“What the educator does in teaching is to make it possible for the students to become themselves” (Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed). David Simon, in his book Social Problems and the Sociological Imagination: A Paradigm for Analysis (1995), points to the notion that social problems are, in essence, contradictions—that is, statements, ideas, or features of a situation that are opposed to one another. Consider then, that one of the greatest expectations in U.S. society is that to attain any form of success in life, a person needs an education. In fact, a college degree is rapidly becoming an expectation at nearly all levels of middle-class success, not merely an enhancement to our occupational choices. And, as you might expect, the number of people graduating from college in the United States continues to rise dramatically.

The contradiction, however, lies in the fact that the more necessary a college degree has become, the harder it has become to achieve it. The cost of getting a college degree has risen sharply since the mid-1980s, while government support in the form of Pell Grants has barely increased. The net result is that those who do graduate from college are likely to begin a career in debt. As of 2013, the average of amount of a typical student’s loans amounted to around $29,000. Added to that is that employment opportunities have not met expectations. The Washington Post (Brad Plumer May 20, 2013) notes that in 2010, only 27 percent of college graduates had a job related to their major. The business publication Bloomberg News states that among twenty-two-year-old degree holders who found jobs in the past three years, more than half were in roles not even requiring a college diploma (Janet Lorin and Jeanna Smialek, June 5, 2014).

Is a college degree still worth it? All this is not to say that lifetime earnings among those with a college degree are not, on average, still much higher than for those without. But even with unemployment among degree-earners at a low of 3 percent, the increase in wages over the past decade has remained at a flat 1 percent. And the pay gap between those with a degree and those without has continued to increase because wages for the rest have fallen (David Leonhardt, New York Times, The Upshot, May 27, 2014).

But is college worth more than money?

Generally, the first two years of college are essentially a liberal arts experience. The student is exposed to a fairly broad range of topics, from mathematics and the physical sciences to history and literature, the social sciences, and music and art through introductory and survey-styled courses. It is in this period that the student’s world view is, it is hoped, expanded. Memorization of raw data still occurs, but if the system works, the student now looks at a larger world. Then, when he or she begins the process of specialization, it is with a much broader perspective than might be otherwise. This additional “cultural capital” can further enrich the life of the student, enhance his or her ability to work with experienced professionals, and build wisdom upon knowledge. Two thousand years ago, Socrates said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” The real value of an education, then, is to enhance our skill at self-examination.

References

Leonhardt, David. 2014. “Is College Worth It? Clearly , New Data Say.” The New York Times. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

Lorin Janet, and Jeanna Smialek. 2014. “College Graduates Struggle to Find Eployment Worth a Degree.” Bloomberg. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

New Oxford English Dictionary. “contradiction.” New Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

Plumer, Brad. 2013. “Only 27 percent of college graduates have a job related ot their major.” The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

Simon, R David. 1995. Social Problems and the Sociological Imagination: A Paradigm for Analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

Education in the United States is a massive social institution involving millions of people and billions of dollars. About 75 million people, almost one-fourth of the U.S. population, attend school at all levels. This number includes 40 million in grades pre-K through 8, 16 million in high school, and 19 million in college (including graduate and professional school). They attend some 132,000 elementary and secondary schools and about 4,200 2-year and 4-year colleges and universities and are taught by about 4.8 million teachers and professors (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab Education is a huge social institution.

Correlates of Educational Attainment

About 65% of U.S. high school graduates enroll in college the following fall. This is a very high figure by international standards, as college in many other industrial nations is reserved for the very small percentage of the population who pass rigorous entrance exams. They are the best of the brightest in their nations, whereas higher education in the United States is open to all who graduate high school. Even though that is true, our chances of achieving a college degree are greatly determined at birth, as social class and race/ethnicity have a significant effect on access to college. They affect whether students drop out of high school, in which case they do not go on to college; they affect the chances of getting good grades in school and good scores on college entrance exams; they affect whether a family can afford to send its children to college; and they affect the chances of staying in college and obtaining a degree versus dropping out. For these reasons, educational attainment depends heavily on family income and race and ethnicity.

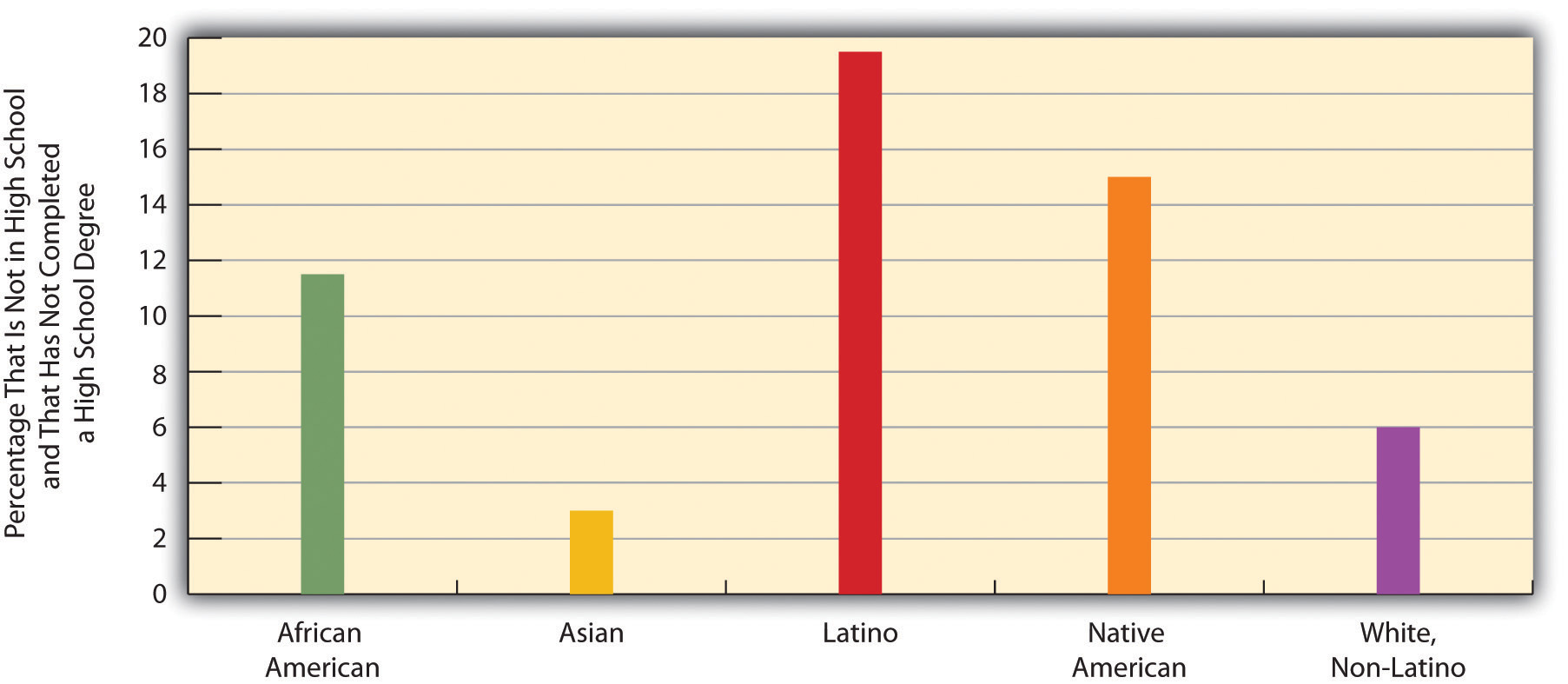

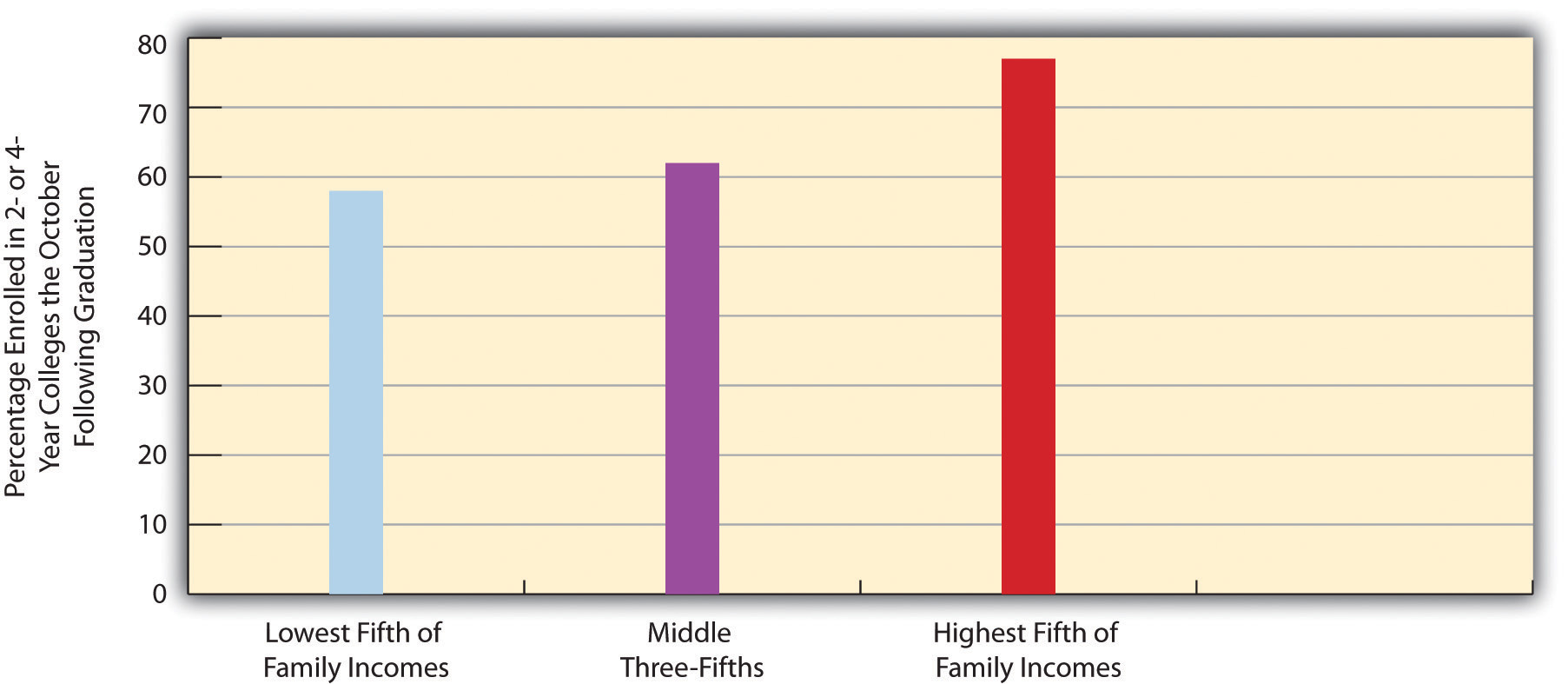

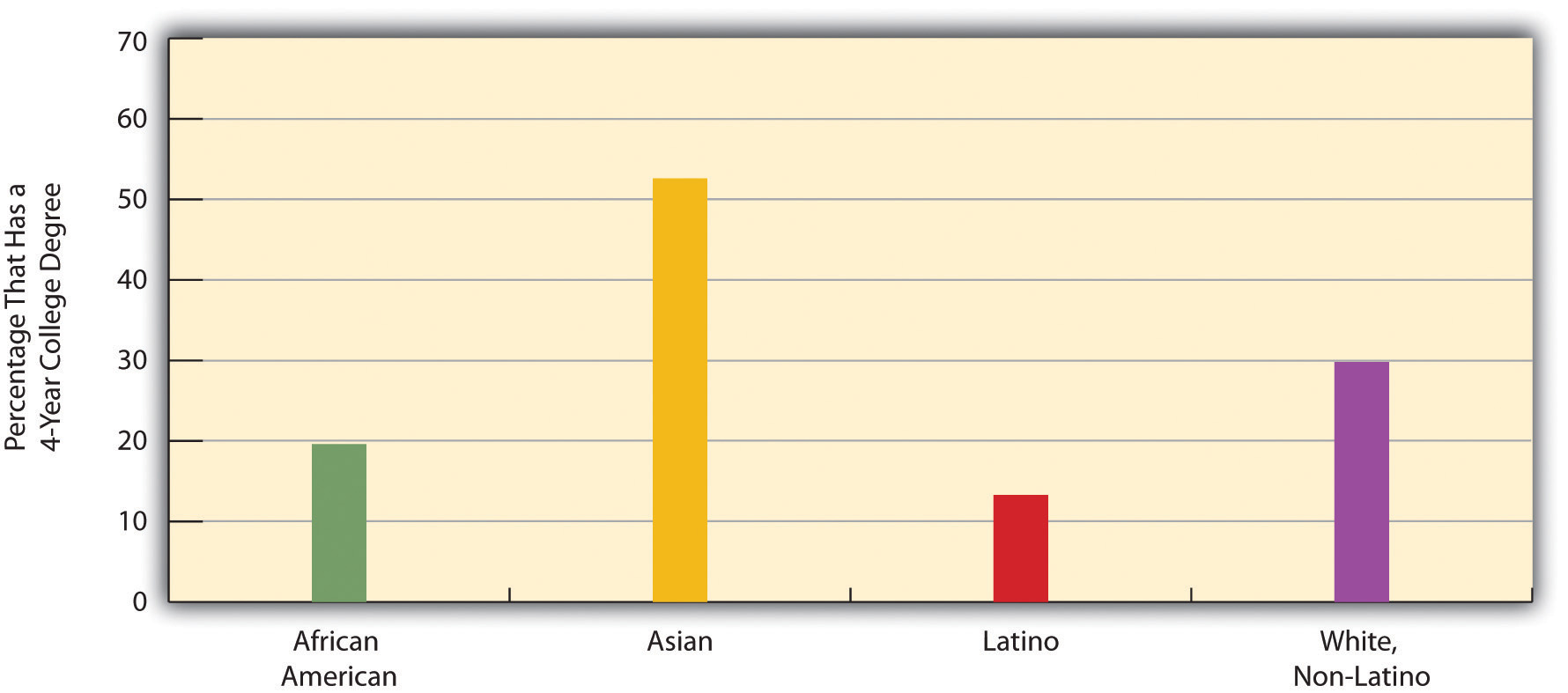

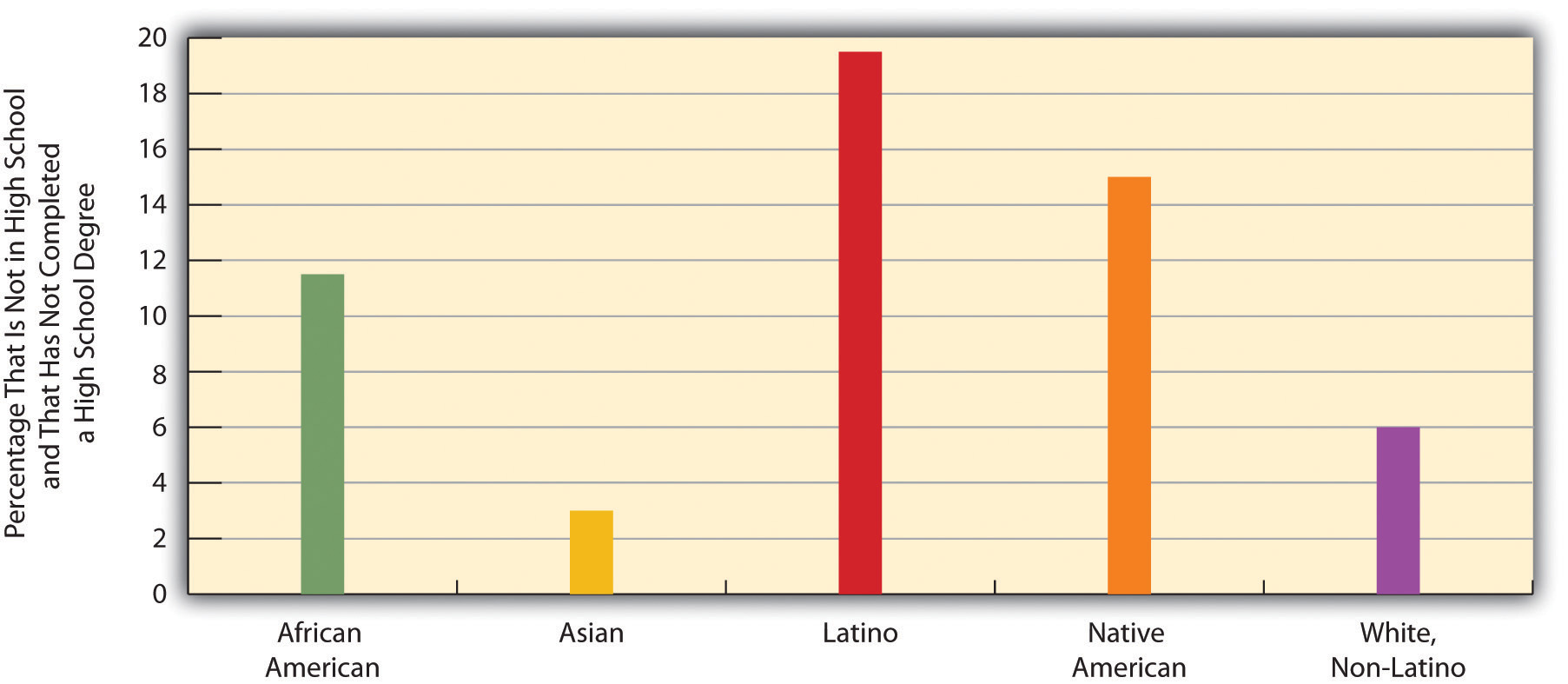

The figure below “Race, Ethnicity, and High School Dropout Rate, 16–24-Year-Olds, 2007” shows how race and ethnicity affect dropping out of high school. The dropout rate is highest for Latinos and Native Americans and lowest for Asians and whites. One way of illustrating how income and race/ethnicity affect the chances of achieving a college degree is to examine the percentage of high school graduates who enroll in college immediately following graduation. As the figure “Family Income and Percentage of High School Graduates Who Attend College Immediately After Graduation, 2007” shows, students from families in the highest income bracket are more likely than those in the lowest bracket to attend college. For race/ethnicity, it is useful to see the percentage of persons 25 or older who have at least a 4-year college degree. As the figure “Race, Ethnicity, and Percentage of Persons 25 or Older With a 4-Year College Degree, 2008” shows, this percentage varies significantly, with African Americans and Latinos least likely to have a degree.

Figure: Race, Ethnicity, and High School Dropout Rate, 16–24-Year-Olds, 2007

Figure: Family Income and Percentage of High School Graduates Who Attend College Immediately After Graduation, 2007

Figure: Race, Ethnicity, and Percentage of Persons 25 or Older With a 4-Year College Degree, 2008

Why do African Americans and Latinos have lower educational attainment? Two factors are commonly cited: (a) the underfunded and otherwise inadequate schools that children in both groups often attend and (b) the higher poverty of their families and lower education of their parents that often leave them ill-prepared for school even before they enter kindergarten (Ballantine & Hammack, 2009; Yeung & Pfeiffer, 2009).

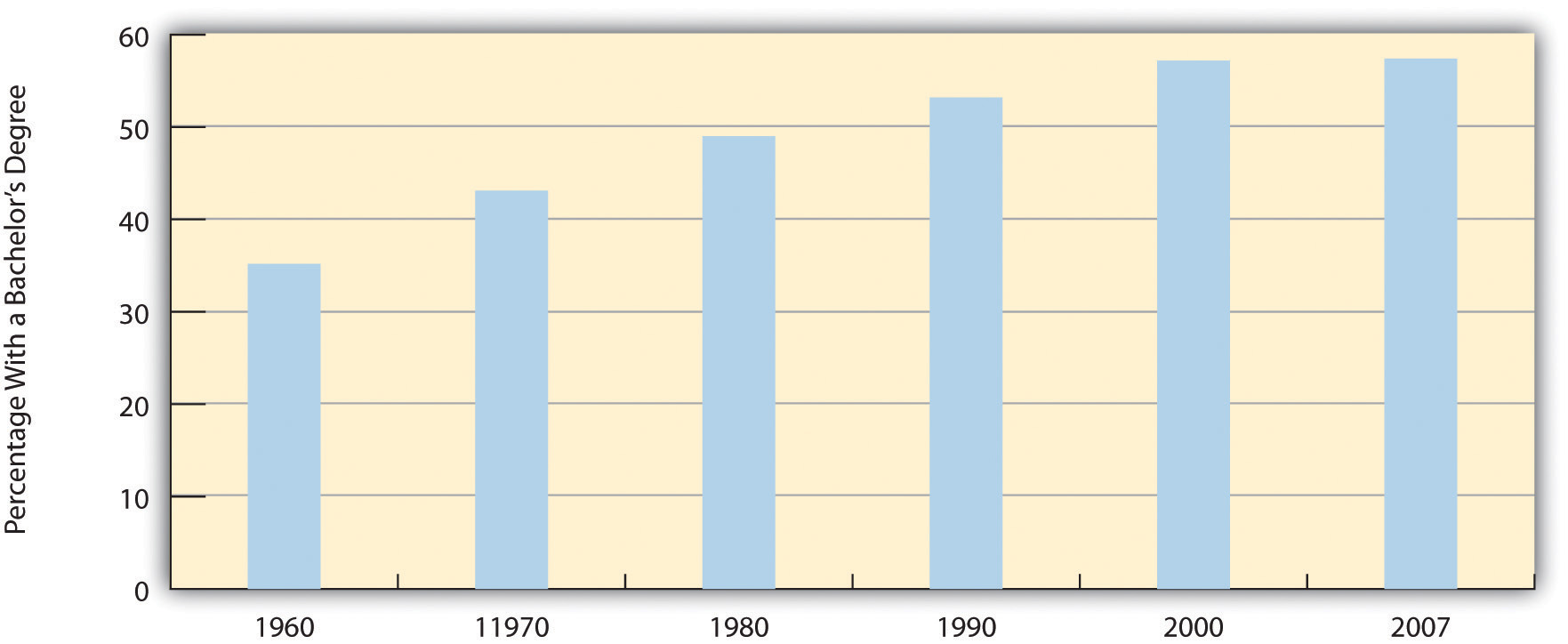

Does gender affect educational attainment? The answer is yes, but perhaps not in the way you expect. If we do not take age into account, slightly more men than women have a college degree: 30.1% of men and 28.8% of women. This difference reflects the fact that women were less likely than men in earlier generations to go to college. But now there is a gender difference in the other direction: women now earn more than 57% of all bachelor’s degrees, up from just 35% in 1960 (see the figure “Percentage of All Bachelor’s Degrees Received by Women, 1960–2007”.)

Figure: Percentage of All Bachelor’s Degrees Received by Women, 1960–2007

The Difference Education Makes: Income

Have you ever applied for a job that required a high school degree? Are you going to college in part because you realize you will need a college degree for a higher-paying job? As these questions imply, the United States is a credential society (Collins, 1979). This means at least two things. First, a high school or college degree (or beyond) indicates that a person has acquired the needed knowledge and skills for various jobs. Second, a degree at some level is a requirement for most jobs. As you know full well, a college degree today is a virtual requirement for a decent-paying job. Over the years the ante has been upped considerably, as in earlier generations a high school degree, if even that, was all that was needed, if only because so few people graduated from high school to begin with (see figure “Percentage of Population 25 or Older With at Least a High School Degree, 1910–2008”). With so many people graduating from high school today, a high school degree is not worth as much. Then, too, today’s technological and knowledge-based postindustrial society increasingly requires skills and knowledge that only a college education brings.

Figure: Percentage of Population 25 or Older With at Least a High School Degree, 1910–2008

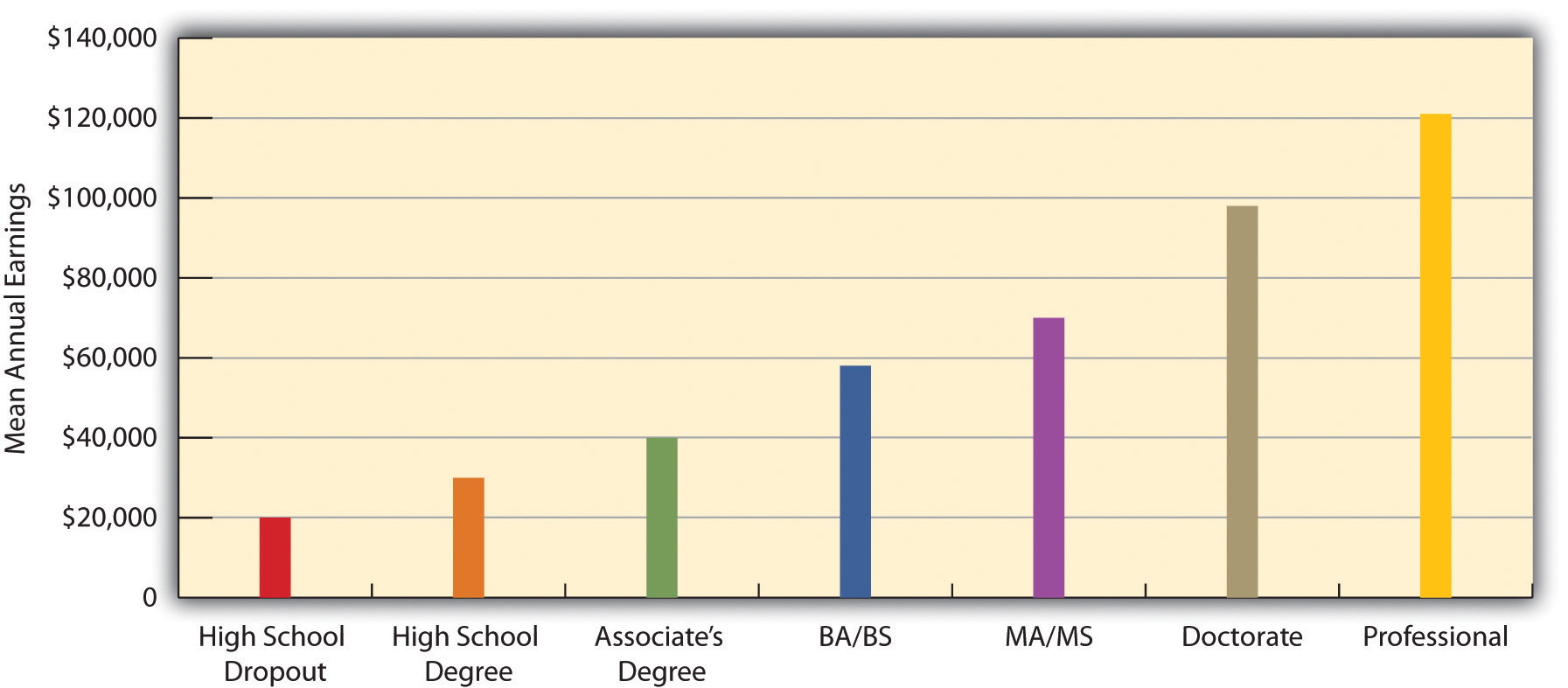

A credential society also means that people with more educational attainment achieve higher incomes. Annual earnings are indeed much higher for people with more education (see figure “Educational Attainment and Mean Annual Earnings, 2007”). As earlier chapters indicated, gender and race/ethnicity affect the payoff we get from our education, but education itself still makes a huge difference for our incomes.

On the average, college graduates have much higher annual earnings than high school graduates. How much does this consequence affect why you decided to go to college?

Figure: Educational Attainment and Mean Annual Earnings, 2007

The Difference Education Makes: Attitudes

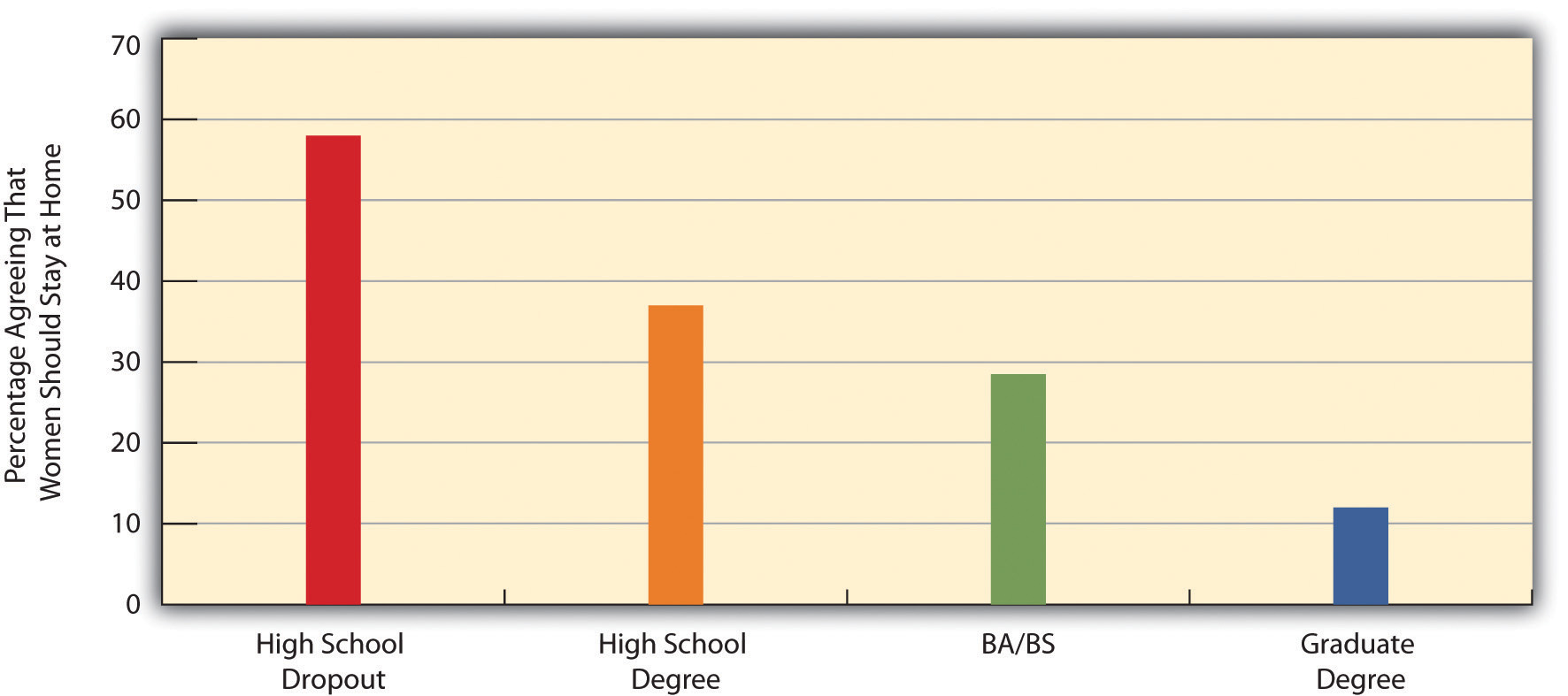

Education also makes a difference for our attitudes. Researchers use different strategies to determine this effect. They compare adults with different levels of education; they compare college seniors with first-year college students; and sometimes they even study a group of students when they begin college and again when they are about to graduate. However they do so, they typically find that education leads us to be more tolerant and even approving of nontraditional beliefs and behaviors and less likely to hold various kinds of prejudices (McClelland & Linnander, 2006; Moore & Ovadia, 2006). Racial prejudice and sexism, two types of belief explored in previous chapters, all reduce with education. Education has these effects because the material we learn in classes and the experiences we undergo with greater schooling all teach us new things and challenge traditional ways of thinking and acting.

We see evidence of education’s effect in figure “Education and Agreement That “It Is Much Better for Everyone Involved If the Man Is the Achiever Outside the Home and the Woman Takes Care of the Home and Family””, which depicts the relationship in the General Social Survey between education and agreement with the statement that “it is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.” College-educated respondents are much less likely than those without a high school degree to agree with this statement.

Figure: Education and Agreement That “It Is Much Better for Everyone Involved If the Man Is the Achiever Outside the Home and the Woman Takes Care of the Home and Family”

As two of our most important social institutions, the family and education arouse considerable and often heated debate over their status and prospects. Opponents in these debates all care passionately about families and/or schools but often take diametrically opposed views on the causes of these institutions’ problems and possible solutions to the issues they face. A sociological perspective on the family and education emphasizes the social inequalities that lie at the heart of many of these issues, and it stresses that these two institutions reinforce and contribute to social inequalities.

Accordingly, efforts to address family and education issues should include the following strategies and policies, some of which were included in the previous section on reducing social inequality: (a) increasing financial support, vocational training, and financial aid for schooling for women who wish to return to the labor force or to increase their wages; (b) establishing and strengthening early childhood visitation programs and nutrition and medical care assistance for poor women and their children; (c) reducing the poverty and gender inequality that underlie much family violence; (d) allowing for same-sex marriage; (e) strengthening efforts to help preserve marriage while proceeding cautiously or not at all for marriages that are highly contentious; (f) increasing funding so that schools can be smaller, better equipped, and in decent repair; and (g) strengthening antibullying programs and other efforts to reduce intimidation and violence within the schools.

10 WAYS SCHOOL HAS CHANGED…

The following is an excerpt from What She Said published AUGUST 5, 2016. It’s less than a year since I wrote lamenting the empty space in our new building, while teachers kept their doors shut and the learning inside their own rooms. Walking through ‘the space’ these days, as we approach the end of the school year, I’m struck by how much has changed.

There are groups of kids everywhere, sprawled on the floor, huddled on the steps, sitting around tables, even standing on chairs so that they can film from above! They are collaborating on inquiries, creating presentations, making movies and expressing their learning in all kinds of creative ways. It’s active and social, noisy and messy… as learning should be.

School has changed…

1. We used to imprison the learning inside the classrooms… Now the whole school is our learning environment.

2. We used to find information in books and on the internet… Now we also interact globally via Skype with primary sources.

3. We used to control everything… Now students take ownership of their learning.

4. We used to think ‘computer’ was a lesson in the lab… Now technology is an integral part of learning across the curriculum.

5. We used to collect students’ work, to read and mark it… Now they create content for an authentic global audience.

6. We used to strive for quiet in the classroom… Now the school is filled with vibrant and noisy engagement in learning.

7. We used to teach everything we wanted students to know… Now we know learning can take place through student centred inquiry.

8. We used to set tests to check mastery of a topic… Now learning is often assessed through what students create.

9. We used to plan differentiated tasks, depending on ability… Now digital tools provide opportunities for natural differentiation.

10. We used to have an award ceremony for the graduating Year 6 students… Now every child will be acknowledged at graduation.

Not every point is uniformly evident across the school irrespective of teacher, class and time (yet), but most are well on the way. Learning in our school has changed enormously… and is constantly changing. Is yours?

Candela Citations

- School building and recreation area in England. Authored by: Larkmead School. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/School#/media/File:Lmspic.png. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Introduction To Sociology 2E. Authored by: Candela Open Courses. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.candelalearning.com/sociology/chapter/introduction-to-education/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 10 WAYS SCHOOL HAS CHANGEDu2026. Authored by: What Ed Said. Located at: https://whatedsaid.wordpress.com/2011/12/13/10-ways-school-has-changed/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike