We have learned about cognitive development from infancy through adolescence, ending with Piaget’s stage of formal operations. Does that mean that cognitive development stops with adolescence? Couldn’t there be different ways of thinking in adulthood that come after (or “post”) formal operations?

In this section, we will learn about these types of postformal operational thought and consider research done by William Perry related to types of thought and advanced thinking. We will also look at education in early adulthood, the relationship between education and work, and some tools used by young adults to choose their careers.

Cognitive Development in Early Adulthood

Beyond Formal Operational Thought: Postformal Thought

Figure 1. As young adults gain more experience, they think increasingly more in the abstract and are able to understand different perspectives and complexities.

In the adolescence module, we discussed Piaget’s formal operational thought. The hallmark of this type of thinking is the ability to think abstractly or to consider possibilities and ideas about circumstances never directly experienced. Thinking abstractly is only one characteristic of adult thought, however. If you compare a 14-year-old with someone in their late 30s, you would probably find that the later considers not only what is possible, but also what is likely. Why the change? The young adult has gained experience and understands why possibilities do not always become realities. This difference in adult and adolescent thought can spark arguments between the generations.

Here is an example. A student in her late 30s relayed such an argument she was having with her 14-year-old son. The son had saved a considerable amount of money and wanted to buy an old car and store it in the garage until he was old enough to drive. He could sit in it, pretend he was driving, clean it up, and show it to his friends. It sounded like a perfect opportunity. The mother, however, had practical objections. The car would just sit for several years while deteriorating. The son would probably change his mind about the type of car he wanted by the time he was old enough to drive and they would be stuck with a car that would not run. She was also concerned that having a car nearby would be too much temptation and the son might decide to sneak it out for a quick ride before he had a permit or license.

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development ended with formal operations, but it is possible that other ways of thinking may develop after (or “post”) formal operations in adulthood (even if this thinking does not constitute a separate “stage” of development). Postformal thought is practical, realistic and more individualistic, but also characterized by understanding the complexities of various perspectives. As a person approaches the late 30s, chances are they make decisions out of necessity or because of prior experience and are less influenced by what others think. Of course, this is particularly true in individualistic cultures such as the United States. Postformal thought is often described as more flexible, logical, willing to accept moral and intellectual complexities, and dialectical than previous stages in development.

Try It

Perry’s Scheme

One of the first theories of cognitive development in early adulthood originated with William Perry (1970), who studied undergraduate students at Harvard University. Perry noted that over the course of students’ college years, cognition tended to shift from dualism (absolute, black and white, right and wrong type of thinking) to multiplicity (recognizing that some problems are solvable and some answers are not yet known) to relativism (understanding the importance of the specific context of knowledge—it’s all relative to other factors). Similar to Piaget’s formal operational thinking in adolescence, this change in thinking in early adulthood is affected by educational experiences.

Video 1. Perry’s Scheme of Intellectual Development.

| Table 1. Stages of Perry’s Scheme | ||

|---|---|---|

| Summary of Position in Perry’s Scheme | Basic Example | |

| Dualism | The authorities know | “the tutor knows what is right and wrong” |

| The true authorities are right, the others are frauds | “my tutor doesn’t know what is right and wrong but others do” | |

| Multiplicity | There are some uncertainties and the authorities are working on them to find the truth | “my tutors don’t know, but somebody out there is trying to find out” |

| (a) Everyone has the right to their own opinion (b) The authorities don’t want the right answers. They want us to think in a certain way |

“different tutors think different things” “there is an answer that the tutors want and we have to find it” |

|

| Relativism | Everything is relative but not equally valid | “there are no right and wrong answers, it depends on the situation, but some answers might be better than others” |

| You have to make your own decisions | “what is important is not what the tutor thinks but what I think” | |

| First commitment | “for this particular topic I think that….” | |

| Several Commitments | “for these topics I think that….” | |

| Believe own values, respect others, be ready to learn | “I know what I believe in and what I think is valid, others may think differently and I’m prepared to reconsider my views” | |

Dialectical Thought

In addition to moving toward more practical considerations, thinking in early adulthood may also become more flexible and balanced. Abstract ideas that the adolescent believes in firmly may become standards by which the individual evaluates reality. As Perry’s research pointed out, adolescents tend to think in dichotomies or absolute terms; ideas are true or false; good or bad; right or wrong and there is no middle ground. However, with education and experience, the young adult comes to recognize that there is some right and some wrong in each position. Such thinking is more realistic because very few positions, ideas, situations, or people are completely right or wrong.

Some adults may move even beyond the relativistic or contextual thinking described by Perry; they may be able to bring together important aspects of two opposing viewpoints or positions, synthesize them, and come up with new ideas. This is referred to as dialectical thought and is considered one of the most advanced aspects of postformal thinking (Basseches, 1984). There isn’t just one theory of postformal thought; there are variations, with emphasis on adults’ ability to tolerate ambiguity or to accept contradictions or find new problems, rather than solve problems, etc. (as well as relativism and dialecticism that we just learned about). What they all have in common is the proposition that the way we think may change during adulthood with education and experience.

Try It

Schaie and Willis’ Stage Theory of Cognition

Another perspective on post-formal cognitive development focuses less on the development of cognitive skills and instead discerns the changes in the use of intellect. Shaie and Willis’ stage theory of cognition proposed several stages of adult cognitive development.

Figure 2. Shaie & Willis’ Stage Theory of Cognition.

Figure 2. Shaie & Willis’ Stage Theory of Cognition.

During childhood and adolescence, cognition is about the acquisition of new knowledge and skills. These young people may not yet know how they will use these acquired skills. In early adulthood, people switch their focus from the acquisition to the application of knowledge, as they use what they know to pursue

careers and develop their families. This is called the achieving stage. It represents most prominently the application of intelligence in situations that have

profound consequences for achieving long-term goals. The kind of intelligence exhibited in such situations is similar to that employed in educational tasks, but it

requires careful attention to the possible consequences of the problem-solving process.

Adults who have mastered the cognitive skills required for monitoring their own behavior and, as a consequence, have attained a certain degree of personal

independence will next move into a stage that requires the application of cognitive skills in situations involving social responsibility. Typically, the responsible stage

occurs when a family is established and the needs of a spouse and offspring must be met. Similar extensions of adult cognitive skills are required as responsibilities for others are acquired on the job and in the community.

Some individualsʼ responsibilities become exceedingly complex. Such individuals-presidents of business firms, deans of academic institutions, officials

of churches, and a number of other positions-need to understand the structure and the dynamic forces of organizations. They must monitor organizational

activities not only on a temporal dimension (past, present, and future), but also up and down the hierarchy that defines the organization. They need to know not

only the future plans of the organization but also whether policy decisions are being adequately translated into action at lower levels of responsibility. Attainment of the executive stage, as a variation on the responsibility stage, depends on exposure to opportunities that allow the development and practice of the relevant skills (Avolio, 1991; Smith, Staudinger, & Baltes, 1994).

In the later years of life, beyond the age of 60 or 65, the need to acquire knowledge declines even more, and executive monitoring is less important because

frequently the individual has retired from the position that required such an application of intelligence. This stage, reintegration, corresponds in its position in the life

course to Eriksonʼs stage of ego integrity. The information that elderly people acquire and the knowledge they apply becomes a function of their interests, attitudes,

and values. It requires, in fact, the reintegration of all of these. The elderly are less likely to “waste time” on tasks that are meaningless to them. They are unlikely to

expend much effort to solve a problem unless that problem is one that they face frequently in their lives. This stage frequently includes a selective reduction of

interpersonal networks in the interest of reintegrating oneʼs concern in a more self-directed and supportive manner (cf. Carstensen, 1993; Carstensen, Gross, & Fung, 1997). In addition, efforts must be directed towards planning how oneʼs resources will last for the remaining 15 to 30 years of post-retirement life that are now characteristic for most individuals in industrialized societies. These efforts include active planning for that time when dependence upon others may be required to maintain a high quality of life in the face of increasing frailty. Such efforts may involve changes in oneʼs housing arrangements, or even oneʼs place of residence, as well as making certain of the eventual availability of both familial and extra-familial support systems. The activities involved in this context include making or changing oneʼs will, drawing up advanced medical directives and durable powers of attorney, as well as creating trusts or other financial arrangements that will protect resources for use during the final years of life or for the needs of other family members.

Although some of these activities involve the same cognitive characteristics of the responsible stage, these objectives involved are far more centered upon current

and future needs of the individual rather than the needs of their family or of an organizational entity. Efforts must now be initiated to reorganize oneʼs time and resources to substitute a meaningful environment, often found in leisure activities, volunteerism, and involvement with a larger kinship network. Eventually, however, activities are also engaged in maximizing the quality of life during the final years, often with the additional objective of not becoming a burden for the next generation. The unique objective of these demands upon the individual represent an almost universal process occurring at least in the industrialized societies, and designation of a separate reorganizational stage is therefore warranted. The skills required for the reorganizational stage require the maintenance of reasonably high levels of cognitive competence. In addition, maintenance of flexible cognitive styles are needed to be able to restructure the context and content of life after

retirement, to relinquish control of resources to others and to accept the partial surrender of oneʼs independence (Schaie, 1984; 2005).

Many older persons reach advanced old age in relative comfort and often with a clear mind albeit a frail body. Once the reintegrative efforts described above

have been successfully completed, yet one other stage is frequently observed. This last stage is concerned with cognitive activities by many of the very old that occur in anticipation of the end of their life. This is a legacy stage that is part of the cognitive development of many, if not all, older persons. This stage often begins

by the effort to conduct a life review (Butler, Lewis, & Sunderland, 1998). For the highly literate and those successful in public or professional life this will often include writing or revising an autobiography (Birren, Kenyon, Ruth, Schroots, & Swensson, 1995; Birren & Schroots, 2006). There are also many other more mundane legacies to be left. Women, in particular, often wish to put their remaining effects in order and often distribute many of their prized possessions to friends and relatives, or create elaborate instructions for distributing them. It is not uncommon for many very old people to make a renewed effort at providing an oral history or to explain family pictures and heirloom to the next generation. Last, but not least, directions may be given for funeral arrangements, occasionally including the donation of oneʼs body for scientific research, and there may be a final revision of oneʼs will.

Education and Work

Education in Early Adulthood

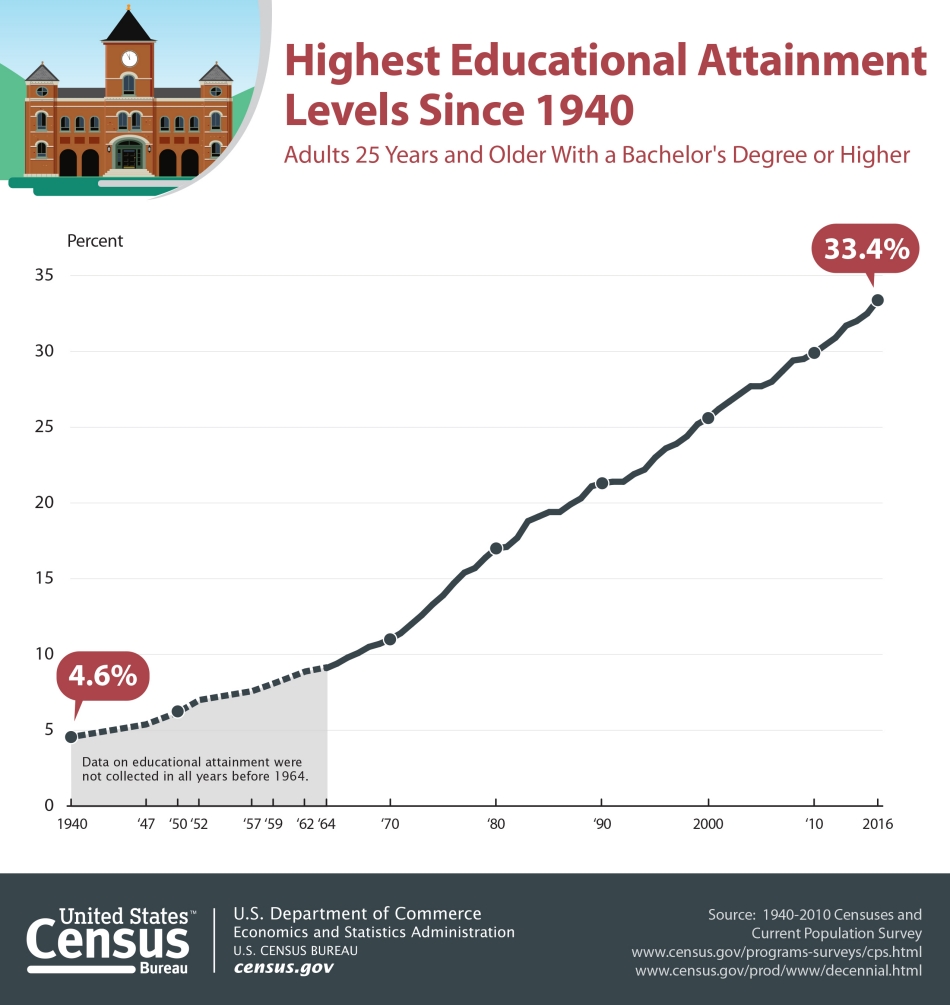

According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2017), 90 percent of the American population 25 and older have completed high school or higher level of education—compare this to just 24 percent in 1940! Each generation tends to earn (and perhaps need) increased levels of formal education. As we can see in the graph, approximately one-third of the American adult population has a bachelor’s degree or higher, as compared with less than 5 percent in 1940. Educational attainment rates vary by gender and race. All races combined, women are slightly more likely to have graduated from college than men; that gap widens with graduate and professional degrees. However, wide racial disparities still exist. For example, 23 percent of African-Americans have a college degree and only 16.4 percent of Hispanic Americans have a college degree, compared to 37 percent of non-Hispanic white Americans. The college graduation rates of African-Americans and Hispanic Americans have been growing in recent years, however (the rate has doubled since 1991 for African-Americans and it has increased 60 percent in the last two decades for Hispanic-Americans).

Figure 2. Since 1940, there has been a significant rise in educational attainment for adults over age 25.

Try It

Education and the Workplace

With the rising costs of higher education, various news headlines have asked if a college education is worth the cost. One way to address this question is in terms of the earning potential associated with various levels of educational achievement. In 2016, the average earnings for Americans 25 and older with only a high school education was $35,615, compared with $65,482 for those with a bachelor’s degree, compared with $92,525 for those with more advanced degrees. Average earnings vary by gender, race, and geographical location in the United States.

Of concern in recent years is the relationship between higher education and the workplace. In 2005, American educator and then Harvard University President, Derek Bok, called for a closer alignment between the goals of educators and the demands of the economy. Companies outsource much of their work, not only to save costs but to find workers with the skills they need. What is required to do well in today’s economy? Colleges and universities, he argued, need to promote global awareness, critical thinking skills, the ability to communicate, moral reasoning, and responsibility in their students. Regional accrediting agencies and state organizations provide similar guidelines for educators. Workers need skills in listening, reading, writing, speaking, global awareness, critical thinking, civility, and computer literacy—all skills that enhance success in the workplace.

More than a decade later, the question remains: does formal education prepare young adults for the workplace? It depends on whom you ask. In an article referring to information from the National Association of Colleges and Employers’ 2018 Job Outlook Survey, Bauer-Wolf (2018) explains that employers perceive gaps in students’ competencies but many graduating college seniors are overly confident. The biggest difference was in perceived professionalism and work ethic (only 43 percent of employers thought that students are competent in this area compared to 90 percent of the students). Similar differences were also found in terms of oral communication, written communication, and critical thinking skills. Only in terms of digital technology skills were more employers confident about students’ competencies than were the students (66 percent compared to 60 percent).

It appears that students need to learn what some call “soft skills,” as well as the particular knowledge and skills within their college major. As education researcher Loni Bordoloi Pazich (2018) noted, most American college students today are enrolling in business or other pre-professional programs and to be effective and successful workers and leaders, they would benefit from the communication, teamwork, and critical thinking skills, as well as the content knowledge, gained from liberal arts education. In fact, two-thirds of children starting primary school now will be employed in jobs in the future that currently do not exist. Therefore, students cannot learn every single skill or fact that they may need to know, but they can learn how to learn, think, research, and communicate well so that they are prepared to continually learn new things and adapt effectively in their careers and lives since the economy, technology, and global markets will continue to evolve.

Career Choices in Early Adulthood

Hopefully, we are each becoming lifelong learners, particularly since we are living longer and will most likely change jobs multiple times during our lives. However, for many, our job changes will be within the same general occupational field, so our initial career choice is still significant. We’ve seen with Erikson that identity largely involves occupation and, as we will learn in the next section, Levinson found that young adults typically form a dream about work (though females may have to choose to focus relatively more on work or family initially with “split” dreams). The American School Counselor Association recommends that school counselors aid students in their career development beginning as early as kindergarten and continue this development throughout their education.

One of the most well-known theories about career choice is from John Holland (1985), who proposed that there are six personality types (realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, and conventional), as well as varying types of work environments. The better matched one’s personality is to the workplace characteristics, the more satisfied and successful one is predicted to be with that career or vocational choice. Research support has been mixed and we should note that there is more to satisfaction and success in a career than one’s personality traits or likes and dislikes. For instance, education, training, and abilities need to match the expectations and demands of the job, plus the state of the economy, availability of positions, and salary rates may play practical roles in choices about work.

Link to Learning: What’s Your Right Career?

To complete a free online career questionnaire and identify potential careers based on your preferences, go to:

Did you find out anything interesting? Think of this activity as a starting point to your career exploration. Other great ways for young adults to research careers include informational interviewing, job shadowing, volunteering, practicums, and internships. Once you have a few careers in mind that you want to find out more about, go to the Occupational Outlook Handbook from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics to learn about job tasks, required education, average pay, and projected outlook for the future.

Try It

Candela Citations

- Introduction to Cognitive Development in Early Adulthood. Authored by: Margaret Clark-Plaskie for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by: Margaret Clark-Plaskie. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Young Woman. Authored by: Karolina Grabowska. Located at: https://pixabay.com/images/id-791849/. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology. Authored by: Laura Overstreet. Located at: http://opencourselibrary.org/econ-201/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Millennials Jam Workshop: Youth and ICTs beyond 2015. Authored by: ITU Pictures. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/itupictures/9024333319. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Summary of Perry's research. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_G._Perry. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Postformal thought. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Postformal_thought. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Perry's Scheme of Intellectual Development. Authored by: Eric Landrum. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XkEJIXvwROs. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Highest Educational Levels Reached by Adults in the U.S. Since 1940. Provided by: U.S. Census Bureau. Located at: https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2017/comm/cb17-51_educational_attainment.html. License: All Rights Reserved