Learning Objectives

- Describe different types of personality tests, including the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory and common projective tests

- Describe the complications of developing personality assessments, including the importance of reliability and validity

Personality tests are techniques designed to measure one’s personality. They are used to diagnose psychological problems as well as to screen candidates for college and employment. There are two types of personality tests: self-report inventories and projective tests. The MMPI is one of the most common self-report inventories. It asks a series of true/false questions that are designed to provide a clinical profile of an individual. Projective tests use ambiguous images or other ambiguous stimuli to assess an individual’s unconscious fears, desires, and challenges. The Rorschach Inkblot Test, the TAT, the RISB, and the C-TCB are all forms of projective tests.

Roberto, Mikhail, and Nat are college friends and all want to be police officers. Roberto is quiet and shy, lacks self-confidence, and usually follows others. He is a kind person, but lacks motivation. Mikhail is loud and boisterous, a leader. He works hard, but is impulsive and drinks too much on the weekends. Nat is thoughtful and well liked. He is trustworthy, but sometimes he has difficulty making quick decisions. Of these three men, who would make the best police officer? What qualities and personality factors make someone a good police officer? What makes someone a bad or dangerous police officer?

A police officer’s job is very high in stress, and law enforcement agencies want to make sure they hire the right people. Personality testing is often used for this purpose—to screen applicants for employment and job training. Personality tests are also used in criminal cases and custody battles, and to assess psychological disorders. This section explores the best known among the many different types of personality tests.

Video 1. Trait Theory of Personality.

Self-Report Inventories

Self-report inventories are a kind of objective test used to assess personality. They typically use multiple-choice items or numbered scales, which represent a range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). They often are called Likert scales after their developer, Rensis Likert (1932) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. If you’ve ever taken a survey, you are probably familiar with Likert-type scale questions. Most personality inventories employ these types of response scales.

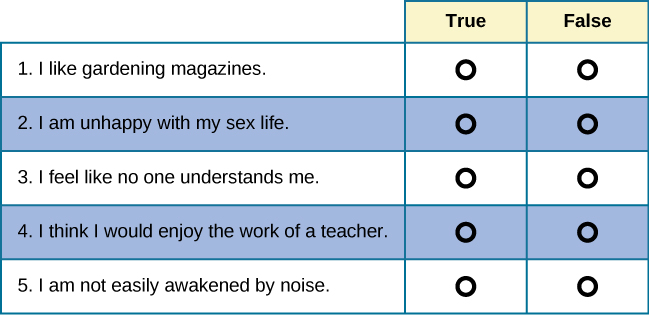

One of the most widely used personality inventories is the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), first published in 1943, with 504 true/false questions, and updated to the MMPI-2 in 1989, with 567 questions. The original MMPI was based on a small, limited sample, composed mostly of Minnesota farmers and psychiatric patients; the revised inventory was based on a more representative, national sample to allow for better standardization. The MMPI-2 takes 1–2 hours to complete. Responses are scored to produce a clinical profile composed of 10 scales: hypochondriasis, depression, hysteria, psychopathic deviance (social deviance), masculinity versus femininity, paranoia, psychasthenia (obsessive/compulsive qualities), schizophrenia, hypomania, and social introversion. There is also a scale to ascertain risk factors for alcohol abuse. In 2008, the test was again revised, using more advanced methods, to the MMPI-2-RF. This version takes about one-half the time to complete and has only 338 questions (Figure 2). Despite the new test’s advantages, the MMPI-2 is more established and is still more widely used. Typically, the tests are administered by computer. Although the MMPI was originally developed to assist in the clinical diagnosis of psychological disorders, it is now also used for occupational screening, such as in law enforcement, and in college, career, and marital counseling (Ben-Porath & Tellegen, 2008).

Figure 2. These true/false questions resemble the kinds of questions you would find on the MMPI.

In addition to clinical scales, the tests also have validity and reliability scales. (Recall the concepts of reliability and validity from your study of psychological research.) One of the validity scales, the Lie Scale (or “L” Scale), consists of 15 items and is used to ascertain whether the respondent is “faking good” (underreporting psychological problems to appear healthier). For example, if someone responds “yes” to a number of unrealistically positive items such as “I have never told a lie,” they may be trying to “fake good” or appear better than they actually are.

Reliability scales test an instrument’s consistency over time, assuring that if you take the MMPI-2-RF today and then again 5 years later, your two scores will be similar. Beutler, Nussbaum, and Meredith (1988) gave the MMPI to newly recruited police officers and then to the same police officers 2 years later. After 2 years on the job, police officers’ responses indicated an increased vulnerability to alcoholism, somatic symptoms (vague, unexplained physical complaints), and anxiety. When the test was given an additional 2 years later (4 years after starting on the job), the results suggested high risk for alcohol-related difficulties.

Projective Tests

Another method for assessment of personality is projective testing. This kind of test relies on one of the defense mechanisms proposed by Freud—projection—as a way to assess unconscious processes. During this type of testing, a series of ambiguous cards is shown to the person being tested, who then is encouraged to project his feelings, impulses, and desires onto the cards—by telling a story, interpreting an image, or completing a sentence. Many projective tests have undergone standardization procedures (for example, Exner, 2002) and can be used to access whether someone has unusual thoughts or a high level of anxiety, or is likely to become volatile. Some examples of projective tests are the Rorschach Inkblot Test, the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), the Contemporized-Themes Concerning Blacks test, the TEMAS (Tell-Me-A-Story), and the Rotter Incomplete Sentence Blank (RISB).

The Rorschach Inkblot Test was developed in 1921 by a Swiss psychologist named Hermann Rorschach (pronounced “ROAR-shock”). It is a series of symmetrical inkblot cards that are presented to a client by a psychologist. Upon presentation of each card, the psychologist asks the client, “What might this be?” What the test-taker sees reveals unconscious feelings and struggles (Piotrowski, 1987; Weiner, 2003). The Rorschach has been standardized using the Exner system and is effective in measuring depression, psychosis, and anxiety.

A second projective test is the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), created in the 1930s by Henry Murray, an American psychologist, and a psychoanalyst named Christiana Morgan. A person taking the TAT is shown 8–12 ambiguous pictures and is asked to tell a story about each picture. The stories give insight into their social world, revealing hopes, fears, interests, and goals. The storytelling format helps to lower a person’s resistance divulging unconscious personal details (Cramer, 2004). The TAT has been used in clinical settings to evaluate psychological disorders; more recently, it has been used in counseling settings to help clients gain a better understanding of themselves and achieve personal growth. Standardization of test administration is virtually nonexistent among clinicians, and the test tends to be modest to low on validity and reliability (Aronow, Weiss, & Rezinkoff, 2001; Lilienfeld, Wood, & Garb, 2000). Despite these shortcomings, the TAT has been one of the most widely used projective tests.

A third projective test is the Rotter Incomplete Sentence Blank (RISB) developed by Julian Rotter in 1950 (recall his theory of locus of control, covered earlier in this chapter). There are three forms of this test for use with different age groups: the school form, the college form, and the adult form. The tests include 40 incomplete sentences that people are asked to complete as quickly as possible (Figure 3). The average time for completing the test is approximately 20 minutes, as responses are only 1–2 words in length. This test is similar to a word association test, and like other types of projective tests, it is presumed that responses will reveal desires, fears, and struggles. The RISB is used in screening college students for adjustment problems and in career counseling (Holaday, Smith, & Sherry, 2010; Rotter & Rafferty 1950).

Figure 3. These incomplete sentences resemble the types of questions on the RISB. How would you complete these sentences?

For many decades, these traditional projective tests have been used in cross-cultural personality assessments. However, it was found that test bias limited their usefulness (Hoy-Watkins & Jenkins-Moore, 2008). It is difficult to assess the personalities and lifestyles of members of widely divergent ethnic/cultural groups using personality instruments based on data from a single culture or race (Hoy-Watkins & Jenkins-Moore, 2008). For example, when the TAT was used with African-American test takers, the result was often shorter story length and low levels of cultural identification (Duzant, 2005). Therefore, it was vital to develop other personality assessments that explored factors such as race, language, and level of acculturation (Hoy-Watkins & Jenkins-Moore, 2008). To address this need, Robert Williams developed the first culturally specific projective test designed to reflect the everyday life experiences of African Americans (Hoy-Watkins & Jenkins-Moore, 2008). The updated version of the instrument is the Contemporized-Themes Concerning Blacks Test (C-TCB) (Williams, 1972). The C-TCB contains 20 color images that show scenes of African-American lifestyles. When the C-TCB was compared with the TAT for African Americans, it was found that use of the C-TCB led to increased story length, higher degrees of positive feelings, and stronger identification with the C-TCB (Hoy, 1997; Hoy-Watkins & Jenkins-Moore, 2008).

The TEMAS Multicultural Thematic Apperception Test is another tool designed to be culturally relevant to minority groups, especially Hispanic youths. TEMAS—standing for “Tell Me a Story” but also a play on the Spanish word temas (themes)—uses images and storytelling cues that relate to minority culture (Constantino, 1982).

Try It

https://assessments.lumenlearning.com/assessments/4622

Think It Over

- How objective do you think you can be about yourself in answering questions on self-report personality assessment measures? What implications might this have for the validity of the personality test?

Part 1: Creating a Personality Questionnaire

Psychologists often assess a person’s personality using a questionnaire that is filled in by the person who is being assessed. Such a tests is called a “self-report inventory.” To get into the spirit of personality assessment, please complete the personality inventory below. It has only 10 questions. Simply decide much each pair of words or phrases fits you.

Take the TIPI Personality Test

The questionnaire you just completed is called the TIPI: The Ten-Item Personality Inventory. It was created by University of Texas psychologist Sam Gosling as a very brief measure of five personality characteristics: Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional Stability, and Openness to Experience. These five personality dimensions are called “The Big Five” and, taken together, they have been found to be an excellent first-level summary of people’s personality.

Tests of the Big Five personality dimensions are widely used by researchers and by people in business and education who want a general view of a person’s personality. There are several different self-report inventories that have been developed to measure the Big Five traits, most with 50 or more questions. The TIPI, which you just took, was developed for situations where time is very limited and the tester (usually a researcher) needs a “good enough” version of the test. One of the longer versions would be used by someone needing a more reliable and nuanced view of someone’s personality.

Looking at the TIPI, you might have the impression that creating a personality inventory is pretty easy. You come up with a few obvious questions, find names that fit, and you’re ready to claim you are measuring something about people’s personality.

Undoubtedly you can find some “personality tests” on the internet that fit this description, but tests created by serious psychologists for use in research or in clinical settings must go through a much more careful development process before they are widely accepted and used. And, even then, the tests continue to be studied, criticized, and revised.

In this exercise, we will look more closely at some of the work that goes into creating a personality inventory or questionnaire. To help you keep your eyes on the process of test construction, we want you to think about a personality dimension that is not as obvious as self-esteem or extraversion. We are going to assess blirtatiousness.

Part 1: Creating the Blirt Scale

One of my closest friends is sometimes annoying and usually entertaining, but he never holds back; you always know what he’s thinking. His wife is kind and friendly, and she is first to arrive when help is needed, but she hides her feelings and opinions. It is not easy to know what she wants or where she stands.

Consider your own closest friends. Where do they fall on the continuum between my friends? Who is open and easy to read, and who is private and guarded?

Back in the early 2000s, social psychologist William Swann and his colleagues became interested in the impact of self-disclosure—the process of communicating information about ourselves to other people—on personal relationships. In one paper, the researchers wrote about “blirters” and “brooders”—good labels for my two friends. Early in their research, the psychologists realized that the story was not going to be simple. Enthusiastic self-disclosure (blirting) is sometimes good for relationships and sometimes bad, and the same is true about reluctance to self-disclose (brooding).

The researchers also realized that they didn’t really have a good way to sort people out on the self-disclosure continuum. Self-selection (“I’m very open.” “I’m very private.”) often doesn’t fit with how other people—including your friends—see you. And researchers’ first impressions (“He seems like a blirter.” “She seems like a brooder.”) are extremely unreliable. They needed a better way to measure people’s willingness to self-disclose.

In this exercise, we’re going to give you a small taste of the process of creating a personality questionnaire. To do this, we are going to re-create Dr. Swann’s “blirtatiousness” test that is now used by researchers studying self-disclosure in personal relationships.

By the way, even serious psychologists seem to want to give their tests interesting names, so the name BLIRT stands for Brief Loquaciousness and Interpersonal Responsiveness Test.

Scale Construction: What Questions Should We Use?

The first step in constructing a test or scale to measure some personal characteristic is to be clear about what it is you are measuring. In their papers, Dr. Swann and his colleagues discuss what they mean by “blirtatiousness” in detail, but here the following definition should be enough: Blirtatiousness is the extent to which people respond to friends and partners quickly and effusively. A person is effusive if they excitedly show and express emotion.

One thing to notice about this definition is that it focuses on behavior more than inner feelings. It is the behaviors of our friends and partners that affect us, regardless of their intentions and motivations, so that is what the BLIRT scale is all about.

Obviously, the first step in creating a questionnaire is writing the questions, but this is not as straightforward as it seems. Will they be open-ended (e.g., “How open-minded are you? ___). Probably not, as they are hard to score. Forced-choice, where a person chooses one of several options, is a better choice. Some forced-choice questions make you give rankings, or others may have you choose from options, like these questions from the Narcissistic Personality Inventory:

Figure 1. The questions from Terry Raskin’s Narcissistic Personality Inventory force participants to choose between two options.

Another common forced-choice format is the Likert[1] scale, which is composed of a statement (not a question) followed by 5 or 7 numbers allowing you to indicate your level of agreement with the statement. For example, here is an item from the Rosenberg Self-Esteem inventory:

Dr. Swann and his team chose a 7-point Likert format to measure blirtatiousness. To do this, they needed to write clear, simple statements that people could agree or disagree with, where different levels of agreement were possible.

We aren’t going to ask you to write any questions, but join the test-development team by looking at the eight statements below. Choose four that you think would be the best items to include in the BLIRT scale.

When they were developing the scale, Dr. Swann and his team wrote dozens of questions, and then pared them down to 20. Then, they got 237 undergraduates to rate the 20 questions for how well they fit the qualities that the BLIRT scale was trying to measure.[2]

Questionnaire writers have strategies to encourage people to read the statements carefully. For example, they often write “reverse scoring” items. To show what this means, just below is the 7-point Likert scale used with the Blirtatiousness questionnaire. Below that you will see two statements. Look at how the statements and the Likert scale fit together.

- I speak my mind as soon as a thought enters my head.

- For this question, 1 means not blirtatious and 7 means very blirtatious.

- I speak my mind as soon as a thought enters my head.

- For this question, 1 means very blirtatious and 7 means not blirtatious.

Dr. Swann and his team chose 8 items for the BLIRT scale and half were worded so that higher numbers mean more blirtatious, and half so that high numbers mean less blirtatious. After the test, a process called “reverse scoring” put all the questions back on the same scale, so that higher numbers mean more blirtatious.[3]

At this point in the test-creation process, Dr. Swann and his team settled on eight statements that seemed to measure BLIRT. They were ready to administer the test, but before they could praise the test and its effectiveness, they needed to be sure of a few things: the questions need to work together as a set, the test must be reliable, and the test must be valid.

- The questions must work together as a set. In other words, we want to be sure that the 8 items are all giving us responses about the same quality (blirtatiousness) and that the responses people are giving are consistent with one another.

- You might think that a single question would be enough to measure blirtatiousness. Why ask 8 questions when one would do? But research has shown that asking variations on the same question 8 or 10 different times gives a more stable measure. The questions must be slightly different (enough to make people think carefully), but not too different (so they measure different things).

- The researchers administered the BLIRT to 1,137 students and used statistical procedures[4] to be sure that the 8 items in the scale worked together. The results indicated that the 8 items on the scale were consistent with each other in measuring the same psychological quality.

- The test must be reliable. The word “reliability” means “consistent.” We should be able to give you a test of some quality (e.g., how extraverted you are) and then give you that same test again two months later, and your scores should be pretty similar. This is important for what are called “stable traits”. Obviously, some psychological qualities, like moods, change all the time and we would not expect consistency. But blirtatiousness should be a stable trait.

- One common way to measure reliability of a test is a process called “test-retest reliability.” It is as simple as it sounds: you give the test, wait some period of time, and give again to the same people.

Try It

https://assessments.lumenlearning.com/assessments/13607

- The test must be valid. Believe it or not, after all this work, we still don’t know if the BLIRT scale is VALID. Validity is a question of whether or not we are measuring the thing we are trying to measure. Reliability doesn’t tell us if a scale is valid; reliability simply means that we get consistent answers. So how can we figure out if our test is valid or not? We’ll go into that in the next section.

The exercises you just reviewed give you a taste of the initial steps in creating a personality inventory. We started by carefully defining the personality trait. We had to figure out how we were going to ask our questions, and we chose a Likert scale. The questions had to be carefully written to be clear and focused on the trait we are studying: blirtatiousness. Writing effective items usually involves a process of writing, testing, selection, rewriting, retesting, and selecting again, until we are satisfied that our questions are good. Once we have compiled a test–at least a candidate for the test–we need to administer it to people to see if it is reliable and internally consistent (i.e., that all the questions are measuring the same trait).

Measuring Personality

Before you go on, now is a good time to measure your blirtatiousness. Follow the link below to find out if you are a blirter or a brooder.

Part 2: Does the Blirt Scale Measure What It Claims to Measure?

No one wants to use a scale that hasn’t been shown to be valid. And validity is really hard to show.

Analyzing Validity

Here is our challenge. Remember that blirtatiousness is the extent to which people respond to friends and partners quickly and effusively. Our questions may look good, but we need evidence that the numbers we get actually measure the trait.

There is no one way to determine the validity of a scale. Test developers like Dr. Swann usually take several different approaches. They may compare the test results with other personality tests of similar traits (convergent validity), or compare scores from the BLIRT test with other dissimilar tests (discriminant validity). Researchers may also compare the results of the BLIRT test to real-world outcomes (criterion validity), or see if the results work to predict people’s behavior in certain situations (predictive validity).

In the sections below, we will peek at some studies that try to assess these different aspects of validity.

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

One way to test the validity of a test is to compare it to results from tests of other traits for which validated tests already exist. There are two types of comparisons that researchers look for when they validate a test. One is called convergent validity and the other is called discriminant validity.

When testing for convergent validity, the researcher looks for other traits that are similar to (but not identical to) the trait they are measuring. For example, we are studying blirtatiousness. It would be reasonable to think that a person who is blirtatious is also assertive. The two traits—blirtatiousness and assertiveness—are not the same, but they are certainly related. If our blirtatiousness scale is not at all related to assertiveness, then we should be worried that we are not really measuring blirtatiousness successfully.

We can use the correlation between the BLIRT score and a score on a test of assertiveness to measure convergent validity. The researchers gave a set of tests, including the BLIRT scale and a measure of assertiveness[5] to 1,397 college students. Assertiveness was just one of several traits that were expected to be similar to blirtatiousness.[6]

Try It

https://assessments.lumenlearning.com/assessments/13608

We want our BLIRT score to have a moderate-to-strong relationship with traits that are similar, but we also want it to be unrelated to traits or abilities that are not similar to blirtatiousness. Tests of discriminant validity compare our BLIRT score to traits that should have weak or no relationship to blirtatiousness. For example, people who are blirtatious may be good students or poor students or somewhere in-between. Knowing how blirtatious you are should not tell us much about how good a student you are.

The researchers compared the BLIRT score of the 1,397 students mentioned earlier to their self-reported GPA.[7]

Try It

https://assessments.lumenlearning.com/assessments/13609

Dr. Swann’s team compared 21 different traits and abilities to the blirtatiousness scale. Some assessed convergent validity and others tested discriminant validity. The results were generally convincing: BLIRT scores were similar to traits that should be related to blirtatiousness (good convergent validity) and unrelated to traits that should have no connection to blirtatiousness (good discriminant validity).

Criterion Validity

Another way to test the validity of a measure is to see if it fits the way people behave in the real world. The BLIRT researchers conducted two studies to see if BLIRT scores fit what we know about people’s personalities. Criterion validity is the relationship between some measure and some real-world outcome.

Librarians or Salespeople?

Who do you think is more likely to be blirtatious, a salesperson or a librarian? The researchers found thirty employees of car dealerships and libraries in central Texas and gave them the BLIRT scale. Their ages ranged from 20 to 66 (average age = 34.3 years).

Try It

Using the bar graph below, adjust the bars based on your prediction about who will be more blirtatious. Then click the link below to see if your prediction is correct.

Most people expect salespeople to be more blirtatious than librarians. The researchers explained that we assume that high blirters will look for a work environment that rewards “effusive, rapid responding,” while low blirters would prefer a workplace that encourages “reflection and social inhibition.” As you can see, the results of the study were consistent with this idea: salespeople had significantly higher blirt scores (on the average) than librarians.

Asian Americans or European Americans?

How blirtatious a person is can be influenced by a lot of factors, including “cultural norms”—ways of acting that we learn from our families and the people around us as we grow up. Although we shouldn’t overstate the difference, Asian cultures tend to emphasize restraint of emotional expression, while European cultures are more likely to encourage direct and rapid expression.

The researchers were able to get BLIRT scores from 2,800 students from European-American cultures and 698 students from Asian-American cultures. What would you predict about the BLIRT scores for these two groups?

Try It

Using the bar graph below, adjust the bars based on your prediction about who will be more blirtatious. Then click the link below to see if your prediction is correct.

As you can see, the results were consistent with the researchers’ expectations. The difference between the groups was small, but statistically significant. The small difference indicates that we shouldn’t turn these modest differences into cultural stereotypes, but the statistically significant difference suggests that cultural experiences may have a real—if modest—effect on people’s blirtatiousness.

Predictive Validity

Another way to assess validity of the BLIRT scale is to see if it predicts people’s behavior in specific situations. Based on research about first impressions, the experimenters believed that people who are open and expressive should, in general, make better first impressions than people who are reserved and relatively quiet.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers recruited college students and put them into pairs. The members of each pair had a 7-minute “getting acquainted” telephone conversation. The members of the pairs did not know each other and, in fact, they never saw each other. The participants also completed several personality measures, including the BLIRT scale. Note that they were NOT paired based on their BLIRT scores, so there were different combinations of blirtatiousness across the 32 pairs tested.

Try It

After the conversations, the students rated their conversation partners on several different qualities. For example, who do you think would be perceived as more responsive—a high blirter or a low blirter?

- high blirter

- low blirter

- no difference

Keeping in mind that this was a first-impression 7-minute conversation, who do you think would be seen as more interesting: a high blirter or a low blirter?

- high blirter

- low blirter

- no difference

Here are some other qualities that were rated. Make your prediction for each one, and then check out the results.

Who was rated as more likeable?

- high blirter

- low blirter

- no difference

Who was rated as someone who “I’d like to be friends with?”

- high blirter

- low blirter

- no difference

Who was rated as more intelligent?

- high blirter

- low blirter

- no difference

Measuring Personality

You now know more about creating a personality test than most people do. Scales like the BLIRT or the Big Five test you took at the beginning of this exercise are used for serious purposes. Psychological researchers use them in their studies, of course. But psychological tests are also used by companies in their hiring process, by therapists trying to understand their patients, school systems assessing strengths and weaknesses of their students, and even sports teams trying to identify the best athletes to fit their system.

Blirtatiousness is simply an example of a personality trait, and it is not among the most widely used scales. There are hundreds of personality tests in use today. For example, the Big Five personality traits (conscientiousness, agreeability, neuroticism, openness to experience, and extraversion) are among the most widely used scales, and they have been extensively studied and validated. Other qualities, like intelligence, self-esteem, and general anxiety level, have also been widely studied, and they have well validated measures.

We hope that this exercise has given you some insight into the characteristics of a good personality test, and the work that goes into developing a useful scale. Next time you take one, consider the process that went into its development.

Glossary

- Contemporized-Themes Concerning Blacks Test (C-TCB):

- projective test designed to be culturally relevant to African Americans, using images that relate to African-American culture

- convergent validity

- the relationship between traits that are similar to (but not identical to) the trait being measured

- criterion validity

- the relationship between some measure and some real-world outcome

- discriminant validity

- the relationship between some traits that should have weak or no relationship

- Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI):

- personality test composed of a series of true/false questions in order to establish a clinical profile of an individual

- predictive validity:

- the relationship between experimental results and the ability to predict people’s behavior in certain situations

- projective test:

- personality assessment in which a person responds to ambiguous stimuli, revealing hidden feelings, impulses, and desires

- Rorschach Inkblot Test:

- projective test that employs a series of symmetrical inkblot cards that are presented to a client by a psychologist in an effort to reveal the person’s unconscious desires, fears, and struggles

- Rotter Incomplete Sentence Blank (RISB):

- projective test that is similar to a word association test in which a person completes sentences in order to reveal their unconscious desires, fears, and struggles

- TEMAS Multicultural Thematic Apperception Test:

- projective test designed to be culturally relevant to minority groups, especially Hispanic youths, using images and storytelling that relate to minority culture

- Thematic Apperception Test (TAT):

- projective test in which people are presented with ambiguous images, and they then make up stories to go with the images in an effort to uncover their unconscious desires, fears, and struggles

https://assessments.lumenlearning.com/assessments/4858

Candela Citations

- Psychology in Real Life: Blirtatiousness, Questionnaires, and Validity. Authored by: Patrick Carroll for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Personality Assessment. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@5.52:Lsg7ohsh@4/Personality-Assessment. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/content/col11629/latest/.

- Personality building image. Authored by: Vic. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/59632563@N04/6235678871. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Measuring Personality: Crash Course Psychology #22. Provided by: CrashCourse. Located at: https://youtu.be/sUrV6oZ3zsk?list=PL8dPuuaLjXtOPRKzVLY0jJY-uHOH9KVU6. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Sample of narcissistic personality disorder. Authored by: Raskin, R.; Terry, H. Provided by: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Located at: https://openpsychometrics.org/tests/NPI/. Project: A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. License: All Rights Reserved

- Sample of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem inventory. Authored by: Morris Rosenberg. Located at: https://openpsychometrics.org/tests/RSE.php. Project: Society and the adolescent self-image. License: All Rights Reserved

- The man who created the scale pronounced his name as LICK-ert. Many psychologists—maybe even your instructor—pronounce it LIKE-ert. It probably doesn’t matter much which way you say the name. ↵

- Note: Notice that the four items from the BLIRT are about what you DO. They aren’t about your beliefs (option 1), how you think other people see you (option 3), opinions about yourself (option 4), or what you think about other people (option 6). ↵

- Reverse scoring is simple: 7 becomes 1, 6 becomes 2, 5 becomes 3, 4 stays 4, 3 becomes 5, 2 becomes 6, and 1 becomes 7. Only the 4 items with the reverse wording are rescored this way. The goal is to make it so that higher numbers mean more blirtatious for all the items. ↵

- Cronbach’s alpha and Factor Analysis ↵

- The Rathus Assertiveness Schedule ↵

- Others included self-perceived social confidence, extraversion, impulsivity, and self-liking. ↵

- Other traits assessed for discriminant validity were agreeableness, conscientiousness, affect intensity (how strongly people were influenced by their emotions). ↵