude, wavelength, and timbre. Wavelength and frequency are inversely related so that longer waves have lower frequencies, and shorter waves have higher frequencies. In the visual system, a light wave’s wavelength is generally associated with color, and its amplitude is associated with brightness. In the auditory system, a sound’s frequency is associated with pitch, and its amplitude is associated with loudness.

Self Check Questions

Critical Thinking Question

1. Why do you think other species have such different ranges of sensitivity for both visual and auditory stimuli compared to humans?

2. Why do you think humans are especially sensitive to sounds with frequencies that fall in the middle portion of the audible range?

Personal Application Question

3. If you grew up with a family pet, then you have surely noticed that they often seem to hear things that you don’t hear. Now that you’ve read this section, you probably have some insight as to why this may be. How would you explain this to a friend who never had the opportunity to take a class like this?

Answers

1. Other species have evolved to best suit their particular environmental niches. For example, the honeybee relies on flowering plants for survival. Seeing in the ultraviolet light might prove especially helpful when locating flowers. Once a flower is found, the ultraviolet rays point to the center of the flower where the pollen and nectar are contained. Similar arguments could be made for infrared detection in snakes as well as for the differences in audible ranges of the species described in this section.

2. Once again, one could make an evolutionary argument here. Given that the human voice falls in this middle range and the importance of communication among humans, one could argue that it is quite adaptive to have an audible range that centers on this particular type of stimulus.

Glossary

Candela Citations

- Psychology. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/4abf04bf-93a0-45c3-9cbc-2cefd46e68cc@4.100:1/Psychology. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/content/col11629/latest/.