- Where can investors buy and sell securities, and how are securities markets regulated?

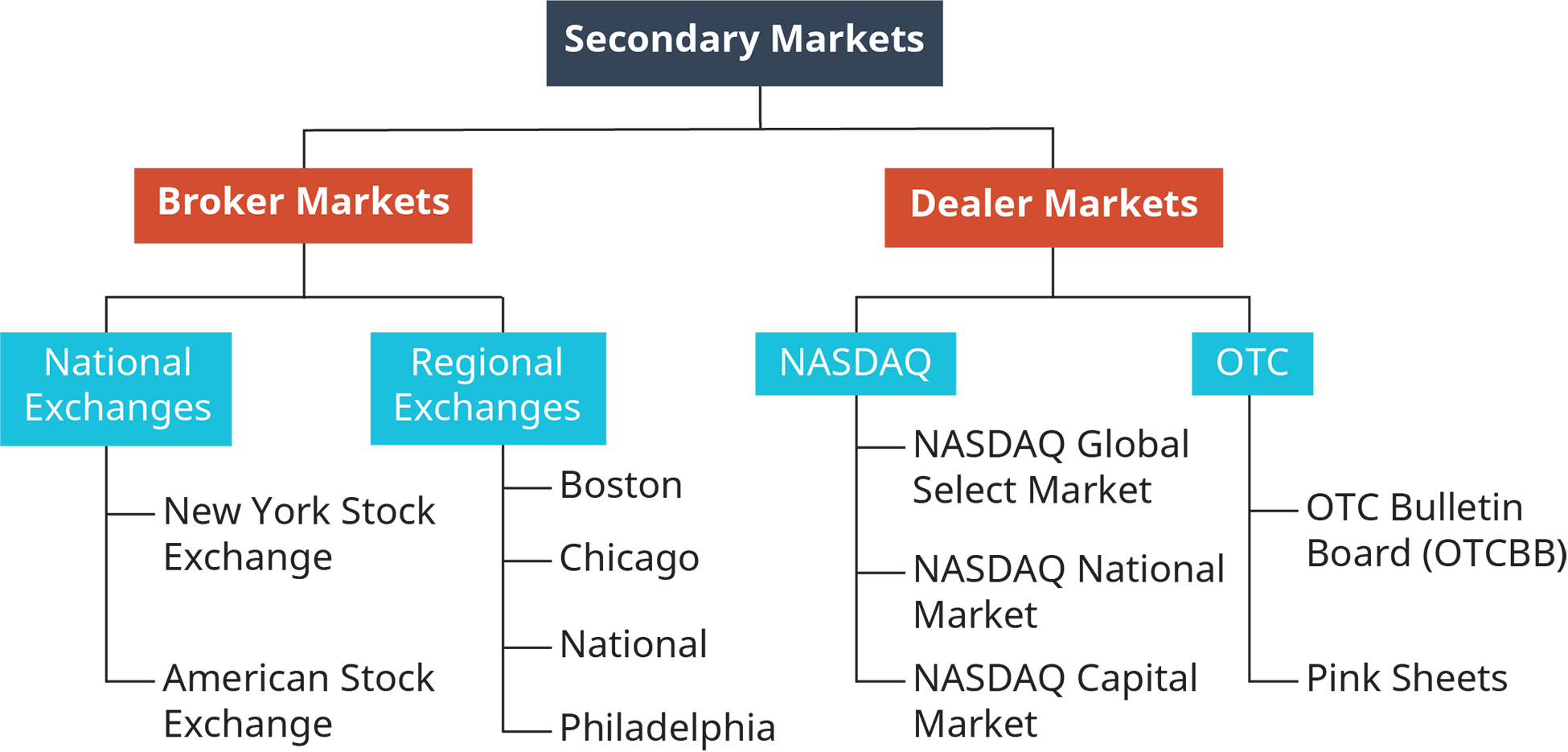

When we think of stock markets, we are typically referring to secondary markets, which handle most of the securities trading activity. The two segments of the secondary markets are broker markets and dealer markets, as (Figure) shows. The primary difference between broker and dealer markets is the way each executes securities trades. Securities trades can also take place in alternative market systems and on non-U.S. securities exchanges.

The securities markets both in the United States and around the world are in flux and undergoing tremendous changes. We present the basics of securities exchanges in this section and discuss the latest trends in the global securities markets later in the chapter.

Broker Markets

The broker market consists of national and regional securities exchanges that bring buyers and sellers together through brokers on a centralized trading floor. In the broker market, the buyer purchases the securities directly from the seller through the broker. Broker markets account for about 60 percent of the total dollar volume of all shares traded in the U.S. securities markets.

Exhibit 16.1 The Secondary Markets: Broker and Dealer Markets (Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license.)

New York Stock Exchange

The oldest and most prestigious broker market is the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), which has existed since 1792. Often called the Big Board, it is located on Wall Street in downtown New York City. The NYSE, which lists the shares of some 2,400 corporations, had a total market capitalization (domestic and foreign companies) of $25.8 trillion at year-end 2016. On a typical day, more than 3 billion shares of stock are traded on the NYSE.[1] It represents 90 percent of the trading volume in the U.S. broker marketplace. Major companies such as IBM, Coca-Cola, AT&T, Procter & Gamble, Ford Motor Co., and Chevron list their shares on the NYSE. Companies that list on the NYSE must meet stringent listing requirements and annual maintenance requirements, which give them creditability.

The NYSE is also popular with non-U.S. companies. More than 490 foreign companies with a global market capitalization of almost $63 trillion now list their securities on the NYSE.[2]

Until recently, all NYSE transactions occurred on the vast NYSE trading floor. Each of the companies traded at the NYSE is assigned to a trading post on the floor. When an exchange member receives an order to buy or sell a particular stock, the order is transmitted to a floor broker at the company’s trading post. The floor brokers then compete with other brokers on the trading floor to get the best price for their customers.

In response to competitive pressures from electronic exchanges, the NYSE created a hybrid market that combines features of the floor auction market and automated trading. Its customers now have a choice of how they execute trades. In the trends section, we’ll discuss other changes the NYSE is making to maintain a leadership position among securities exchanges.

Another national stock exchange, the American Stock Exchange (AMEX), lists the securities of more than 700 corporations but handles only 4 percent of the annual share volume of shares traded on U.S. securities exchanges. Because the AMEX’s rules are less strict than those of the NYSE, most AMEX firms are smaller and less well known than NYSE-listed corporations. Some firms move up to the NYSE once they qualify for listing there. Other companies choose to remain on the AMEX. Companies cannot be listed on both exchanges at the same time. The AMEX has become a major market, however, for exchange-traded funds and in options trading.

Exhibit 16.7 The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) is the largest securities market in the world. Its market capitalization dwarfs both foreign and domestic markets. Unlike other financial markets, the NYSE trades mostly through specialists, financial professionals who match up buyers and sellers of securities, while pocketing the spread between the bid and ask price on market orders. How does the NYSE’s hybrid trading system differ from fully automated, electronic trading? (Credit: Kevin Hutchison/ flickr/ Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0))

Regional Exchanges

The remaining 6 percent of annual share volume takes place on several regional exchanges in the United States. These exchanges list about 100 to 500 securities of firms located in their area. Regional exchange membership rules are much less strict than for the NYSE. The top regional exchanges are the Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, and National (formerly the Cincinnati) exchanges. An electronic network linking the NYSE and many of the regional exchanges allows brokers to make securities transactions at the best prices.

The regional exchanges, which have struggled to compete, benefited from the passage of the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC’s) Regulation NMS (National Market System), which became fully effective in 2007. Regulation NMS makes price the most important factor in making securities trades, and all orders must go to the trading venue with the best price.[3]

Dealer Markets

Unlike broker markets, dealer markets do not operate on centralized trading floors but instead use sophisticated telecommunications networks that link dealers throughout the United States. Buyers and sellers do not trade securities directly, as they do in broker markets. They work through securities dealers called market makers, who make markets in one or more securities and offer to buy or sell securities at stated prices. A security transaction in the dealer market has two parts: the selling investor sells his or her securities to one dealer, and the buyer purchases the securities from another dealer (or in some cases, the same dealer).

Exhibit 16.8 The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) named Stacy Cunningham the first female head of the exchange in its 226-year history. Outside the exchange, the statue “Fearless Girl” by Kristen Virbal stared down the “bull” statue and represented the need for more female representation on the world’s most important exchange. How does the naming of Stacy Cunningham as head of the NYSE demonstrate that the glass ceiling has been shattered? (Anthony Quintano/ Flickr/ Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0))

NASDAQ

The largest dealer market is the National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotation system, commonly referred to as NASDAQ. The first electronic-based stock market, the NASDAQ is a sophisticated telecommunications network that links dealers throughout the United States. Founded in 1971 with origins in the over-the-counter (OTC) market, today NASDAQ is a separate securities exchange that is no longer part of the OTC market. The NASDAQ lists more companies than the NYSE, but the NYSE still leads in total market capitalization. An average of 1.6 billion shares were exchanged daily in 2016 through NASDAQ, which is now the largest electronic stock market.[4] It provides up-to-date bid and ask prices on about 3,700 of the most active OTC securities. Its sophisticated electronic communication system provides faster transaction speeds than traditional floor markets and is the main reason for the popularity and growth of the OTC market.

In January 2006, the SEC approved NASDAQ’s application to operate as a national securities exchange. As a result, the NASDAQ Stock Market LLC began operating independently in August 2006.[5] The securities of many well-known companies, some of which could be listed on the organized exchanges, trade on the NASDAQ. Examples include Amazon, Apple, Costco, Comcast, JetBlue, Microsoft, Qualcomm, and Starbucks. The stocks of most commercial banks and insurance companies also trade in this market, as do most government and corporate bonds. More than 400 foreign companies also trade on the NASDAQ.

More than a decade ago, the NASDAQ changed its structure to a three-tier market:

- The NASDAQ Global Select Market, a new tier with “financial and liquidity requirements that are higher than those of any other market,” according to NASDAQ. More than 1,000 NASDAQ companies qualify for this group.

- The NASDAQ Global Market (formerly the NASDAQ National Market), which will list about 1,650 companies.

- The NASDAQ Capital Market will replace the NASDAQ Small Cap Market and list about 550 companies.

All three market tiers adhere to NASDAQ’s rigorous listing and corporate governance standards.[6]

The Over-the-Counter Market

The over-the-counter (OTC) markets refer to those other than the organized exchanges described above. There are two OTC markets: the Over-the-Counter Bulletin Board (OTCBB) and the Pink Sheets. These markets generally list small companies and have no listing or maintenance standards, making them attractive to young companies looking for funding. OTC companies do not have to file with the SEC or follow the costly provisions of Sarbanes-Oxley. Investing in OTC companies is therefore highly risky and should be for experienced investors only.

Alternative Trading Systems

In addition to broker and dealer markets, alternative trading systems such as electronic communications networks (ECNs) make securities transactions. ECNs are private trading networks that allow institutional traders and some individuals to make direct transactions in what is called the fourth market. ECNs bypass brokers and dealers to automatically match electronic buy and sell orders. They are most effective for high-volume, actively traded stocks. Money managers and institutions such as pension funds and mutual funds with large amounts of money to invest like ECNs because they cost far less than other trading venues.

Global Trading and Foreign Exchanges

Improved communications and the elimination of many legal barriers are helping the securities markets go global. The number of securities listed on exchanges in more than one country is growing. Foreign securities are now traded in the United States. Likewise, foreign investors can easily buy U.S. securities.

Stock markets also exist in foreign countries: more than 60 countries operate their own securities exchanges. NASDAQ ranks second to the NYSE, followed by the London Stock Exchange (LSE) and the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Other important foreign stock exchanges include Euronext (which merged with the NYSE but operates separately) and those in Toronto, Frankfurt, Hong Kong, Zurich, Australia, Paris, and Taiwan.[7] The number of big U.S. corporations with listings on foreign exchanges is growing steadily, especially in Europe. For example, significant activity in NYSE-listed stocks also occurs on the LSE. The LSE also is getting a growing share of the world’s IPOs. Emerging markets such as India, whose economy has been growing 6 percent or more a year, continue to attract investor attention. The Sensex, the benchmark index of the Bombay Stock Exchange, increased close to 40 percent between 2013 and 2017 as foreign investors continue to pump billions into Indian stocks.[8]

Why should U.S. investors pay attention to international stock markets? Because the world’s economies are increasingly interdependent, businesses must look beyond their own national borders to find materials to make their goods and markets for foreign goods and services. The same is true for investors, who may find that they can earn higher returns in international markets.

Regulation of Securities Markets

Both state and federal governments regulate the securities markets. The states were the first to pass laws aimed at preventing securities fraud. But most securities transactions occur across state lines, so federal securities laws are more effective. In addition to legislation, the industry has self-regulatory groups and measures.

Securities Legislation

Congress passed the Securities Act of 1933 in response to the 1929 stock market crash and subsequent problems during the Great Depression. It protects investors by requiring full disclosure of information about new securities issues. The issuer must file a registration statement with the SEC, which must be approved by the SEC before the security can be sold.

The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 formally gave the SEC power to regulate securities exchanges. The act was amended in 1964 to give the SEC authority over the dealer markets as well. The amendment included rules for operating the stock exchanges and granted the SEC control over all participants (exchange members, brokers, dealers) and the securities traded in these markets.

The 1934 act also banned insider trading, the use of information that is not available to the general public to make profits on securities transactions. Because of lax enforcement, however, several big insider trading scandals occurred during the late 1980s. The Insider Trading and Fraud Act of 1988 greatly increased the penalties for illegal insider trading and gave the SEC more power to investigate and prosecute claims of illegal actions. The meaning of insider was expanded beyond a company’s directors, employees, and their relatives to include anyone who gets private information about a company.

Other important legislation includes the Investment Company Act of 1940, which gives the SEC the right to regulate the practices of investment companies (such as mutual funds managed by financial institutions), and the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, which requires investment advisers to disclose information about their background. The Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC) was established in 1970 to protect customers if a brokerage firm fails, by insuring each customer’s account for up to $500,000.

In response to corporate scandals that hurt thousands of investors, the SEC passed new regulations designed to restore public trust in the securities industry. It issued Regulation FD (for “fair disclosure”) in October 2000. Regulation FD requires public companies to share information with all investors at the same time, leveling the information playing field. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 has given the SEC more power when it comes to regulating how securities are offered, sold, and marketed.

Self-Regulation

The investment community also regulates itself, developing and enforcing ethical standards to reduce the potential for abuses in the financial marketplace. The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) oversees the nation’s more than 3,700 brokerage firms and more 600,000 registered brokers. It develops rules and regulations, provides a dispute resolution forum, and conducts regulatory reviews of member activities for the protection and benefit of investors.

In response to “Black Monday”—October 19, 1987, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged 508 points and the trading activity severely overloaded the exchange’s computers—the securities markets instituted corrective measures to prevent a repeat of the crisis. Now, under certain conditions, circuit breakers stop trading for a 15-minute cooling-off period to limit the amount the market can drop in one day. Under revised rules approved in 2012 by the SEC, market-wide circuit breakers kick in when the S&P 500 Index drops 7 percent (level 1), 13 percent (level 2), and 20 percent (level 3) from the prior day’s closing numbers.[9]

ethics in practice

As part of the 2010 Dodd-Frank legislation passed by Congress in response to the 2008 financial crisis, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) established a whistleblower-rewards program to provide employees and other individuals with the opportunity to report financial securities misconduct. More than seven years after starting the Office of the Whistleblower, the SEC reports that the rewards program has recovered almost $1 billion in financial penalties from companies that have done things to damage their own reputation as well as those of employees and other stakeholders.

According to a recent SEC report, 2016 was a banner year for individuals reporting financial wrongdoings and whistleblowers being rewarded for what they discovered. In 2016 alone, more than $57 million was awarded to whistleblowers—an amount greater than the total amount of rewards issued since the program’s inception in 2011.

The whistleblower program is based on three key components: monetary awards, prohibition of employer retaliation, and protection of the whistleblower’s identity. The program requires the SEC to pay out monetary awards to eligible individuals who voluntarily provide original information about a violation of federal securities laws that has occurred, is ongoing, or is about to take place. The information supplied must lead to a successful enforcement action or monetary sanctions exceeding $1 million. No awards are paid out until the sanctions are collected from the offending firm.

A whistleblower must be an individual (not a company), and that individual does not need to be employed by a company to submit information about that specific organization. A typical award to a whistleblower is between 10 and 30 percent of the monetary sanctions the SEC and others (for example, the U.S. attorney general) are able to collect from the company in question.

Through September 2016, the whistleblower program received more than 18,000 tips, with more than 4,200 tips reported in 2016 alone. The program is not limited to U.S. citizens or residents; foreign persons living abroad may submit tips and are eligible to receive a monetary award. In fact, the SEC gave the largest monetary award to date of $30 million to a foreign national living abroad for original information relating to an ongoing fraud.

Despite criticisms from some financial institutions, the whistleblower-rewards program continues to be a success—reinforcing the point that financial fraud will not go unnoticed by the SEC, employees, and others individuals.

- Despite assurances that companies involved in financial fraud are not allowed to retaliate against their accusers, would you blow the whistle on your employer? Why or why not?

- What can companies do to make sure their employees are aware of the consequences of financial securities fraud? Provide several examples.

Sources: “Office of the Whistleblower,” https://www.sec.gov, accessed November 1, 2017; Erika A. Kelton, “Four Important Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Program Developments to Watch for in 2017,” https://wp.nyu.edu, accessed November 1, 2017; Jason Zuckerman and Matt Stock, “One Billion Reasons Why the SEC Whistleblower-Reward Program Is Effective,” Forbes, http://www.forbes.com, July 18, 2017; John Maxfield, “The Dodd-Frank Act Explained,” USA Today, https://www.usatoday.com, February 3, 2017; Eduardo Singerman and Paul Hugel, “The Tremendous Impact of the Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Program in 2016,” Accounting Today, https://www.accountingtoday.com, December 28, 2016; Samuel Rubenfeld, “Dodd-Frank Rollback to Spare SEC Whistleblower Program, Experts Say,” The Wall Street Journal, https://www.blogs.wsj.com, November 15, 2016.

Key Takeaways

- How do the broker markets differ from dealer markets, and what organizations compose each of these two markets?

- Why is the globalization of the securities markets important to U.S. investors? What are some of the other exchanges where U.S companies can list their securities?

- Briefly describe the key provisions of the main federal laws designed to protect securities investors. What is insider trading, and how can it be harmful? How does the securities industry regulate itself?

Summary of Learning Outcomes

- Where can investors buy and sell securities, and how are securities markets regulated?

Securities are resold in secondary markets, which include both broker markets and dealer markets. The broker market consists of national and regional securities exchanges, such as the New York Stock Exchange, that bring buyers and sellers together through brokers on a centralized trading floor. Dealer markets use sophisticated telecommunications networks that link dealers throughout the United States. The NASDAQ and over-the-counter markets are examples of dealer markets. In addition to broker and dealer markets, electronic communications networks (ECNs) can be used to make securities transactions. In addition to the U.S. markets, more than 60 countries have securities exchanges. The largest non-U.S. exchanges are the London, Tokyo, Toronto, Frankfurt, Hong Kong, and Taiwan exchanges.

The Securities Act of 1933 requires disclosure of important information regarding new securities issues. The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and its 1964 amendment formally empowered the Securities and Exchange Commission and granted it broad powers to regulate the securities exchanges and the dealer markets. The Investment Company Act of 1940 places investment companies such as companies that issue mutual funds under SEC control. The securities markets also have self-regulatory groups such as the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) and measures such as “circuit breakers” to halt trading if the S&P 500 Index drops rapidly.

Glossary

- broker markets

- National and regional securities exchanges that bring buyers and sellers together through brokers on a centralized trading floor.

- circuit breakers

- Corrective measures that, under certain conditions, stop trading in the securities markets for a short cooling-off period to limit the amount the market can drop in one day.

- dealer markets

- Securities markets where buy and sell orders are executed through dealers, or “market makers,” linked by telecommunications networks.

- electronic communications networks (ECNs)

- Private trading networks that allow institutional traders and some individuals to make direct transactions in the fourth market.

- insider trading

- The use of information that is not available to the general public to make profits on securities transactions.

- National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotation (NASDAQ) system

- The first and largest electronic stock market, which is a sophisticated telecommunications network that links dealers throughout the United States.

- over-the-counter (OTC) market

- Markets, other than the exchanges, on which small companies trade; includes the Over-the-Counter Bulletin Board (OTCBB) and the Pink Sheets.

Candela Citations

- Intro to Business. Authored by: Gitman, et. al. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/4e09771f-a8aa-40ce-9063-aa58cc24e77f@8.2. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/4e09771f-a8aa-40ce-9063-aa58cc24e77f@8.2

- “Markets Diary: Closing Snapshot,” The Wall Street Journal, http://www.wsj.com, accessed October 11, 2017; “NYSE 2016 Year in Review,” https://www.nyse.com, accessed October 11, 2017. ↵

- “Non-U.S. Issuers Data,” https://www.nyse.com, accessed October 11, 2017. ↵

- John D’Antona, “The Reg NMS Debate Goes On and On,” https://marketsmedia.com, June 23, 2017. ↵

- “NASDAQ 2017/2016 Monthly Volumes,” http://www.nasdaq.com, accessed October 11, 2017. ↵

- “NASDAQ’s Story,” http://business.nasdaq.com, accessed October 12, 2017. ↵

- “NASDAQ’s Listing Markets,” http://business.nasdaq.com, accessed October 12, 2017. ↵

- Jeff Desjardins, “Here Are the 20 Biggest Stock Exchanges in the World,” Business Insider, http://www.businessinsider.com, April 11, 2017; Jeff Desjardins, “All of the World’s Stock Exchanges by Size,” Visual Capitalist, http://money.visualcapitalist.com, February 16, 2016. ↵

- “Indian Sensex Stock Market Index” and “Indian GDP Annual Growth Rate,” https://tradingeconomics.com, accessed October 12, 2017. ↵

- Zack Guzman and Mark Koba, “When Do Circuit Breakers Kick In? CNBC Explains,” CNBC, https://www.cnbc.com, January 8, 2016. ↵