Learning Objectives

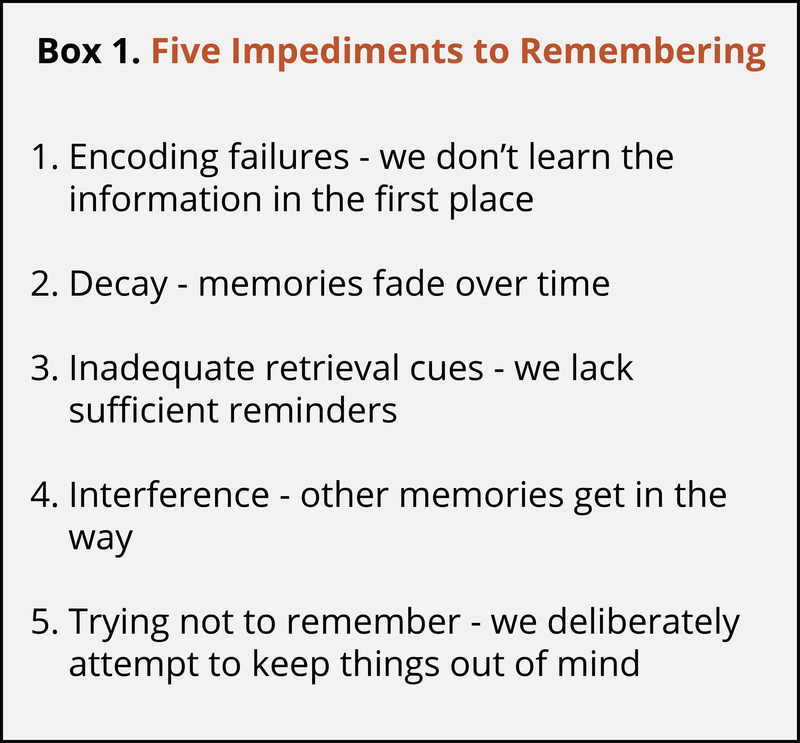

- Identify five reasons we forget and give examples of each.

- Describe how forgetting can be viewed as an adaptive process.

- Explain the difference between anterograde and retrograde amnesia.

Introduction

Chances are that you have experienced memory lapses and been frustrated by them. You may have had trouble remembering the definition of a key term on an exam or found yourself unable to recall the name of an actor from one of your favorite TV shows. Maybe you forgot to call your aunt on her birthday or you routinely forget where you put your cell phone. Oftentimes, the bit of information we are searching for comes back to us, but sometimes it does not. Clearly, forgetting seems to be a natural part of life. Why do we forget? And is forgetting always a bad thing?

![[Image: jazbeck, https://goo.gl/nkRrJy, CC BY 2.0, https://goo.gl/BRvSA7] A woman covers her face in embarrassment.](https://nobaproject.com/images/shared/images/000/002/136/original.jpg)

Forgetting can often be obnoxious or even embarrassing. But as we explore this module, you’ll learn that forgetting is important and necessary for everyday functionality.

Causes of Forgetting

One very common and obvious reason why you cannot remember a piece of information is because you did not learn it in the first place. If you fail to encode information into memory, you are not going to remember it later on. Usually, encoding failures occur because we are distracted or are not paying attention to specific details. For example, people have a lot of trouble recognizing an actual penny out of a set of drawings of very similar pennies, or lures, even though most of us have had a lifetime of experience handling pennies (Nickerson & Adams, 1979). However, few of us have studied the features of a penny in great detail, and since we have not attended to those details, we fail to recognize them later. Similarly, it has been well documented that distraction during learning impairs later memory (e.g., Craik, Govoni, Naveh-Benjamin, & Anderson, 1996). Most of the time this is not problematic, but in certain situations, such as when you are studying for an exam, failures to encode due to distraction can have serious repercussions.

Another proposed reason why we forget is that memories fade, or decay, over time. It has been known since the pioneering work of Hermann Ebbinghaus (1885/1913) that as time passes, memories get harder to recall. Ebbinghaus created more than 2,000 nonsense syllables, such as dax, bap, and rif, and studied his own memory for them, learning as many as 420 lists of 16 nonsense syllables for one experiment. He found that his memories diminished as time passed, with the most forgetting happening early on after learning. His observations and subsequent research suggested that if we do not rehearse a memory and the neural representation of that memory is not reactivated over a long period of time, the memory representation may disappear entirely or fade to the point where it can no longer be accessed. As you might imagine, it is hard to definitively prove that a memory has decayed as opposed to it being inaccessible for another reason. Critics argued that forgetting must be due to processes other than simply the passage of time, since disuse of a memory does not always guarantee forgetting (McGeoch, 1932). More recently, some memory theorists have proposed that recent memory traces may be degraded or disrupted by new experiences (Wixted, 2004). Memory traces need to be consolidated, or transferred from the hippocampus to more durable representations in the cortex, in order for them to last (McGaugh, 2000). When the consolidation process is interrupted by the encoding of other experiences, the memory trace for the original experience does not get fully developed and thus is forgotten.

Both encoding failures and decay account for more permanent forms of forgetting, in which the memory trace does not exist, but forgetting may also occur when a memory exists yet we temporarily cannot access it. This type of forgetting may occur when we lack the appropriate retrieval cues for bringing the memory to mind. You have probably had the frustrating experience of forgetting your password for an online site. Usually, the password has not been permanently forgotten; instead, you just need the right reminder to remember what it is. For example, if your password was “pizza0525,” and you received the password hints “favorite food” and “Mom’s birthday,” you would easily be able to retrieve it. Retrieval hints can bring back to mind seemingly forgotten memories (Tulving & Pearlstone, 1966). One real-life illustration of the importance of retrieval cues comes from a study showing that whereas people have difficulty recalling the names of high school classmates years after graduation, they are easily able to recognize the names and match them to the appropriate faces (Bahrick, Bahrick, & Wittinger, 1975). The names are powerful enough retrieval cues that they bring back the memories of the faces that went with them. The fact that the presence of the right retrieval cues is critical for remembering adds to the difficulty in proving that a memory is permanently forgotten as opposed to temporarily unavailable.

Retrieval failures can also occur because other memories are blocking or getting in the way of recalling the desired memory. This blocking is referred to as interference. For example, you may fail to remember the name of a town you visited with your family on summer vacation because the names of other towns you visited on that trip or on other trips come to mind instead. Those memories then prevent the desired memory from being retrieved. Interference is also relevant to the example of forgetting a password: passwords that we have used for other websites may come to mind and interfere with our ability to retrieve the desired password. Interference can be either proactive, in which old memories block the learning of new related memories, or retroactive, in which new memories block the retrieval of old related memories. For both types of interference, competition between memories seems to be key (Mensink & Raaijmakers, 1988). Your memory for a town you visited on vacation is unlikely to interfere with your ability to remember an Internet password, but it is likely to interfere with your ability to remember a different town’s name. Competition between memories can also lead to forgetting in a different way. Recalling a desired memory in the face of competition may result in the inhibition of related, competing memories (Levy & Anderson, 2002). You may have difficulty recalling the name of Kennebunkport, Maine, because other Maine towns, such as Bar Harbor, Winterport, and Camden, come to mind instead. However, if you are able to recall Kennebunkport despite strong competition from the other towns, this may actually change the competitive landscape, weakening memory for those other towns’ names, leading to forgetting of them instead.

Finally, some memories may be forgotten because we deliberately attempt to keep them out of mind. Over time, by actively trying not to remember an event, we can sometimes successfully keep the undesirable memory from being retrieved either by inhibiting the undesirable memory or generating diversionary thoughts (Anderson & Green, 2001). Imagine that you slipped and fell in your high school cafeteria during lunch time, and everyone at the surrounding tables laughed at you. You would likely wish to avoid thinking about that event and might try to prevent it from coming to mind. One way that you could accomplish this is by thinking of other, more positive, events that are associated with the cafeteria. Eventually, this memory may be suppressed to the point that it would only be retrieved with great difficulty (Hertel & Calcaterra, 2005).

Finally, some memories may be forgotten because we deliberately attempt to keep them out of mind. Over time, by actively trying not to remember an event, we can sometimes successfully keep the undesirable memory from being retrieved either by inhibiting the undesirable memory or generating diversionary thoughts (Anderson & Green, 2001). Imagine that you slipped and fell in your high school cafeteria during lunch time, and everyone at the surrounding tables laughed at you. You would likely wish to avoid thinking about that event and might try to prevent it from coming to mind. One way that you could accomplish this is by thinking of other, more positive, events that are associated with the cafeteria. Eventually, this memory may be suppressed to the point that it would only be retrieved with great difficulty (Hertel & Calcaterra, 2005).

Adaptive Forgetting

We have explored five different causes of forgetting. Together they can account for the day-to-day episodes of forgetting that each of us experience. Typically, we think of these episodes in a negative light and view forgetting as a memory failure. Is forgetting ever good? Most people would reason that forgetting that occurs in response to a deliberate attempt to keep an event out of mind is a good thing. No one wants to be constantly reminded of falling on their face in front of all of their friends. However, beyond that, it can be argued that forgetting is adaptive, allowing us to be efficient and hold onto only the most relevant memories (Bjork, 1989; Anderson & Milson, 1989). Shereshevsky, or “S,” the mnemonist studied by Alexander Luria (1968), was a man who almost never forgot. His memory appeared to be virtually limitless. He could memorize a table of 50 numbers in under 3 minutes and recall the numbers in rows, columns, or diagonals with ease. He could recall lists of words and passages that he had memorized over a decade before. Yet Shereshevsky found it difficult to function in his everyday life because he was constantly distracted by a flood of details and associations that sprung to mind. His case history suggests that remembering everything is not always a good thing. You may occasionally have trouble remembering where you parked your car, but imagine if every time you had to find your car, every single former parking space came to mind. The task would become impossibly difficult to sort through all of those irrelevant memories. Thus, forgetting is adaptive in that it makes us more efficient. The price of that efficiency is those moments when our memories seem to fail us (Schacter, 1999).

Amnesia

Clearly, remembering everything would be maladaptive, but what would it be like to remember nothing? We will now consider a profound form of forgetting called amnesia that is distinct from more ordinary forms of forgetting. Most of us have had exposure to the concept of amnesia through popular movies and television. Typically, in these fictionalized portrayals of amnesia, a character suffers some type of blow to the head and suddenly has no idea who they are and can no longer recognize their family or remember any events from their past. After some period of time (or another blow to the head), their memories come flooding back to them. Unfortunately, this portrayal of amnesia is not very accurate. What does amnesia typically look like?

![[Image: en:Anatomography, https://goo.gl/ALPAu6, CC BY-SA 2.1 JP, https://goo.gl/BDF2Z4] Model of the human brain with temporal lobes highlighted.](https://nobaproject.com/images/shared/images/000/002/609/original.png)

Patients with damage to the temporal lobes may experience anterograde amnesia and/or retrograde amnesia.

The most widely studied amnesic patient was known by his initials H. M. (Scoville & Milner, 1957). As a teenager, H. M. suffered from severe epilepsy, and in 1953, he underwent surgery to have both of his medial temporal lobes removed to relieve his epileptic seizures. The medial temporal lobes encompass the hippocampus and surrounding cortical tissue. Although the surgery was successful in reducing H. M.’s seizures and his general intelligence was preserved, the surgery left H. M. with a profound and permanent memory deficit. From the time of his surgery until his death in 2008, H. M. was unable to learn new information, a memory impairment called anterograde amnesia. H. M. could not remember any event that occurred since his surgery, including highly significant ones, such as the death of his father. He could not remember a conversation he had a few minutes prior or recognize the face of someone who had visited him that same day. He could keep information in his short-term, or working, memory, but when his attention turned to something else, that information was lost for good. It is important to note that H. M.’s memory impairment was restricted to declarative memory, or conscious memory for facts and events. H. M. could learn new motor skills and showed improvement on motor tasks even in the absence of any memory for having performed the task before (Corkin, 2002).

In addition to anterograde amnesia, H. M. also suffered from temporally graded retrograde amnesia. Retrograde amnesia refers to an inability to retrieve old memories that occurred before the onset of amnesia. Extensive retrograde amnesia in the absence of anterograde amnesia is very rare (Kopelman, 2000). More commonly, retrograde amnesia co-occurs with anterograde amnesia and shows a temporal gradient, in which memories closest in time to the onset of amnesia are lost, but more remote memories are retained (Hodges, 1994). In the case of H. M., he could remember events from his childhood, but he could not remember events that occurred a few years before the surgery.

Amnesiac patients with damage to the hippocampus and surrounding medial temporal lobes typically manifest a similar clinical profile as H. M. The degree of anterograde amnesia and retrograde amnesia depend on the extent of the medial temporal lobe damage, with greater damage associated with a more extensive impairment (Reed & Squire, 1998). Anterograde amnesia provides evidence for the role of the hippocampus in the formation of long-lasting declarative memories, as damage to the hippocampus results in an inability to create this type of new memory. Similarly, temporally graded retrograde amnesia can be seen as providing further evidence for the importance of memory consolidation (Squire & Alvarez, 1995). A memory depends on the hippocampus until it is consolidated and transferred into a more durable form that is stored in the cortex. According to this theory, an amnesiac patient like H. M. could remember events from his remote past because those memories were fully consolidated and no longer depended on the hippocampus.

The classic amnesiac syndrome we have considered here is sometimes referred to as organic amnesia, and it is distinct from functional, or dissociative, amnesia. Functional amnesia involves a loss of memory that cannot be attributed to brain injury or any obvious brain disease and is typically classified as a mental disorder rather than a neurological disorder (Kihlstrom, 2005). The clinical profile of dissociative amnesia is very different from that of patients who suffer from amnesia due to brain damage or deterioration. Individuals who experience dissociative amnesia often have a history of trauma. Their amnesia is retrograde, encompassing autobiographical memories from a portion of their past. In an extreme version of this disorder, people enter a dissociative fugue state, in which they lose most or all of their autobiographical memories and their sense of personal identity. They may be found wandering in a new location, unaware of who they are and how they got there. Dissociative amnesia is controversial, as both the causes and existence of it have been called into question. The memory loss associated with dissociative amnesia is much less likely to be permanent than it is in organic amnesia.

Conclusion

Just as the case study of the mnemonist Shereshevsky illustrates what a life with a near perfect memory would be like, amnesiac patients show us what a life without memory would be like. Each of the mechanisms we discussed that explain everyday forgetting—encoding failures, decay, insufficient retrieval cues, interference, and intentional attempts to forget—help to keep us highly efficient, retaining the important information and for the most part, forgetting the unimportant. Amnesiac patients allow us a glimpse into what life would be like if we suffered from profound forgetting and perhaps show us that our everyday lapses in memory are not so bad after all.

Key Takeaways

Anterograde amnesia

Inability to form new memories for facts and events after the onset of amnesia.

Consolidation

Process by which a memory trace is stabilized and transformed into a more durable form.

Decay

The fading of memories with the passage of time.

Declarative memory

Conscious memories for facts and events.

Dissociative amnesia

Loss of autobiographical memories from a period in the past in the absence of brain injury or disease.

Encoding

Process by which information gets into memory.

Interference

Other memories get in the way of retrieving a desired memory

Medial temporal lobes

Inner region of the temporal lobes that includes the hippocampus.

Retrieval

Process by which information is accessed from memory and utilized.

Retrograde amnesia

Inability to retrieve memories for facts and events acquired before the onset of amnesia.

Temporally graded retrograde amnesia

Inability to retrieve memories from just prior to the onset of amnesia with intact memory for more remote events.

Candela Citations

- Authored by: Dudukovic, N. & Kuhl, B. (2024). Forgetting and amnesia. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers.. Located at: . License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. License Terms: Forgetting and Amnesia by Nicole Dudukovic and Brice Kuhl is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.